In the second part of this new series for Americana UK, artists from across the genre discuss their approach to song-writing. As part of his between-song patter in his concerts, the late, great Americana singer-songwriter Guy Clark would sometimes preface his version of the Townes Van Zandt classic ‘If I Needed You’ with his tale of how he first heard it. It turns out that one morning of 1972 when Van Zandt was living with Clark and his wife Susanna, their guest rolled into the kitchen for some coffee, picked up his guitar and started playing the song.

Clark’s reaction: Great song, where did that come from?

TVZ: I wrote it last night in my sleep…rolled over, wrote it down, turned over and went back to sleep.

As for how he reacted to Van Zandt’s explanation, on the 2011 ‘Songs&Stories’ live album at least, Clark doesn’t open up much, just finishing his tale with a rather explosive “Humph!” and the somewhat cryptic comment “Suspicion Confirmed”. That last could be indicative of dumbfounded admiration at Van Zandt’s creative methodology, or maybe just good old-fashioned bafflement – even 40 years on.

Either way, for Karen Pittelman, the New York Americana and country singer-songwriter who leads the Karen And The Sorrows band, Van Zandt’s explanation wouldn’t have been so mystifying. After all, she, too, first crosses paths with a lot of her songs while she’s sleeping.

“I hear the music in a dream and it sort of wakes me up,” Pittelman, who now has three albums and an EP in her back catalogue, says. “You kind of hook something and try to reel it to the surface. Then I will half-wake up and sing whatever I was hearing into my phone.”

Hearing songs, or parts of them, for the first time in dreams is far from uncommon: the best-known case is probably Paul McCartney and ‘Yesterday’, but Jimi Hendrix and ‘Purple Haze’ (though whether Hendrix actually was or wasn’t asleep also seemingly depended on the interview he gave) Johnny Cash and ‘The Man Comes Around’, Elvis Costello’s ‘Honey Are You Straight or Are You Blind?’ are all on that list, too. (Costello apparently had no guitar in his house when he woke up in the middle of the night with that song ringing in his ears, so he slapped his hands on his kitchen counter while taping the lyrics to give it some kind of accompaniment. As for Johnny Cash, he famously said that while on tour in the UK, he had dreamed Queen Elizabeth II appeared and told him he was “like a thornbush in a whirlwind”, a line from the Bible that Cash then used in ‘The Man Comes Around’. You can’t help wondering what Guy Clark would have made of that!)

Anyway, what is notably different about Pittelman’s dreaming up songs is that it isn’t, like all of the above, a one-off or two-off experience. ‘Catching’ songs when asleep – or sometimes half-asleep – is her most common way of writing them.

Also a writing coach, Pittelman is the first to recognise that when it comes to getting something down on a page, her creative process is just one of many options. As she puts it, “we all have such different ways of getting there.” In her case, it so happens that musically she’s most productive when she has no conscious control over her thought processes, and she argues that that lack of control, interestingly, is precisely makes one of her songs a song, rather than, say, a poem.

“In other genres, I decide what I want to say and I write it. Even with poetry, what comes first is an image or phrase and I will then try to hone that,” she points out.

“But usually songs, when they come to me they have their own ideas, and I can’t fight that.”

“Sometimes I’ll dream it or sometimes I’ll be in a spaced out state and I’ll hear the music coming through. It’s sort of like when you’re changing channels on the radio and you sort of hear something coming through, and I’ll be, like ‘Wait, what’s that? Is that a song?’ It’s like it’s coming from a cosmic radio station in the sky.”

Being able to ‘tune in’ to that cosmic radio station, she argues, is by no means an exceptional gift for a privileged artistic elite. Rather “so much of being an artist is training yourself to notice when that little spark comes and not ignore it no matter what is happening.”

“There’s training yourself in that attentiveness and then there’s training yourself in craft.” Once that kernel of an idea shows up, Pittelman keeps “obsessively” singing the newly formed melody or rhythm to herself, working out a basic chord structure on her guitar as she starts the ‘craft’ part of the song-writing.

“That involves a lot of really long walks, and I wait for the song to tell me what it wants to be about,” she says, before adding, with a wry laugh, that “A lot of it is me wandering around Brooklyn singing to myself so I’m sure people think I’m really weird.”

