“Songwriting is a journey of discovery.”

Montreal singer/songwriter Rob Lutes is a jack of all songwriting trades and does his best to master them all, from solo and band recordings and performances of his own music to duo shows with Ontario guitarist extraordinaire Rob MacDonald to the supergroup Sussex with multi-instrumentalist Michael Emenau. And let’s not forget his side gig as a veritable fountain of knowledge on the long history of popular music in America and Canada. He offers sessions to all ages and cultures on the many different genres of music from the 1500s to present day.

Asked how he manages to keep all these facets of his career running smoothly, he has a story to tell, of course, about string theory (not the one concerned with theoretical physics). It’s something he picked up from reading Peter Eagle Sims’ book, “Little Bets.” The idea is to wrap a length of string around your thumb and fingers on one hand. Each digit represents a different slice of your career’s pie chart.

“It’s a simple concept,” Lutes said. “Writing, playing music, workshops, whatever it is I do, when one of them is pulling hard, work at it but don’t cut the other lines. In 2024, Sussex is one of those strings around a finger that he’s tugging at present. The band’s third album, “Shine,” was released in September, on the heels of its lead single, ‘ Shine Down Every Day.’ As he explained, “The song contains the spirit of the old tune ‘Shine On Harvest Moon’ by the vaudeville tandem of Nora Bayes and Jack Norworth. It serves as a hint of that glorious time in American music, the early 20th century, with some naivete and simple wisdom.”

Lutes and Emenau both grew up in Rothesay, New Brunswick and took divergent paths before winding up in Montreal. You can hear a wisp of the Jean-Philippe Bordier (guitar) and Pascal Bivalski (vibraphone) Quartet in the blend of Hot Club and Tin Pan Alley jazz that shows up in the new but old-sounding melodies of Sussex.

Lutes is an impulsive songwriter who picks up a pen and paper as soon as an idea or emotion burrows into his consciousness like planted seeds of memory that grow into vibrant songs. Some come from surprising sources like the old-time tunes that he delves into in his American Popular Music workshops, where the tradition of breaking rules and making beautiful music is paramount. As Lutes likes to say, “Melody was king back in the Tin Pan Alley era, and that is where I typically start.”

Like most anyone who lives and works in the province of Quebec, Lutes is bilingual though you could say speaking the language of music makes him trilingual. Fred Frith, expansive guitarist and founding member of the English avant-rock group Henry Cow once noted: “You don’t just shut out different languages; you use all the languages that you have when playing melodic music.” But you also have to tell a compelling story, and as you’ll read in this interview, Rob Lutes is quite remarkable at that as well.

You were born in Toronto (1968) but moved to New Brunswick at a very young age, the 6th of six children.

I left home at 16. My parents moved to Montreal on my last year of high school. I went to university in Ontario, Nova Scotia and PEI. Then, when I was 22 I met a girl in Montreal, who came to visit me in PEI, and we have a daughter born in 1992. We moved back to Montreal and have been there ever since.

French people make up 65 percent of the population in Greater Montreal whereas English are 14 percent and all others 21 percent. Even though 88 percent of the people are fluent in French, did you find it challenging to carve out a place for yourself in the city?

Montreal is the hub of music in eastern Canada. There are festivals. It’s a good music city, especially with francophone music. It has a massive music scene that hardly anyone outside of Quebec knows about. The provincial government is very supportive of the arts. They say the artists helped the French win the revolution, so royalty rates are highly respected, much better than in the UK. America or the rest of Canada. Quebec is more like France in that regard. Anglophones are in the minority here, and the francophones don’t like us very much. It’s kind of like the right and the left in the U.S. If you go anywhere in the States, everyone is super friendly, but talk politics and you might get in trouble. Language is the issue here. They want to preserve French and make sure things don’t change.

From living there for two to three years during the time (1976-1985) René Lévesque was premier of Canada, I was well aware of his role as founder and leader of the Parti Québécois and defender of Quebec sovereignty, often comparing it to the American Revolution. The PQ won 49 percent of the National Assembly in the 1981 elections, which made the referendum on secession from Canada such a time of division, not unlike what we see in American politics today.

They had another vote to separate in ’95, and it narrowly lost by less than a percentage point. A lot of English people left Quebec after that. When I travel outside Quebec to play shows, I never fail to meet someone who used to live here. Now, it’s getting even stupider.

Does Canada have its version of Nashville, a Music City?

