Books Editor, Rick Bayles, writes – When Gordon submitted this latest article for his ‘Paperback Riders’ series neither of us knew it would, sadly, be his last. It has been a genuine pleasure to work with Gordon since he first joined AUK; books meant a great deal to him and he quickly made himself a valuable member of the book review team. When he came up with the idea for ‘Paperback Riders’, we all thought it was a good one and very Gordon, but we weren’t entirely sure how the readership would take to it. We should’ve known that his uncompromising take on an eclectic mix of readings that had resonated with him, for a variety of reasons, would have great appeal to our readers, who also have strong opinions of their own. For me, ‘Paperback Riders’ is the essence of Gordon Sharpe as a writer. Clear, concise analysis of the writing, and the ideas behind the writing, as he saw them. A reflection of his enquiring mind and the joy he got from putting a piece of prose under the microscope and diving into it. As a writer, he never compromised his opinions but was always prepared to discuss them; he didn’t shy away from confrontation but he was always prepared to listen to another view. In many ways, this article is the perfect, if unexpected, way to bring down the curtain on this series. Taking on the writing of Robert Zimmerman is not for the faint-hearted, especially if you come to criticise, not praise him. As ever, Gordon states his position from the start and, while he doesn’t waiver from the path, writes with affection and humour, to acknowledge that, maybe, there is something to Dylan after all! It’s a great article and the perfect reflection of a man who’ll be much missed.

Dylan’s interesting and engaging account of his early years delivers a degree of focus and clarity not always apparent in his other work – and some of it may well be true.

In deference to many of my colleagues, who I know feel that Dylan is an exceptional artist, I decided to review his ‘Chronicles‘, – a book that on first reading I had enjoyed, somewhat to my surprise. Reading it the second time around has caused me to revise my opinion slightly but there are still parts, such as the description of New York City and the artistic scene when Dylan first arrives, that read very well indeed. My revised view is that it is rather too much of a hodgepodge to be wholly successful – but there is a lot that’s good.

In deference to many of my colleagues, who I know feel that Dylan is an exceptional artist, I decided to review his ‘Chronicles‘, – a book that on first reading I had enjoyed, somewhat to my surprise. Reading it the second time around has caused me to revise my opinion slightly but there are still parts, such as the description of New York City and the artistic scene when Dylan first arrives, that read very well indeed. My revised view is that it is rather too much of a hodgepodge to be wholly successful – but there is a lot that’s good.

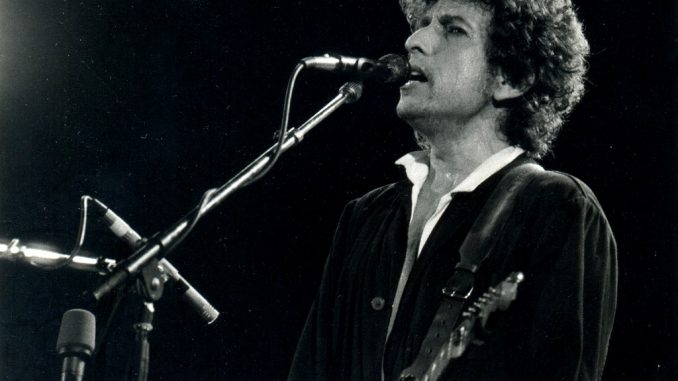

Let me state my position. Dylan has written some excellent songs and many are best heard when covered by other artists – which reminds us that he hasn’t got much of a singing voice. Musically much of his work brings together fine musicians and manages to make the end result unimpressive and repetitively dull. If anyone can point me toward a piece by Dylan wherein it can be said that it was beautiful then please go ahead – I’m well aware that I haven’t heard much of his extensive output so I’m happy to be educated. Whilst he can write and sing in a tender and affecting way – for example, ‘Lay Lady Lay’, – much of his output is dirge-like and lyrically akin to the first efforts of a bright sixth – former. ‘Si Tu Dois Partir‘ is somewhat removed from ‘If You’ve Got to Go, Go Now’, but goodness don’t the Fairports bring a bit of sparkle to it – and seem to have a laugh in doing so. Here’s a lyric from one of his most famous songs:

‘You used to ride on the chrome horse with your diplomat / Who carried on his shoulder a Siamese cat / Ain’t it hard when you discover that / He really wasn’t where it’s at / After he took from you everything he could steal’.

