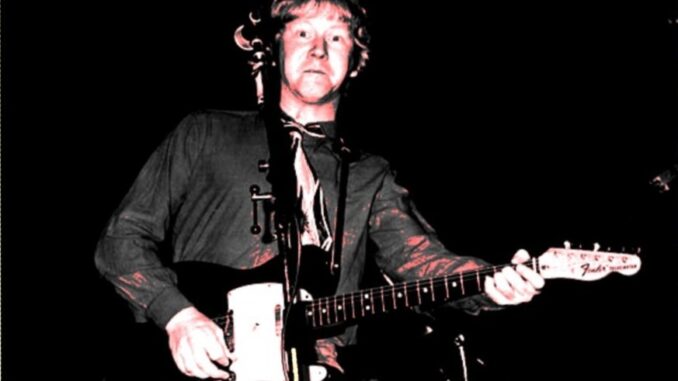

The Brinsley’s “Silver Pistol” was the album that perfected their Band obsession and, at the same time, showed that there was a lot more to them than being simple wannabes. Coincidentally, it was the first time that Ian Gomm was featured on record as singer, guitarist and songwriter, roles he continued to fulfil until Brinsley Schwarz ran out of steam in 1975. However, this was not before he wrote ‘Cruel To Be Kind’ with Nick Lowe and the Brinsleys toured with Paul McCartney. By this time, he had moved to mid-Wales, where he mixed studio work with an intermittent career that did result in a Top 20 American hit with ‘Hold On’ in the late seventies. His songs have been recorded by Glen Campbell, John Williams & Sky, Phil Everly, and Dave Edmunds. At the turn of the century, he released “Rock & Roll Heart”, which was recorded in Nashville with the help of Nanci Griffith, members of the Amazing Rhythm Aces, and Jack Clement. American artist Jeb Loy Nichols is a neighbour of Gomm in mid-Wales, and they eventually released “Only Time Will Tell” in 2010. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Ian Gomm at home in mid-Wales over Zoom to get his insider’s view of the Brinsleys and his experiences of an increasingly commercial music business. He also reminisces about the Stranglers turning up to a studio in Jet Black’s ice cream van, touring America with Dire Straits, and his unsung career in football records. Finally, Ian Gomm’s well-developed wry sense of humour is on show for all to read.

Why did you move to Wales over forty years ago?

I’ve been here for nearly fifty years, I think. I was with Brinsley Schwarz, and we were doing alright. One of our roadies, who was also with Hawkwind, who lives up the road, bought a farm with eight and a half acres for three and a half grand. When the Brinsleys split up, I was at a loose end, and I didn’t want to just hang around in London and be another saddo playing Saturday nights in pubs. I had done a five-year electrical apprenticeship with EMI when I was younger, and I got the offer to come up to mid-Wales to help turn a cow shed into a sixteen-track recording studio. So, I did all the wiring and everything, and the first group we had was the Stranglers, who turned up in an ice cream van. It was Jet Black’s ice cream business. The studio was right in the hills, near where Jeb Loy Nichols lives now, and an ice cream van came down the drive, and these lads got out, and I asked them to put the jingle on, and they did. That’s why I came to mid-Wales, and I’ve been here ever since.

It’s a very quiet place, nothing ever happens, and that’s why Jeb likes it as well. Somebody told me there is someone who lives about nine miles away who you should meet, and I used to listen to his records and think he had a good voice. Mind you, he can’t play the guitar for toffee, he has three chords and that’s that. I write songs with him and put the twiddly bits in, and when he plays live, he gets another lad in, Clovis Phillips. When he gets to the bits I played, he stops and lets Clovis do it.

Did Brinsley Schwarz ever get on Top Of The Pops back in the day?

Brinsley Schwarz turned down Top Of The Pops two or three times because they wouldn’t let us play live, and we were the first group to play live on the Old Grey Whistle Test. The bands on OGWT used to record a backing track on the Thursday before the Saturday night transmission, and if you look at the old clips, you will see that they gave the drummers rubber cymbals. I’m not kidding, because they only had a little broom cupboard at Television House, and they had four microphone channels. If you look at the old clips of say Bob Marley, there are only four mics there, so it’s not live because they are singing live and miming to the backing tracks they recorded. We said we’re not doing that, and we never turned up on the Thursday. They didn’t know what to do when we turned up with all our stuff because we used to mic our backline; we had two PAs, one for the backing and one for the vocals. In the studio, we miced everything up with our mics, and we had three vocal mics and a lead with a cannon plug on it. A BBC engineer asked what it was for, and I told him it was the backing because we mixed our own backing track and gave it to them. It was so successful that the next week, they did it live.

