How a borrowed PA, off-brand guitars and a real piano created a new old sound.

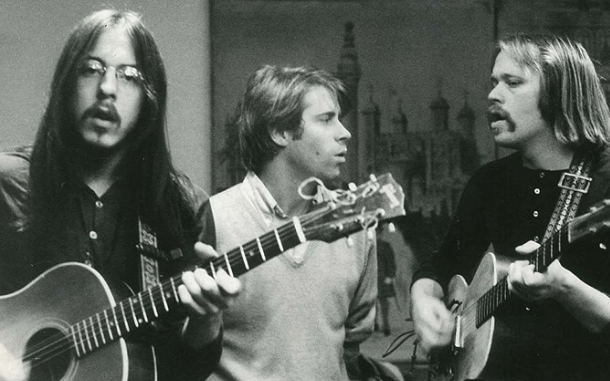

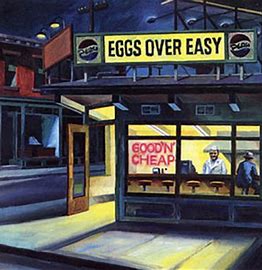

Normally, Americana UK interviews artists who are promoting an album, either of new material or a career retrospective, and in pre-COVID days, they may have been a tour lined up that also needed some promotion, and, depending on how things develop, hopefully touring will gradually become the norm again. This interview is different and is a mixture of music history and an early hint of new music from a member of one of the most influential bands of the last 50 years, who also hasn’t released any music since 1981. Martin Johnson wrote an article on iconic band Eggs Over Easy for Americana UK which was a celebration of a band that laid the foundations for pub rock and everything that flowed from that in ‘70s Britain. Jack O’Hara, guitarist, singer and songwriter of Eggs Over Easy happened to read the article and got in touch through the miracle of the internet. To cut a long story short, Martin Johnson took the opportunity to interview Jack O’Hara about his time in ‘70s London, the dynamics of Eggs Over Easy and the background on how he hooked up with fellow band members Austin De Lone and Brien Hopkins, and to confirm the facts behind some of the myths that have grown up around the band. It soon becomes very clear that Jack and his bandmates were just trying to make a living and be true to their own musical values, rather than to make any ground-breaking music that would subsequently change the course of ‘70s music. Jack also shared the fact that now he has largely retired from the music production work that has occupied him since Eggs Over Easy disbanded in 1981, he is looking to get some of his new songs out. Martin Johnson will be keeping in touch with Jack O’Hara and will keep Americana UK readers informed of any developments with his new music. In the meantime, if you want to get the actual lowdown on what happened all those years ago, read on.

Are you retired now?

Well, here’s the thing, I remain active creatively and for a living, over the last thirty years, I’ve been doing live sound in New York. I’ve been working with music in the studio, live and performing all this time. You could say I’m retired but I’m still pretty active [laughs].

Have you been engineering and recording?

Exactly, producing and writing. I’ve got over fifty songs I’ve worked up over the years.

Before we really get started, I’ve got one question I must ask you. When you first got to London and Eggs Over Easy were kicking your heels due to record company issues, did you tell the manager of the Tally-Ho you could play jazz? That has gone down in music folklore, but is it true?

That is not true [laughs], and I’m so glad you asked me that. What caused you to ask me that?

I’ve always wondered whether it was an urban myth or the truth.

It is complete bullshit. I don’t know who made it up, but I have always resented that, to tell you the truth. The real story is better for me. I will tell you exactly. I got cleaned up on a Monday night and walked up there, I might have told the band I was doing it, and I walked in, there may have been someone playing there or maybe not. There was just one bartender, who called the manager, and somebody had told them we were in town, and we were doing a few things like working on a record, but we just wanted a place to play in the neighbourhood and we would come and play for free. He said he would go talk to the governor upstairs who was the female owner and she obviously lived upstairs. He said, “If you can describe your music in one word, what would you say?” and I said “Fun.”. That is just what I said, fun, and he said OK and went upstairs and he came back down after ten minutes and said, “OK, why don’t you come around next weekend and do a show”.

We had a little PA that was on loan from the Robert Stigwood Organisation, it was just some PA that was laying around their offices. We had been doing a few shows that required us to bring something. There was a piano there, a baby grand because it was a jazz club, and we got a little brown Princeton guitar amp and a little, like a two-take cabinet with a Bassman head, and that is what we played with, right. We went there and played one night and there were around six people there, and we met this Canadian girl who was in the audience, and we just had a chat, and it was nice, and we played a couple of sets. The next time we came back there was like twice as many people, and the next time there were like four times as many people and it just exponentially, word of mouth, grew. I have to say, and I’m telling you more now than you asked for, and one thing I want to make sure is you can’t discount John Steel in the equation.

