Rotifer casts a gimlet eye on the state of the world, mixed feelings about ageing, his lost generation, and disappointment.

Although he isn’t as widely studied today, Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig was one of the most famous and celebrated European writers of the 1920s and 1930s. He and his second wife, the much younger Lotte, fled Nazi Germany in 1934 and began a peripatetic life, going from England to New York to finally, Brazil. A life in exile, even as a celebrated author who had just completed two major works, was miserable for him. It was in the city of Petrópolis, Brazil that Zweig and Lotte committed suicide together in 1942. The tragic photo of their bodies in bed, holding hands, was published all over the world.

Although he isn’t as widely studied today, Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig was one of the most famous and celebrated European writers of the 1920s and 1930s. He and his second wife, the much younger Lotte, fled Nazi Germany in 1934 and began a peripatetic life, going from England to New York to finally, Brazil. A life in exile, even as a celebrated author who had just completed two major works, was miserable for him. It was in the city of Petrópolis, Brazil that Zweig and Lotte committed suicide together in 1942. The tragic photo of their bodies in bed, holding hands, was published all over the world.

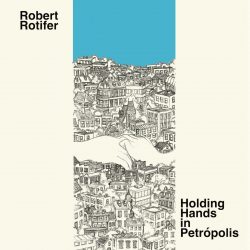

A drawing of the couple’s hands imposed on a sketch of an imaginary city is the album cover for Austrian expat singer-songwriter Robert Rotifer’s album, ‘Holding Hands In Petropolis.’ This is not a concept album about Zweig’s life, nor is it a depressing listening experience. With a folk plus classic baroque pop backing, Rotifer half-conversationally conveys his emotional states and all the thoughts that won’t leave him alone. Aside from the resigned opening song ‘He’s Not Ill,’ which is inspired by Zweig’s death and also about elderly French director Jean-Luc Godard’s assisted suicide at a Swiss clinic last year (his lawyer announced, “He had not been ill, just exhausted”), the album’s predominant subject is Rotifer’s thought-provoking musings on getting older and looking back at the past with equal parts humour and disappointment.

Along with fellow Gare Du Nord label founder Ian Button, Rotifer was joined by Fay Hallam (Primer Movers, Makin’ Time), regular collaborator Helen McCookerybook (Chefs), Kenji Kitahama (Friedrich Sunlight), and Rob Halcrow (Picturebox). Amelia Fletcher sang co-lead on the album’s sole love song (and possibly Rotifer’s only one), ‘Red Yellow Orange & Green.’ Rotifer also called on Austrian musicians Ernst Molden, “Stootsie,” and Paul Pfleger.

Both with his previous bands and during his solo career, Rotifer has always had an eye on history as it has unfolded around him. On ‘Chewing On The Bones Of The Sacred Cow,’ he appropriately excoriates the self-righteous worship of 1960s rock music, endless box sets and all. As younger generations repeatedly attempt to replicate the ‘60s, Rotifer admits “We’ve created nothing of our own.” He does this while including a Beatles-sounding guitar riff, and caustic lyrics that would do Graham Parker proud with a bewildered Paul Simon delivery.

‘That Was Our Time’ looks back at Rotifer’s youth and lefty idealism from a standpoint of political and social disillusionment. Well-intentioned badge-wearing and handing out flyers didn’t create a utopia. “That was our time and now it’s gone.” The wistful, somewhat repetitive ‘Those Dreams,’ written about recurring disturbing dreams during lockdown: “Maybe we’re so far from OK than we make out to be.” The autumnal anthem ‘Red, Yellow, Orange & Green’ sounds like sophisticated Continental ’60s pop, as does ‘Change Is In The Air.’

On ‘The Man In Sandwich Board’ the narrator steps into an elevator at a John Lewis store that turns out to be a time machine, taking him back to Oxford Street in 1984. He becomes a crazy man wearing a sandwich board and warning passersby of impending doom in the 2000s (as he says, “impending climate catastrophe and a future ruled by computer networks run by a bunch of psychopathic oligarchs”), like the ones he saw in 1984 and also ignored.

The quiet, melancholy ‘Slipped In The Rain’ brutally assesses ageing, mortality, and the resignation that we are frailer than we thought: the embarrassment of slipping and face-planting on the wet pavement while rushing to Sainsbury’s and ripping his best trousers. The brushed drums provide the sound of rain falling. The self-deprecating humour is reminiscent of Jake Thackray. Rotifer sings about making a fist to ensure that he didn’t break any bones in the fall, but I suspect there’s some anger in that gesture as well.

The dreamy arrangements and exquisite details keep the edge of these songs smooth and the bitterness at bay. Rotifer’s words may seem occasionally harsh, but his honesty is truly admirable.