A wide-ranging account of the American hobo life by a rather forgotten man of English broadcasting.

Kenneth Allsop died in 1973 and until now he has been nothing more than a dim memory in the head of a then 17-year-old – sandwiched somewhere in between the urbanity of Cliff Michelmore and the visually wonderful Fyfe Robertson in the world of journalism and newscasting on BBC’s long gone, ‘Tonight’, programme. Allsop seemed to have one of those quintessentially English faces, memorable and yet handsomely unremarkable at the same time – hardly the face of someone who would be talking to and writing about hoboes and tramps on a 9000 mile trip around America. He was though a man of several talents, broadcaster, author, naturalist and prototype conservationist.

Kenneth Allsop died in 1973 and until now he has been nothing more than a dim memory in the head of a then 17-year-old – sandwiched somewhere in between the urbanity of Cliff Michelmore and the visually wonderful Fyfe Robertson in the world of journalism and newscasting on BBC’s long gone, ‘Tonight’, programme. Allsop seemed to have one of those quintessentially English faces, memorable and yet handsomely unremarkable at the same time – hardly the face of someone who would be talking to and writing about hoboes and tramps on a 9000 mile trip around America. He was though a man of several talents, broadcaster, author, naturalist and prototype conservationist.

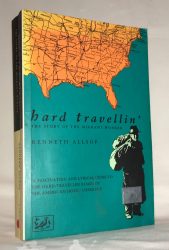

It is widely held that his death in 1973 at the age of 53, by way of a barbiturate overdose, was suicide. He had his leg amputated after a military training accident (he served in the RAF during the war) and suffered life-long pain. However, none of that held his pen in check. Wikipedia lists 16 books he wrote including Hard Travellin’, ‘The Bootleggers’, ‘The Last Voyage of the Mayflower’, and his take on the life of ‘Harriet Beecher Stowe’; broad interests but all with the central theme of America. ‘Hard Travellin; The Hobo and his History’, to give it the full title was written in 1967 – over half a century ago – and I believe it is now out of print though second-hand copies are apparently not hard to find. I have seen it described as the, ‘bumper book of bums’, and whilst that may raise a smile or an eyebrow depending on your viewpoint, there is no doubt that it is a wide-ranging, interesting volume full of information – some of which you may well question.

Allsop’s writing style can be florid and overwritten as Terry Potter correctly points out in a Letterpress Project article,

‘Sometimes I found Allsop’s prose a bit mannered and long-winded and, of course, much of it is now dated and what was then a ‘modern’ American psychology is now a historical curiosity’.

Allsop has also been accused of being something of an amateur sociologist – which by definition he was – although that does not make many of his conclusions necessarily less valid. There is, and Potter agrees, a great deal to enjoy in the book with its far-ranging sweep encompassing the move west, the growth of the railways, the rise of agri-business, the heyday of Unionism and the desperate and scarcely believable methods used by the employers to maintain the status-quo so hugely in their favour. It also examines a good number of myths whilst bringing things up to date by talking to present day (well 1960’s) hobos and itinerants. Potter identifies a fundamental Allsop premise that,

‘The American hobo tradition is essentially different to the British ‘tramp’ because the hobo life is not first and foremost driven by deficit, loss or deprivation – although there are elements of all these to be found amongst the various hobo traditions’.

It is nothing revelatory that Allsop identifies two distinct groups, almost exclusively men, of those on the move. Firstly the traveller, the man with itchy feet and a desire to move on over the horizon, always with a dread of confinement. The second is the itinerant worker – and Allsop goes to some length to explain their fundamental contribution to the growth of America. He illustrates how they were both welcome and unwelcome depending pretty much what time of year it was. Another of the many threads he weaves into his narrative is the history of the wheat belt where initially small farms were the order – and the promise – of the day, only to be usurped by agri-business which initially welcomed and relied on great numbers of itinerant workers for its very existence. Gradually as machines developed and labour diminished men were less necessary and much less welcome. Allsop also identifies how this one crop agriculture benefited only a few and disadvantaged the small family farmer operating at or just above subsistence level – despite promises to the contrary for intrepid homesteaders. As was later discovered it wasn’t very good for the land either.