That raises the question of why you didn’t have a drummer in the first place and how did you get John Steel?

We were a trio of songwriters, and up to that point, it was about our material. I also wanted to just pick up a point in your earlier article where you said we were a seasoned bar band at that point, but we weren’t at all, we were basically three songwriters who were very compatible in style, and we had a good vocal sound. That was the attraction really, that is what we were. I personally had had experience of playing in pubs and stuff, but not so much the other members, Austin De Lone and Brien Hopkins. When we went there to work with Chas Chandler we did some stuff as a trio, and then he enlisted a local drummer, who was much younger than us, and he played a few sides with us and Chas is recording. Somehow, we really wanted Johnny to play with us, so he came in and did one cut on the unreleased stuff from 1971 (released on 2016’s ‘Good’N’Cheap: The Eggs Over Easy Story’) and Johnny was Chas’s assistant at that time, he was in his office and he was his number two guy.

He was helping us, getting us to gigs, renting us a truck and stuff, and he was more or less on the team. We cut a couple of more things in the studio with John after that, that didn’t see the light of day. For him it was just a good thing, a lark, let’s play some music, and I can’t tell you how exceptional as a musician he is. It wouldn’t have happened like that without John is all I can tell you. It was the perfect storm, the guy loved American music, obviously, look at the Animals, and they made brilliant records. Without those guys in the studio making those records, it was not like today where you get a few heavyweights in to help production, those were humble guys from the North who came down and created as a unit. That’s how we got involved with John, and he was at the first Tally-Ho gig and it soon turned into three and a half days per week, a very nice gig.

It was interesting when you were talking about your PA because Nick Lowe supposedly heard your low-fi quiet sound and thought, yes, this is the way to go. From what you said, you simply used what was available to you and there was no big thing about it.

No. I still have the guitar right here with me [laughs]. It is a Kay guitar, there are great pictures of Jimmy Reed on one of his album covers featuring this type of guitar, and Howlin’ Wolf and other people. The thing is, the model at that time was that glam was just starting to come on, and hard rock was already there with its bigness, and we were more like a James Taylor or a Van Morrison dynamic as far as being songwriters and pretty organic music. It was revolutionary that we were playing off-brand guitar through little amps and a real piano, and just rocking the shit out of the joint [laughs]. Because that is what it was, and it was joyful on our part and joyful for the audience, so collectively it was a very joyful experience.

There was nothing precious about it. I have to say I never really thought about it too much until recent years when we have been getting more attention than before. The thing about us that was punk was that we just didn’t give a fuck, you know, we just didn’t give a fuck [laughs], and we did whatever we wanted to do. We did ‘Brown Sugar’ when it came out right on the stage at Tally-Ho, we did Ray Charles songs, old rock’n’roll, Sam Cooke songs, and we did our material, whatever we wanted to do. There were no lines drawn, it was just a true, natural organic experience.

Again it may be another urban myth, but you supposedly had a repertory of over a hundred songs to choose from.

Yeah, we were prolific and there were three of us who were all genuine writers, in our own right. We had stuff we brought to the band from before we were the band.

How did the three of you get together in the first place?

I had been in LA making records as a bass player with a couple of people, one guy named David Blue who was kind of a Bob Dylan cohort and in his entourage in the mid-’60s, then I made a record with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot in ’67 in LA as a bass player, and I just wasn’t learning any music, you know, when I met some people who were friends of my girlfriend who came down from Berkley, California. I went to Berkley, and I was involved with some bands there, and through that process, Audie came to our band’s house. He was a songwriting partner with this person, Alan Chance, and they had written a few things, including a song Linda Ronstadt had recorded. It was a very communal situation, and Audie and I started writing a couple of songs and we really sparked, you know. We became a duo, and we were playing around little coffee houses in San Francisco, The Coffee Gallery on Grant Street was one, and I had history in New York and at one point Audie went east to visit his folks, who were in New York, and I came back to New York and my musical education was in The Village from 1965 onwards as far as this whole culture goes.

