A powerful tale of working life in the 1920’s Virginia coal mines.

Americana goes to the movies, as Gordon Sharpe takes another of his occasional looks at films making good use of an Americana-based soundtrack…

Film and music are, and always have been, interlinked, much to the advantage of each. following on from a recent article about Peter Bogdanovich this piece celebrates the work of two great independent artists of music and cinema. The film, ‘Matewan’, involves two individuals whose talents range across a variety of media. John Sayles is a film director, author, actor, editor and screenwriter. Will Oldham (Bonnie Prince Billy as he is now generally known) is a singing, song-writing actor who has collaborated with a significant variety of like-minded musicians. Oldham also starred as a very fresh-faced young actor in, ‘Matewan’, and I’d argue it’s his most significant cinematic achievement in a film that is an independent gem.

The Amazon website describes the 1987 production in the following accurate terms –

‘Written and directed by John Sayles, this wrenching historical drama recounts the true story of a West Virginia coal town where the local miners’ struggle to form a union rose to the pitch of all-out war in 1920. When Matewan’s miners go on strike, organizer Joe Kenehan (Chris Cooper, in his film début) arrives to help them, uniting workers white and black, Appalachia-born and immigrant, while urging patience in the face of the coal company’s violent provocations. With a crackerjack ensemble cast—including James Earl Jones, David Strathairn, Mary McDonnell, and Will Oldham—and Oscar-nominated cinematography by Haskell Wexler, Matewan taps into a rich vein of Americana with painstaking attention to local texture, issuing an impassioned cry for justice that still resounds today’.

Oldham plays Danny Radnor in the film and is something of an observer, part of as well as commentating on the unfolding events. He is the 15-year-old son of Elma who offers lodgings to the Cooper character, Joe Kenehan. Danny is also a coal miner and an aspiring Baptist preacher. The events depicted are part of a much wider conflict – the Great Coal Field Wars – and follow a familiar pattern. The owners use their wealth to subdue and subjugate the workforce – the forces of law and order generally protect the status quo and if they don’t then hired muscle in the form of private detective agencies is always available. One group of working men are often set against another as scabs – be they black or various immigrants. The use of ‘scrip’ at the company store gives the owner another hold over the workers meaning that only company ‘money’ can buy company goods – usually at inflated prices. Sometimes it beggars belief that so many vested interests did so much to turn the workforce to such potentially socially just models as the dreaded socialism. Many owners, by their practices, virtually guaranteed a left-leaning workforce.

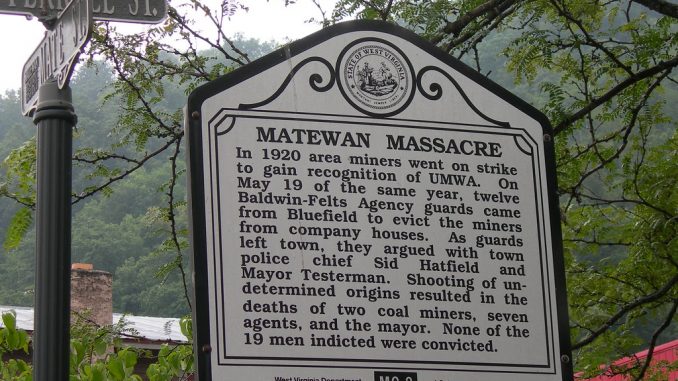

It must be noted though that in this story the police chief Sid Hatfield is sympathetic to the miners and is eventually assassinated by one C E Lively who has been a traitor to the cause of the miners throughout.

The film score features appropriate Appalachian-style music composed and played by Mason Daring who provided similar duties on many a Sayle film so could not be seen as a specialist. However, West Virginia bluegrass singer, Hazel Dickens, is and sings the title track, ‘Fire in the hole’, and she is an artist well worth investigating

Dickens is to be much admired for her pro-union feminist stand in life. She appears in the film as a congregation member and also sings over the grave of a fallen colleague before finally performing, ‘Hills of Galilee,’ over the closing credits. Also involved were the well-respected John Hammond Jr., Phil Wiggins (harmonica); Gerry Milnes, Stuart Schulman (fiddle), Jim Costa (mandolin); John Curtis (guitar), Mason Daring (guitar, dobro). The soundtrack was released on LP in 1987 and on CD in 1994.

From 1985 to the present Oldham has appeared in 10 other films and along with, ‘Matewan’. perhaps the two other most noteworthy are, ‘June Bug’, and, ‘Old Joy’. He has also appeared in 6 television productions. All of this whilst making virtually an album a year since 1993 – 25 in 29 to be precise and including what I consider to be a genre touchstone in, ‘I See a Darkness’.