However strange it may look from the passerby’ point of view, at that point in the process what Pittelman’s essentially aiming for, she says, are “Some lyrics that fit with the rhythm that the song wants to have. Then I start really obsessively honing the lyrics because they are really important to me, and I want them to be sharp and mean something.”

“Specially in country music, I think what makes it great are the lyrics, capturing a commonplace experience in a turn of phrase that you can really sink your teeth into. The ideal is that the music and the words are so intertwined you can’t even see the words without hearing the music to them.”

Travel is often cited as a source of inspiration for musicians. But as a “home body”, as she describes herself, having a fixed daily routine where she lives New York best kickstarts her creative processes – plus, often, repetitive physical exercise.

“I think there’s something to do with walking, maybe the fact that it’s rhythmic” – she says swimming laps of a pool also is very effective – “helps me get into that zone.”

If doing lengths of swimming pools and trudging the streets of Brooklyn sounds, as Pittelman admits, “very boring,” and the cosmic radio station concept sounds a shade zany, Pittelmann once again insists that each songwriter has their own, very individual approach – or variety of them. But in any case, the last part of the song’s journey to becoming a reality is similar all over.

“When I have that got through that phase I’ll make a little demo of it and depending what kind of configuration of the band I’ve got at the time, bring in other musicians. That’s my main process,” she concludes.

Getting the song to that point successfully though also depends heavily on musical craftsmanship, or as Pittelman puts it “The initial part of songwriting is maybe a bit mystical but the work that follows is not mystical at all.”

Rather it involves understanding “what structures are possible, when you need to follow the rules, when you should bend them, when you should break them. It requires tons of training and listening and thinking about how things are made and why they work on us the way they do.” Again, though, this isn’t some kind of exclusive academic club: much of her basic education in music as a child, she says, consisted of “obsessing with pop.”

“If you want to write you should obsessively listen to as much music as you can, but especially music you love and figure out what it is that the song does that makes you love it. Because the difference between a writer or critic and a listener is that when you are listening you don’t have to figure out why music does whatever it does for you. But as a writer or critic, you do.”

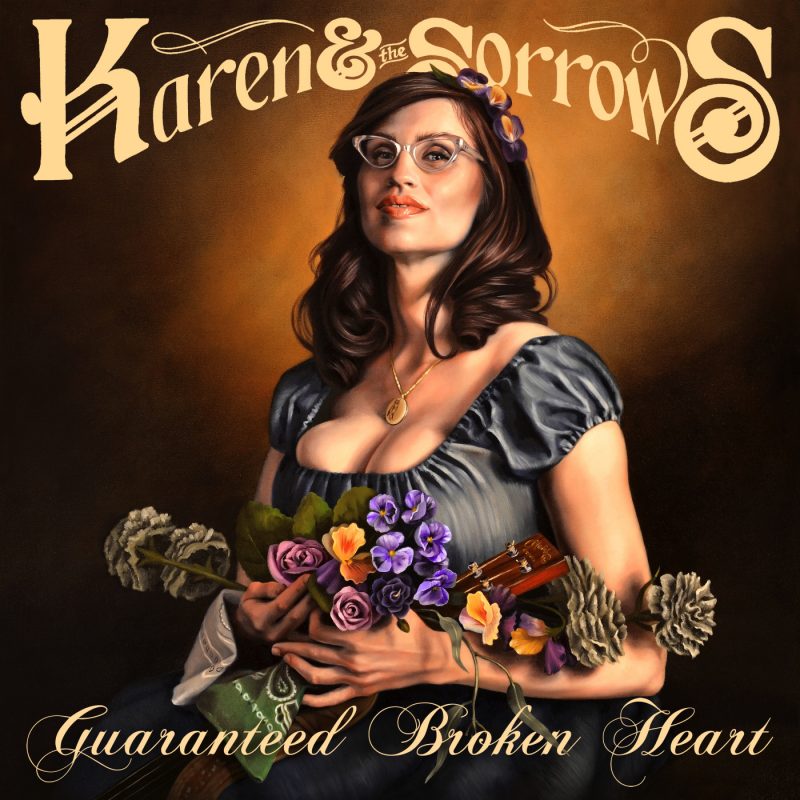

As for how her attitude to songwriting has changed over the years, it’s noticeable that her latest album, ‘Guaranteed Broken Heart’ (Ocean Born Mary Music, 2019), has a lot more connections with classical electric country, particularly the 1990s variety, than her previous work . And that, she says, is also to do with the way she’s now composing.