We just stayed in The Village and played around the coffee houses and stuff and Brien showed up one night to perform, he was singing ‘Henry Morgan’ and a few other songs. Audie and I just looked at each other and went wow [laughs], we could feel a kinship and so we got together one night and sang, and that was it. It was almost instantly enough, and it was really great, and he got the support of us as musicians, and likewise.

Your sound was familiar but different, it was like everything in a way.

This may sound funny, but when people ask me about my music, how do I describe it, I say, “Refreshingly normal.” [laughs]. We were never striving to be different, we just wanted to express ourselves basically.

You laid the foundations for pub rock in London, but you recorded your debut album ‘Good’N’Cheap’ back in America. Did you ever regret not staying in the UK?

We wished we could’ve, but our visas had run out, we were laying low, and we wanted to get a record deal and our management was in the US. Chas would have liked us to have stayed, we had that record in the can and it only turned out to be demos for eventually the record we made for A&M. It was just difficult to stay, and we were homesick. Basically “Pub Rock” didn’t happen for a good amount of time, a year or nearly two, after we left, even though the seeds were sown, I guess.

I went to London in the Autumn of ’73 as a student and it was just really starting then. You had left by then, but your name was legendary. A few people had heard of you but hardly anybody had actually heard you.

It is crazy man, just so crazy. It was just such a perfect storm, how that unfolded, who we were, it is almost like the opposite of bringing coals to Newcastle. We were exotic in London, our music was an exotic experience at a certain time and place, but it was perfectly normal to us. There was the time around ’75 when Dave Robinson (Brinsley Schwarz’s manager and founder of Stiff Records) said why don’t you come back, we have this thing going.

Quite a big thing as it turned out [laughs].

Yeah, a big thing but who knew, we didn’t know and he didn’t know [laughs]. We didn’t have the means and just to raise thousands of dollars for plane tickets and visas and all that stuff was beyond us so we missed that boat.

If the stories are right, you influenced Dave Robinson, did he have any influence on you?

He heard us at The Marquee and that is how we met, and I have no doubt that once we met, he was very enthusiastic about us and he brought the guys around, you know, The Brinsleys, and he promoted us as well. He had us on a gig, just outside of town in a concert hall with that Irish band he was promoting at the time, and we did a concert with them and the Brinsleys and it was nice. I now realise he was involved with the build-up at the Tally-Ho because he was just telling everybody all about us, all the guys were, the Brinsleys were. All the roadies from the big bands used to be there in the audience. The roadies were in high-heeled boots and rooster haircuts, they were more glammed-out than the stars they were working for [laughs]. They would be there, and they were cool, and Jimmy Dewar would come around, Frankie Miller came around, it was just so friendly and casual we didn’t think anything of it, honestly, other than this is great. We had no sense of any industry-type implications at all.

A golden period, and as it turns out, extremely influential.

I guess so, that is what they say. Everyone has been cool, and it has been really great to be acknowledged, you know. It is always great seeing Nick, and I love talking to Dave, but I haven’t seen him over here since the late ‘70s, but I reconnected with him around the time of ‘Good’N’Cheap: The Eggs Over Easy Story’.

Your debut album ‘Good’N’Cheap’ was produced by Link Wray. What was he like?

It was a lovefest, man. Link is like a five-year-old. There is a well-known venue called The Gaslight on MacDougal Street, right in The Village, and that is where Bob Dylan got his balls and Dave Van Ronk used to run the shows there, it is like deep bohemian Village songwriting history there, by the time we rolled around in the ‘70s it was a contemporary rock venue and Link had just made a record on a major label, Tommy Kaye produced it I think, like a real pop producer, and so we shared the bill with him. We were shopping for producers at the time, and our manager was taking us around different established producers in New York. We weren’t really clicking with anybody, and Link just loved us and offered to produce us and we took him up on it [laughs].

I have to say this, there are three vinyl records in our boxed set, and none of our producers messed with our sound. That is very unusual, I think, certainly these days. I can’t remember anybody suggesting we  change anything on the music we presented, they just wanted us to do what we do. Link was certainly like that. He was just having fun behind the mixing board, making references to ‘Star Trek’ as he talked back to us on talkback [laughs], then he would be telling us wild stories about growing up. There is this song called ‘Song is Born of Riff and Tongue’ and he played beautiful lap-steel with a kitchen knife. It is Brien’s song, and it has got a high-pitched voice melody, and that is Link back there playing with an electric guitar on his lap just playing slide, very nice. He was really pleasant, he was easy and it was like a couple of weeks in Tucson. I wrote that song ‘Night Flight’ on the plane on the way to Tucson, I was flying by myself because the guys were already there. We just went in and banged it out in the studio, learnt it real quick, worked in the house and tracked it. It was great working with Link.

