Re-releasing 22 albums is just a way to keep working and playing.

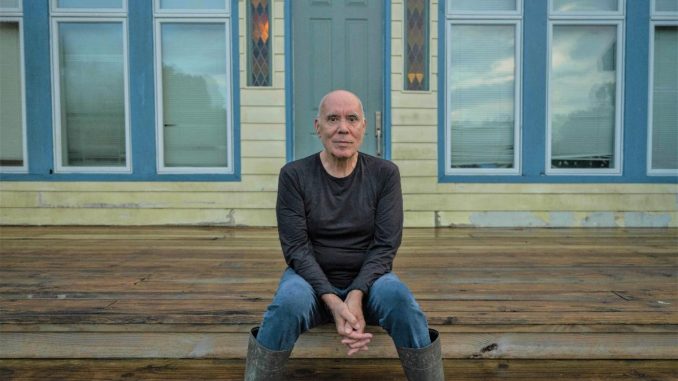

The ‘60s still exerts a significant influence over music for a whole variety of reasons, and one key characteristic of ‘60s music was that for a while, anything was possible. Musicians felt free to try new musical ideas and mix and match across genres to develop their own musical identity. This freedom was largely lost as the music industry gained more control during the seventies with music and musicians being increasingly put into particular boxes. One musician come producer engineer has built a lifetime career on maintaining the ‘60s ideal of trying to create new music and ignoring genres. Mark Bingham has had a deal with Elektra and Warner Brothers Records, lived and worked in Los Angeles, New York, and New Orleans, and worked with everyone from Hal Willner, Dr. John, R.E.M., and Marianne Faithfull to jazzers John Scofield and Wycliffe Gordon, not forgetting beat poet Allen Ginsberg, through to the present day which finds him working with cajun band Michot’s Melody Makers. Louis Michot is re-releasing 22 of Bingham’s records on his own Nouveau Electric Records. Americana Uk’s Martin Johnson caught up with Mark Bingham at home in Louisiana over Zoom to discuss his lifetime in music, and his working relationship with Hal Willner and Dr. John. The mammoth reissue program was also discussed, including the first two releases, the americana friendly ‘Goo Seneck’, and the more psychedelic ‘Mushroom Crowd’. Whatever his experiences and achievements in the music business, it is very clear that the original ‘60s ideal of making music for music’s sake still burns brightly within Mark Bingham.

You have had a full career, including being a musician, songwriter, producer, and engineer.

I just do stuff, and it has gone on for a very long time, haha.

Before we get into some of that detail can you explain your approach to ”chopped-up songs”?

I used to think it was possible to do something new with music, and now I don’t think that anymore. At twenty I thought I could change these chords to this country song, and it will still be a country song, but it will be cooler than all the other country songs but nah, it didn’t work out, haha. Sometimes it was as simple as writing a song on a piece of paper and then cutting the words up and putting them in a different order. And then it had something to do with rhythm and I remember opening for this band Foghat in America and I remember thinking I never want to do this, and I think they were a prototype for Spinal Tap. I love to play music, but when I was younger that wasn’t enough, I had to do something earth-shattering, mind you, that never happened, haha.

You were born in Indiana, but spent time in LA with Elektra in the ‘60s, and New York in the ‘70s before moving to New Orleans in the ‘80s, why the travelling?

It was about finding some music to do and people to hang out with. Getting a record deal when I was 17 was kind of an accident and something that wouldn’t happen today, and I think I decided early on that I didn’t want anything to do with that business, and here I am still in that business but not running errands for rock stars in Laurel Canyon like I was. It is very different from what I ended up doing with my life. I see people that knew back then who have done great and have all the money they will ever need since their twenties and they still go out and play shows, so they took that path, but I couldn’t do that path, haha. I was more about music, it wasn’t about me plus I’m just crazy. Imagine, I’m going to a lecture and I’m telling them stuff like music is pre-human beings, it exists, we just take it. The aliens brought it here, you know, haha, and this 18-year-old kid is going yeah, haha.

Why have you spent the last forty years in Louisiana and New Orleans?