Not really. Nothing like it. Toronto is really the hub. That’s where all the records get made.

Perhaps the most popular of the Americana band in Quebec has been les Cowboys Fringants. Their leader, Karl Tremblay, recently died of prostate cancer. The reason I mention this is that the renowned trumpeter Ivan Jolicoeur played with them and also sat in with Sussex.

Tremblay’s death was a big deal. People were crying in the streets. It was like W.C. Handy dying in 1958. Jolicoeur was with them for a while but was unceremoniously un-hired. He wasn’t part of their core. They went out on tour one time, and he never got the call. He aged out, I guess, in his sixties and has had some health issues. It was a huge pleasure having him on our record. But back to Sussex, it’s mostly me and Michael with a rotating lineup. In the first lineup, there was a guy named Benoit Charest, who did the music for a film called “Les Triplettes de Belleville.” He was nominated for an Oscar. That’s one reason why we called Sussex a supergroup. Joshua Zubot was part of Sussex, and he is one of the top violin players for sure, having been with Patrick Watson and The Barr Brothers. Sage Reynolds on bass has played with so many musicians and bands around here.

This is the third Sussex album and the group seems to have assumed equal importance to other aspects of your career. Do you enjoy having so many options? Or can it sometimes be like, if this is Tuesday it must be Rob & Rob?

One thing about doing the singer/songwriter thing is that it’s kind of a lonely world. So, sharing the load became an attractive thing. I love playing with Michael but the vibraphone is so different the way he had his set up. I told him it was loud, too much, so he removed all the resonators. It’s one of those instruments that is nice to hear, but after three or four songs, it’s enough. Those tubes are like amplifiers and he replaced them with a piezo pickup, like a guitar pickup on every key. He ran it through an aggregator so it all comes out as one signal. Now he runs it through a pedal board, so acoustically it’s a lot quieter, but those pedals can be used to make it sound like anything. He’s really adept at doing these textural soundscapes that I can play guitar over live. When he did that, it went into another realm. Sussex is entertaining to me. I’m not concerned how long it will go on, but right now it’s like I can pull out my box of chocolates and say, here Dean, take one. What’s your craziest idea for a record, and I get to do that with Sussex.

So, the new Sussex album came out in September, and it’s a bit of a departure from the others.

Yes, it’s very eclectic. It gave me the chance to explore sounds I’d always wanted to. This one is mostly my vision. Michael Emenau and I have known each other since high school. We played on the same hockey team at five years old and have been friends for years. We did some jamming, and I started listening to vibraphones in popular music. If you listen carefully, you can hear it in Bobby Hebb’s ‘Sunny.’ Even Motown and classic country, it’s not prominent but it’s there. Dwight Yoakam had it. So, I had this vision of using it because we tour with it. Vibraphone is kind of fun live; people are curious.

Most people would think of it as a jazz instrument – Gary Burton, Milt Jackson, Cal Tjader. Country music legend Charlie McCoy played harmonica mostly but also guitar and vibraphone. He’s the one playing vibes in the Elvis Presley movie, “Harum Scarum” back in the ’60s.

Exactly, and Michael can play all that. He’s a phenomenal jazz musician. I’m calling what Sussex does either country jazz or ragtime folk or Tin Pan Alley blues. Michael’s hero was Lionel Hampton, one of the big players in the ‘50s. Today, maybe 10% of the population might recognize his name.

‘Shine On Every Day’ was the first single from the Sussex album, kind of a blues/folk/Tin Pan Alley thing like you said. Then you actually do an old Tin Pan Alley tune, ‘I’ll See You in My Dreams’ by Gus Kahn.

To me, that was the best song of that era. Gus Kahn was such a great lyricist. Johnny Mercer called ‘It Had to Be You’ the greatest song of all time, and for him to say that means a lot. That song is very harmonically complex. Isham Jones, the band leader from Illinois, has a great version. I played it for my guys and they kinda knew it, but it’s very unusual.

Wouldn’t you say many of the songs from that era are very sophisticated musically?

Melody was king. This was an era of melody and lyric – what Sammy Cahn called song architecture – where a word lands on a note and it all makes sense. Dylan rambles through lyrics and the melody is in there but it moves around and is hard to follow. Kahn’s song is such a beautiful meditation on bittersweet love. It’s sophisticated but very simple, like Irving Berlin language.

The next single was ‘Warning Light’ then ‘Un Canadien Errant,’ a co-write with Josephine von Soukonnov (Kinzaza). What is Kinzaza?