“The older I get, I get more like it isn’t about trying to make something new, or having to break the rules,” Pittelman said. “It’s about trying to understand the genre I’m working with and why have people come up with these particular conventions and how can I harness them to make the sound and tell the story I want to tell.”

She argues that this process of simplification to create greater power in songs is something Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen all did or do in their later years. By way of a specific example, she cites the straightforwardness and profundity of one of Cohen’s lines from ‘Anthem ‘(1982) – “there is a crack in everything, that’s where the light gets in” – compared to the much more complex imagery in the music of his youth in 1960s songs like Suzanne.

‘Guaranteed Broken Heart’ already marked a very different approach in other ways, given she and her long-standing band had split up, and that gave her independent-minded songs a greater opportunity to be themselves, she says. And to let her know about it, too.

“My songs don’t just tell me what they want to be about, they also have very particular ideas about how they want to be played. In the past I would be like ‘shut up, shut up’ ‘cos I have to bring the songs to the band to decide on their instrumentation. But for this album I was like ‘ok, tell me everything you want, I can’t promise you I’ll be able to get it but I’ll try.’”

“So a song like ‘Why Won’t You Come Back To Me?’ – that was stubborn and I kept trying to play it with an electric band. And that song was like ‘Fuck you, no! Get me a bluegrass band.’”

Her belief that the music is already created doesn’t just form the bedrock of her song-writing strategies, either. It’s also discernable in elements in her political and socio-cultural activism, both in the Queer Country movement and, more recently, in her forming the Country Music Against White Supremacy group.

Asked about the connection between her anti-white supremacy beliefs – she has written a lengthy, powerful essay about the subject, published on her band website and there is also a #ChangeCountry pledge link on there – and her composing songs, Pittelman says “I believe music chooses you, and it feels like it’s a sin against it, if everybody whom that music comes through can’t bring it into the world”.

“There are all these ways the country and Americana industries have made it from unwelcome to impossible for black musicians and other people of colour to do that. And I feel like we have an obligation as musicians to make sure there is the space and the resources and the welcome for anybody whom our music chooses.”

Within that context, Pittelman’s music writing is arguably both a creative activity and an activist’s tool as well, making a political statement. But in a way, the decision to go with country was, she says out of her hands.

“Initially I never had any intention of writing country songs or making country music and I certainly didn’t see anybody like me in that field, or any place for me given my own identity”, she recalls.

“But then I went through this very intense breakup with my partner of 15 years and all of a sudden all I could do was write country songs. I realised that all my life I’d been obsessed with pedal steel and if I went back and looked at a lot of the pop or rock songs I loved there were ones that had some secret pedal steel in it, like Joni Mitchell’s ‘California’.”

Formerly in a punk band, she says “ that was more for fun and I was thinking of my life as a non-fiction or a poet. I didn’t write the music for it, I just sang and we would just make up silly lyrics.”

“Then all of a sudden it hit me like a ton of bricks I had to break up with that band and I had to start finding new people. I had to deal with the fact I couldn’t stop writing country songs.”

The number of people out there who are capable of creating the bulk of a catalogue of songs whilst in an unconscious or semi-conscious state is probably extremely low, even if Pittelman’s dreaming up songs is really about the kernels of musical ideas, and it’s only through hard work – and a lot of walking around Brooklyn freaking a few people out – that they are completed as a playable reality.

Still, for her, sleeping is where it starts, or at least, where she believes the artist’s initial connection starts. “We all get creative impulses, but we tend to overlook them: you just need to learn to pay attention to them,” she concludes.

“Songwriters are people who know how to open their brains to the music coming through. But it doesn’t belong to us. All music is already out there.”

I have written a couple of songs myself in my sleep (The Paris Wife and Her Soldier Boy – the latter song a complete verse and chorus – Occasionally though when you play a recording back from waking up it sounds incomprehensible in the cold light of day lol

It’s great that you managed to show such creativity and bring the idea to life. Unfortunately, I cannot write songs, because in the evening I like them, and in the morning I delete all the recordings and leave them only in my memory.

it is so great

I’m constantly searching on the internet for posts that will help me. Too much is clearly to learn about this. I believe you created good quality items in Functions also. Keep working, congrats!