change anything on the music we presented, they just wanted us to do what we do. Link was certainly like that. He was just having fun behind the mixing board, making references to ‘Star Trek’ as he talked back to us on talkback [laughs], then he would be telling us wild stories about growing up. There is this song called ‘Song is Born of Riff and Tongue’ and he played beautiful lap-steel with a kitchen knife. It is Brien’s song, and it has got a high-pitched voice melody, and that is Link back there playing with an electric guitar on his lap just playing slide, very nice. He was really pleasant, he was easy and it was like a couple of weeks in Tucson. I wrote that song ‘Night Flight’ on the plane on the way to Tucson, I was flying by myself because the guys were already there. We just went in and banged it out in the studio, learnt it real quick, worked in the house and tracked it. It was great working with Link.

Were you pleased with the record ‘Good’N’Cheap’?

Honestly, no because in those days you get the chance to do something only once, and that’s it. It is not like let’s develop, and it was like you said in your article, it fails in comparison to a good night at the Tally-Ho. I love the material, and we did our best, but we weren’t very experienced in the studio. It is frustrating to have it not feel as powerful as we had experienced it often. That is true of anybody, I’m sure The Beatles felt the same way [laughs].

There are very few studio albums that have the excitement of a live recording. I think they are two different animals.

There are great recordings we have always heard that rock, obviously. I think ‘Night Flight’ really rocks, it has got a good spirit, but the guitar tones, that guitar is making some incredible guitar tones [laughs] as far as standards of exciting lead guitar go. We were happy to be recording, I was frustrated by the fact we didn’t really capture the essence that you had referred to. That is just an honest answer, you know what I mean.

You may have been disappointed with it to an extent, but it has stood the test of time.

It seems to have if you take people’s word for it. Artists are never really happy with their work, they never think they have got there.

The album cover is just superb to my eyes.

It is iconic [laughs].

What happened in America? You had a good album under your belts, and you had started a major wave of music in London that would eventually influence the world so you had some momentum. Why did you simply disappear under the radar at that point?

The UK thing didn’t exist yet as far as momentum and opportunity for us went. The real problem is I feel that as people we weren’t a business organisation, that is the simple answer. We were not a business organisation, and we were not ready for primetime. Basically, we went down to LA to make our second record, and certain things transpired that weren’t business-like and they neglected to renew our contract. From that point on there weren’t any opportunities for us, and we were so good we could just make a living doing what we do but the climate just got more pop at that point. Where we were, we liked to live in Northern California which was a personal decision, and it was good for us and we were very creative in that period, there was a lot of stuff that got created. We were estranged from our management, and it just wasn’t going to happen. There were no real opportunities for us. It is funny, we were just in that crack, it was before indie radio, it was before college radio, there was basically nobody to fall in love with us at that point. A band like NRBQ, when did they happen?

They started in the late ‘60s, artistically peaked late ‘70s and started to happen in the ‘80s for real.

For them to be celebrated etc was like a ten-year gap. For those guys, there were avenues for them to be appreciated that weren’t just mainstream, power pop or however you want to look at it. Nick is brilliant, ‘Pure Pop For Now People’ is just brilliant and what he did and how he did it, you know, we never would have done that. That was him and Dave Edmunds, Elvis Costello and everybody else. I would like to think that if we went back there in ‘76 we might not have clicked with that situation, we certainly weren’t angry young men, which was Elvis’s image, even though he is a brilliant songwriter. I’m just talking about pure business, not the man [laughs], what he was promoted as and what he was selling, you know. It was new wave, which was the far side of punk, that anger was a very real thing in the UK, it was a very real social situation. We weren’t any of that, we were a good time band [laughs], and I don’t even know if we went back there and joined the party whether we would have had any impact in that world. What do you think?

We will never know [laughs].

That’s right [laughs].

It sounds like Eggs Over Easy just fizzled away. You had legal issues with your second album, ‘Fear Of Frying’, when the label went bust.

