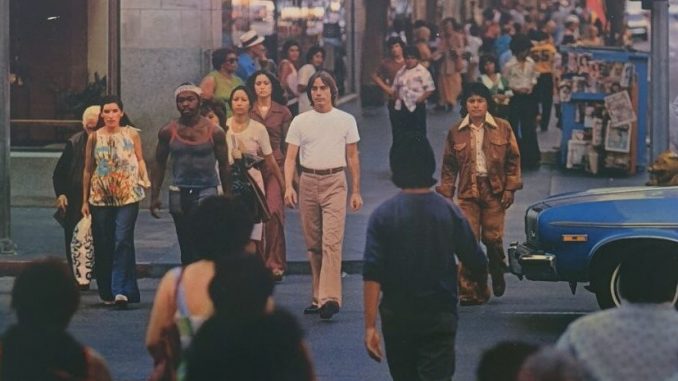

“Songwriting is a mysterious thing, sometimes it feels like consulting the oracle. As a songwriter you want to catch people while they’re dreaming. You want to find a way into their psyche when they don’t see you coming”. Well if anyone should know the true art of songwriting then surely it is Jackson Browne, who in 1965, aged just sixteen wrote his first great song, ‘These Days’ with a lyrical sagacity more commonly found in men at least twice his age. The following fifteen years would show him as a trailblazer for the confessional singer-songwriter genre, producing five of the finest albums of the seventies, most often compared against each other such is the rarified air they occupy that very few albums can draw comparison. Which of them is worthy of the greatest praise is a moot point as each in their own way capture a different stage in Browne’s musical and personal journey. In choosing ‘The Pretender’ I am well aware of the reverence in which its predecessors are held, but I hope that by revisiting the album I can convince you of its merit and position as possibly Browne’s crowning achievement.

“Songwriting is a mysterious thing, sometimes it feels like consulting the oracle. As a songwriter you want to catch people while they’re dreaming. You want to find a way into their psyche when they don’t see you coming”. Well if anyone should know the true art of songwriting then surely it is Jackson Browne, who in 1965, aged just sixteen wrote his first great song, ‘These Days’ with a lyrical sagacity more commonly found in men at least twice his age. The following fifteen years would show him as a trailblazer for the confessional singer-songwriter genre, producing five of the finest albums of the seventies, most often compared against each other such is the rarified air they occupy that very few albums can draw comparison. Which of them is worthy of the greatest praise is a moot point as each in their own way capture a different stage in Browne’s musical and personal journey. In choosing ‘The Pretender’ I am well aware of the reverence in which its predecessors are held, but I hope that by revisiting the album I can convince you of its merit and position as possibly Browne’s crowning achievement.

By 1975 Browne’s star was truly in the ascendancy, his latest album ‘Late For The Sky’ was both a favourite with the critics and his most commercially successful to date. However his personal life was in turmoil as his marriage to Phyllis Major, mother to his son Ethan born the previous year, was falling apart of which lyrical clues adorned many of the songs from the album. Towards the end of that year his time was split between writing material for his next album and working as producer on the eponymous album for his good friend Warren Zevon. Tragically by the March 1976 everything was to change as the news broke that Major had taken her own life. Now Jackson always claims that the bulk of the material for the new album which would become ‘The Pretender’ was written before his wife’s untimely death. However, the fact that the album would not be released until November of that year and that the subject matter of the songs were clearly thematically linked by death and parenthood one can conclude that Browne more likely and understandably wanted to deflect the focus from his own personal trauma. True, the delay could also be attributed to the decision to employ a real producer, the benefit of which may have become more apparent to Browne whilst taking the role for Zevon. In choosing Jon Landau, fresh from his success with Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born To Run’ it allowed Browne to concentrate purely on the writing while Landau brought a broader mix of musical styles and tempos to the overall sound.

