Anybody with a passing interest in country music over the last few years cannot have failed to notice the number of apparently new and successful Black country artists such as Breland, Valerie June, Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Allison Russell, and the UK’s own Yola and Lady Nade, who are adding a new dimension to the music. This success is reflected in the number of US radio shows focusing on Black country as well as an obligatory US documentary. The interesting thing with the emerging Black country artists is that they follow different traditions ranging from the Charley Pride approach of singing and playing in the current style of Nashville, Charley Pride may have been Black but he fully embraced the Nashville sound of the ‘60s and ‘70s becoming RCA’s best-selling artist since Elvis Presley, to the more folk roots of the music in bluegrass and old-time, as well as a more modern pop country soul approach.

Anybody with a passing interest in country music over the last few years cannot have failed to notice the number of apparently new and successful Black country artists such as Breland, Valerie June, Rhiannon Giddens, Amythyst Kiah, Allison Russell, and the UK’s own Yola and Lady Nade, who are adding a new dimension to the music. This success is reflected in the number of US radio shows focusing on Black country as well as an obligatory US documentary. The interesting thing with the emerging Black country artists is that they follow different traditions ranging from the Charley Pride approach of singing and playing in the current style of Nashville, Charley Pride may have been Black but he fully embraced the Nashville sound of the ‘60s and ‘70s becoming RCA’s best-selling artist since Elvis Presley, to the more folk roots of the music in bluegrass and old-time, as well as a more modern pop country soul approach.

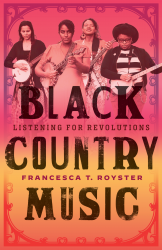

This makes Francesca T. Royster’s ‘Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions’ a timely entry into the debate surrounding what all this may mean, not only for country music but also for American society generally, and how Black people define themselves. While the official history of country music only shows three Black members of the Grand Old Opry, DeFord Bailey, Charlie Pride, and Darius Rucker ex of Hootie & the Blowfish, there is no doubt about the debt country music owes to Black musicians. While this history is important, ‘Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions’ is not really a history of Black country music, but an examination of what is driving the current movement and how it fits with the development of what is considered Black. Francesca Royster is a Black professor of English at DePaul University, and her interest in Black country music was piqued by her daughter’s and her daughter’s friend’s interest in the genre, though she has a deeper personal relationship with country music generally having spent part of her childhood in Nashville herself, and she is also informed by queer theory and Black feminist scholarship.

A surprising thing about ‘Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions’ is that given the potential complexity of the subject, it is only 248 pages, and this is due to the creative format that Francesca Royster has taken that weaves in her personal experience with country music and being Black in American with a context-setting brief history of Black musicians influence on country music in the Introduction, with the main part of the book examining it’s subject through the careers of six, sometimes surprising, artists namely Tina Turner, Darius Rucker, Beyoncé, Valarie June, Our Native Daughters, and Lil Nas X. I found the Introduction to be absolutely key to understanding Royster’s approach and position.

The Introduction starts with the author recounting her experiences at a community BBQ in Chicago which included live country music. Among the country fans with their hats and boots were some Black guests, and Royster recounts how those that she spoke to claimed to be there only for the food, and not the music. Royster then tells us she believes these responses were based on a self-protection impulse where it is not culturally acceptable for Blacks to enjoy country music. The introduction then gives a brief history of the Black influences on the genre starting with the blackface Minstrel Shows of the 1830s which marked the first time music popular was written down and thus made more widely available. She then describes how the rise of the Klan was responsible for the racist aspect associated with country music even today, and how the Jim Crow laws meant that the Black artists who did break through. such as DeFord Bailey, had to watch their behaviour and attitude. The Jim Crow influence extended beyond the repeal of the actual laws in 1965. She notes that while the country soul of the ‘60s showed Black and White musicians making music together, it was still White-controlled record labels and White music business executives that controlled the music and made most of the profit. She also argues that Black country is something apart from mainstream country, and likens it to the innovation of previous Black art forms.

While there may be a few eyebrows raised at a chapter on Tina Turner, we are reminded that her debut solo record was an album of country covers. As a member of The Opry Darius Rucker is an obvious choice, but Royster focuses on his bro-country status and his debt to Charlie Pride. The chapter on Beyoncé focuses on the performance of her single ‘Daddy Lessons’ at the 2016 Country Music Association Awards with the Chicks, which caused a conservative backlash. Discussing Valerie June, Royster homes in on her voice and its echoes of Elizabeth Cotton and Geeshie Wiley. The chapter on Our Native Daughters may not be surprising given the members of that group, but Royster wonders whether Black culture can reclaim the banjo as its voice in a musical form that is the epitome of White Supremacy. The final artist featured by Royster is Lil Naz X and his song ‘Old Town Road’ which examines the still racist nature of country music, exemplified by the fact that Billboard removed the song from the Country Top 100 because it wasn’t country enough and also as an example of Black musical innovation.

Concluding, Royster explains that she believes that Black country is just starting as a movement, and while to date it has largely featured artists fighting to get a seat at the country music table, Black artists will in the future use country to develop the Black identity. She notes the impact of Black Lives Matters on Black country, but questions how long-lasting this impact will be. She discusses artists she believes represent the future of Black country and looks forward to the day when it is acceptable for the Black community to just simply openly enjoy country music.

‘Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions’ is not a definitive work on Black country, how could it be at only 248 pages, but it is timely and does bring new ideas to what will be an ongoing debate both within country music and the Black community. Occasionally Royster’s text betrays her academic background but most of the time it is very readable, and it is also clear how heartfelt the arguments are. Given the wide-ranging issues and subject matter covered ‘Black Country Music: Listening for Revolutions’ may not be for every music fan interested in country music, but if you are interested in American history, if you want to gain a better understanding of some of the deep-seated tensions in current American society, and have a glimpse of how country music may develop, then you should read it. If you don’t agree with everything Francesca Royster says it doesn’t matter, the debate is what is important.