As one listener noted – ‘No idea where he comes up with this shit, but it’s brilliant’. Or in my view, it’s nonsense and the fourth line is just lazy, clumsy ’60s hip speak that looks hugely dated – like a rolling clunker.

Whilst Dylan is noted for what has been called his ‘sardonic wit’, I don’t find a great deal of humour in what he does, which leaves an impression of grimness that is hard to shake – though again I am happy to be enlightened. The hardcore end of his following is particularly alienating; ranging from those that believe he is the second coming to others that feel any lukewarm appreciation of the maestro is akin to a certifiable mental illness. In my view his own approach has done nothing to deflate these two views, despite his protestations that he is not the messiah, cloaking so much of what he does in an apparently quasi-mystical aura.

So what of Dylan the writer. Essentially it’s a mixed bag and if you check out the many comments on Goodreads (admirable for its range of generally well written and well thought out appreciations) then the picture becomes clear. Some find ‘Chronicles,’ poetic, others that it is rambling, poorly edited and often quite boring. There are those that feel he drops too many names whilst others praise his consistently positive references to his peers. Perhaps the biggest surprise is that there are some very pointed accusations of plagiarism. Whilst I have neither the time nor the inclination to explore them in any depth these claims seem well documented and I don’t see many comments to the contrary – rebuttals are more along the lines of ‘so what’. Notwithstanding the Led Zeppelin / Ed Sheeran / George Harrison examples plagiarism in music seems to be accepted within certain bounds and some of it is highly likely to be relatively unconscious (ok I might be being generous). Lifting passages wholesale from other writers is something different though. One thing that does surprise me a little is the number of alleged sources

‘Bob is not authentic at all,” Joni Mitchell told The Los Angeles Times in 2010, referring, of course, to Bob Dylan. “He’s a plagiarist, and his name and voice are fake. Everything about Bob is a deception’.

She did later clarify those comments –

‘I like a lot of Bob’s songs, though musically he’s not very gifted. He’s borrowed his voice from old hillbillies. He’s got a lot of borrowed things. He’s not a great guitar player. He’s invented a character to deliver his songs. Sometimes I wish that I could have that character — because you can do things with that character. It’s a mask of sorts’.

Initially slightly amusing but ultimately increasingly irritating the debate becomes a predictable back and forth with obvious sides being taken. It seems most are willing to concede that Dylan as with so many other writers is happy to borrow and we are left to judge – if we are aware of it happening – as to whether or not that is acceptable. A fair point is made about acknowledged and unacknowledged borrowings and the differences between allusion and plagiarism. I’d be lying if I didn’t acknowledge the feeling of disappointment when I realised that perhaps, in reading the book, I was not being privy to the author’s deepest thoughts but perhaps those of another. When I use the work and words of others in my own writing I hope I am clear in saying that they come from elsewhere.

I am amused and slightly puzzled that the awarding of a Nobel Prize has been seen as irrefutable proof of Dylan’s quality and Wikipedia provides a summary of some reactions – positive and negative – to that honour. Dylan’s response to the award seems to have been pretty churlish (actually in my world it’s called bloody rude) and if he so wished he could, like Jean-Paul Sartre, just have said no from the outset. It may be that he has given the $.932 million prize money to charity but as far as I am aware there is no public record of that. The question of plagiarism arises again from his acceptance speech, which seems to have been much aided by various additions from student crammer, ‘Spark Notes’. It makes you wonder if this is someone trying to prove to the world that he is clever – I am taken by the comment right at the end of this article about whether Dylan would have passed an assignment on the basis of his work.

And so to the matter in hand. The structure of the book is not always easy and I would agree with those who see it as a weakness – it’s almost 4 separate short stories. The book starts in the early 60s, then proceeds via 1970, 1989 and then back to 1959. In some ways, it’s not a problem but a little signposting would not go amiss, To an extent the more research I did the more I was not wholly sure about all those dates except those of the two albums. There again, once warned, I guess you can read it in any order you choose.

