Ornette Coleman once said that “Music is not a style. It’s an idea.” Can there possibly be a better way to define the amorphous shape shifter referred to as “americana?” Often defined as “to the left of the radio dial” – which in my hometown would engage rock, pop, alternative country, traditional country, international music and most definitely jazz—the term americana means many things to many people. Because it defies categorization (circumventing the formatted, overly categorized programming of commercial radio and many record labels) it can be almost whatever you want it to be. Even music writers disagree on the size of the americana tent and just who should be excluded.

With this in mind, just what would you call a music scene that included the names below all living in one town, playing together, listening to one another, all over the short period of four years?

Eric Von Schmidt The Band John Simon

Maria Muldaur Jesse Winchester Levon Helm

Fred Neil Sonny Rollins Peter Yarrow

Bobby Charles John Sebastian Steve Madaio

Van Morrison NRBQ Henry Glover

Todd Rundgren Eric Weisberg Eric Anderson

Charles Mingus Jack DeJohnette Tim Hardin

Ed Sanders Jimi Hendrix Garth Hudson

Bob Dylan Geoff Muldaur Ben Keith

Pauline Oliveros David Sanborn NRBQ

Janis Joplin Stephen Bruton Robbie Robertson

And this is just a partial list of the residents of Woodstock, New York, from the mid-1960s to the early 1970s.

This amazing confluence of musicians was most certainly due to the presence of two early residents: Bob Dylan and his Svengali manager Albert Grossman. Both had settled in Woodstock in the 60s. Dylan had brought along the members of his back-up group who would become The Band (maybe the bell ringer of americana). Grossman, Dylan’s manager, was a powerhouse manager, handling the careers of Ian & Sylvia, Joplin, Odetta, Peter, Paul and Mary and Richie Havens among others. His presence drew many of his clients to this rural setting who in turn would attract their peers.

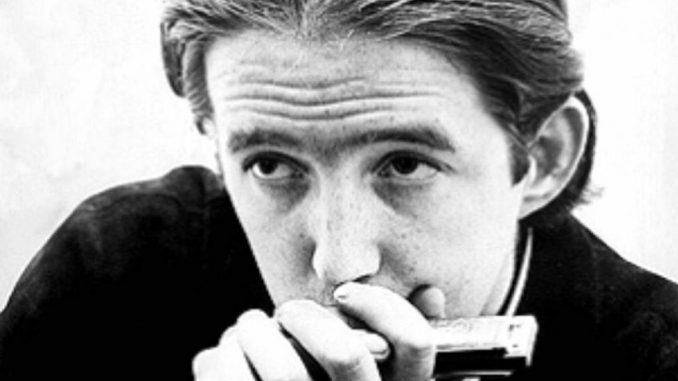

But besides Dylan one of his clients certainly played a major role in Woodstock becoming a residence or resting place for musicians from all of the styles represented by the list above: Paul Butterfield.

By the time Butterfield got to Woodstock his reputation was well-established. His integrated first band had developed a fierce reputation on the blues circuit, and it could be argued that their afternoon show at Newport in 1965, showcasing their tough, in your face, loud approach to blues standards would have more long-term impact on music than did Dylan’s plugging in at the same show (with Butterfield’s band backing him). The Butterfield Blues Band’s initial tours outside of Chicago, especially to the West Coast, would help set a course for what would become the San Francisco sound, showing them a new way to play standards, take musical chances and, after hearing ‘East West’ usher in the concept of the jam band. Butterfield and guitarist Michael Bloomfield would almost singlehandedly revive the careers of the Chicago blues greats by proselytizing for them with Bill Graham and Chet Helms of Fillmore and Avalon Ballrooms fame. They introduced a huge audience to BB King, Muddy Waters, Albert King, John Lee Hooker and others we now call icons.

But Butterfield was no blues nazi. Although he had learned the blues in the clubs of Chicago’s Southside, from Muddy, Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf and others, he had big ears and his brother had exposed him to jazz. Folk and traditional music was a mainstay in Chicago, especially at a club Grossman owned. Musically curious, Butterfield had from his second recording been moving far from the blues traditions of him hometown.

He was on a path toward something new and different. By the second album the Butterfield Blues Band was playing Eastern, modal music on ‘East-West’ an extensive, sophisticated composition that could run for 20 minutes. Also on the setlist was Cannonball Adderley’s ‘Work Song’, a jazz classic that allowed the band plenty of time for exploration and jamming. To round it out, both Allen Toussaint and Michael Nesmith (yes, that Michael Nesmith) were on the LP and part of the setlist.