That was like ten years later. We didn’t really fizzle, we survived from ’69 to ’81 and we were a working functioning band. ‘Fear Of Frying’ was a small label that Lee Michaels started around ‘78/’79. He ended up buying a guitar store I worked at, it was like a main store. He built a little studio in the back, and he actually taught me how to engineer, how to board engineer. He was also shopping for bands around the country, two or three bands, to put on his label and he had never heard of us. We were just all business-like and we delivered the music to him, and he said I want you guys on the label. That was wonderful, and we made the record and he engineered it and produced it, and once again he didn’t mess with the music. I went to his place in LA, and at that point, the band was maybe apart again because at certain times we were not functioning for a six-month period or something. Like Audie went out and worked with The Moonlighters and got produced by Nick and all that stuff. Audie had a lot of opportunities, which is rightfully so because he is such an accomplished musician.

I went down at some point and mixed the record, and so we had around 1,000 copies, but that label and business never happened for Lee. It was just a creative experience that we had that he afforded us. I like a lot of those tunes but ‘Scene Of The Crime’ is just perfect for me, I am very proud of that as a band and as a writer and arranger. I am extremely grateful for that recording, and I always urge people to listen to it. As I said we didn’t fizzle but just survived for years and years, and there were very few opportunities. If we were of a different mind maybe, but for us, it was about the music. The music was genuine, it was about our lives as individual writers, we wrote from our perspective, and we were really not trying to fit in, there was no striving to be accepted [laughs], there was no moulding.

Some people would say you succeeded.

Yes, yes exactly. We did succeed, obviously. Those are my personal values, and I came up in an artistic type family and there is no way I could have done it differently given how I am as an artist. I have this song and the lyric is “It is a luxury to be poor most people can’t afford it and I’m working towards it and I’m really not far from my goal.”.

Audie seems to have stayed out in California and he seems to have worked steadily for the last forty years since you broke up. He also seems to have been working in broadly a similar area of music. He has worked with Dan Hicks as an example.

That is our tribe. Dan Hicks lived in Mill Valley, and we all did stuff with Dan. We backed him up and we were called The Opinions [laughs]. I also did a show with him in New York with Conan O’Brien, he asked me to play rhythm guitar with him. That was an exciting experience.

It was a great loss when he passed five years ago, wasn’t it?

Yeah, he was one of a kind, that’s for sure. Did you ever see him live?

No, I didn’t, just his recordings.

He was fun, just a lot of fun. He was just one of the most intelligent people, and he was fast company for me, I couldn’t keep up with him.

Coming back to yourself, why did you move more to the backroom with your engineering and what have you?

I got married, I came to New York, and we wanted to have a kid and I had to have an income. It was natural for me to do that, I knew enough about it and I wasn’t going to go and start programming computers. Basically, I just took the opportunity that was there, and it worked out for me in the long run. I’m appreciated and I’m able to bring my musical sensibility to situations, and I empathise with the artists, and I support them completely. I just want to help them accomplish what they are trying to accomplish. From my perspective, I feel that I am a novelist and I like writing and I’m writing all the time. I have some basic song demos, but I really stand on the writing.

Do you have any real plans to try and cut a record or something?

It is simply down to budget, period.

Have you thought of crowdfunding?

Here’s the thing, I started working less about three or four years ago because I had had a really great job at The Blue Note Jazz Club for 10 or 12 years, which was a really beautiful period with lots of great music and I learnt about a lot of stuff, and after that I was semi-employed. At that point, I started going out to these blues jams at night and I was mixing with the musical community. Most of that community hadn’t heard me play and didn’t know about me, and I managed to get good relationships with good musicians. That was a very nice development over the last five years.

I now play around with them, I play for them, they play for me. I had a good steady gig at Lucille’s, B. B. King’s blues club on 42nd Street, which is now defunct. So, I moved to the back just because I needed to earn a living, and also the music changed so much it was like Flock Of Seagulls and there was so much music I couldn’t relate to and it didn’t need me. I just had to wait until the noise died down, forty years of noise [laughs]. Last year I was just ready to start presenting myself and I figured the best way to present my songwriting was with my acoustic guitar, a good keyboard player and a percussionist. When I send you my stuff you will know why I thought that. I now had the resources, I had people who wanted to do it with me, I had places I could do it, and two things happened, first the pandemic hit which killed everything and I had to have minor surgery on one of my hands and that took four to six months to really heal. I’ve just had the same surgery on my other hand, and I have another few months to go with that. I did a gig the other day and it felt great, so I’m fine with it.

