Earlier this year I reviewed ‘Western Edge’, the first book published under a new partnership between the University of Illinois Press and The Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum. A particularly exciting aspect of this partnership is the reissuing of significant out-of-print historical works, and that starts with this excellent re-issue of a biography of DeFord Bailey, the first African American to appear at The Grand Ole Opry and a significant figure in the history of country music, reviewed here by Richard Parkinson. (Rick Bayles, Books Editor).

Earlier this year I reviewed ‘Western Edge’, the first book published under a new partnership between the University of Illinois Press and The Country Music Hall of Fame® and Museum. A particularly exciting aspect of this partnership is the reissuing of significant out-of-print historical works, and that starts with this excellent re-issue of a biography of DeFord Bailey, the first African American to appear at The Grand Ole Opry and a significant figure in the history of country music, reviewed here by Richard Parkinson. (Rick Bayles, Books Editor).

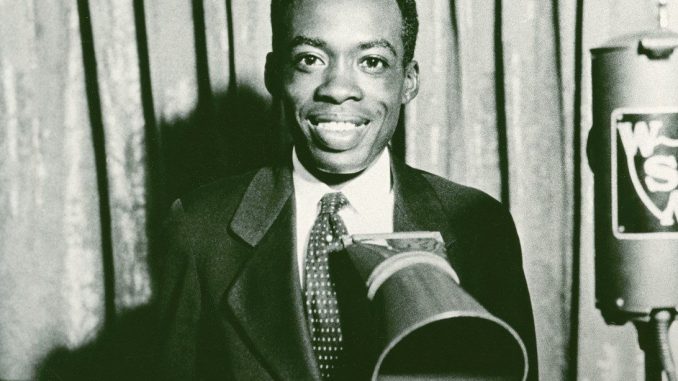

David C Morton’s biography of DeFord Bailey, originally published in 1991, begins with his memorial held on 23 June 1983, almost twelve months after Bailey’s death on 2 July 1982. In attendance, in addition to Bailey’s family, were Nashville music legends including Roy Acuff and Bill Monroe, the then Mayor of Nashville Richard Fulton, a state senator, and representatives from the Hohner Harmonica Co as well as the author, Morton. All there to celebrate the life of original Grand Ole Opry performer and harmonica virtuoso Bailey, who had been a household name from the 1920s to the early 1940s, before lapsing into relative obscurity running his shoeshine business.

Morton recounts in the introduction how he came across Bailey while he (Morton) was working in the Nashville Housing department, in one of whose public housing developments Bailey was a tenant. Initially reluctant to say much about his past, Bailey came to trust Morton with whom he had long conversations over the years. The musician would often play songs during these meetings.

Bailey’s story starts with his birth in mid-December 1899 in Smith County, TN. He lost his mother at the age of 1 and went to be cared for by his father’s sister who became his foster mother. At 3, he caught polio and while a combination of the local doctor’s efforts and his aunt’s folk remedies were able to save his life, the disease left him stunted and with a deformed back.

Bailey’s paternal grandfather, Lewis, was a virtuoso harmonica player famed throughout the region and the Baileys were a well-known musical family. Lewis taught his grandson how to play the instrument and introduced him the several tunes, including ‘Fox Chase’ and ‘John Henry’, which would form the basis of his later act. Working for a number of different families, Bailey moved to Nashville with a reputation as a fine harmonica player who would often be called upon to entertain at family gatherings and other social events.

Bailey came to wider attention through radio and a series of events which led to him first appearing on Nashville’s WDAD (he was the elevator operator at the building of the insurance company that started the station and had been invited by one of the secretaries to play at a formal executive dinner) and then on WSM. He had been brought on to the latter by Humphrey Bate and so impressed lead man George “Judge” Hay that he hired him on the spot. The show on which Bailey appeared was ‘The Barn Dance’ which, in the autumn of 1927, was renamed ‘The Grand Ole Opry’.

Bailey’s harp tunes were one of the major successes of the Opry; in particular his ‘hunt’ (‘Fox Chase’) and ‘train’ (‘Dixie Flyer Blues’ and ‘Pan American Blues’) songs. These were huge favourites with listeners. He recorded three times with Columbia in Atlanta and Brunswick in New York in the spring of 1927, and Victor in the autumn of 1928. Eleven of the eighteen tracks were released. They have been compiled on ‘Panamerican Blues’ which is available on streaming services. Morton and Wolfe also recorded Bailey performing his tunes in the mid-1970s and released them through the Tennessee Folklore Society in 1998 as ‘The Legendary DeFord Bailey’.

WSM sent its artists out on tour and Bailey was one of the biggest draws. Initially sales were poor and had to be shared out amongst the acts. Hay put Bailey on a $5 fixed fee which gave him a steady income but left him short compared to his tour mates as the takings grew. Touring in the segregated US in those decades was hard with Bailey being refused accommodation and sustenance in many places. He bore it philosophically. Sometimes his tourmates would bring him food to the car; or sneak him into hotel rooms via fire escapes. Others would refuse to stay or eat in places where Bailey had been refused. The Delmore Brothers emerge from the book with credit. Latterly, Bailey would be headlining to help the likes of Acuff and Monroe reach his greater audiences.

In May of 1941, Bailey was fired from the Opry, apparently due to the intricacies of a licensing dispute between the radio stations and the publishing companies ASACP and BMI. He set up his shoeshine business while still performing on the Opry and touring. He took it up full-time after his firing and operated very successfully until a downturn in the early 1970s, when he finally shut it down.

There was some interest in Bailey as a performer from the 1960s folk scene and he appeared occasionally on the Grand Ole Opry, usually at the request of another performer such as Acuff. Generally, though, he was inclined to turn down offers to perform or record in part, at least, as he considered he wouldn’t be paid properly. After meeting Morton, who became his unofficial manager, Bailey would play from time to time, sometimes for fellow residents of his public housing, sometimes for a wider audience. A dapper and religious man, Bailey by all accounts was self-reliant and navigated the world in which he lived effectively but quietly.

Hopefully, this reissue of Morton’s book, which features a new introduction by Dom Flemons, will encourage listeners to seek out the recordings of a superb harp player, one of the early musical giants of country music and a significant pioneer for African American musicians.

The book is available in the UK from Combined Academic Publishers.