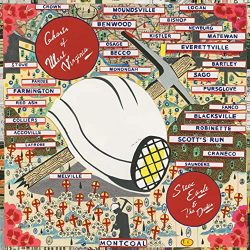

There’s nothing like a cause to get Steve Earle all fired up so when he was approached to write a set of songs for a theatre production about 29 miners killed in a coal dust explosion in Raleigh County, West Virginia in 2010, it must have seemed like grist to the mill. The play, ‘Coal Country’, written by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, featured Earle on stage throughout with his songs delivered solo in a “Greek chorus” format. There were seven songs in all and Earle has reworked them with The Dukes for ‘Ghosts Of West Virginia’, adding three related songs to flesh out the running time.

There’s nothing like a cause to get Steve Earle all fired up so when he was approached to write a set of songs for a theatre production about 29 miners killed in a coal dust explosion in Raleigh County, West Virginia in 2010, it must have seemed like grist to the mill. The play, ‘Coal Country’, written by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, featured Earle on stage throughout with his songs delivered solo in a “Greek chorus” format. There were seven songs in all and Earle has reworked them with The Dukes for ‘Ghosts Of West Virginia’, adding three related songs to flesh out the running time.

Not content to merely write a powerful set of songs commemorating the disaster, Earle has a contemporary take on it. He reaches into the mindset of the miners, acknowledging their dependence on big coal despite the numerous safety violations that led to their deaths and recognises that they are still exploited, most recently by the glib promises of Donald Trump. As an environmental campaigner who wants to end our dependence on fossil fuels, Earle notes, “That doesn’t mean a thing in West Virginia. You can’t begin communicating with people unless you understand the texture of their lives, the realities that provide significance to their days. That is the entire point of Ghosts of West Virginia. I thought that, given the way things are now, it was maybe my responsibility to make a record that spoke to and for people who didn’t vote the way that I did. One of the dangers that we’re in is if people like me keep thinking that everyone who voted for Trump is a racist or an asshole, then we’re fucked, because it’s simply not true. I wanted to speak to people that didn’t necessarily vote the way that I did, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have anything in common. We need to learn how to communicate with each other. And the way to do that — and to do it impeccably —is simply to honor those guys who died at Upper Big Branch.”

The current Dukes can probably be best described as a hard rocking bluegrass outfit and Earle takes full advantage of that here. The album opens with an acapella spiritual, ‘Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere’ which neatly allows one to equate the plight of the miners with that of exploited blacks. ‘Union, God And Country’ is a swirling and upbeat Appalachian bluegrass number with Earle celebrating the trinity of beliefs clung to by the mining community in an attempt to give their lives some purpose but the mood darkens on the ominous ‘Devil Put The Coal In The Ground’. With its fiddle drone, ferocious guitar and incessant beat conjuring a sense of claustrophobia, Earle growls magnificently on this fatalistic song which somehow gives one a sense of the toil and sweat and, ultimately, the danger, endured in the mines.

The upbeat tempo of ‘John Henry Was A Steel Driving Man’ disguises the grimness of Earle’s update on this hardy perennial as he sings about the heavy machinery brought in to carve out more coal in an hour than a team of Henry’s could have in a week. This march of progress is reflected on in the lovely and plaintive ‘Time Is Never On Our Side’, another fatalistic song but Earle then turns up the heat for the powerfully emotive diatribe of ‘It’s About Blood’. Here the pent up emotions are released as Earle voices the bereaved, damning the push for profit over flesh and blood, the band sounding feral and fierce with Earle concluding the song reciting the names of all lost in the disaster. It’s a mighty powerful song but the following, ‘If I Could See Your Face Again’, sung by Eleanor Whitmore, is perhaps more affecting as she reflects on a grieving widow’s loss on a beautifully winsome country number.

Of the remaining three songs, two continue the mining theme with ‘Black Lung’ a typical Earle country rock stomp in ‘Copperhead Row’ fashion – quite magnificent. Earle sings lustily here and his deep breath at the very end is a perfect touch. ‘The Mine’, which closes the album, must surely be ranked high in Earle’s canon as he relates the tale of a down at heel dreamer who is waiting for the call from his brother to work in the mines, a golden ticket he thinks as he ponders on the cars he’ll buy for him and his sweetheart, whose ring he has pawned. Nestled in between is ‘Fastest Man Alive’, a bit of an oddity here as it’s about Chuck Yeager, the first man to break the speed of sound (and the subject of Tom Wolfe’s ‘The Right Stuff’). He came from West Virginia and his pilot’s prowess allowed him to avoid the mines so, at a stretch it’s allowed here, and it has to be said that Earle and The Dukes attack the song with a fine sense of swing, firing on all barrels.

Whether Earle can manage to get his message across to blue collar folk duped by the current regime remains to be seen, but there’s no doubt that on ‘Ghosts Of West Virginia’ he has delivered a powerful and hugely enjoyable album. It’s dedicated to all who lost their lives in that tragic mine explosion and also to the late Dukes’ bass player, Kelley Looney.