The banjo chose me.

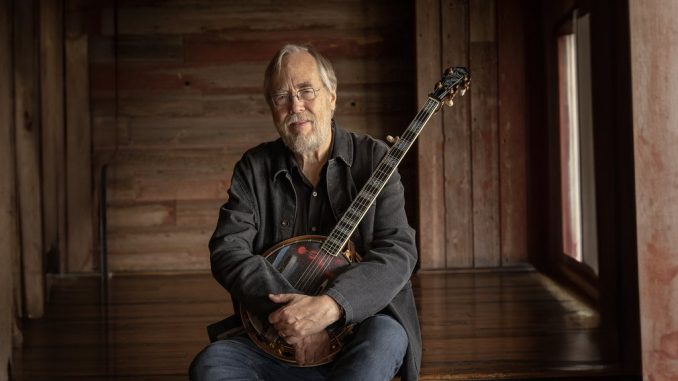

Like the iconic poster of Uncle Sam pointing a finger over the bold statement “I want you,” aimed to encourage military service during WWII, Tony Trischka declares the banjo chose him and did he ever respond. Trischka has been acknowledged as the father of modern 5-string banjo. If that’s true, then Bill Monroe must be seen as the dad for traditional bluegrass banjo, which leaves Earl Scruggs as the patriarch who erected the bridge spanning the gap from traditional to progressive.

For more than 45 years, Trischka’s stylings have inspired a whole generation of banjo players by the many layers he has extracted from the instrument’s possibilities. It all began when he heard The Kingston Trio’s recording of ‘Charlie and the MTA,’ featuring an exceptional banjo break by Dave Guard, which he offered to play during the interview. (Click on the link to hear him.) He was hooked for life and his career blasted off the starting line like Big Daddy Don Garlits firing up his “Swamp Rat” Top Fuel dragster, burning rubber down the strip, daring the vehicle not to disintegrate. In a similar way, Trischka dares his fingers to maintain control when he lets loose and plays at dazzling, breakneck speeds. Upon getting started, he quickly went from Country Cooking to Breakfast Special to three solo albums in three years (’74 to ’76) – ‘Bluegrass Light,’, ‘Heartlands’ and ‘Banjoland,” – before landing on Broadway to score the music for “The Robber Bridegroom.”

My introduction to Trischka’s music came while working at a record shop in downtown Springfield, Massachusetts. On a Tuesday, the day that the weekly shipment of stock and new albums came from the distributor, one with an unusual title caught my attention. I had this unfortunate habit of buying records by unknown artists based on the look of an album jacket or title. That’s how Bo Grumpus, Phluph, Peanut Butter Conspiracy and the like wound up alongside The Beach Boys, Santana, Janis Joplin, Wilson Pickett and The Doors in my collection.

“Robot Plane Flies Over Arkansas” was a different breed than someone raised on ‘60s rock and soul was used to (and I never got around to asking Tony how he came up with the title). Banjo was the lead instrument. I’d heard it before but not this music. Jerry Garcia played it regularly, probably on acid, and Jimmy Page dabbled with it in Led Zeppelin. The Eagles used banjo on some songs, and Jim McGuinn (before he became Roger) played both banjo and guitar with The Byrds. You could hear a taste of bluegrass from the band Seatrain when their song ’13 Questions’ played on FM radio in 1970. They were based out of Cape Cod in Massachusetts, reflected by the title of their third album, “Marblehead Messenger.” When Robot Plane came along, this style of music wasn’t completely unfamiliar.

Trischka was taking off into the bumpy skies of progressive bluegrass, an adventure which was met with the same resistance by traditionalists as every other form of evolving music did at some point. His hero was Earl Scruggs, who informed Trischka’s explosive individual style that has brought him to the pinnacle of renown. “World’s number one banjo player,” was the statement made by a reviewer in “Rude Pravda,” the national newspaper of Czechoslovakia, his ancestral homeland.

The crowning achievement of Trischka’s career is perhaps his tribute to Scruggs, embodied in the “Earl Jam” all-star album and the upcoming (2025) “Earl Jam II.” This interview delves into his career, in the fashion of going up and down the neck at various intervals from his beginnings in Syracuse, New York with “food bands playing sports rock” to when he was sent a package that contained cassette tapes of never before heard jams by Earl Scruggs and John Hartford during casual sessions at Scruggs’ home. While transcribing some of the tapes, a concept was germinating that sprouted as “Earl Jams.”

Bluegrass is every bit an American music as blues and rock, and Trischka has been at the forefront of this genre from post-Bill Monroe to modern times. Besides being a virtuoso player and composer, he runs a very successful online banjo school and has a voluminous knowledge of the instrument’s history, traced back to its roots in 19th century Africa.

It would be almost impossible to pick one particular accomplishment of from everything Tony Trischka has done in over a half-century of dedication his banjo and the music he offers to the world. A leading candidate, however, would be the two “Earl Jam” albums. You could close your eyes and envision Scruggs and Hartford sitting around heaven all day, playing another jam, then directing the chain of events that would put those singular tapes in the hands of that lucky old son, Tony Trischka.

How did you get started in music?

