Americana has existed all along.

For some of the most respected US newspaper titles to the specialist music press over forty years John Milward has written about all the musical strands that make up what we know as Americana. He is also the author of ‘Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll (and Rock Saved the Blues)’. Next month he publishes his second book, ‘Americanaland – Where Country & Western met Rock ’n’ Roll’. From his base in Woodstock, NY John gives AUK’s Lyndon Bolton fascinating insights into the book and his career as he digs deep into the roots of Americana.

How have you been during the pandemic? What extra burden did it put on getting a book published?

It’s actually been kind of a normal life! My wife who did the artwork for the book worked in her studio, I wrote in my office, and we both spoiled the cat and streamed way too much TV. More seriously, having a book project meant I didn’t have to hustle for other work. Like everybody else, we missed our social life, live music and theatre, and for me, playing in my band. The book was originally bought by an editor at a consortium of New England university presses who’d published my previous book, ‘Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock ’n’ Roll (and Rock Saved the Blues)’. I looked at ‘Americanaland’ as kind of a companion piece but four chapters into the book, the partnership folded. The University of Illinois Press liked those chapters, and once I assured them that I knew what I was doing, and had all the necessary footnotes, they picked it up as a work in progress.

What prompted you to undertake such a massive project?

It was similar to my motivation to write ‘Crossroads’. I found that as I get older my musical interests changed. I’ve been in two different Hudson Valley bands for the past 25 years; nothing too serious, just fun local gigs. The first, the Comfy Chair lasted a dozen or so years and the repertoire was centred on blues; the Sunburst Brothers added more country to the blues-rock mix. We play Ray Price, Steve Earle, Buddy Miller, but will still throw in some Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry. I spent 25 years writing for various newspapers and magazines covering the rock beat. But it was never just rock. In the 80’s working for USA Today I wrote profiles of George Strait and Ornette Coleman. The life of a daily newspaper critic exposes you to all different things. You’re expected to delve into a variety of subjects, so my two books are a culmination of that interest. One difference is that ‘Crossroads’ depicted a racial divide between the black blues players and the white guys they inspired. So the two worlds mixed but it was more musical than social. ‘Americanaland’ takes note of the different social attitudes of the Nashville country establishment and musicians who work under the Americana banner, but everybody loves Hank Williams. The challenge and fun of the book was discovering connections that run through it. In the first chapter you have Steve Earle commenting on Jimmie Rodgers, “Hey, he invented this gig of a guy with a guitar” and a teenaged Willie Nelson promoting a show by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys. Not to mention Johnny Cash listening to the Carter Family on the radio decades before he’d marry June Carter.

It was similar to my motivation to write ‘Crossroads’. I found that as I get older my musical interests changed. I’ve been in two different Hudson Valley bands for the past 25 years; nothing too serious, just fun local gigs. The first, the Comfy Chair lasted a dozen or so years and the repertoire was centred on blues; the Sunburst Brothers added more country to the blues-rock mix. We play Ray Price, Steve Earle, Buddy Miller, but will still throw in some Muddy Waters and Chuck Berry. I spent 25 years writing for various newspapers and magazines covering the rock beat. But it was never just rock. In the 80’s working for USA Today I wrote profiles of George Strait and Ornette Coleman. The life of a daily newspaper critic exposes you to all different things. You’re expected to delve into a variety of subjects, so my two books are a culmination of that interest. One difference is that ‘Crossroads’ depicted a racial divide between the black blues players and the white guys they inspired. So the two worlds mixed but it was more musical than social. ‘Americanaland’ takes note of the different social attitudes of the Nashville country establishment and musicians who work under the Americana banner, but everybody loves Hank Williams. The challenge and fun of the book was discovering connections that run through it. In the first chapter you have Steve Earle commenting on Jimmie Rodgers, “Hey, he invented this gig of a guy with a guitar” and a teenaged Willie Nelson promoting a show by Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys. Not to mention Johnny Cash listening to the Carter Family on the radio decades before he’d marry June Carter.

Towards the end of ‘Americanaland’s’ intro you write, “Middle age found me increasingly drawn to the roots of rock and to the best in vintage blues and country”. I thought, “he’s talking to me!” But who is your intended audience?

I am aiming at you! People who have grown up with country have seen it absorb elements of rock. Meanwhile, the rock I grew up with is now a relatively small genre within pop music. Late in the book I talk about the Drive-By Truckers. After I had left the newspaper business the free concert tickets dried up as my friends and I joked about what we called our “mid-rock crisis”. Since the newer stuff didn’t always do much for us, I started looking back more towards blues and country. I grew up on mainstream R&R and the first time I saw the Truckers was at Irving Plaza, NYC in 2004. Jason Isbell was still in the band and I was entranced. As the Truckers did their three guitars against the world thing the young guys standing next to me slapped high-fives to each other. I thought, “I’ve been there!” The Truckers would have been huge in 1975 but it’s as if they are almost out of another time now and it’s the same with a lot of Americana artists. For me, Americana represents some sort of old school aesthetic that appeals to people who grew up with rock bands, singer/songwriters, and Bob Dylan.