That’s a woman I knew. Her partner is Russian, and they have this band that’s very proficient technically. I wanted to do that song for a film, and she’s francophone. Her partner orchestrated it. That’s actually an old Québecois folk song from 1842 written by Antoine Gérin-Lajoie after the Lower Canada Rebellion of 1838. What happened was that there was a rebellion in Quebec in the 1830’s, mostly francophones though some Americans came up to help fight against the English.

The French have been on a serious losing streak for centuries. Wasn’t that after the Plains of Abraham battle during the Seven Years War, when the British victory led to the conquest of Canada?

The English were in control. Wolfe had won the battle, so the people rebelled. The British didn’t execute these people; instead they exiled them. They sent all these Québecois people to the States where they still have some cultural influence. So, this was the composer singing to all the patriots who had left, that he’d never see again.

Robbie Robertson wrote a song about a similar exodus called ‘Acadian Driftwood.’ That’s one of The Band’s exceptional songs.

That was about yet another exile. Same idea different history. The troubles in Acadia caused the expulsion of the Acadians during the rivalry between the French and the British over what is now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and most of Maine.

Will you be doing much touring in support of the Sussex album?

We’ll do a few dates then a few more next spring, some festivals, but it is a side project and the guys are booked with their own things. I feel it will catch its audience somewhere.

Has the live music scene rebounded from COVID days in Quebec?

The cost of tickets has increased and that has an effect. But, yeah, it’s come back. For me, some years everyone wants me to play gigs; other years not so much. What I can say is with the Spotify era, people able to release a lot of DIY stuff. There’s so much out there, too much for the available venues.

You have a strong fingerpicking technique. Where did you pick that up?

I saw guys in high school learning to play lead guitar lines, trying to be like Jimmy Page, and that was okay. But I wanted to be different. I loved Bruce Cockburn, Stephen Stills. My big moment was going for lessons in Toronto with a guy named Mose Scarlett. He played all those vintage tunes like ‘Darktown Strutter’s Ball’ and ‘California Here I Come,’ all fingerstyle. I took two lessons with him. We’d go down in his basement and I’d just watch him. That was it. He played sort of Travis style but a bit more sophisticated. I was able to record a little of it on cassette. So, I went home and finally figured out what he was doing with his thumb on a basic level. I went back to him six months later, and he said I was the only one who had ever figured it out.

I guess that’s part of the blues tradition.

Exactly. But he was also a very kind guy, and anyone who played acoustic in Canada knew him – Bruce Cockburn, Colin Linden, they all liked him. Mose taught Leon Redbone how to play guitar. Redbone was born in Cyprus then moved to London when he was 13 or 14. In the ‘60s, he came to Toronto. Mose was bitter afterward because he felt that Leon had stolen his schtick, but Leon just got it going on another level. Mose was an interesting character. I don’t want to disparage the dead, but he talked too much, drank too much, and live he was spotty. He was an amazing player but when he was drinking, he could get a little windy on stage.

You have a beautiful guitar. Would you say something about it?

That’s my 1934 Gibson L-OO. I inherited it from my brother-in-law. His uncle, Don Walker, bought that guitar for $60. He enlisted and went to World War II in the D-Day invasion and was the first New Brunswicker to die. My brother-in-law is a lefty and rather than reroute the bridge, he passed it on to me as the custodian and someday I’ll pass it on. It’s an iconic blues guitar. All those old blues guys played one just like it.

It looks in excellent shape.

It is but it badly needs a reset and those take about six months. It is so loud and resonant for such a tiny guitar, just a little bit larger than a parkour guitar.

What are some of your favourite venues to play either solo or with your band?

I’ve toured in Europe eleven times. There’s a room in a town called Vestzaktheater Het Zwijnshoofd in Bergen op Zoom that’s booked by a judge, Jos van den Boom. The bar has been open since the 1700s. The town is like one of those independent states in the 1600s that banded together to form The Netherlands. Ria Denisson is the woman who runs it now, and she is the great-great-great, maybe 7x granddaughter of the original owner. It’s special. You go in and have dinner with the presenter. There are lots of characters around. It’s dark and dank and you can feel its age. This woman comes and serves you. It turns out the back room has about 100 people. The owner does a show there called “Crossroads Radio” with lots of Americana music. He records everyone who plays there and broadcasts for his show. So, you play the show and the Dutch are just crazy for Americana and blues. When you finish, she offers you some of the best beers in the world. She gave us this Westmalle Triple Trappist Ale in a tulip glass, chilled like it’s supposed to be served. You know, I never drink when I play but afterwards, I’ll have a beer. Those beers are like 90% alcohol, but they’re so fruity and tasty.