I started with flute lessons in elementary school, switched to piano, and then got into the folk scare, as they say, in the Sixties – The Kingston Trio, The Limelighters and groups like that. I went to the first Newport Folk Festival in 1963 and got to see Mississippi John Hurt, Bill Monroe and Doc Boggs, then the next time it was Skip James and Son House. It was an amazing opportunity to hear these great musicians at an early age.

I’ve heard that The Kingston Trio’s ‘Charlie and the MTA’ was the song at the root of it all.

The very first album I owned was “The Kingston Trio At Large,” and there’s a banjo solo in there by Dave Guard that just flipped me out. There are 16 notes in that solo that made me take up the banjo. That was it. I was hooked forever.

Did you learn that song?

If you want, I’ll play it for you right now. I transcribed all these Earl Scruggs solos and then one of my students said he wanted to learn ‘Charlie and the MTA,’ and I had never transcribed or worked up the song that made me play banjo. I finally did.

I couldn’t see your right hand. What style of picking are you using?

I’m playing TIM style or MIT going the other way: thumb, index, middle finger with finger picks.

You loved that banjo break and were determined to play banjo. How did you get started learning the instrument?

I’d been playing a little Doc Watson style guitar. So, I got Pete Seeger’s instruction book and tried learning out of that without much success. I finally found a guy named Hal Glatzer, who became my teacher. He went to Syracuse University, and at a hootenanny taught me how to play Scruggs style and other styles as well. But as I often say, the banjo chose me, that sound captivated me then and still does to this day.

Guy Clark had a line, “The song writes itself.”

Yeah, same deal.

You’ve played both guitar and banjo? The guitar has more sustain. How do you account for that on banjo?

We play more notes.

What technique helps with accelerating the speed that someone can play on banjo? Is it the roll?

In my online banjo school, I teach a lot of beginners. For some of them, it’s hard to get the speed going; their hands don’t want to do it. A metronome helps. I usually tell them play one measure, one roll, and they can usually do that really fast. And go on from there.

It’s interesting you mentioned learning piano as a youngster because sometimes in your slower passages you might think you’re hearing piano keys, kind of like thumbtacks plinking rhythmically on a hot tin roof.

Many times, when I slow things down to half-speed or quarter-speed working up an Earl Scruggs solo, it does for some reason sound like a piano to my ear. But the piano and the banjo are both percussion instruments, so there’s a similarity in the attack.

When all the counter-culture, hippie protest movement stuff of the Sixties was happening, did any of that seep into your world of bluegrass banjo?

No, no, I was totally into all that. The Mothers of Invention. Everyone came to Syracuse: Zappa, Jefferson Airplane, Hendrix, Janis Joplin. I became a big fan of the Beach Boys in Brian Wilson’s visionary period with “Pet Sounds” and many years later “Smile.” I was a big fan of Van Dyke Parks and by happenstance became friendly with him. He wrote all or most all of the lyrics on “Smile.” His album “Song Cycle” is still to this day one of my favourites. We still keep in touch with each other.

Wilson’s songs were deceptively complicated than you might get if you just listen to the finished product.

Right. And that was one of the causes of friction within the band. Also, Van Dyke Parks was writing the crazy, hard to

decipher lyrics, which I loved.

Isn’t that one of the reasons Flatt & Scruggs split, because they had a disagreement over the direction of the music? Lester liked things they way they had always been, whereas Earl wanted to move on in a more progressive direction.

I found this quote by Earl, where he said: “You can’t encore the past. When I see something shining out there, I want to move toward it.” He was a visionary. One of the last things they recorded before breaking up in 1969 was Dylan’s ‘Rainy Day Women 12 & 35.’ The hook of the song is Everybody must get stoned, and when you hear Lester singing that he sounds very uncomfortable. That was probably around the time they realized it was over.

Lester just went back home to Tennessee and carried on from there?

Yes, he called the band Nashville Grass and hooked up with Paul Warren the fiddler of the Foggy Mountain Boys and the bass player Jake Tullock as well. He was going for straight ahead traditional, and on the first album after the breakup he had a song called ‘You Can’t Tell the Boys from the Girls.’ And that says it all right there. Very contemporary saying.

Looking back at some of your early recordings, there is a term you described as “sports rock” in 1971. That’s one genre that slipped under my radar. This was the year you recorded two albums, “Country Cooking” and “Country Granola.” So, I’ll bite. What is sports rock?

You’ve never heard of sports rock? I thought everybody knew what that was. No, I was in three food bands at the same time. Breakfast Special and the other two, though since there wasn’t any such things as country granola – it was crunchy granola – that was a play on words. The leader of our band, Herbo Feuerstein, was really into sports, and he wrote a whole bunch of tunes, many of them parodies of tunes. (Tony sings to tune of “Wichita Lineman”) I am a lineman for the Giants, and I play the front line. All the various sports medleys. We were a local Syracuse band. I doubt that you can find any of those records or even songs online.

“Breakfast Special,” which came out in 1973, sounds like one of those good morning TV shows, like with Regis Philbin and Kathie Lee Gifford.