The album opens with ‘The Fuse’ and finds Browne stepping back from the precipice on which he felt most comfortable and where he had previously delved so deeply into life’s abyss on his first three albums. His lyrical prose had constantly been laced with an impending doom whilst never losing confidence that love and romance would always catch his fall. But no longer. Love had betrayed him and the safety that its walls and towers had offered were nothing more than rubble at his feet. He was now in search of escape from this emotional turmoil as he sings “Forget what life used to be” questioning all he had valued and the futility of their importance as he comes to terms with the inevitable erosion of time. Yes he was wounded, yes he was bleeding, but he was not beaten. Listen closely, the defiance is there “I want to say right now I’m going to be around”. Musically the track opens with the gentle tap on the cymbals from Russ Kunkel while Craig Doerge offers some distant minor chords on the piano inviting Browne’s opening lines “It’s coming from so far away”. Whether he’s referring to the music or some spiritual connection matters not, and as the pace increases and the invaluable David Lindley weaves his magical slide guitar around the melody the listener is swept up and wrapped in the impending emotional uncertainty.

Track two ‘Your Bright Baby Blues’ finds Browne taking time out, contemplating the madness of the rat race and the yearn for that which can feel so close yet still be so far away. Is he looking for redemption or just release from the pain, from the guilt? Whichever, what stands out is the performance of his voice. Browne’s once hesitant singing had gradually improved with each album but here it soars with an emotionally charged sense of freedom and along with E Street Band stalwart Roy Bittan on piano and Lowell George’s fire-spitting slide guitar the song bristles with an energy not previously found on his earlier albums. The imagery may still be apocalyptic and the feeling of mortality more profound and raw but the juxtaposition of the accompaniment creates a conduit capable of traversing the foreboding troubled waters ahead.

The musical arrangement for the following track ‘Linda Paloma’ has always been a major talking point as here Arthur Gerst’s harp playing dominates, cascading around Browne’s vocals with only the subtle touch of Roberto Gutierrez violin adding any variation. Lyrically the song still finds Browne wrestling with his conscious in the shadows, raging at the unfairness that “love will fill your eyes with the sight of a world you can’t hope to keep”, which at first seems to lie at odds with the bright uptempo accompaniment which some felt undercut the lyrical message. However on closer listening you can sense the pending dawn starting to soften the darkness, and though Browne still struggles with his now cynical view of love still he sings to his “Mexican dove, the morning brings strength to your restless wings” it offers hope of a brighter day that the musical setting and overall sound tries to support.

Like most performers that transcend their genre, Browne often suffered from being seen as a symbol for everything it stood for rather than purely as an artist. There was a sense of responsibility to stylistically maintain and fulfil an unspoken promise. Bringing Landau onboard and relieving himself of the production responsibilities that he himself had tended to approach with a languid naivety was a deliberate attempt to create a sense of contrast and greater depth to the overall sound than he had previously been able to deliver. This inevitably garnered critical derision suggesting the songs and their subject matter were less effective in this more contemporary rock setting. Landau used more than thirty musicians during the recording but seldom has such quality been assembled nor perfection been delivered, never playing a note too many but making every note count. In truth I would suggest that it is Landau’s production along with the albums emotional impact that help makes ‘The Pretender’ Browne’s most rewarding.

Track four ‘Here Come Those Tears Again’ became the first single taken from the album and would reach number 23 in the Billboard chart. This song was co-written with Nancy Farnsworth, mother of Phyllis Major and is unsurprisingly the song that speaks directly to Browne’s late wife. It’s a song of shared grief and dealing with the recurring memories that haunt every waking day, yet despite the emotionally charged honesty that endures there is, as needs to be, a sense of self preservation as Browne concedes in the final line “I’m going back inside and turning out the light. And I’ll be in the dark but you’ll be out of sight”. Here again the accompanying uptempo arrangement with its infectious chorus feels at first at odds with the lyrical refrain but Browne’s vocals beautifully supported by Rosemary Butler and Bonnie Raitt quickly transcend any initial concerns.

