This is a mighty difficult task. I was quite excited when my initial list came in at just under 100 songs. Then I thought of a few more. It feels like I should share some of my thinking about this series of articles. As writers we were asked to draw up our list of the best americana songs. The word “best” is important here. I have often thought that there is a sort of continuum in lists like this – from favourite, through best to greatest. “Favourite” feels entirely personal: quite simply the songs I enjoy or have enjoyed the most. “Best” implies some sort of intersubjectivity: songs that I like, but I think you might like too. “Greatest” has an element of objectivity: songs that have had a cultural impact and significance in the history of the genre. Calling this series of articles simply the “Top 10” has perhaps slightly obscured the task. But it does help me delve deeper, although I have tried to be mindful of not being obscure for the sake of it.

And so, to the songs. Despite this list being about the best, anyone’s list will unconsciously reveal as much about their personal musical and lyrical prejudices than anything else. There are a number of themes which feel common to americana songs. They are often about love or loss, pain and regret, the passing of time or social injustice. I will leave it to you to make any inferences about what the songs say about me. There is also considerable personal angst around songs and artists that have not made the list. Let’s face it, for every artist here there is a hundred who are not, and for all the songs on the list there was another score by the same artist jostling for position. The consolation and comfort I give myself is that on another day, different artists and songs may well have made it on.

Anyway, park the philosophy, here are the songs:

Number 10. Joni Mitchell ‘Little Green’ from “Blue” (1971)

Joni Mitchell sets the template for americana songs. This one is simple, intimate and heart-breaking. On the surface it sounds like a gentle folk lullaby, but it’s actually a veiled autobiographical confession about loss, youth and maternal love shaped by circumstance. Mitchell wrote ‘Little Green’ about the daughter she gave up for adoption in 1965, when she was young, poor and trying to survive as a musician. This was not revealed for many years, and when I found out relistening to it became both difficult and necessary. Here was a private letter of a mother bereft, disguised as poetry, accompanied by that voice – for me, one of the cleanest and most emotive voices of all time, one that just reverberates in every pore of your being – and a beautiful acoustic guitar. ‘Little Green’ is about loving someone enough to let them go – and then living with the echo of that love forever. Its power comes from what it doesn’t say – no blame, no details, no explanations. Just images, wishes and a voice trying to remain tender in the face of permanent absence.

Number 9. The Delines ‘Little Earl’ from “The Sea Drift” (2022)

Americana songs so often try to weave a story. Willy Vlautin is the master storyteller who has the gift of providing a complete narrative in just a few words. In the first two lines Vlautin establishes a tale of danger and vulnerability, “Little Earl is driving down the Gulf Coast / Sitting on a pillow so he can see the road”. Lines that are spare, concrete and devastating in their restraint. The pillow becomes a symbol of premature responsibility – a fragile fix holding up a life-or-death situation. And the music sets the tone just as effectively: beautiful, yet sinking – with Amy Boone’s intimate, lush, yet world-worn voice, some wonderful strings, keyboards and a trumpet that echoes the tragedy of Little Earl. And there is no release, no lesson, no ending offered. We are left where Earl is: inside the car, in the heat, afraid to stop and afraid not to.

Number 8. William Prince ‘The Spark’ from “Reliever” (2020)

Probably the first thing that hits you when listening to William Prince is his voice: such a rich, wonderful baritone that you might want to be hugged by it for ever. And here is Prince at his most warm and achingly romantic. ‘The Spark’ is a song about intimacy that doesn’t deny risk. Rather than treating love as rescue or certainty, it is framed as a shared exposure – something warming and dangerous at the same time, made survivable only through mutual presence and honesty. A recurring tension runs through the song – “You always think I’m leavin’/Before I’ve had the chance to stay” – of the fear of abandonment and the fear of staying. Fire is the song’s central metaphor, but it’s handled with unusual care. Fire here is not rage or catastrophe; it’s closeness, passion, vulnerability – “Don’t be afraid of the fire, babe / I’d never let you burn”. And this allows the final line, the twist, to have great impact.

Number 7. Lucinda Williams ‘Real Live Bleeding Fingers and Broken Strings’ from “World Without Tears” (2003)

Can a song be so brilliant because of its imperfections? ‘Real Live Bleeding Fingers and Broken Strings’ is Lucinda Williams at her most unguarded, writing about artistic devotion as something physical, obsessive and damaging. The song isn’t simply about loving an artist or a lover; it’s about loving the cost of creation – the wounds, excesses and compulsions that make the work feel alive. It was written during a period in which Williams was listening obsessively to the work of another musician, Paul Westerberg. He is described as “Prince Charming”, but this is pointedly ironic. He is not a fairy-tale figure, but someone “raw and exposed”, dressed not in fantasy but a much darker reality of “heroin” and “Real Live Bleeding Fingers” – the clear cost of being an artist. And musically the song feels deliberately underproduced: laid back, loose, lo-fi and such a perfect match for the tone of the song – artistic pain is not dressed up by musical embellishment, it is just met with a rawness of voice and guitars.