My wife, now my ex-wife, was from New Orleans and I’d been in New York and the downtown music scene, No Wave, or whatever, punk rock made by people who went to prep schools, certainly different to the punk rock out of the UK. I think if you pulled all the trust funders out of CGBGs it wouldn’t have existed, haha, this wasn’t a movement coming out of the working class neighbourhoods. I got tired of New York, and I loved what was happening in New Orleans, and I was going to get a job writing for television and my wife was working in television. Then her gig got cancelled and I decided I didn’t want my gig in television, so I got a gig shucking oysters and we decided to sub-let for three months and go to New Orleans and that three months turned into forty years, haha.

How did you get together with Hal Willner, what did you learn from him?

I was his big brother, nobody knows what our relationship was in the sense I was trying to keep him out of trouble. I’ve got a Hal t-shirt on, and we did a Hal memorial show in April and it is the t-shirt from the show. Hal got a job on Saturday Night Live and that’s how we met, and at that point, Hal was trying to do a Nino Rota tribute record which he managed to complete and get out. I was trying to do a Bernard Herrmann record of the same ilk, only nobody wanted the record I was doing. I had been signed to Warner Brothers Records and I went back to them and said I’ve got this great record here, and they were like we wouldn’t sign any of those artists, why would we want a whole record of them, haha, The Lounge Lizards doing ‘North By Northwest’ and whatever, The Raybeats doing ‘The Theme From Marnie’. I started doing things with Hal, and his job was going to be what they called needle drop where you get the sketches for the show, and you would look at the sketches and try and figure out what music would go with them, and the best bit is that you would go to somewhere like Sam Goody’s with a hundred thousand LPs and every week buy a hundred records and just charge them to the TV show, and then you could keep them, haha. By the time you’d done that they had cut the sketches down, so by Friday, there would be like sixteen sketches that could make the show. So, you get all that ready, you get the music, and then by the run through there were ten and by the show, there would be eight.

It was a truly wonderful job, and Hal kept that job until he died, and it went through literally dropping needles onto vinyl, through tape onto ProTools, and beyond. Hal then gave me a chance to be on the next record, the Thelonious Monk record, and that changed everything because I did a Monk song in two minutes twenty seconds with no soloing on it, and people responded well to it so it was like maybe you can do something different. We then just kept working together and I worked with him pretty much all of the ‘80s just running around doing all kinds of stuff. I have a 35-year-old and a 32-year-old, and by the end of the ‘80s I started shifting back to staying in New Orleans, and I built a little studio, and I started working in New Orleans as a freelance record producer which is not the most stable thing in the world, and I thought it would be more fun just to record people which is what I did.

Was it as simple as you make it sound?

I’ve been good at recording since I was a kid, but I wasn’t a technical person. When I was producing records in the ‘70s I would say to the engineer let’s put the drums on five tracks and mix the tom-toms and overheads together and let’s get a balance and then bust it to two tracks, and then bust the two bass drum mikes to one. I didn’t know how to do any of that, I knew nothing. When I lived in Los Angeles, I got in a really bad car wreck because one of my jobs was driving artists home after sessions because I would suggest very few of them were capable of driving, haha. Someone running a red light smashed into me and rearranged my face, brain damage the whole works, it was pretty ugly, but in ’68 they didn’t know anything and the minute I stopped seeing bright red when I opened my eyes, they were like you are alright now, go back to living. I couldn’t remember high school and stuff like that, so it has been an interesting run after that, some people think I’ve got an incredible memory while others think I remember nothing. Living in New Orleans and dealing with the music world there, trying to write music, running around with Hal, and having a studio, it was all alright and I don’t know how simple it was, but it seemed simple to me, haha.

What was it like working with Dr. John on ‘Mercenary’?

I started working early on with Dr. John with Hal, we did a movie in 1986 and I went to Nova Scotia with Mac, and I played guitar with him, so I knew him some. My biggest humble bragging thing in music in my whole life is Mac coming over one day and asking me how Sister Rosetta Tharpe tuned her guitar. I thought that was the greatest honour, haha, and we figured it out. I learnt so much from the Mac Rebennack way of making records which was really simple, he was like you’ve got a good intro, you’ve got a verse, you have your choruses right, you have your words right, and it is in tune, and everyone is happy with the solo, it’s done. That was it, no forty-two takes, when it was done it was done because he came out of the era where the song was what made the thing work, so you get the song down and see if people like it, very simple, there was no art damage with Mac, haha. I listened to ‘Mercenary’ recently and thought it was a great record, but when it came out people were like, nah, and it just fell through the cracks. I can’t remember the label it was on, and all my life I’ve made so many records where the label goes out of business before the records came out, haha. I was also in the room when Mac recorded ‘Nawlinz: Dis Dat or d Udda’.