Have you always written about music?

After graduating from Northwestern University my first published piece appeared in the Chicago Reader, a quality giveaway that was like the ‘Village Voice’ of Chicago. Then I was hired by the Chicago Daily News where during my first week, Elvis died. So my first piece was an obit of Elvis Presley. Talk about a trial by fire! I joke that my biggest challenge was to avoid starting the obit with “the king is dead”. I lasted only nine months at the Daily News because despite its reputation as a venerable afternoon daily it was among the first of many newspapers to fold. I went freelance, moved to New York, and wrote for outlets like the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the LA Times and No Depression. It was a challenge as a freelancer has to keep the tentacles out all the time but I know from the grapevine that it’s a lot tougher these days.

After graduating from Northwestern University my first published piece appeared in the Chicago Reader, a quality giveaway that was like the ‘Village Voice’ of Chicago. Then I was hired by the Chicago Daily News where during my first week, Elvis died. So my first piece was an obit of Elvis Presley. Talk about a trial by fire! I joke that my biggest challenge was to avoid starting the obit with “the king is dead”. I lasted only nine months at the Daily News because despite its reputation as a venerable afternoon daily it was among the first of many newspapers to fold. I went freelance, moved to New York, and wrote for outlets like the New York Times, Rolling Stone, the Philadelphia Inquirer, the LA Times and No Depression. It was a challenge as a freelancer has to keep the tentacles out all the time but I know from the grapevine that it’s a lot tougher these days.

How do you define Americana? Interestingly, you refer to the way Elvis, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Everly Brothers and Carl Perkins each hit number one on all three charts; country pop and R&B.

Precisely defining Americana is so elusive as to be almost pointless. The name itself came from a radio chart as people in the 1990s such as Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, The Jayhawks, and Wilco didn’t make it onto the mainstream charts even though they were attracting the attention of smaller, adult-oriented stations. Rob Bleetstein of the radio tip sheet The Gavin Report said “Crucial Country” would be too big a slight on mainstream country but when promoter Joe Grimson suggested “Americana” they thought it was such an elastic term that it could mean almost anything. The Americana Music Association casts an extremely wide net defining Americana, but I’ve taken a narrower approach based on rock, country, bluegrass and singer/songwriters, the core of the popular music when I was growing up. Elvis, Jerry Lee, Carl Perkins, and Buddy Holly released songs that actually crossed these genres, something that happens rarely nowadays. Mainstream Nashville resented the fact that Elvis could dominate at will. But these huge hits born of blues, rock and country truly encompassed the notion of Americana. It embraced black and white, country and blues, the whole deal. The Byrds covering Dylan is also Americana, so is Willie Nelson leaving Nashville to become a Texan outlaw. In ‘Americanaland’ I try to show Americana has existed all along. It may not have a mass audience now, but it did in the 1950s.

An aspect of the book that stands out is how you constantly check back to its roots each of these strands of Americana but country is generally thought to be the most dominant. How do you view the relationship Americana has with country?

To illustrate where the mainstream country audience was back in its late1960s heyday I quote from Bill Malone’s ‘Country Music USA’ where he notes how typical country listeners appreciated its conservative values in contrast to the counterculture where the kids were growing their hair, smoking pot and protesting against the Vietnam War. Merle Haggard got caught up in the middle of that divide with his ‘Okie From Muskogee’. Dylan recorded in Nashville with country musicians but culturally he lived in a completely different world. As Clive Davis said, “All these rock acts think they can appeal to a country audience. They can’t. They don’t belong in that world”. Meanwhile, songwriters like Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt wrote songs that drew upon country but appealed to a more bohemian audience. No-one would accuse them of being from the mainstream country set!

That’s probably enough about genre defining, let’s move on to artists. Tell us how the ‘Troubadours’ of Chapter 10 turned into ‘Hard-core Troubadours’ four chapters later.

There are two different strains here. Steve Earle and Rodney Crowell were kids from Texas who ended up in Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt’s Nashville circle. These kids aspired to write songs that would stand up next to those of their new friends. Steve Earle had a couple of country hits from his ‘Guitar Town’ debut but resonated more with the rock audience. Rosanne Cash was more a west coast singer/songwriter than a typical country star, and was produced by her husband, Rodney Crowell. Her ‘King’s Record Shop’ and his ‘Diamonds and Dirt’ were brilliant country albums that spawned multiple hit singles. But none of these artists would never again connect with the country audience in quite the same way, and all made a conscious decision to not be marketed as Nashville country artists. Instead, they chose to do more personal material. Same with another troubadour, Emmylou Harris. Eventually, they all found Americana to be a more friendly, intellectually bright place for them to make adult music.