You joined Brinsley Schwarz for their third album, “Silver Pistol”.

They wanted another guitar player because they couldn’t reproduce on stage what they recorded in the studio. I could sing, I could play guitar, and, actually, I could write songs. My telecaster guitar is on “Despite It All” with Brinsley playing it, and I couldn’t work out whether they wanted the guitar or me to join at the time. We were all living communally in a big, big house in Northwood, which was actually the annexe of a girls’ school. That’s what you did: you’d rent a large house and turn it into five flats, and live in it. It was really good for gigging because you just got in the van to go to a gig, and when you came back, you didn’t have to drive all around London dropping everybody off, you just drove to the house and had a few more hours kip. I wrote a few songs on “Silver Pistol”, and I really enjoyed it. I must have been prolific at the time, or stoned out of my head, I don’t know. I turned up at the house for the audition, and I think I was the ninth guitarist they’d auditioned, and I just did what I did. I think it was Nick Lowe who came over and said, “Right man, you’re in.“, but what I didn’t realise the rest of them were tripping. Dave Robinson, the manager, turned up, and they told him they’d got a new member, and he was like, no, no, you’re in no state to make a decision like this, go back and do it again. I was still asked to join.

They wanted another guitar player because they couldn’t reproduce on stage what they recorded in the studio. I could sing, I could play guitar, and, actually, I could write songs. My telecaster guitar is on “Despite It All” with Brinsley playing it, and I couldn’t work out whether they wanted the guitar or me to join at the time. We were all living communally in a big, big house in Northwood, which was actually the annexe of a girls’ school. That’s what you did: you’d rent a large house and turn it into five flats, and live in it. It was really good for gigging because you just got in the van to go to a gig, and when you came back, you didn’t have to drive all around London dropping everybody off, you just drove to the house and had a few more hours kip. I wrote a few songs on “Silver Pistol”, and I really enjoyed it. I must have been prolific at the time, or stoned out of my head, I don’t know. I turned up at the house for the audition, and I think I was the ninth guitarist they’d auditioned, and I just did what I did. I think it was Nick Lowe who came over and said, “Right man, you’re in.“, but what I didn’t realise the rest of them were tripping. Dave Robinson, the manager, turned up, and they told him they’d got a new member, and he was like, no, no, you’re in no state to make a decision like this, go back and do it again. I was still asked to join.

You wrote a number of Brinsley classics, and one bona fide classic with Nick Lowe, ‘Cruel To Be Kind’.

We wrote a few more songs, but that was the best half hour Nick and I spent around the kitchen table. I told Nick at the time that it was a good one. Next time you hear it, listen to how it builds up to the hook, nearly gets there, and then turns back to build up to the hook again. That and a great hook make it such a great song. The art of songwriting, there you go. When I see people and tell them that I co-wrote it, they sing it back to me. It was featured in the recent BBC show Rain Dogs.

I hope you’re getting the royalties.

If I were Paul McCartney, I’d think there was money in this game, but it’s OK, it ticks over, but every time you think that’s it, it comes back again. It was in “Ten Things I Hate About You”, a teen romantic comedy, a few years ago. It crops up all the time. In fact, when people want to use it, the publishers have to ask for my permission, and I think American Airlines has it on their playlists on their planes. The best was “Bob’s Burgers” in America, who changed the words but kept the tune.

The definition of a classic song.

It’s OK, and if you could do it all the time, it would be marvellous. I’ve had my moments, here’s blowyourowntrumpet.com, Glen Campbell did one of my songs, Phil Everly did one, Sky with John Williams, and Dave Edmunds.

After you left The Brinsley’s, your own solo career got off to a great start in 1978 with “Gomm With The Wind/Summer Holiday” and a Top 20 US single with ‘Hold On’. What was that time like?

It’s luck. In the Brinsleys, when we weren’t in the studio and all that, I’d tune pianos to help put food on the table. I got into that because the Brinsleys had a piano that we took on the road, and it always needed tuning, and when things got a bit tough up here, I tuned pianos. All this, despite being told at school I wasn’t musical.