‘The Only Child’ starts what would have been side two of the album in its original vinyl form and one can surmise that this song, at least, was probably written before Major’s suicide. Here we find Browne addressing his son Ethan, by now in his second year, trying to impart some fatherly advice that would be far beyond the comprehension of one so young and is probably more reflective of his own childhood as he struggles with the ultimate parental dilemma of letting go of being someone’s son and face the responsibility of being someone’s father, perceiving each as both a joy and a trap. Ably supported by such stellar musicians as Bill Payne on piano, Albert Lee on guitar as well as the ever reliable Lindley this time on violin and with harmony vocals supplied by Don Henley and J. D. Souther this track finds Browne moving on from his grief and starting to address his responsibilities however unsure and unprepared he feels. It may well be those insecurities that brought him to the next song ‘Daddy’s Tune’ where he turns to his father, long since alienated, for advice, maybe forgiveness, or simply redemption, its difficult to be sure though you do get sense of the shadow that Browne’s father held over his son. He had been a journalist for the U.S. Army Newspaper ‘The Stars and Stripes’ but was also a fine musician who had performed on stage with the legendary jazz guitarist Django Reinhardt as well as recording with Mahalia Jackson and Jack Teagarden and one can’t help but feel the immense footsteps in which Browne was expected to follow in. Nothing sums this tension up better than the lines to the final verse “Somewhere something went wrong, or maybe we forgot the song. Make room for my forty-fives along beside your seventy-eights. Nothing survives”. Structurally the song again delivers a variety of pathos and pace starting with a plaintive piano supporting Browne’s reflective tone before a horn section and Lindley’s trademark slide guitar transforms the track to a joyous anthem. What exactly is being celebrated is uncertain, but possibly this is Browne finally finding the courage to stand up to his father, braking free from his role as the subordinate son.

By the time we get to track seven, the penultimate song ‘Sleeps Dark And Silent Gate’ we gain a sense of the direction the album has subtlety been shepherding us towards. Browne’s out pouring of grief for his wife’s passing has reached a pivotal point with the acceptance that there is no going back or even standing still, only forward and letting go. No contemporary male singer songwriter had previously dealt so honestly and deeply with the vulnerability of romantic idealism and the power of love. Now he had to deal with loss, pain and finality as he adjusts from being the narcissistic youth to the battle scarred young adult. Is the title a metaphor for death or simply the safe haven of the deepest sleep where dreams cannot be recalled? Possibly both, for both require an acceptance of the irrevocable.

The final number is the title track, but rather than bringing everything to an obvious conclusion it instead offers a new beginning, a rebirth, for Browne is no longer the same artist that opened the album. Gone is that naïve romantic desperately clinging to the past, no more will he stand on the precipice of the abyss believing love will break his fall. In its place there is at first a faint sense of cynicism, though this is merely to fill the void while he regains his trust in the frailties of romance. He still can’t help himself from looking back and wondering whether it was all a dream but the poets soul has survived and any suggestion of a passive surrender are quashed. In proudly boasting “I’m going to be a happy idiot and struggle for the legal tender” he is not taking a sarcastic swipe at the onset of the ‘Yuppie’ though he prophetically predicts its coming by several years, but is simply reassessing his own place and role in society and establishing his new found values. Still caught between two worlds he will eventually step “Out into the cool of the night” because “he knows that all his hopes and dreams begin and end there”. The structural feel here is anthemic as it gently builds from Doerge’s piano, Fred Tackett’s guitar and sublime bass from Bob Glaub, to a rousing finale of strings and lush harmonies provided by David Crosby and Graham Nash. It is a celebration, paying homage to that which has been lost, but also to what has survived and the promise of the new.

Together Browne and Landau had created one of the benchmark albums of seventies American rock, reaching number 5 in the Billboard Top 200, paying homage to blue collared values, and merging it with a poetic vision to make a quintessential statement. In many ways ‘The Pretender’ is the culmination of everything Browne had done before, an introspective narrative of his life up to that time where no word is wasted as he’s forced to confront the romantic naivety that he held so dear with the harsh realties of grown up life. Everything he’d ever written was destined to finish here, this album, this track. Of course he would continue to write great songs, ‘Running On Empty’ had many, but his writing was changing, his focus was now shifting towards politics and environmental issues, the love songs would no longer reveal the same level of vulnerability. ‘The Pretender’ marked both the pinnacle of his artistic zenith and the beginning of the end to the confessional singer-songwriter. The seventies were coming to an end, and with it a wind of change would blow through the established musical hierarchy that few would navigate with the same confident grace.