The film itself owes much to the traditional western form with good – the miners – and bad – The Baldwin-Felts Stone Mountain Mining Company – protagonists. There are shootouts and assorted confrontations to match. Joe Kenehan, a fictional character played by Chris Cooper, is a pacifist union organiser who as he comes to town witnesses a fight between the locals and black ‘strikebreakers’ as they get off the train. He attempts to unite the locals as well as the black and Italian ‘strikebreakers’ as one union – which he does to a degree. Various ethnic groups are portrayed in simplistic terms – particularly the Italians – and the most cloying scene of all is when black, Italian and local musicians spontaneously play together. It’s nicely symbolic but feels a bit heavy-handed and obvious. The experiences they describe though are rather more pertinent. The Italians ponder whether it’s better to starve in Matewan or in Milan. Leader of the black contingent, ‘Few clothes’ questions his friend as to whether he would rather be back in Alabama. An Italian male suggests that if they strike break, the locals will shoot them and if they don’t work the company goons will do the same. A situation accurately described in terms of rocks and hard places.

The role of the church is important and Danny makes a good preacher and in one scene uses the parable of Potiphar to let the congregation know that Kenehan has been incorrectly identified as a traitor. Hickey and Griggs, two pivotal company thugs, find this all very amusing but fortunately, the townsfolk know their bible and Kenehan is saved in the nick of time. Sayles himself pops up as a preacher keen to impress that socialism and unionism are in fact only the devil in disguise. A further telling scene is when Kenehan tells Danny the story of the Mennonites, conscientious objectors he saw in Leavenworth, who were tortured because they stuck to their principles rather than obey prison rules. By way of peaceful self-sacrifice, they got their way and this is clearly illustrative of Kenehan’s belief as to how the union should conduct its business.

Whilst the Matewan massacre is a true event it is certainly the case that the plot has many fictional moments and chief management goons Hickey and Griggs are played with such malevolent gusto as to be hard to believe – they deliberately court trouble for no real purpose. If they each had a Victorian moustache they would certainly have twirled them endlessly. Both are vile beyond credibility although their disdain for the poor rural locals is probably not that far from the truth. It can’t be said that there is not some satisfaction to be had as Elma Radnor shoots Hickey or Hillard Elkins’ mother fires repeatedly into the already prone corpse of Griggs whose murder of her son is portrayed as the most gratuitous sadism – and totally stupid as C E Lively points out. His criminality is far more subtle and duplicitous as evidenced by the way he tries to manipulate local widow Bridey Mae Tolliver into betraying Kenehan.

Sayles does avoid the more obvious entanglements and declines to promote the attraction that grows between Kenehan and Elma Radnor. In that sense, the feeling remains one of drama rather than melodrama although her feelings are made clear as she breaks down by the side of his corpse as the shootout concludes.

It’s a polemic for sure, but American history and historians do not always play fair by the poor and their attempts to better their lives – and you might argue that it still doesn’t. Check out Howard Zinn’s, ‘A peoples history of the United States’ for an alternative view.

Many of the characters are stereotypes, whichever side they are on. Whilst James Earl Jones is compelling as ‘Few Clothes’ Johnson you might feel you have seen that smiling quietly spoken physically powerful morally upright character before. So it is with Mary McDonnell as the upright ‘widder woman’ and Josh Mostel as the slightly buffoonish but ultimately brave town mayor. Perhaps Sid Hatfield bucks that trend as he stands up for the locals and their just rights – believing that observance of the law is important whilst seeming to know that ‘they’ aim to kill him. As Kenehan points out, he’s never seen a lawman do that before. Hatfield is played with quiet conviction by Sayles regular David Strathairn. His later reward is to be gunned down on the steps of the McDowell County Courthouse with no one ever brought to justice even though C E Lively was long identified as one of the assassins.

A scene that sticks long in my mind is that wherein the newly arrived black miners are given their ‘induction’ wherein they are told that virtually everything that they will use is theirs to buy or rent, picks, shovels, helmets – you get the impression that the only reason they aren’t charged for breathing company air in the mine is that no one thought of it. The rules around ‘scrip’ are just jaw-droppingly preposterous – but that’s how it was and we have read about it before in such as, ‘The Grapes of Wrath’.

I mean – it bears no relation to the modern-day zero-hours gig economy, does it?

Hazel Dickens sings the title track and the eulogy at Hillard Elkins grave below