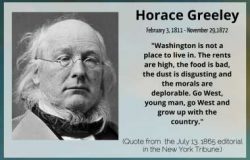

The whole westward momentum was encapsulated in the notion of ‘Manifest Destiny’ a phrase coined in 1845 by newspaperman John O’Sullivan who suggested that the United States was destined – by God, no less – to expand its dominion and spread ‘democracy’ and capitalism across the entire North American continent (or as some would currently have it – the world) regardless of who or what stood in the way. But of course, the west did not go on forever and local communities could have an ambivalent attitude to migrant workers who grew and maintained their economy so dramatically and kept it going through times good and bad.

Now, where else have we seen that happen?

One irony that Allsop points out is that these same men built the means by which their travels were achieved – the railway and the history of the hobo or travelling man are very much entwined. At various times men were welcome to ride the rails and at others, they were actively and brutally discouraged. The idea of a flexible mobile labour force, that did so much to build the American behemoth, is therefore nothing new – today it might masquerade under the title ‘transferable skills’ whilst getting ‘on your bike’ to look for work.

And yet as we know the frontier is closed, they got to the sea and inhabit everything in between and if the train started that journey it was certainly the car and the aeroplane that finished it off. Allsop contends that the hobo still represents the last vestige of wild freedom however illusory that might be – or at least that was his thought in 1967, and who is to say it is not still relevant in a film like, ‘Nomadland’, wherein the central character chooses to live the life she does. Apparently.

‘Why…. should the hobo be noticed? Yet he does enter into the anxieties and preoccupations of the others. Machine culture brought unparalleled ease of convenience to the better off American. Deliverance from frontier drudgery came, nature was whipped and overcome, but to be replaced by another wilderness, that of the apparatus of mass production, mass living, mass organisation, at the heart of which lingers the fear that something irreplaceable and unique has been extinguished’.

Rather than discuss the book cover to cover it might be illustrative to concentrate on two chapters, the first being the 10th – ‘A little Strychnine or Arsenic’ – wherein the author recounts some of the attitudes of the times which range from poisoning the hobo with the aforementioned to some surprisingly liberal arguments from the mid-western press. There are those who argue that Allsop is quotation happy and occasionally it may be true though not a view I share. It is true to say that whilst he publishes a bibliography his attributions are a bit scattershot and not always rigorously academic. He does find some good material though such as an article in the 1887 Chicago Tribune which suggested, we can only hope tongue in cheek, that,

‘The simplest plan, probably, where one is not a member of the Humane Society (or perhaps the human race?) is to put a little Strychnine or Arsenic in the meat or other supplies furnished the tramp.’

The descriptions of this heterogeneous group of people often resort to characterising them as sub-human, as in this 1876 London Times comment (and yes they were choosing to comment on things American),

‘He is a low browed, blear-eyed, dirty fellow, who has rascal stamped on every feature of his face in nature’s plainest handwriting’.

It scarcely credits that the suggestion was made in the 1878 Newburyport Herald that the problem could be solved by placing the pauper in a cistern that filled with water such that a reasonably active man could pump it out and thus not drown. If the hobo chose to work (no suggestion seems to have been made as to whether they were able) they would be able to pump and survive – if not they would die. No sign of any cruel and unusual punishments there then – as if indeed punishment was in any way merited.

It does seem that few if any of these outrageous ideas were ever put into practice – but they do reveal some of the attitudes of the times. There was little thought that the industrial system had put these men in the position in which they were found, the belief being that in fact, they were too lazy to work and that they were in some way sub-human.

Yet, thankfully, at the same time papers such as the Weekly Worker, The National Labor (sic) Tribune and the Topeka Daily Capital offered a more considered view.

‘Does it follow that every tired, ragged, footsore, dirty and hungry wretch who comes to the door to ask for something to eat is a vicious fellow?‘

You might think that the left-leaning press would say that – and that might be true. However in 1892 the Lincoln Nebraska (hardly likely to be a hotbed of radicalism), Farmers Alliance, began an article thus,

‘It is in the interest of the capitalist class to have as many men as possible out of work and seeking it in order to keep and force wages down.