One of those sounds pretty good as this oppressive humidity on the Carolina shore wears you out. What venues are favourites in Québec?

There are some rooms here that are very exotic and interesting to play. One is called, and it’s impossible to pronounce, Le Vieux Troyil in the Magdalene Islands (Les Îles-de-la-Madeleine). These are a series of little islands way out in the Atlantic. I’ve played there three times.

I’ve visited there. It’s around 150 miles off the coast of mainland Québec, but it has a surprisingly mild climate. Something to do with the weird way the water masses circle the archipelago. It’s kind of like Key West in Florida. Even in the middle of the ocean, you can go from island to island by the tombolos (pillows in Italian), sandy sediment built up that ties the islands together. But enough about geography.

Beautiful room, stage, atmosphere, warm and friendly, maybe 200 people there. When you open the door to the green room, you are right on the beach with the ocean behind you. Then there’s Café l’Échoeurie in Natashquan, which is the home of Gilles Vigneault, the great Québecois poet and singer/songwriter. I don’t love driving to gigs there, but the enthusiasm is terrific and there’s something about playing music in these end of the world type locations that’s magical. I mean, to get to the Magdalenes either you pay $500 for a flight from Montreal or drive to PEI and take a 5-hour ferry.

There’s a photo of you playing live at the Café L’échouerie in Natashquan, that shows what you described.

Bruno Simard was there and took this amazing shot, showing just how close the venue is to the Atlantic Ocean. That place is 1500 kilometers from Montreal. The highway ends not long after that and you end up in Goose Bay, Labrador, a big mining town. This guy took the shot of me on stage and sent it to me. Turns out he was a professional photographer on vacation.

Let’s jump around to some of your albums, like “Come Around.” The video of you working at this old typewriter on the song ‘Work of Art’ was confusing. Did that have anything to do with the song?

A friend of mine came to me with the concept. It’s kind of like the artist versus the songwriter. The artist is wanting to get to a certain level, while the person writing the songs is plugging it out in the trenches. The song is about a relationship, someone you cared about as a friend and imagined it would be an amazing experience to be with, but you never tried. It kind of remains in this place of potential where it could have been great, but somethings aren’t supposed to happen that way. The artist part of me is trying to get the other me to write something for this person to convince her it will work out.

Finding the wonder in your face is like sunlight dancing on the sea. So, he’s trying to create a reality by painting it.

It’s kind of like if the two of them got together it might not be great, but if you leave it as just potentiality it becomes a work of art.

‘That Bird Has My Wings’ has an updraft of spirituality. I can’t pretend to have a clue about the end But I choose to trust and try everyday It′s a matter of time until love will light my way.

It’s based on a guy named Jarvis J. Masters, who is on death row in San Quentin. He was sentenced for armed robbery, then got railroaded. something like what happened to Hurricane Carter. A guard was murdered and Masters was convicted of making the shiv used to kill him. It was later revealed inmates testified against him to get better deals for themselves. There’s a movement if you go to his website, freejarvis.org. The largest law firm in the US with billings of $5 billion is representing him as their one pro bono case of the year. He needs the governor to free him as an act of clemency, but freeing murderers is not a popular thing politically. He’s been in this 9 x 5 cell on death row since 1991. He’s turned into a Buddhist and his one way of conjuring freedom was to look out his window and see birds flying. The other prisoners out in the yard would throw rocks at birds for sport. Masters would yell at them from his window, saying don’t hurt that bird. He has written two books, one being “That Bird Has My Wings.” This is the coolest thing. I wrote to him and sent the song as I wasn’t going to release it without his blessing. I got an email back from him saying, “I love the song, Rob. Go ahead and release it.”

What songs from your other albums do you still play at shows, either solo or with the band?

You know, I worked on my songs really hard, especially the older records, making sure every word was right. So, I play a lot of them, but two I really like are, ‘I Know a Girl’ and ‘Constancy’ from “Truth and Fiction.” That album was produced by Dave Goodrich, who’s produced Chris Smither’s albums for twenty years.