After a couple of years, we finished the studio we were working on and for six months, I sat in a sixteen-track studio, and no one came, so I thought I would record myself. I had got a catalogue of songs together. ‘Hold On’ was one of them, and I wrote that driving around the Welsh hills. I was singing it in the car, and I thought that’s a good little hook. I thought at the time, Why don’t I try and be a solo performer, and I started going down to London on InterCity for various appointments. The worst one I had was with this guy who was the drummer with the early Bee Gees, and he was sitting behind his desk in his office, with his cowboy boots on his desk, and I played him ‘Hold On’. The first thing I noticed was that the left-hand speaker of his stereo system wasn’t working, which took the edge off the effect of it. He said, “Let’s face it, Ian, the song sucks, and you can’t sing”, and I walked out of his office onto Oxford Street with all the buses, and thinking, is life worth living? I had the last laugh because a year and a half later, it was in the Top 20, so what did he know about anything? With most of these people, it’s about ego, and I don’t think much has changed today.

You worked with Herbie Flowers, I believe.

Yes, me and Herbie didn’t have a band, and I was on this label, Albion Records, and they said make a solo album, and that’s where I met producer Martin Rushent. They got Jeff Wayne’s session musicians, and they were on everything and were great musicians, and as Herbie said, look upon this as musical mercenaries. It was brilliant, we rehearsed for three weeks, and we only needed to rehearse for three days because we had it. It was so good. Herbie was on most of my solo albums. We got on really well, and I stayed overnight at his house once, and he had a bunk bed; he told me that Marc Bolan and David Bowie had also slept in it.

He told me once he was thinking of forming a supergroup with John Williams and other musicians he knew, and did I want to come to a John Williams party in St John’s Wood and meet them all. So we went to this party and everything was white, and there were all these pretentious people sipping wine. I said I’ve had enough of this, and we went down to the basement, and in this cellar, he had a full-size table tennis table. It was a bit like the film “Blow Up”, and there were two blonde-haired Swedish girls, and we wrote this instrumental ‘Carillion’. About nine months later, I’m sitting in the Royal Albert Hall with my wife, looking at the first Sky concert, and they played my song. That song is a test piece for brass bands; it is one of the most popular pieces at cremations and funerals. I actually phoned up the Performing Rights Society, and they said they waive the rights for funerals, and I thought, but funeral directors don’t. I played that song at my mother’s cremation and at my father’s cremation, at my daughter’s wedding, a song for all occasions.

Your last album was 2002’s “Rock’N’Roll Heart”. Why haven’t you released a follow-up?

Perhaps I’m a realist, or perhaps I’ve been through so much in my life do I really need this anymore? You put everything into it, and when nothing happens, you think, What’s the point. I laughingly say Do you think I enjoy doing this? I only do it for the money. I don’t really mean that, in fact, Jeb and I wrote a song during lockdown, called ‘Going To The Pub On Christmas Eve’. It’s brilliant, but I’m seventy-eight now, and it’s such a closed shop we had to release it as an independent digital release. The publishers and record companies have got it all stitched up; the creative people don’t mean anything to them and are just pawns in their little game. They just want the money. I said that without any bitterness at all. It’s like Shaking Stevens, who was doing really well with covers until his manager told him to write his own songs, and he did zilch. Mind you, I do remind people that ninety per cent of nothing is nothing, and ten per cent of something is worth having. Norman Petty got a co-write on Buddy Holly’s songs, and Colonel Parker took royalties from songs Elvis covered.

You put everything into it, and when nothing happens, you think, What’s the point. I laughingly say Do you think I enjoy doing this? I only do it for the money. I don’t really mean that, in fact, Jeb and I wrote a song during lockdown, called ‘Going To The Pub On Christmas Eve’. It’s brilliant, but I’m seventy-eight now, and it’s such a closed shop we had to release it as an independent digital release. The publishers and record companies have got it all stitched up; the creative people don’t mean anything to them and are just pawns in their little game. They just want the money. I said that without any bitterness at all. It’s like Shaking Stevens, who was doing really well with covers until his manager told him to write his own songs, and he did zilch. Mind you, I do remind people that ninety per cent of nothing is nothing, and ten per cent of something is worth having. Norman Petty got a co-write on Buddy Holly’s songs, and Colonel Parker took royalties from songs Elvis covered.