So if ‘The Pretender’ is new to you, or if it managed to pass you by, failed to connect first time round or you’ve just forgotten its power, then allow this album, which Rolling Stone magazine rightfully included in their ‘Top 500 Albums Of All Time’, to enrich your world. In the forty-seven years since this album came into my life I have constantly reassessed what I perceived to lie at its heart, and only now in my sixties do I think I fully understand, as within these eight songs life’s journey is so eloquently laid out. I guess you just have to travel the road to truly appreciate the message, and yet Browne was still only in his late twenties when ‘The Pretender’ was released. That in itself should not be surprising when you remember at just sixteen years old he had the wisdom beyond his years to write “Don’t confront me with my failures I had not forgotten them”.

What a beautifully written piece. Chapeau bas.

Many thanks Angus, glad you enjoyed it.

Yes a fine piece indeed, thank you.

Of all of JB’s great albums, and there are many, this is the peak for me. The balance between music and lyrics is perfect as are the performances. From the album’s release to this day ‘The Fuse’ and ‘The Pretender’ ring with a truth that still makes my spine tingle and with the exception of ‘Linda Paloma’ (which I can do without) the other tracks are not far behind.

Just another “happy idiot”.

Thank you Nigel, glad you enjoyed the article and share my view with its place in Browne’s cannon of work. Do you think that the problem with ‘Linda Paloma’ is the arrangement, the lyrics or both?

It’s the arrangement that turns me off.

Yeah, and time certainly hasn’t been kind. It sounds dated unlike the rest of the album.

Thanks for all the interesting info about this great album. I remember going into the record shop to buy Running on Empty and guy in the shop recommending I buy the Pretender instead. I ignored his advice, but I did buy it soon afterwards. I completely disagree about Linda Paloma. It still sounds great to me with its timeless mariachi-style arrangement. It’s the interplay between the harp and the bass (probably a guitarron) that is the key.

Hi Pete. You’re right, Roberto Gutierrez did also supply the guitarron as well as the violin on this track and I’m pleased you’ve shouted up for the arrangement on ‘Linda Paloma’. In the article I’d tried to highlight the pros and cons for the track which, whatever your view, has always had a level of controversy about it with critics and fans alike from day one. What is great, is that in revisiting these albums in our ‘Classic Americana Albums’,feature it gives us not only the chance to bring the album to possibly a new audience but also to discuss the finer points of the album with long time fans like yourself. So many thanks for your in put and I hope you continue you enjoy the albums we revisit in this feature.

Hi Graeme. Along with Gram and Gene, Jackson was the mainstay of my musical enlightenment thro’out the 70’s. I don’t need to rehash all the plaudits already given here and in the scores of articles over the years, other than to add my own plaudit to you for an excellent article. With regard to Linda Paloma, I’m with Pete Feldon for exactly the same reasons. Lovely track. (Trivia … the only other track in the rock/roots/americana genre I can think of that employs a harp is Chris Isaak’s “I lose my Heart” (Mr Lucky)… ???) Oh, and just to finish, there are 2 or 3 occasions within your article where you ALMOST got me to agree with your assessment. However, “Late For The Sky” is the album that cannot be bested!!

Hi Alan. Thank you for getting in touch, your kind words, and sharing your view on this album. Chris Isaak’s track is a great shout which I must go back and listen too. If I managed on three separate occasions to almost sway you from “Late For The Sky” then I’ll settle for that, as you are clearly someone with great musical taste, and I hope you continue to enjoy the albums we revisit in this feature.

Don’t understand why this album hasn’t been Re-issued in Hi-Def format yet.

Totally agree.

The name of Jackson Browne’s son is Ethan, not Nathan. Good article about The Pretender.

Hi Treasa. Thanks for getting in touch, and thank you for pointing out the error. I had spelt Ethan’s name correctly earlier in the article, so I can only apologise for what was either an unnoticed typo or that damn predictive text. Anyhow, I will go back and correct it immediately. Thank you again for the heads-up, and glad you enjoyed the article.