The band kept morphing, adding horns/jazz players, playing extended instrumentals, as well as drawing the attention of DownBeat magazine that called out their bonafide jazz chops and big band horn arrangements. Butterfield continued to fit his harp playing into every iteration. It was this large band that would arrive in Woodstock and take residence there. This residence would mean melding with the other residents, lots of jamming at clubs like the Joyous Lake, and even assembling musicians to play jazz and even some classical music. Woodstock was a place where all of the musicians would have impact on one another. I would argue it was the birthplace of americana.

By 1970 Butterfield’s big band was nearing its end. Although still a successful touring act this nine and sometimes ten-piece ensemble, fronted by Butterfield’s vocals and powerful harp playing was no longer selling records. The band dissolved (the horn section immediately became part of Stevie Wonder’s band). The Butterfield Blues Band would be no more.

What came next is where the magic of Woodstock would come into play. The band to emerge – Better Days, would be an early example of americana before there was such a thing.

Butterfield had always surrounded himself with great musicians, and he was generous in giving everyone playing time on stage. He loved to let his guys blow, and although his was the marquee name he always positioned himself as part of the band, not its star. Better Days would continue that pattern building a new sound that crossed genres. What on paper might appear unworkable came together as something new and unique.

Guitarist Amos Garrett had been the band leader for Ian & Sylvia, a Canadian with a singular style on his instrument. Geoff Muldaur was folk music royalty and had in fact was in attendance at Butterfield’s Newport performance; he was a roots music master. Bassist Billy Rich had been gigging with Taj Mahal. Ronnie Barron had grown up in New Orleans at the feet of its keyboard royalty, as famous there as Dr. John a powerhouse singer. Chris Parker had played in Woodstock favorite Holy Moses, as well as playing drums with Tim Hardin, Bonnie Raitt and Merl Saunders.

And then there was Butterfield. After six intense years with the Blues Band, the Butter heard on the first Better Days showed he had opened up to a more ‘americana’ approach to his music. As proof here are the songwriters for the first album: Nina Simone, Eric Von Schmidt, Big Joe Williams, Bobby Charles, Percy Mayfield, Robert Johnson and Nick Gravenites. No one recording at that time put together this kind of songwriting.

Of course it’s how those songs are interpreted that’s important, and there was nothing recorded at that time that comes close to the way Better Days bounded between these disparate songs making each sound like it had been written by them. Butterfield’s harp playing – amplified and acoustic, was fresh, inventive and emotionally powerful. But it wasn’t the focus of the songs. It was the songs themselves. Barron and Muldaur shared lead vocals with him, Garrett’s liquid guitar floated over a locked in rhythm section. An arrangement for five horns might appear (featuring Dave Sanborn). Sometimes Maria Muldaur and Bobby Charles would appear singing backup or Maria would play fiddle.

It was, and still is, exceedingly fresh and surprising.

Better Day’s second recording, It All Comes Back, was more of the same. Songs by Bobby Charles, Mose Allison and Big Bill Broonzy. Not quite as striking as the first LP, but very, very close.

Luckily both are easy to locate on streaming services. And better, so is a live recording from 1973, masterfully recorded at Bill Grahams’ Winterland Ballroom. After you listen to the studio tracks check it out how the band put all of this together on stage. This recording is exactly how they sounded when I heard them – tough and gentle, loud and soft, overwhelmingly musical. With all those great songs. And those great musicians.

(There are a few other complete sets found on YouTube that further document the magic of Better Days.)

Better Days was not about a style. It was about an idea of how to interact with and portray the songs of great songwriters from different musical backgrounds. Played by six guys who also had unique, diverse musical backgrounds. And who came together in a beehive of cross-cultural music in a small town in upstate New York. I can’t think of any recording that better fits americana, before there was americana.

Thanks that’s a grand essay , I missed Paul Buterfield ,got hooked up on Bloomfield and Al Kooper probably because their albums were regulars in the cheap bins when I was a teenager. I have the 5 cd pack Butterfield original album series will give it a spin.

Thanks, Pete. That will be a good listen; see if you can find the live PBBB album and play it along with the live Better Days. A great listening experience. TE