The chorus for ‘Constancy’ is very evocative. Oh, come on now, we hide so well, Between the way it is and the stories that we tell, I’ll take your truth over any fiction, It’ll be a little like acquittal or salvation.

This was around the time I had met the girl who became my wife and was very much in love. But at some point, you find yourself struggling to say what you want and sometimes don’t even know what that is. We were briefly in one of those periods. There’s something about steadfast that can pull you though those times. She actually helped me write the song. But the other thing that’s great is people will come up to me and say what it meant to them. One woman, Tina from Trois-Rivières, told me it saved her marriage. At the time I wrote the song, I was listening to a lot of Smither’s music. He went to places that are uncommon, sometimes dark, but he always balanced it with wisdom. He has been very influential for me.

Do you know Chris Smither personally?

I saw him play when he came to the acoustic stage at the Montreal Jazz Festival. He had just put out the album, “Small Revelations.” It has such a different level of poetry. Like most people, I struggle with darkness at times.

As Leonard Cohen sings, I want it darker.

Cohen is a legend around here, and I love his writing. Big influence for sure. It’s like I love listening to him but at some point, you know, it’s enough.

‘Things We Didn’t Choose’ from “The Bravest Birds” album is one of your best songs. This love is happening again, Where it leads, we cannot know, We just follow all of the clues. Rick Haworth, the legendary Québec guitarist and producer (Daniel Bélanger, Michel Rivard, Richard Séguin) had high praise for the album. “Great songs, fantastic vocals, super playing and excellent production. What the hell else do you want from a record?!”

I’d been asked to go to this festival in Sackville, a little town in New Brunswick. I was doing this songwriting workshop, and when I do those, I write these little prompts. It was my son’s birthday, and I really didn’t want to be away from home. All my prompts had to do with birthdays – candles, birthday hat. When writing a song, I always tell people go with the subconscious, the first idea, don’t try to edit. It’s a journey of discovery. So, I wrote Light it up and let it burn, Put on your party hat. It’s the Paul Simon method of songwriting; you write a line and see where it leads you. My favorite saying is by this Buddhist monk, Ajahn Brahm, based in Australia. “Is it possible that every bad thing is really good if you just wait long enough? Who knows?” So, the song is about sometimes you can gain from negative experiences. The song had a central concept, and those are the easy ones to write. The hard ones are where you don’t know what the concept is, so you have to whittle it down to find out what you’re talking about.

You must have been in the flow when you wrote ‘Still Dark.’ Now I’m living on fumes that I brought from the past, The future’s a shadow I mix in a glass, With a furious mind that writes down these refrains, It’s still dark, it’s still night, I’ll go to bed again.

I worked hard on that song. It’s about a lost relationship. I played it once and someone asked if I wrote those lines, and it sort of pissed me off. Yeah, I did. But I believe everyone is capable of writing something meaningful. It’s a matter of allowing it to be rather than forcing it. Like yesterday, I did a workshop on spiritual songs. It’s for a Jewish group in New York. Some of the all-time great tunes have come from Jewish writers. We worked on ‘Bridge Over Troubled Waters’ and ‘Hallelujah’ by Leonard Cohen and Laura Nyro’s great ‘And When I Die,’ which she wrote when she was seventeen. Cohen’s song is so great. Some say he wrote 50 to 100 verses. But it’s overplayed.

When Jeff Buckley recorded it, the song got a ton of airplay on FM radio.

That’s the version I prefer. Just the vocal delivery is perfect. What I like to tell people is you can’t improvise poetry. You’ve got to work at it, right? People just want to write it down but it doesn’t work that way.

Let’s talk about the storytelling part of what you do. You must have an encyclopedic knowledge of music history. Richard Thompson has this album “One Hundred Years of Popular Music.” He’s a music historian as you are. And you have these amazing testimonials from people of all ages. “We didn’t quite know what to expect from a workshop that combines a performance, storytelling, history lessons and a chance to participate,” said Sylvie Bouchard, Chair of the Arbor Gallery. “We had fun and learned a lot about the early days of music in America.”