The first two chapters, ‘Marking up the Score’, and, ‘The Lost Land’, enter the world of Llewellyn Davis and I must admit I’m a sucker for that film and endlessly fascinated by the period and people depicted therein. I don’t find that there is too much name dropping, as some suggest, and see it more as reasonable scene setting as a cast of thousands (well, it’s only a turn of phrase) pass before our eyes – including Dave van Ronk as apparently portrayed by Oscar Isaac in the film. It’s not just the musicians though, as Dylan meets and gets his physique critiqued by Jack Dempsey. He starts to make up his own mythology – coming to town on a freight train – but does eventually tell the truth about where he came from how he got there and that he has really come to New York to find Woody Guthrie.

Dylan introduces us to a variety of legendary venues and the people who control them, Van Ronk for instance at the Gaslight whilst Fred Neil associates with Café Wha? He introduces us to Ray Gooch and Chloe Kiel with whom he lives for some time as he sofa surfed around New York – both seem more interesting than many of the musicians. He also has interesting pen portraits of Harry Belafonte and Mike Seeger. Not being the brawniest of men he often comments on the physicality of others. There is a tendency to mythologise the mundane but Dylan’s thoughts on music, culture and literature are all worth a read. Pleasingly he dismisses the negativity and pointlessness of Dean Moriarty / Neal Cassady and his endless journey to nowhere. This is unusual because rather than criticise people Dylan tends to talk about things and people that he doesn’t ‘understand’ rather than dislikes. As your grandmother would approvingly agree – ‘if you can’t say something nice…..’ He has time for Paul (Noel) Stookey of Peter, Paul and Mary who he paints as quite a singular individual – not the tall rather distantly ascetic character that the listener might have perceived. We learn later in the book that Stookey could do a mean impression of Dean Martin imitating Little Richard – if true then the mind boggles? Dylan has plenty of truck with what might be considered the commercial, popular end of the music of the time and already he was claiming that neither he nor Guthrie were protest singers. How does the saying go – ‘if it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck’? This denial of how the world saw, and continues to see him, runs throughout the book.

Dylan meets a lot of the jazzers of the time and when he tells Thelonius Monk that he is a folk singer the pithy and apposite reply is, ‘We all play folk music’, Personally I think, Thelonius my old friend, that you got it spot on and if we are talking musical genius then I know where my money lies.

I’d argue that these opening two chapters are the highlight of the book and the hustling, bustling freezing vitality of New York is excellently portrayed. Dylan never conceals the sense of his own impending success – even greatness – and I guess he wasn’t wrong.

The second section moves us to 1970 and the recording of, ‘New Morning‘, post ‘the motorcycle crash’ – and why there is such a mystery around that I’ve never understood. I’ll confess – I fell off mine twice. In this section, there is a meeting and possible project with the poet Archibald McCleish which never comes to fruition, and there’s a hint of something unpleasant when Dylan recounts how the play opened and closed within 2 days. Dylan talks of his wife and family though chooses not to name her (and which one is she?) which seems odd and we are introduced to a lengthy repudiation of his role as the, ‘voice of a generation. At first reading, this irritated me and people have their different ways of dealing with fame – some being very skilled at avoiding the limelight – others less so. To my mind, Dylan has often courted his own notoriety. Still, he claims to be ‘more a cow-puncher than a Pied Piper’ though I think it’s clear he certainly wasn’t a cow-puncher. I had more sympathy with his dislike of the glare of publicity when I re-read, ‘Chronicles’, though watching Scorsese’s, ‘No Direction Home‘, can only leave you wondering why Dylan tolerates the press conferences if he hates them so much. His endlessly gnomic answers to what are sometimes reasonable questions don’t really do him any favours. I did rather doubt his claim in the book that if an admirer fell off his roof that he, Dylan, would be taken to court? I did wonder given American perspectives on such things if that would be before or after the intruder was shot?

It’s clear though, that whilst living in Woodstock, he had little if any peace and he moved to NYC, finds little improvement, then headed west,

‘I had been anointed as the Big Bubba of Rebellion, High Priest of Protest, the Czar of Dissent, The Duke of Disobedience, Leader of the Freeloaders, Kaiser of Apostasy, Archbishop of Anarchy, the Big Cheese’.