You had Nanci Griffith and members of the Rhythm Aces on “Rock’N’Roll Heart”, which is a very good album.

I like it. I’ve toured in America, but I had never recorded in America, and luckily, I have a couple of friends over there, and they set it up for me. We did it at Jack Clements’, who was brilliant. He liked me, and we did a week’s recording at his place, and after we left, he was asking Where’s that limey guy.

Bob Harris thinks Nashville is real, but it’s not. I went to the Grand Ole Opry with the Amazing Rhythm Aces, who finally got to play there after thirty-five years because they had previously always been blocked because they weren’t considered country enough. I was friends with their bass player, Jeff ‘Stick’ Davis, and when they went on stage, the compere was Johnny Russell, who wrote ‘Act Naturally’ which the Beatles covered, and they asked me to take some photographs from the side of the stage. They were introduced as the Rhythm Aces, and I shouted out that they are amazing. Afterwards, we were in Roy Acuff’s changing room, and he had showers and everything, and the saddest thing is you see all these musicians in their big hats, sequin jackets, and down the back they had this corridor with all these lockers. After these guys had done their show, they took all these shiny things off and put them in the lockers and put their jeans and t-shirts on. This is how false it is.

I’m sorry, I’m destroying the myth of americana now. Waitresses in restaurants sing for you at your table if they think you have anything to do with the record business. Nanci Griffith was great, and she did it for nothing, and the drummer, Pat MacInerney, was the drummer in the Blue Moon Orchestra, and Pat got her to sing on “Rock’N’Roll Heart”. I had a rock-and-roll accordion player, Joey Miskulin, and a pedal steel player came along, and they were just fantastic. I was thinking: what am I doing here? I’m out of my depth. I thought I couldn’t do better than this; that album was my lifetime dream, to record in Nashville with really good musicians.

You toured with Paul McCartney when you were in the Brinsleys.

We were on this coach to get to all the gigs in the UK, and we did two tours. Paul would be sitting at the back with Linda, and the other members of the group were drinking and gambling, and that wasn’t my style. I was wondering what I could do, and some days Paul would be sitting on his own, so I thought I’d go and have a chat with him and see if he wants to talk. We chatted for hours, just sitting and talking about anything. He was fantastic. Paul’s road manager had been saying to us that there was a real problem because Paul wouldn’t ever do Beatles songs; it would be really great if he would, because people would just love it. One night, Linda had gone to bed early in this hotel in Manchester or somewhere, and we went to this hotel room with a few bottles of whisky, and there were two guitars. I picked up one of the guitars and started doing rock and roll songs and all that. Paul picked up the other guitar, and even though he was left-handed, he could play a right-handed guitar. We played rock and roll songs for half an hour, and then his road manager gave me the wink, and I started playing ‘Love Me Do’. Paul had had a few whiskies, and he was enjoying it, when we came to the middle eight, and I realised he was looking at my fingers for the chords. After that, he started playing Beatles songs; it was like a psychological barrier.

What do you think of Cherry Red’s “Hold On: The Best of Ian Gomm” compilation, which is still available?

It’s a short album that. I know Iain McNay, who runs Cherry Red Records, and I picked all the tracks and helped them with it all. It’s there if people want it, and I think they had to repress it because it sold out; that’s because I’d bought most of them. My mother, who was Scottish, used to say, I’ll give you one thing: Ian, you are a tryer.

You’ve also released various Brinsley legacy recordings.

I’m a squirrel, and I’d kept those things for years, and then I met this guy, John Blaney, who does limited releases. We actually got the Brinsley Schwarz final album, “It’s All Over Now”, which was never released at the time, out. I was at Foel Studio in Wales, and we’d finished wiring it up and what have you, and I thought it would be great if we could get a master tape to try it out. I then thought of the unreleased album we’d recorded at Rockfield Studios, and I wondered what had happened to it. So, I rang up Kingsley Ward, whose studio it was, and he said the album was still in the tape vaults, but he was having a clear-out out and it was going to the dump. I jumped in the car and rescued them. I then remixed it all in the studio, and then contacted all the members of the group and told them I would try and get it released somewhere.