Over the years at different festivals, people have asked me to do workshops on the history of the blues. When covid hit, a guy who runs an organization called Réseau, networking for seniors, asked if I could do something for people who can no longer go out. I thought about it for a while. What if I took what I know and blew it up a bit and turned it into the history of popular music – American and in brackets Canadian? Doing research consumed me. I was a nerd for it, like giving someone what they love most. I started with the first hit song in America, ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy.’ It’s not a joke; it’s true. That song was massively important. So, I start there and build this timeline about what people were listening to. It’s fascinating. You get into these patriotic songs like ‘The Star-Spangled Banner,’ religious songs like ‘Amazing Grace,’ and kid’s songs like ‘Skip To My Lou.’ Then I get into classical, which was the popular music of the 1800’s. How did people hear of Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata” since there were no orchestras in America at the time? There were simple transcriptions for piano and flute. Then comes the minstrel music, which is tricky, revealing the dark history of songs like ‘Polly Wolly Doodle’ and ‘Oh Susanna,’ ‘Dixie’ and ‘Old Folks at Home.’ Another huge era was parlour music, Civil War music. The big story is what happened in America, Cuba, Jamaica, Brazil, where you had white music from Europe. The indigenous music was there but it wasn’t as accepted as an influence. Then came African music. The word for it is syncretism, when two cultures blend to create something new. So, when you get to blues, ragtime, jazz, r&b, rock ‘n roll and country, it’s all a blend of African and European styles. In Brazil and Jamaica, it didn’t develop that way. It became reggae, samba, Bossanova. This is the story I like to tell. Then you get into the writers and the songs, all their personal histories.

All that sounds like a massive amount of research and memory.

At one of the seniors’ workshops, a woman came with a book she said was being thrown out at the library, “A History of American Popular Music” by Phillip Simon, the preeminent musicologist in American history. It’s over 500 pages. There’s a 50-page chapter called ‘The Crazy 60s,’ but it’s the 1860s. There is so much detail. You and I might recognize 10 percent of the songs in there. It’s so much fun.

Will you write a book one day about the history of music in North America?

I don’t know. I am a writer and I worked in publishing for ten years. I don’t have time right now because I want to play the music.

What about an audio history?

We’ll see. It’s dangerous to do these things because I’ll say something then down the road I’ll find something that maybe doesn’t contradict it but adds nuance.

I looked around your site, and it appears the six-week course is very popular.

I can do a single course or six-week, but I also have ongoing groups. The group in New York I mentioned called Virtual Seniors has been going weekly or bi-weekly since the fall of 2020. With them, I did the whole history of Broadway in thirty tunes. When did Broadway start? Who were the big names? What I try to get at is the art, like how did this all happen? Then there’s New Orleans music, ‘Old Salty Dog’ by cornetist Freddy Keppard, then go from Buddy Bolden to King Oliver. They wanted to record Keppard and he said no because he was afraid they would steal his music. Instead, they recorded the Original Dixieland Jazz Band with Nick La Rocca. He was an Italian who said black people couldn’t play jazz. These little details are important.

I can remember there was a good song, ‘I Thought I heard Buddy Bolden’ by Jelly Roll Morton.

Louie Armstrong professed to have heard Buddy Bolden. He was born in 1901. Buddy Bolden went insane, so it’s very unlikely Louie Armstrong heard him. It’s one of those stories that get told, but Armstrong would have been five or six years old when Bolden was committed to a mental hospital. Jelly Roll Morton claimed to have invented jazz. I mean, no one did. The way I look at it, ragtime from the 1880s has got elements of jazz in it. It’s a little too structured, not relaxed enough to be called jazz. I talk about Scott Joplin, an amazing aspirational figure who had been forgotten until George Roy Hill used his music in the movie “The Sting.” That movie was set in the 1920s and ragtime was over a decade earlier, but it doesn’t matter. Joplin was buried in an unmarked grave. He had syphilis that went to his brain and caused him to go insane. He died penniless in an asylum. Imagine that! It was only after that movie that they put a headstone on his grave to honour his contribution. It’s all an ongoing tale that makes me curious what will happen to music in one hundred years.

Let’s change the subject to Rob & Rob. You two made a live album in 2011.

Rob MacDonald and I have been playing together since 1997. I was on a compilation album that he heard. He’s one of these musical savants, a phenomenal player, great ear, ability to do anything at a high level, pushing himself constantly but knows how to fit in. We’ve been playing together so long, we know how to leave space for one another, but it’s so rhythmically seamless. When we started, he was more of an electric guy, blues and rock, but he wanted to play acoustic. He has a resophonic guitar. I play acoustic and that guitar is just different enough to make a nice blend. We have a complicité, a great French word not used so much in English. It’s when they talk about artists on stage that have an understanding an interweaving of their sounds. We’ve gone past the point of ego getting in the way. When you’re young you want to be the guy that shines. I’m not in that place anymore and neither is he. It’s just really fun playing with the guy.