You are about to remedy all that with a major re-issue program for your records.

It just seemed like something to do because I want to play some more shows, and this was a way to prime the pump and get anyone to notice. You have to remember when I started out and got a record deal when I was a kid, counting all the labels in the world there were about five hundred records coming out in a year, now there are a thousand coming out every day, and anybody who can play a C Chord makes a record. So, there is a glut of music out there, much of it amazing, and much of it they should have waited, it is like eating cookie dough because you may have some nice cookie dough there with the potential to make nice cookies, but it is not cookies, haha. I’m 73 so who gives a shit, people won’t even look at someone if they are over 40, haha, that is the way the whole world works. I’ve been the older guy with no tattoos for about forty years, the drummer in our band is just 26 and I still work with young people, I’ve just worked with a 27-year-old in New York, so I don’t remember I’m 73 years old and it is not part of the equation until I catch a glance of myself in a mirror or someone calls me Sir, and I will then upset them by telling them not to call me Sir, and that I’ve got kids older than them and girlfriends younger than them, haha. So it is just about trying to get out and play some shows in the world and see if anyone shows up.

It just seemed like something to do because I want to play some more shows, and this was a way to prime the pump and get anyone to notice. You have to remember when I started out and got a record deal when I was a kid, counting all the labels in the world there were about five hundred records coming out in a year, now there are a thousand coming out every day, and anybody who can play a C Chord makes a record. So, there is a glut of music out there, much of it amazing, and much of it they should have waited, it is like eating cookie dough because you may have some nice cookie dough there with the potential to make nice cookies, but it is not cookies, haha. I’m 73 so who gives a shit, people won’t even look at someone if they are over 40, haha, that is the way the whole world works. I’ve been the older guy with no tattoos for about forty years, the drummer in our band is just 26 and I still work with young people, I’ve just worked with a 27-year-old in New York, so I don’t remember I’m 73 years old and it is not part of the equation until I catch a glance of myself in a mirror or someone calls me Sir, and I will then upset them by telling them not to call me Sir, and that I’ve got kids older than them and girlfriends younger than them, haha. So it is just about trying to get out and play some shows in the world and see if anyone shows up.

How was the release program put together, there is something like twenty-two albums aren’t there?

I had so much stuff, and if we go back to 1989 when I got my I Gig hard drive, it was the size of a suitcase and it cost $1,200, and now you can get something the size of your pinkie that you can store the Holy Koran on it, and it costs like $6. So, I had to keep changing from one format to another, upgrade Pro Tools, and transfer all the analogue stuff, and for some reason, the fact I kept having studios and moving these tapes would move with me. So, I had this stuff and a lot of it had been re-issued on other labels, and by this time none of it was on other labels, mind you there are three albums out on a label in Indiana that aren’t part of this because they are already in circulation on that label. There was also a ton of stuff I had done for film and theatre pieces and dance concerts, and various installations and all that music was there, and I started hearing it and it was good. So, I started putting it all together with a bit of editing on stuff that wouldn’t work, and I still had the older records, and it was like well let’s see what I’ve got, and that is what it ended up as, but there could be another two hours of music, but why not, editing is good.

I had so much stuff, and if we go back to 1989 when I got my I Gig hard drive, it was the size of a suitcase and it cost $1,200, and now you can get something the size of your pinkie that you can store the Holy Koran on it, and it costs like $6. So, I had to keep changing from one format to another, upgrade Pro Tools, and transfer all the analogue stuff, and for some reason, the fact I kept having studios and moving these tapes would move with me. So, I had this stuff and a lot of it had been re-issued on other labels, and by this time none of it was on other labels, mind you there are three albums out on a label in Indiana that aren’t part of this because they are already in circulation on that label. There was also a ton of stuff I had done for film and theatre pieces and dance concerts, and various installations and all that music was there, and I started hearing it and it was good. So, I started putting it all together with a bit of editing on stuff that wouldn’t work, and I still had the older records, and it was like well let’s see what I’ve got, and that is what it ended up as, but there could be another two hours of music, but why not, editing is good.

Why release 2013’s ‘Goo Senek’ and 2017’s ‘Mushroom Sound as the first two albums?

