“See if you can do something with this.”

There are inconsistencies galore in the story of how events unfolded that ultimately led to Bob Dylan writing lyrics for ‘Tears of Rage’. First and foremost is disabusing the idea that Dylan wrote the song by himself. There is no doubt the lyrics came from his fertile, though fatigued at the time brain, but the melody is another matter.

Before his death, Robbie Robertson related what actually happened on a Facebook post. “When Bob Dylan typed out the words to ‘Tears of Rage,’ he handed it to Richard Manuel and said ‘See if you can do something with this.’ Richard nailed the perfect melody and chords to go with those heart-wrenching lyrics. He played it for Bob, who thought it sounded just right”.

Manuel had been noodling on the piano down in the basement of the famed Woodstock house dubbed “Big Pink”, pictured on the cover of The Band’s debut album. Upon hearing Manuel’s melody, Dylan said they should lay the track down right away. Robertson’s post continued: “We grabbed our instruments and Garth (Hudson) pressed “record” on the tape machine. Bob sang it good and we ran through it a couple of times, but Richard’s treatment and vocal made it his own. This was a breakthrough for Richard’s writing, and it set a high bar that I wanted to live up to. Rest in peace, friend”.

How that storied group of friends and musicians wound up in Woodstock is also open for discussion. The accepted explanation is they had just finished an exhausting tour in 1966 with Dylan backed by a band then known as The Hawks. By Dylan’s own account, it was to release stress and lift everyone’s spirits: “I thought I’d stay in Woodstock for a while after that tour ended, and my band came up. They liked it, too. Robbie (Robertson) called me up one day and said ‘What’s happening?’ I said, ‘Nothing.’ Well, he was in the mood for some nothing, too”.

In his first non-print interview since 2004, Dylan finally broke his silence about the 1975 double-album “The Basement Tapes”. The basement recordings were made during 1967, after Dylan had withdrawn to his Woodstock home in the aftermath of a motorcycle accident on July 29, 1966. That’s plausible except it wasn’t Dylan’s home nor was it The Band’s, which had been reported by another source. They actually rented “Big Pink”. We should assume Dylan likely paid the rent. The house, however, was in the upstate community of West Saugerties, New York, not Woodstock. The Woodstock land preserve was nearby to the South.

In other comments from unknown web sources, Dylan said that he couldn’t remember how he came to be in Woodstock. His manager, Albert Grossman, had a weekend place up there, and he persuaded Bob and Sara to move up to get away from being pestered as celebrities in Manhattan. Dylan had married Sara, a former Playboy Bunny previously known as Shirley Marlin Noznisky, in 1965. She was pregnant with the first of their four children, the last of which was Jakob, who would go on to form the Wallflowers. The couple divorced in 1977, reportedly after Dylan struck her in California. Or, it could have been his off-and-on affair with Joan Baez, or a combination of the two. Strangely, both women had parts in Renaldo and Clara, a movie which was released in 1978.

Then, we have conflicting accounts of how Dylan came to write the lyrics for ‘Tears of Rage.’ The prevailing theory is that it was a consequence of China dropping their first hydrogen bomb that raised his ire. However, Dylan soft-pedaled that idea in an interview prior to the release of “The Basement Tapes.” As he tells it: “We would just sit around upstairs with a song before going down to the basement and put it on tape. We were pretty much by ourselves in the middle ‘60s. I had nothing else to do, so I wrote a bunch of songs with pencil or typewriter. They weren’t about me. I didn’t have anything to say about myself that anybody would be interested in anyway. I looked for ideas and the TV would be on with “As the World Turns” and “Dark Shadows”. Any old thing would create a beginning to a song. These songs weren’t meant to be recorded by anybody. I just felt like writing”.

Naturally, there’s another theory out there that Dylan used the perspective of an aggrieved father trying to make sense of his daughter’s decision to reject her family, both in distance and attitude.

What does ‘Tears of Rage’ mean, Bob?

Was it seeing the news of China’s hydrogen bomb on TV? Was it a father presaging his daughter rejecting him? Or was it something Dylan scribbled on a sheet of paper because he was bored? We can undoubtedly dismiss the latter. The overwhelming majority of songs that Dylan composes are punctuated by a single line, in this case it was the chorus, one of the saddest he has ever written: “Tears of rage, tears of grief / Why must I always be the thief?”

Some critics have opined that Dylan was fed up with the world’s problems, a turn off that there was little to no hope for the future. The imagery didn’t augur well. He was throwing in the towel on humanity: “We’re so alone / and life is brief”.

Life being brief is part of a theory espoused by Sid Griffin, a renowned author, critic and musicologist, as well as the bluegrass mandolinist who is leader of The Coal Porters. He points out that a biblical theme keeps appearing throughout the song, the brevity of life a recurrent message in the “Old Testament” books ‘Psalms’ and “Isaiah’. He terms the song “as representative of community, ageless truths and the unbreakable bonds of family”.

Others contest he wrote the song out of a sense of righteous fury. This angrily composed rant took on generational trauma, social inequality, austerity’s devastating impact – and pulled it all off masterfully: “It was all very painless / When you went out to receive / All that false instruction / Which we never could believe”.