I’m a squirrel, and I’d kept those things for years, and then I met this guy, John Blaney, who does limited releases. We actually got the Brinsley Schwarz final album, “It’s All Over Now”, which was never released at the time, out. I was at Foel Studio in Wales, and we’d finished wiring it up and what have you, and I thought it would be great if we could get a master tape to try it out. I then thought of the unreleased album we’d recorded at Rockfield Studios, and I wondered what had happened to it. So, I rang up Kingsley Ward, whose studio it was, and he said the album was still in the tape vaults, but he was having a clear-out out and it was going to the dump. I jumped in the car and rescued them. I then remixed it all in the studio, and then contacted all the members of the group and told them I would try and get it released somewhere.

Nobody was interested apart from Charly Records, and I told them there were two tracks on the record that needed first-time-release permission and asked them to sort that. Of course, they never did ask them. It was Christmas Eve in this house, and a letter came through the door from the Royal Courts of Justice, and I was being sued by Charly Records. Jake Riviera, Nick Lowe’s manager, had taken an injunction out because they hadn’t asked permission for one track to be released. Charly Records had it all pressed up and ready to go, so they turned round and sued me for the costs of making it and not being able to release it. This court battle went on for three years, but luckily, I got legal aid. I had to go down to the legal chambers next to the Royal Courts of Justice, and I asked what the worst-case scenario was, and they said that I would lose the house.

I used to do football records for Cherry Red Records, and I hope you realise you are talking to Sandy Scott and Red Deville. They ended up one track short on a football supporters’ release, and I helped them out, and I eventually got it down to a fine art, making these football records. They had all the samples, the whistles and the roar of the crowd, and we were doing one about Eric Cantona in the style of the Hovis ads. It was banned from being released because it used a sample of the BBC video they made when he was playing for Leeds United, and a publisher was claiming copyright infringement. There are some real sharks in the music business, and this publisher had a musicologist ready to go to court to confirm the infringement, and they were asking for all my future royalties.

You recorded ‘Only Time Will Tell’ with Jeb Loy Nichols. How much fun was that?

That was quite a good album, that one. I think Jeb releases an album a month, or every other month. Our peak was ‘Going To The Pub On Christmas Eve’, and it’s only when you try and get things moving that you realise how tied your hands are behind your back because it’s not what you know but who you know. A lot of the time, it doesn’t even matter if the song’s shit. If you had told me when I started in school that the format for most of the UK’s music would still be two guitars, drums, and bass, you wouldn’t have been believed, because it would be assumed it would just peter out. Look at Oasis, surely they can think of something else, it just seems to be the same thing with different faces.

Our peak was ‘Going To The Pub On Christmas Eve’, and it’s only when you try and get things moving that you realise how tied your hands are behind your back because it’s not what you know but who you know. A lot of the time, it doesn’t even matter if the song’s shit. If you had told me when I started in school that the format for most of the UK’s music would still be two guitars, drums, and bass, you wouldn’t have been believed, because it would be assumed it would just peter out. Look at Oasis, surely they can think of something else, it just seems to be the same thing with different faces.

Any plans for live shows?

I often get asked about touring with Brinsley Schwarz since we are all still alive (Bob Andrews sadly died after this interview), or do I fancy doing a solo tour. I tell them the people our age don’t have roadies: we have paramedics; we are going to do a short number, and we all hope to see you at the end. I did tour with Dire Straits, their Sultans Of Swing Tour, and that was quite illuminating. It was a five-week tour of America, and we went everywhere. I unfortunately put my back out, and in Washington, DC, they took me to the hospital, and I remember going through the same doors Reagan did when he was shot. I had to pretend I was a Dire Straits roadie because we didn’t have health insurance. They took an hour to see me, and I kept telling them I was on stage at 7:30, and in the end they gave me two codeine and two Valium, and I’m not kidding, I can’t remember the gig at all. I spent most of my time lying on my back on the tour. I had a bloody good time touring when I did it, but now the thought of touring terrifies me. It is a young man’s game. Nothing’s changed, really: you get a manager who fills your head with things and keeps you working for three years, and you get some success, and after three years, you go, what’s happened, where’s the money? and the manager has run off with the money. What annoys me about the music industry is that the creative people create the music; they create what it’s all about, and yet they are at the bottom of the pile. It’s not fair.