I gave Howard Wuelfing all the stuff, and he picked those two for the start, and meanwhile, I didn’t care because it absolved me of making a decision. ‘Goo Senek’ comes from ‘Gargantua and Pantagruel’, you know the giant liked to stick goose necks up his arse, so that’s where the title came from.

So you are that relaxed about the order of re-release of the albums.

Yeah, there were only four or five that were new or recent, and it didn’t seem to matter because I’ve got records I made fifty years ago coming out again, so you realise stuff is going to be there and people are going to find it, often people aren’t going to find it in the first run, some people are going to give you trouble about it, and the record coming out called ‘In The Eye’ on this other label, it’s funny I got some reviews of that which said none of these songs are good enough to have been recorded, but it has sold about 10,000 in fifty years so ten thousand people thought they were good enough.

It is your life’s work we are talking about, has the re-release program given you a new perspective on your achievements?

I just think it is something to do, and everybody needs something to do. There is no way to measure because the way things get measured in music and the arts is typically so bogus and wrong, you just try not to participate in that. On some levels putting out twenty-two records could be seen as pretentious, but it is just what I did, it is not a big deal. I think my biggest achievement is that my children are sane. Music is easy, I know how to do that, I can go over and play something on the piano, I can go bang on the drums, I can help people mix their records, those things I know how to do, but everything else is much harder. Breathing is an achievement, you know.

Tell me about playing with Michot’s Melody Makers that well-known cajun band.

It is really fun, and really it is Louis’ thing, and what I liked about the band was that we were three years in before we rehearsed. While the music is not freeform jazz, the musicians are so good we hear what is happening and follow. That is way more fun than trying to craft something for the marketplace, but people love this band, and we play a lot. We have started rehearsing and learning some 1920s cajun songs and they sound like old blues, very raggarty, the banging your foot on a barn floor kind of sound, but at the same time, it sounds ultra-modern because we are using drum pads and all kinds of electronics with it. So, one foot in the past and one foot in the future, and that makes it really fun as well, and nobody really solos except when playing the melody, it is all playing against each other, and I also really like that aspect of it. There are no guitar hero moments in it at all, not even an 8-bar solo, Charlie Parker and Mingus would approve, haha.

At AUK, we like to share music with our readers, so can you share which artists, albums or tracks are currently top three on your personal playlist?

I have to say I’ve been listening over and over to The Soul Stirrers from 1950 through 1961, so that is certainly not a modern record. I’ve also been listening to some Nigerian music, amapiano, which is kind of lilting and seems to be influenced by a lot of old American country music in a funny way, like a lot of African music was influenced by the American pedal steel music, and I love that. The big thing I’m listening to, and I’ve no idea who they are, are the many amazing people making music in Madagascar, and it sounds so much like Louisiana music, only much crazier, haha. I have to drive to a lot to go to gigs, and I turn on Radio Garden in the car and point to Madagascar and just go, wow. With a nod to Joe Boyd here, I don’t listen to much “wpse” music per se, that is white people singing English, haha.

Finally, do you want to say anything to our readers, any plans to come over to Europe and the UK?

I’m an Irish citizen now and I’ve got my EU passport, but that isn’t going to do me much good in London now is it? At some point this year I’m going to go to Ireland this year because my grandparents came from there. During the pandemic, the boring thing to do was become an Irish citizen. It will be good when I get the passport because it has always been a failsafe for the last couple of years in America, if you are travelling around not being in America might be a good thing, haha. I just want to keep going, putting out all this music is just a way of doing more, not this is it off to the museum, you know. I’m just looking forward to making more recordings, and I’m learning to play new things, so it is just an ongoing process that I’ve been doing forever. Eric Mingus and Elliot Sharp might be in the UK or France now, and they are doing this ‘Songs From A Rogue State’ stuff, and I would love to do something with those guys, they are like blues and freestyle, but it is not rap or twelve-bar blues, it is a completely different animal. So, there are still things I want to do and people I want to work with, so let’s see if it happens. I’ve got nothing to complain about, I’m not wealthy but I’ve done what I wanted to do, you get some musicians who say if I hadn’t been a heroin addict or an alcoholic, or I hadn’t gone to prison for whatever, but I don’t have any hard luck stories.

When I worked with people in the UK in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the producers had a much better attitude to music than the people in the states, very similar to Mac Rebennack, just get the music done. It wasn’t about your manager and how much advance you were getting, it wasn’t about your status or importance, it was about music, and I learned from that.