Where does the music come from for Rob & Rob?

Mostly from my own songs. It’s a joke between us that I always play something he’s never heard before. I’ll play ‘Down By The Old Mill Stream,’ ‘T for Texas’ or ‘Shine On Harvest Moon,’ but he understands song structure and can play them. It’s the Tin Pan Alley tunes where I can trip him up a bit. Like ‘Down By The Old Mill Stream’ is harmonically very bizarre, but it works perfectly. These tunes weren’t chord-driven; they were melody-driven. The chords follow the melody though sometimes it’s not the chord you’re expecting. For example, ‘Shine On Harvest Moon’ is in A minor but the chorus is in A major, just a weird change, but he still manages to follow.

I’ve been perusing your website’s photo gallery. Can I ask about some of the pictures there? On one picture it says Aunt Caroline and a banjo.

The reason that’s there is the banjo is a S.S. Stewart Thoroughbred, which was the first production line banjo in the US out of Philadelphia. The father started the company in 1890 and the son took over in 1902 until they went out of business in 1910. That was a banjo that my grandmother, who I never met because she died in 1967, bought at an auction in the 1940s. She bought it for my uncle, who never played it and put it in storage. Eventually, it came to me. I play the banjo sometimes and my aunt will come to the shows. She’s 88 years old now.

I’m looking at a much younger you in the Coffeehouse at Acadia University.

I’m on stage with my housemate, the singer/songwriter Dave Carmichael. This coffeehouse was where we cut our teeth as performers. It’s in Wolfville, Nova Scotia where I went for my undergrad degree. We used to play ‘Colours’ by Donovan and some John Prine, our influences at the time.

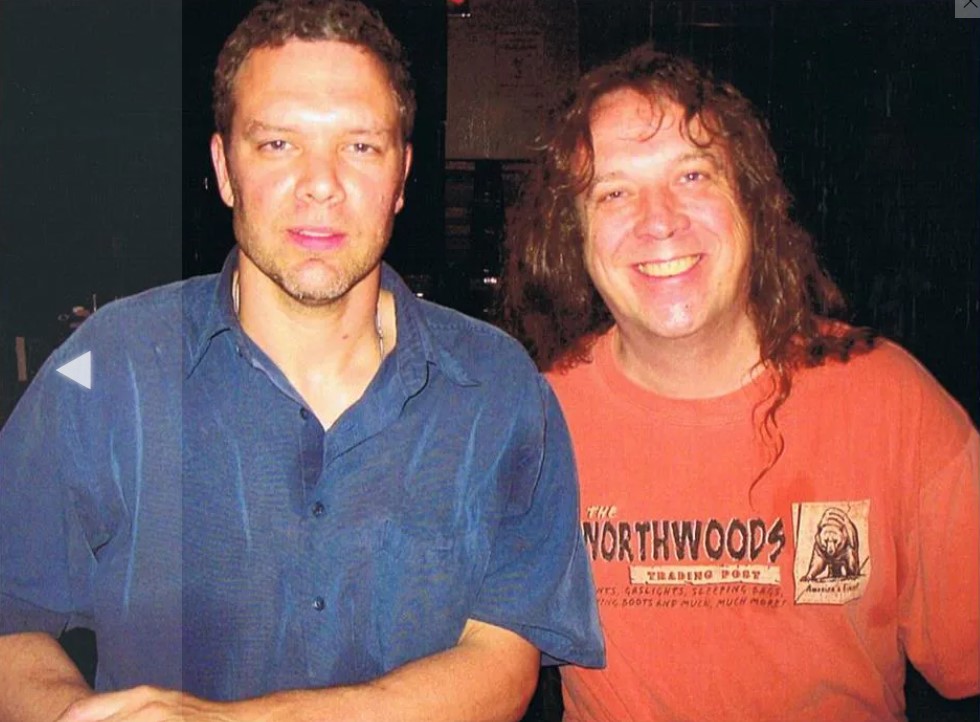

Here you are with John McGale, the guitarist with Offenbach. I still have their vinyl albums from the 1980s.

John died recently in a car crash coming home from a gig. There’s some debate about whether he fell asleep at the wheel. John not only played in Offenbach, but also solo and duo. He was from North Bay, Ontario and came to Québec where he learned to speak French like an English guy, fine but with an accent. He was adopted by the francophone community. He used to run a series at a little bar on the South shore of Montreal in St. Lambert. I had an invite to go every week and sit in with him. We’d play each other’s songs. He was a truly great guitarist and Offenbach, of course, was the big band in Québec for a long time.