The third chapter, ‘Oh Mercy‘, recounts the making of the album in New Orleans with Daniel Lanois – having been pointed in his direction by Bono. He is 18 months through a 3-year tour, concerned about his singing and sporting a hand injury that affects his guitar playing – which leads to a rather lengthy explanation of how he adjusted which is not so interesting and very possibly fabricated. There are many who believe much of this chapter is just made up – including biographer Clinton Heylin. Dylan is also suffering writer’s block, though seemingly it’s broken as he pens, ‘Political World’.

The studio process does not always go well and we get a good sense of that and of the city itself. Increasingly one realises that Dylan seems more gifted in terms of describing things, rather than ideas or states of mind. A perfect little vignette within this chapter is his outing to King Tuts Museum and his meeting with a character called Sun Pie. He’s interesting enough and the interlude reads well, but Dylan again over-eggs the pudding to the point where we might believe Mr Pie to be much much more than he actually is. Or is he another figment?

The recording process is fraught and Lanois and Dylan take some while to get on the same page – guitars were smashed apparently – but the general feeling was that this album was a return to form after a lacklustre run. It applies to many artists but I had to wonder if any of those rejected takes were eventually released to a grateful/gullible public? It was obvious at the time that for Dylan many were just not working. So presumably they would be best kept in the bin?

And then back to 1959 and, ‘River of Ice’, and the qualities of the opening pages – descriptions of things like a family rubber-gun fight and the impact that synthetic rubber had on their fun. Much of this section is about life in Duluth which he reminds us was a major seaport. He goes to Minneapolis and stays in a student house and we see the beginning of his infatuation with Woody Guthrie – something that he is called out for by Jack Elliot who was a contemporary and friend of the great man. We learn of his meetings with Joan Baez and Suze Rotolo, the latter introducing him to the world of art including Brecht and Weil and the song, ‘Pirate Jenny’. We meet John Hammond, Len Chandler, Carolyn Hester, Bruce Langhorne and Albert Grossman – never a man, in Grossman’s case, more aptly named according to Hammond. All of this is very much a case of life’s rich tapestry, with a real sense of possibility captured within the pages

‘Everything was in transition and I was standing in the gateway. Soon I’d step in heavy loaded, fully alive and revved up. Not quite yet, though’.

The folk music scene had been like a paradise that I had to leave, Like Adam had to leave the garden.

Celebrities and the not so celebrated queue up on the cover of my paperback copy to pronounce this as a book of the particular year – and I would not wish to argue. I certainly don’t deny the quality on display – or the way it describes a period in time that has always fascinated me. It answers some questions and poses others as I guess most autobiographies do. Whilst Dylan is the victim of self-made obfuscation and mystery, for which I have limited time, the sense of what it was like to become so famous so quickly comes across as does the way he felt hounded. It’s interesting that so many similar if not equal talents fell by the wayside or remained in the shadows and we learn that some were resolute in achieving relative anonymity – Fred Neil being a prime example. Of course, it may be even if they had wished it otherwise their renown would never have matched Dylan’s.

Finally, I’d just like to let it be known that in the interests of research I did listen to, ‘New Morning’, and, ‘Oh Mercy’, and the effect was minimal although the musical side of, ‘Oh Mercy’, is interesting – on an album described by some as the most un Dylan like he ever made. To show I am not a complete curmudgeon I have to admit that there are some tracks on, ‘Self Portrait’, that I like; ‘Copper Kettle’, and, ‘Days of 49’ for instance. I believe that’s not considered acceptable though?

After all that then – it’s a great read. It might need a pinch of salt or two, possibly a bushel, and it’s not strictly autobiography as we would normally know it – but as an imaginative chronicle of the times when perhaps life was more straightforward but interesting and fluid, it’s good value. The obvious question is – where’s volume 2?

This piece is very much like Gordon the man. It is heartfelt and written with passion, and while Gordon’s views are challenging they are based on his detailed research and honest opinions. You didn’t have to agree with Gordon to appreciate his passion and integrity, or enjoy his writing.