What attracted the punks to country music?

Probably mostly a desire to be a little contrary? But also a recognition of what punk had in common with the rootsy element of classic country. That said, the punks typically took a tongue in cheek approach to country. The Clash showed up to see Joe Ely rehearse after the Texan arrived in London. Ely thought they might be out to steal his gear, but then he became friends with Joe Strummer. Then they toured the US together—I caught the show in Monterey—and were surprisingly comfortable in each other’s world.

Dylan appears throughout the book. How do you begin to quantify his contribution to Americana?

Bob is huge. He is American music. People forget that before he became a folk star in the early 60s he had been playing in R&R bands. He even played piano in Bobby Vee’s band for a couple of gigs. He loved Hank and Elvis and mirrored the whole Americana genre from his early rock influences through folk, topical songs, and then turning electric. Then, after making ‘The Basement Tapes’ with what became The Band, he goes off to Nashville and records ‘John Wesley Harding’ in a week. Sure he had his dull patches but he always comes back. Look at Rolling Thunder or his wonderful early 90s blues album which seemed to set him up for a wonderful run of great albums in the past 25 years. Yet ask Bob what he’s listening to and he’ll reply, “oh, I dunno, Robert Johnson?” He doesn’t care about charts, he’s on a different scale. It’s also interesting that he and Willie Nelson have both delved into the Frank Sinatra oeuvre in later years. As far as Americana is concerned, Willie and Bob are the Great American Songbook.

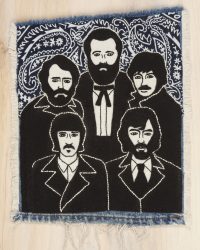

And The Band?

As good as it gets, and the essence of Americana. My YouTube moniker is ‘Whispering Pines’, partly because that’s what I see outside my window but also because it is such a lovely song. Richard Manuel just breaks your heart. But remember that they formed while playing R&B with Ronnie Hawkins, and then played rock, and later, folk and country with Dylan at Big Pink. Producer John Simon first set them up around the studio with buffers in between everybody but then thought they should all be in the centre around the mic because, “I don’t have to worry about bleeding as they don’t make mistakes”. Two anecdotes about The Band and Woodstock. I saw their debut at the Fillmore East when I was probably a junior in high school. Opening was a band called Cat Mother and the All Night Newsboys whose first album was produced by Jimi Hendrix. Thirty years later I met Larry Packer, who has played fiddle in my bands, and discovered that he was playing with Cat Mother that night at the Fillmore. I also did a No Depression profile of Levon Helm during his Midnight Ramble days. He did not want to talk to me but I thought, “fine, who needs to hear the same old gripes about Robbie?” And anyway, I had plenty of other people around Woodstock to talk to starting with Larry Campbell and Amy Helm.

As good as it gets, and the essence of Americana. My YouTube moniker is ‘Whispering Pines’, partly because that’s what I see outside my window but also because it is such a lovely song. Richard Manuel just breaks your heart. But remember that they formed while playing R&B with Ronnie Hawkins, and then played rock, and later, folk and country with Dylan at Big Pink. Producer John Simon first set them up around the studio with buffers in between everybody but then thought they should all be in the centre around the mic because, “I don’t have to worry about bleeding as they don’t make mistakes”. Two anecdotes about The Band and Woodstock. I saw their debut at the Fillmore East when I was probably a junior in high school. Opening was a band called Cat Mother and the All Night Newsboys whose first album was produced by Jimi Hendrix. Thirty years later I met Larry Packer, who has played fiddle in my bands, and discovered that he was playing with Cat Mother that night at the Fillmore. I also did a No Depression profile of Levon Helm during his Midnight Ramble days. He did not want to talk to me but I thought, “fine, who needs to hear the same old gripes about Robbie?” And anyway, I had plenty of other people around Woodstock to talk to starting with Larry Campbell and Amy Helm.

You must have met so many people during your career. Who was of most influence in writing ‘Americanaland’?

