Elijah Wald is a folk-blues musician, author and academic whose written works have focused mainly on folk and blues music. In addition to his own books, Wald co-authored Dave von Ronk’s memoir ‘The Mayor Of MacDougal Street’.

Elijah Wald is a folk-blues musician, author and academic whose written works have focused mainly on folk and blues music. In addition to his own books, Wald co-authored Dave von Ronk’s memoir ‘The Mayor Of MacDougal Street’.

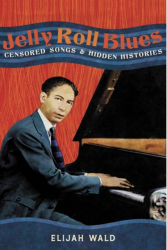

‘Jelly Roll Blues’ is sub-titled ‘Censored Songs & Hidden Histories’ and Wald’s work pretty much does what it says on the tin, highlighting aspects of the musical history of folk, blues, jazz and ragtime, especially those from within the black communities, which have been overlooked or erased in the process of popularisation of these genres over the past century and a bit.

Wald starts his narrative with an extended recording session for the Library of Congress in 1938 in which Jelly Roll Morton, egged on by Alan Lomax, lays downside after side of recordings of songs and tales of the old ‘sporting’ world in New Orleans and the American South around the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries.

One of these, ‘The Murder Ballad’, covered no less than seven 78rpm discs and lasted 30 minutes. The song is highlighted by Wald as an example of the musical tradition of creating extended songs adding narrative verses, some improvised, many recalled, celebrating the world in which they lived. Morton draws on the work of many other legendary as well as other less familiar names throughout his book.

In the days prior to the gramophone, radio and other mass media, music existed as part of a living tradition performed wherever people gathered and adapted to the environment in which it was set. Wald’s approach involves a blending of stories of particular songs, the lives of individuals and building up a picture of neighbourhoods and times from a variety of sources of evidence.

Morton sits at the hub of the narrative but its spokes extend well beyond his story. Descriptions of the red-light districts of New Orleans, St Louis and Chicago amongst others introduce the reader to a fascinating cast of characters who together, whether as composers, performers or audience members created living songs which reflected their lives and times. Wald also identifies or approximates the origins of people about whom the songs were created.

And then there is sex. The author takes the reader on a pretty detailed tour of the brothels and introduces us to the madams and sex workers who often kept male musicians with board, food and clothes. Part of Wald’s work seeks to set the context for sex work as being something widely accepted within the communities. He also contrasts the “respectable” and “sporting” worlds with a heavy overlay of the cruelty as well as the contradictions of racial segregation.

Many of the songs featured will be familiar to AUK readers: ‘Hesitation Blues’, ‘Winding Boy Blues’, ‘Staggolee’ and more as well as others that will take readers on a path of discovery. The book’s primary purpose is to highlight how central sex and bawdiness were to the songs as they grew. Much of this was lost either due to the reluctance of performers to share the racier content with the predominantly white collectors and archivists who ultimately recorded them; although Wald also explains this coming from a sense that the lyrical content was unsuitable outside the sporting environment in which they had come to be.

The book returns to the Library of Congress sessions and a period when popularisation led to a dilution of the songs’ narratives which also coincided by the annexation of copyright by the predominantly white establishment.

Overall, ‘Jelly Roll Blues’ provides a lot of information and opinion on its subject matter and is a worthwhile and enjoyable read even if the nature of the subject and the availability of resources can make its thread difficult to follow at times.