Number 6. Birds of Chicago ‘Love in Wartime’ from “Love in Wartime” (2018)

Some songs stay with you because of the power of the words and the music. This is one of them. JT Nero and Allison Russell are in perfect harmony on this song. ‘Love in Wartime’ is a song embedded in the ordinary, with power coming from contrast: tenderness set against instability, domestic ritual held up against a threatening world. Musically, the close harmonies reinforce the song’s emotional basis – love survives not by overpowering chaos, but by braiding voices together inside it. And there is a magically emotive guitar part that just aches with a sense of everyday struggle. The chorus gives the song its title and its tension – “This is our love / Love in wartime”. “Wartime” is never specified. It could be political, social, emotional or all three. The ambiguity feels deliberate. What matters is that love is occurring despite conditions that should make it fragile. The images that follow sharpen the contrast – “White flower / In the red sky” – purity against threat. The song’s beauty lies in its restraint. No grand declarations, no promises of safety – just two people waking up, making coffee, feeding a child, noticing the light and singing together. And the performance is just so beautiful.

Number 5. Carrie Elkin and Danny Schmidt ‘Company of Friends’ from “For Keeps” (2014)

‘Company of Friends’ is a Danny Schmidt song which appeared on his 2008 album “Little Grey Sheep”. However, I think this version – from “For Keeps”, an album on which Elkin and Schmidt sing each other’s songs – raises the song to something even more special. Musically, it remains a simple, anthemic number but Elkin’s voice seems to bring an intimacy and immediacy to it. ‘Company of Friends’ is a song which I hope will be played at my funeral, although its message is not funereal. This is a reflective yet celebratory number which has the powerful existential challenge to think about death in order to think about the now. The song suggests a quiet manifesto of how to measure a life: not by what we might have achieved or accumulated, but by the people we have around us – the shared acts of care, work and wonder that make up who we are. And there’s such joy here too: the acts that are celebrated, the things that are believed in, are small (“red balloons”), intimate (“lips on ears”) and fallible (“being wrong”). And the conclusion – “I believe in living smitten / I believe all hearts will mend / I believe our book is written / By our company of friends” – through its simple hope, never fails to bring a tear to my eye.

Number 4. Jason Isbell and the 400 Unit ‘If We Were Vampires’ from “The Nashville Sound” (2017)

‘If We Were Vampires’ is a lyrically brilliant concept from one of americana’s greatest artists: it is an imagination of what love and life would be like if we were immortal. All of a sudden the mammalian need to cling to another disappears; the physical markers of attraction are no longer necessary. The song’s beginning makes this clear, “It’s not the long flowing dress that you’re in / Or the light coming off of your skin”. This ingenious twist on the traditional love song does then reveal what is important – the clear-eyed acceptance of impermanence. Isbell’s achievement here is restraint: the song never raises its voice, never reaches for grand metaphor beyond the one in its title. Instead, it lets mortality quietly reshape what love means. The heart of the song arrives with a blunt admission – “It’s knowing that this can’t go on forever”. There’s no poetry softening this line. Its power comes from its plainness. Love is framed not as escape from time, but as something sharpened by it. And then the prayer-like “Maybe we’ll get forty years together”; forty years sounds generous – until it doesn’t. And then the devastating understatement of “And hope it isn’t me who’s left behind”. The music perfectly matches the mood of the song: on the surface it appears to be just a beautiful acoustic guitar and Isbell’s brilliant, plaintive vocal. And then you notice more. Amanda Shires’ voice in the background is subtle and adds depth to Isbell’s voice – but also feels slightly distant, like the vampires in the song. And there are some mournful strings and a sound like the wind even further in the background – a sense of the foreshadowing of death. Ultimately, ‘If We Were Vampires’ suggests that love’s value comes not from permanence, but from awareness. Knowing that time is limited doesn’t weaken commitment, it intensifies it. Mortality becomes the reason to hold on, not the reason to look away.