There are many but Buddy Miller sticks out. I was totally enraptured by Julie Miller’s ‘Broken Things’ record and had arranged to interview them for the LA Times. I saw them play the Bottom Line in New York—Larry Campbell was in the band– but they were on a tight schedule, so I ended up meeting them for an interview at Newark Airport before they flew back to Nashville. We had a great talk and as time went on couldn’t help but notice just how integral Buddy had become in so many Americana projects, from playing with Emmylou Harris, touring with Robert Plant with Alison Krauss, being in Plant’s Band of Joy with Patti Griffin, collaborating with Jim Lauderdale and producing a host of great albums. Buddy’s network was wide and went back to 1980 in New York when he formed the Buddy Miller Band with Julie and Larry Campbell. Then when Julie left the Buddy Miller Band for Jesus, he recruited somebody he knew from Austin, Shawn Colvin. When Buddy left NY to reunite with Julie, Shawn recruited John Leventhal to play guitar. He ended up producing her debut album, ‘Steady On’, and later married and made records with Rosanne Cash. In that sense, ‘Americanaland’ can seem like something of a small town.

Might some readers be surprised to see The Beatles pop up in a history of Americana?

Maybe, but they did covers of Carl Perkins and don’t forget when they went to Hamburg they played long club sets of American music. Ringo typically sang the country tunes like Buck Owens’ ‘Act Naturally’, but the Beatles owed plenty to Buddy Holly and Lennon was certainly influenced by Dylan. They might not have employed steel guitars, but songs like ‘I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party’ suggest that Lennon and McCartney learned a lot from the country music. And vice versa: Buck Owens and the Buckeroos did a Beatles medley in their show. His audience would go, “what are you doing?” So Buck had to publicly pledge to play only country songs. Turned out it’s much easier for rock and rollers to meddle with country than for country players to fool around with rock and roll.

You also mention Richard Thompson and Fairport Convention but would you point to any other UK influences?

Well, Brinsley Schwartz certainly reflected 1970s country rock, and then Nick Lowe briefly married into country royalty. Plus Britain’s influential acoustic folk scene of the 1960s; more recently you had Billy Bragg and Wilco writing new songs using old Woody Guthrie lyrics. But frankly, you’d probably do much better at answering that question!

How do you see the future of Americana, especially post-pandemic?

That’s what we are all wondering. During lockdown we watched a DVD of U2 at the Rose Bowl and I thought that perhaps those massive, expensive totally impersonal experiences don’t really need to come back. Lockdown has perhaps made us more attuned to the more intimate music of artists like Brandi Carlile, Sarah Jarosz and I’m With Her. Because in the end, Americana is about good songs and working musicians, not huge stars.

AUK readers are always interested in what people are listening to. What’s on your playlist just now?

I listen to a bit of everything including jazz and classical. For some reason, recent favourites are mostly women: Sarah Jarosz, Taylor Swift, Aoife O’Donovan, Brandy Clark, and Kacey Musgraves. And you won’t be surprised that I’ve been cranking up the new Drive-By Truckers live album from 2006 ‘Live@Plan 9’. When I was an active critic I used to love coming home to see what had arrived in the mail. Now I peruse the new releases on Spotify.

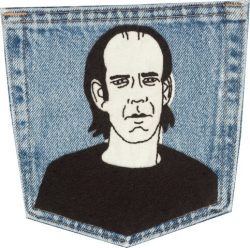

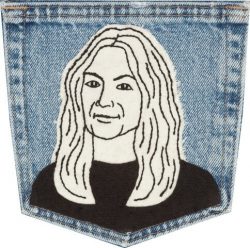

Throughout the book there are lovely portraits of some of the big names. How were they made?

My wife Margie Greve did these. Margie has a long history of creating woodcuts, and her work typically accentuates the contrast between dark and light. She did digital portraits for ‘Crossroads’ and scanned fabrics into the pictures. Since Americana can be kind of homespun, she put her sewing skills to work and created these new portraits using fabric and embroidery floss. They took a long time so that’s how she spent the pandemic, but it was worth it when the University of Illinois Press decided to give each portrait a full page.

My wife Margie Greve did these. Margie has a long history of creating woodcuts, and her work typically accentuates the contrast between dark and light. She did digital portraits for ‘Crossroads’ and scanned fabrics into the pictures. Since Americana can be kind of homespun, she put her sewing skills to work and created these new portraits using fabric and embroidery floss. They took a long time so that’s how she spent the pandemic, but it was worth it when the University of Illinois Press decided to give each portrait a full page.

You also have an accompanying ‘Americanaland’ podcast and playlist?

Yes, one each for each chapter. I got an email from the marketing director of UoI Press to say that he was afraid these might cut sales of the book. Perish the thought! But the podcasts are just a sketch of the subject matter, thought from now on, there’ll only be one a month. These and more extensive playlists for each of the seventeen chapters are on Spotify.

Nice article Lyndon – wonder if the book will come our way to review?

Thanks very much. I think the book review is imminent.

Great interview. I’m looking forward to the book and to listening to the podcasts and playlists!