The governor of Kansas, L D Lewelling issued what became known as the, ‘Tramps Charter’, in the Daily Capital, in 1893 and is remarkable enough to study in full here. Above all, it confirmed the right of Americans to walk over the land freely if they chose, that it was not the crime it was being treated as if you happened to be poor. You might well think that the constitution had guaranteed that right long ago?

This chapter then, presents a balanced account of the polarised and extreme views that hobo’s provoked – and can only ring very loud bells for our own generation as we look at how we treat the poor and disenfranchised.

Chapter 18 is entitled, ‘Sex and the Single Man’, and although it talks about heterosexuality and the presence of a limited number of female hobo’s it mainly deals with homosexuality and paedophilia. Homosexual practices were only made legal in the same year as the book was written and the author offers a very open discussion of the topic. It is only in recent years that we have semi-openly acknowledged that children can be sexually exploited in large numbers in a variety of situations where we might hope they were safe. The chapter focuses particularly on how older males would pray on younger boys, although it has to be said that it does seem to rely on a small number of first-hand accounts and a more accurate reading of the song, ‘Big Rock Candy Mountain’.

Allsop tells us that a punk, lamb or ‘preshun’ (apprentice) is a young male, many of whom were victims of what he terms a ‘white slave traffic’.

‘Avoidance of a confrontation with this common alliance in the hobo’s womanless, tentative life has usually been accomplished by either totally ignoring its existence, or by glancing references in remote Athenian terms, or by representing it as a rather touching example of the gruffly kind of wayfarer (sic) taking the greenhorn under his scrawny wing’

Harry ‘Mac’ McClintock was associated with the IWW and the song ‘The Big Rock Candy Mountain’, initially construed as the imagining of a socialist nirvana and latterly reconstructed as a child’s song (and which I and my daughter used to sing enthusiastically during car journeys). Allsop doesn’t name the lyrics but alludes to the ‘other verse’, to be found today on the Internet, that he considered too scurrilous to print. Allsop’s contention is that much of what is imagined in this song parodies the type of promises used to attract young victims in real life.

‘The punk rolled up his big blue eyes / And said to the jocker, “Sandy, / I’ve hiked and hiked and wandered too, But I ain’t seen any candy. / I’ve hiked and hiked till my feet are sore / And I’ll be damned if I hike any more / To be buggered sore like a hobo’s whore / In the Big Rock Candy Mountains.”

Allsop contends that the real surprise would be,

‘If homosexuality was not commonplace, just as it is in prisons, boarding schools and ships (no mention of the armed forces from an ex-serviceman?) in the barren and segregated loneliness of the hobo life’.

Allsop also includes Chaplin’s, ‘The Kid’ in his analysis and of Harry McClintock, he stretches his argument past the provable, when he suggests that his prowess as a troubadour made him,

‘A prize catch for the type of hobo who would indubitably have been a pop groups agent in other times and circumstances’.

Why, Tam Paton would turn in his grave!

Ultimately this wide-ranging thought-provoking book with its occasional flaws and irritations is well summed up by the blurb on the front cover,

‘It illuminates the profound dichotomy in the American attitude to the loser – and particularly towards the mobile casual worker, needed and romanticised yet hated and feared because of his non-conformism. It examines the violent antagonism towards migrants unions and also the hobo’s creation of his own legend to compensate for his rough and lonely life. Glorified by poets and lyric writers as the one surviving free man, the hobo is revealed in Mr Allsop’s fascinating portrait as being an inevitable by-product of the American system, the inhabitant of a strange and separate world. It is a harsh, turbulent and often disturbing story that Mr Allsop documents; but it is an important and extremely vivid one’.

Or, as the Kirkus review would see it,

‘The main thread of his commentary is sound: the hobo mocked the Protestant ethic, exposed the myth of universal abundance, and burlesqued the American pride in mobility so that the 19th- and 20th-century public regarded him as both an enviably happy dog and a disgusting, miserable, subversive outcast’.

There we have it then – an out of print, fifty-year-old book – bang up to date in so many ways!

Brilliant. QED.