Number 3. Tracy Chapman ‘Baby Can I Hold You’ from “Tracy Chapman” (1988)

I was brought up on albums and remain a fan of the form. Context of a song is therefore important. ‘Baby Can I Hold You’ follows a powerful and disturbing song about domestic violence, which is sung a cappella, so the first click of percussion, the first guitar chord hit you like a sensual, sonic wave – and create a moment of catharsis. The song has its own power too: it is beautifully crafted and is built around the smallest possible vocabulary – so, mirroring the message of the song, which is about how devastating withholding words can be. Chapman begins the song with one word, “Sorry”, and then shows how even this simplest form of repair remains unreachable. The refrain “Words don’t come easily” isn’t an excuse, it’s a diagnosis. The structure of the song also mirrors its subject. Lines repeat with minimal variation, creating the feeling of being stuck in the same emotional moment year after year. Nothing escalates, nothing resolves. Chapman then introduces a quiet plea, “Baby can I hold you tonight?” The uncertainty of the answer, the tentativeness of the question, the hope that sits within it, are devastating. Musically, the song showcases Chapman’s wonderfully rich and emotive voice – and the melody is beautifully composed, subtle yet compelling, and it just builds and builds. I first saw Chapman perform in a record shop in London before she was famous. I remember writing her name down in case I forgot, which now feels like an act of gross stupidity. But her music, and jaw-dropping brilliance, have remained with me ever since.

Number 2. Johnny Cash ‘Hurt’ from “American IV: The Man Comes Around” (2002)

Americana has many gateway genres. My own route into the wonders of americana was through a combination of folk and rock. ‘Hurt’ was one of the songs that opened the door and allowed me to explore, and fully appreciate, country music. In many ways ‘Hurt’ is one of the ultimate fusion records: pure americana formed by merging brilliant lyrics from a Trent Reznor industrial electronic song, sung by one of country music’s greatest singers, and produced by rock music’s most famous producer, Rick Rubin. And wow, how it works. Cash’s version of ‘Hurt’ transforms the song into a final reckoning. Where the original is inward and immediate, Cash’s version feels retrospective – a life looked at from its far edge. The cracked restraint of his voice turns self-reproach into testimony. Lines about addiction and self-destruction no longer sound confessional, they sound archival, as though the damage has already been done and carefully remembered. When Cash sings “Everyone I know goes away in the end”, it carries the weight of experience rather than fear. The imagery of power and decay – “my empire of dirt”, “this crown of thorns” – takes on biblical gravity in his mouth. Regret is not dramatised, it is accepted. And musically the song catches you a bit unawares: it begins with just Cash’s voice and an acoustic guitar, but without noticing other instruments are introduced and the song builds to a climax, which then falls off leaving Cash singing, “I would find a way”. In Cash’s hands, ‘Hurt’ becomes less a song about pain than a statement about legacy: what remains when everything else has fallen away is the truth of having felt, failed and remembered.

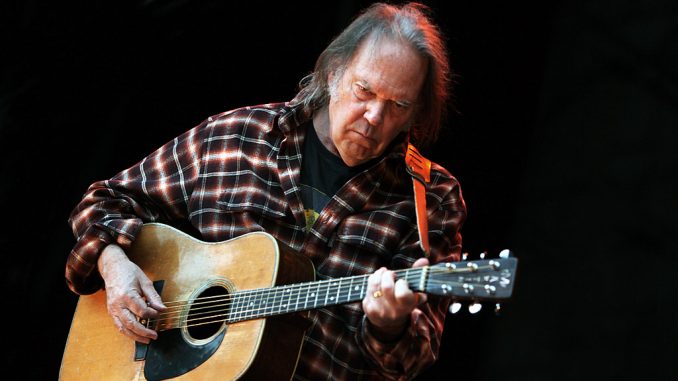

Number 1. Neil Young ‘Like a Hurricane’ from “Unplugged” (1993)

I started the list with my mother of americana; I end with my father. Neil Young is many things – godfather of grunge, folk favourite, musical pioneer. ‘Like a Hurricane’ feels like having my cake and stuffing it greedily into my mouth. Here is a song where the album version is a rock classic but here it is rendered into something beautifully americana, albeit with the brilliant twist of using a pump organ. It is also a song that’s a reminder that americana, like so many other genres, is often best served live. So many of my favourite experiences of americana are ephemeral – captured in fleeting and unique moments in venues from pubs to stadia. Fortunately, this is one that was recorded. It was also one of the first CDs I bought – yes, I was late to the format – and I just played it again, again and again. It still gets played often today. Musically, Young’s voice recaptures its absolute and enrapturing beauty of the early ’70s. The original version relies heavily on some of Young’s best guitar work, but the use of a pump organ here is inspired: all of a sudden the song is more immediate, more intimate, more affecting. There’s also a purity to the harmonica which takes this version to yet another level: it lifts the soul and seems enough to allow Young to finish this version. And the lyrics are just so powerful. ‘Like a Hurricane’ captures the moment when attraction tips into disorientation – when desire feels overwhelming not because it is chaotic, but because it is too powerful to stand inside for long – “I want to love you but I get so blown away”.