This next picture is from a workshop in May 2015 about how to make a living in music.

I was invited to do this in Huntingdon, a little town just five minutes from the New York state border. I had to put all I’d been doing over the years into words. We had a good time. My main guy for how to make a living is this American entrepreneur and investor name of Peter Eagle Sims. His book is “Little Bets.” He said to not put all your eggs in one basket, but do many things. The way it’s described to me is your hand is your career, and you have a piece of string around every finger and thumb. So, writing, playing music, workshops, whatever it is I do, when one of them is pulling hard, work at it but don’t cut the other lines. It’s a simple concept and maybe not the central one from his book, but that’s what I took away. When one thing isn’t working, I’ve got something else and presently Sussex is one of those strings around a finger I’m tugging.

Here you are sitting on a stool at a workshop, Tremblant Blues, holding your young son. How many children do you have?

I have a daughter, 31, who’s pregnant, so I’m about to be a grandfather. Cormac from the picture is now 15 and is six foot four inches, and my other daughter is 11. One time Cormac was at a friend’s house whose father is a music teacher. He was told he had perfect pitch. He plays piano really well, but he gave it up when high school started.

You and Rob MacDonald played at the first Montreal Folk Fest on the canal in 2008. Was that held at Canal de Lachine?

That’s now defunct. Maybe 150 to 200 people were there, but it’s grown into something much larger as the Montreal Music Fest. At the time, it was a big thing for the folk community. It’s in a part of the city that was an industrial wasteland when you lived here. You take Atwater straight South and you turn right just before you hit the canal.

You definitely would want to take that last right. How about this picture of you with John Sebastian of the Lovin’ Spoonful? A lot older but still looks like the guy I saw play a show in the early 60s. when I was in high school. It was at Mountain Park in Holyoke, Massachusetts.

They would bring someone in of note as sort of a legacy gig. He’d lost his voice and can’t sing anymore. But he used to be wonderful in concert, told such great stories. His father was a classical harmonicist, so he knew all those people, everyone from the Greenwich Village scene. I loved hearing the Lovin’ Spoonful, and of course they had a Canadian connection with Zal Yanovsky, who was their guitar player from Kingston, Ontario. John called him Zally.

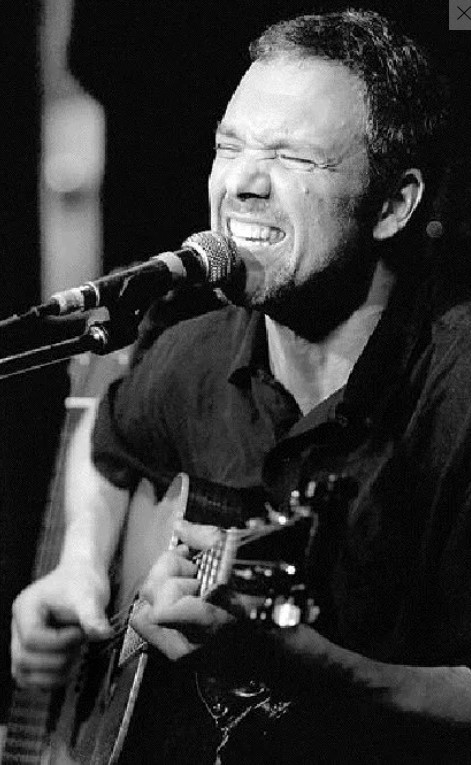

That guy was flamboyant. Well before KISS, I can see him in my mind’s eye sticking his tongue out and crossing his eyes. What a character! You say your favourite live shot is this one from the “Montreal Gazette.”

It’s one of my favorite live shots for sure. This one ran in the Gazette with the release of “Ride the Shadows.” Taken by the great John Kenney of the Gazette. That was in 2006 in this little club called The Green Room. I just loved the intensity in that photo.

********************************************************************************************************

Intense is a great word to describe the way Rob Lutes goes about his musical career, but it’s more of a relaxed intensity, which is of course an oxymoron but he exudes that as well as a humble confidence, not to mention being awfully good at his craft. Coming soon Rob & Rob (MacDonald) will be playing an exclusive AUK mini-gig, of which the video is almost totally recorded. You should expect the unexpected from this duo.