It is really hard for me to pull the whole thing together and present myself, get an image, go out and book gigs, go out and crowdfund for a record. I’ve invested in recording equipment, I basically didn’t want to go spend $500 to $1,000 in a studio and not get what I wanted, be it the musicians and it is more about the people, can they play what I need to be played. Now I am meeting people who can and willing to, so it is ahead of me as far as I am concerned. I would still like to make a really good presentation of what I do.

This could be your chance.

From now on.

Fifty year’s experience, a new set of songs and you know what you want to do.

It is what I do do. I only do what I do, and I get good appreciation in my world and I need someone to fall in love with me, basically, on a musical and business level. I need an advocate because I am ready to go. The only problem is there isn’t a music business, it is art, it is all art to me. I just feel more functional than ever.

It is probably easier now to get music out than it ever was, but because of that, it is harder to get your music really heard.

There is a crazy amount of records released every week in the world in the current circumstance where everybody is trying to get their product out. You know what is great, I sent this package to Dave Robinson, and he really enjoyed some things, and he sent it on to Paul Carrack and Paul was wow that’s not bad, which for him is high praise. It is very hard to get people to record your stuff when the only money is in publishing. It is a rare person who will go ahead and record somebody else’s song. A smart business manager would say this song is going to help sell the other nine songs on your album, and that is my perspective [laughs]. I am never going to stop doing what I do.

What people want from me are those songs I’ve demoed. I’m close to getting a site set up but my priorities change day to day with life maintenance, equipment maintenance, health maintenance.

I was going to ask what you have been doing for the last year or so.

Just taking care of things, health issues and just organising my life, it has actually been great all this free time, it has been a godsend.

At AUK, we like to share music with our readers, so can you share which 3 artists or tracks are currently top three on your personal playlist?

I never really listened to music, and I never owned a record player as a young person, I didn’t get one until I came here when I was about 35. I was always in music, and I came to The Village when I was 17 or 18 years old, and I started getting involved directly. I was hearing Muddy Waters, Joni Mitchell, Paul Butterfield’s Blues Band and I was also hearing Eric Anderson I was getting a straight shot right in the clubs that I had access to, even if I wasn’t playing in them. I’ve never studied records or anything like that. We had a few records in England, we had Stevie Wonder, Carol King, Van Morrison and The Band records of course.

I’ve been working as a soundman all these years as well, so I was inundated by music, and I wasn’t listening to music when I came home. I’m hearing all these sounds and my biggest source for music that is new to me is in films and some current cable television productions. If I hear something I like, I find out who it is and what they’re about. There are some brilliant music managers out there, and these things are not necessarily current or new, just new to me. [laughs]. I will listen to SiriusXM as and when I need to for a particular performer or singer-songwriter for a handle on a new artist or production values. I’ve got to think of something I heard recently that I loved, but I can’t think right now. My own songwriting comes from inside me, which has always been the case [laughs].

I do hope you manage to get something out.

I will. I’ve got to tell you this, there is a great DJ in Melbourne who plays the demos whenever she can. I’ve always wanted to get real versions, but in the end, the demos stand.

I’ve not sure how many UK fans you have left, we are all getting old, but do you have any message for them?

I was talking to Martin Belmont, we did a show 7 or 8 years ago up in Camden, and that was kind of fun and we played a bit, and he played one of my tunes on his radio show recently. His show is a good listen. I’d love to come to the UK and do a solo acoustic show, that should be pretty manageable.

Hello Mr. Johnson. Thanks for this interview. Just found it. I’m from the north east of England and I like blues music. I admit I’m no expert. I was in New York in, I think, 2005, and I was in Lucille’s Bar at BB King’s. Jack O’Hara was playing and I really enjoyed it. During the interval I approached him and we started talking. The first thing he said was “You’re a Geordie”. Stunned. But he explained that he knew Chas Chandler and could tell from my accent where I was from. I had never heard of him. I asked him about people he had worked with and or knew such as Mike Bloomfield and he was incredibly friendly and talkative. Then he had to go back to work.

It was only when I got back to the UK that I found out who he was and what he had done. The fact that I didn’t know him made my toes curl with shame and embarrassment. So I bought ‘Good ‘n’ Cheap’ which I still have. I tried a number of times to find an email address just so I could apologise for my ignorance but never succeeded. So, I really enjoyed this article (and my toes still curl).

Hi Austin, I’m always amazed at just how small our great big world can sometimes be. Jack O’Hara through his music and the influence his music had on other musicians has made a difference even if he is not a household name.