Yet another musician turned critic, Andy Gill, the guitarist who co-founded Gang of Four with Jon King, sees the hand of Shakespeare written all over the song. In particular it’s King Lear’s anguished soliloquy on the heath in the famous tragedy: “Wracked with bitterness and regret, its narrator reflects upon promises broken and truths ignored, on how greed has poisoned the well of best intentions, and how even daughters can deny their father’s wishes”. There is agreement on the father/daughter separation, but he suggests more importance should be attached to an America sharply divided over the country’s entanglement in an escalating war in Vietnam.

Greil Marcus, who was not a musician, thought the song represented a kaddish, a Jewish prayer that allows mourners at a synagogue to show their continued devotion to God despite suffering losses. The insight he ascertained is that Dylan “evokes a naming ceremony not just for a child but also for a whole nation.’With an ache in his chest, he began the song: “We carried you / in our arms / on Independence Day”‘.

As for my unscholarly notion, the troubling phrase is “be the thief.” Of what or whom? Is the father stealing from his daughter’s youth by demanding obedience? Is thieving a reference to America’s colonialist tendencies in places like Vietnam, Thailand and South America not to mention the slaves recruited from Africa or seizing Native American land? The scope is epic and so tense in the principal lines: “Tears of rage, tears of grief / Why must I always be the thief?”

Different recordings are rewarding and Richard Manuel’s chording.

As was noted at the beginning, Richard Manuel composed the music for Dylan’s lyrics. He was quoted as saying: “Bob came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper and said, ‘Have you got any music for this?’ I had a couple of musical movements that fit, so I just elaborated a bit.” Manuel’s tinkering bore strange fruit.

The song was written in the key of G major, common among songs of the day as is the basic I-VI-IV chord progression with G as the root, Em the minor 6th and C the subdominant chord creating tension before returning to the tonic. However, in the first verse Manuel adds an Am before returning to the root, which only works well with a G on top of the Am arpeggio. Unexpected but not out there. But instead of returning to the root, he brings in the F chord, again with G in the bass, something you might see in jazz or r&b. And he’s still not finished tinkering as before resolving to G, the song modulates to B major, which in theory can be done with a Bsus4 chord, though my ears aren’t picking it up.

Anyway, all these changes compelled the melody to venture into uncommon territory. Considering the standard Dylan composition, it’s highly unlikely he would have come up with this progression.

The song was initially recorded with Dylan on vocals backed The Band/Hawks. That didn’t officially see the light of day until 1975 although various bootlegs documented the session. I purchased “The Great White Wonder” during a trip to Greenwich Village in 1970 or ‘71, though “The Troubled Troubadour” was what brought me to the shop selling bootlegs out of the back room. Every LP had been sold, a bummer as I was psyched to hear unreleased tracks like ‘Million Dollar Bash’ and ‘Yay, Heavy, and a Bottle of Bread.’

The Band had already released their version, the first track on “Music from Big Pink” with Manuel and Rick Danko harmonizing the lead vocals. In their hands, the song became a gospel-tinged lament with elements of classic honky-tonk.

Joan Baez performed the song in 1968 on a TV show – ‘Playboy After Dark’ from Hugh Hefner’s mansion. There’s a video of her singing it acapella without a microphone. Everyone in the audience looks sort of puzzled, waiting for the applause sign to light up so they would know what was expected of them. If you freeze the frame at a certain time stamp, there is someone who looks a lot like Tommy Smothers in the background.

Dylan’s recording was a step back to his acoustic roots when he was releasing folk music that rummaged its way into the parts of your heart that needed it most. His voice sits atop a bedding of acoustic guitar while faint keyboards and subtle rhythms surround him. Bill Janovitz for AllMusic wrote in his review that, “He and the Band are still feeling their way through the phrasing and arrangement.”

By their recording of ‘Tears of Rage,’ The Band repaid their debt to Bob Dylan and showed they had matured enough to forge ahead on their own steam. Their musical bones had been made during Dylan’s incendiary electric tour, a record deal had been signed with Capitol, and their star that was conceived in that big, pink house in upstate New York was about to be born.

Robbie Robertson’s vital guitar combined with Garth Hudson’s subdued organ to play off Levon Helm’s purposeful drumming. They slowed the pace of the Basement recording to allow Manuel and Danko space to harmonize enthusiastically over blurts from the saxophone of John Simon. It was a mesmerizing performance and set the tone for one of the best folk-rock albums of all time. Already four of the five principals in the Band have passed, victims as the cliché goes of rock ‘n roll: “Come to me now, you know / We’re so low / And life is brief”.

By the time I got to Woodstock ….

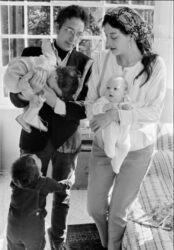

The iconic photos that illustrate this article were shot by Elliott Landy during the time Bob Dylan and The Band spent in and around Woodstock, New York in 1968 and 1969. From Landy’s account: “The first time I drove to Woodstock to photograph them, we didn’t have much time because it was Easter Sunday and they were going to Bob’s for dinner. The pond was just behind their house, which they jokingly called “Big Pink”. (West Saugerties, NY, ’68)

Besides these singular images, Landy also photographed numerous artists from the “classic” era of rock, including Janis Joplin, Van Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Joan Baez, Jim Morrison, Peter Paul & Mary, Jefferson Airplane, Santana and on and on. His photos were used on the covers of such legendary albums as “Moondance,” “Nashville Skyline” and “Cheap Thrills.” You could spend a day browsing through all the images on his website, and I heartily recommend taking that trip back in time.