We were simply trying to think of names for the band. There was Mezzanine, and we didn’t like that, and Wreck Valley, an area North of Manhattan that had shipwrecks. We landed on Breakfast Special for no particular reason. You can name a band anything. Even now, when I sit in a diner and get the breakfast special, I think of our band. In Country Cooking, the band had two brilliant bluegrass musicians, Kenny Kosek (fiddle) and Andy Statman (mandolin). They came up from New York to record with us, and on the bus back said they should start a band with me and asked if I’d move to NYC, which was really great because I was getting tired of Syracuse. We were all into bluegrass but we would do a Hawaiian tune like, Princess Poopooly has plenty papayas, and she loves to give it away. Jewish music, Sam Cooke & The Soul Stirrers’ ‘Jesus I’ll Never Forget, all sorts of things. I played banjo and steel guitar, so in the afternoon we’d play a bluegrass festival and, in the evening, we’d get a drummer and Andy would play saxophone and we’d rock out a little bit.

Out of curiosity, what nationality is Trischka, Eastern European?

It’s basically Czech, bohemian near the Polish border. My grandfather came over from Germany and lived in Arizona doing geology. My great grandfather was from a town called Leiboric in the Czech Republic. I identify very strongly with Czechoslovakia, went there twice and had amazing tours. Actually, I was just there last fall. I have friends there, and there’s a good bluegrass scene. My wife’s family is from Napoli, so we’ve got the heavy Italian thing going on. My mother-in-law lives upstairs from us, and she still throws down when it’s time to eat. My wife’s a good cook, too, and I should weigh 500 pounds but somehow I don’t.

In the late ‘70s you were touring with Richard Greene and Peter Rowan, who I remember from Seatrain. I still have all three of their LPs in my bins.

Exactly. You’re one of the few people who know about Seatrain. I spoke to Richard a couple of years ago, and he’s doing architectural photography. You google that and he comes up. He’s not playing anymore but, of course, Peter is still at it. I used to see them with Bill Monroe in 1966, and one time our band had dinner with Bill Monroe & His Bluegrass Boys in Rochester. After dinner Monroe said: Would you like us to play for you, and we said, Yeaaah. It was the four of us in the band, and we were at the guitar player’s parents’ house. Monroe took requests for like twenty minutes in the living room. It was a life-changing event. This was Bill Monroe’s last great band. He’s had a lot of bands since, but that band was amazing.

The first record of yours I bought, “Robot Plane Flies Over Arkansas,” was by your band, Skyline. I thought ‘John’s Waltz to the Miller’ was superb. One of its more unique songs was ‘Roberto’s Dream.’

I was doing solo albums at the time and ‘Skyline’ was one of the tunes on Robot Plane. ‘Roberto’s Dream’ had more of a jazzy feel.

In the ‘90s you experimented with some African sounds on “World Turning,” a cover of the Fleetwood Mac song.

I knew that originally the banjo had come from Africa, but I went to a banjo gathering in Lebanon, Tennessee in 1990. There were guys playing from banjo instruction books in 1855. I knew there was banjo music in the late 1800’s to early 1900’s in what was called the classic style, but that was as far back as my knowledge of the banjo went. These guys were playing clawhammer style, and some of it had African roots, some of it Irish roots, and it fired my imagination as a lover of the banjo and its history. So, the album starts with an African song (‘Alfa Ya Ya’) and then it gets into tunes from the 1800’s on to classic banjo, tunes of Van Dyke Parks that he played on, old-time bluegrass then some for fans of electric. I was just trying to do the whole timeline on the album.

I was doing a story with a duo called Ordinary Elephant and learned that the style played thumb down is clawhammer. Then there’s the up-picking style, which I see in your playing.

It’s Scruggs style playing but it doesn’t have to be called that. It started in the 1800’s and was called guitar style then. It’s a fingerpicking style like classical guitar.

All this knowledge you’d accumulated and, of course, playing all sorts of styles led to the formation of your banjo school. What got that started?

It’s called Bluegrass Banjo and that’s the main thing, but it does have some fingerpicking, classical style, old-time and some Pete Seeger banjo tunes, Celtic tunes. Certain styles resonate more with some students. But I got into it in 1970. There’s an all-girl bluegrass band in Syracuse called The Buffalo Gals, and one day the banjo player asked me how much for banjo lessons. I said I don’t teach, and she said, that’s alright, I won’t pay you. And that’s how I started. They were originally called The Buffalo Chippers, but there was a festival at Carlton Horse Farm in Virginia run by Carlton Haney. He told them that’s not a good name; I’m calling you The Buffalo Gals. It stuck.

What does the school offer?

There are over three hundred lessons, from the basic how to hold the banjo to crazy progressive stuff. I use the term crazy in the best sense of the word. I have over fifty interviews with Steve Martin, Bela Fleck and all the major players. People can send in a video in what’s called the Video Exchange, and I respond to it. And then you start building a relationship with the student. Just yesterday, I responded to this player who looks like he’s ten years old, and he’s playing really great. I just did a workshop in Lansing, Michigan called the Elderly Instruments. There was a young man around 12 who came with his mother. I gave him a private lesson, which I don’t do anymore, but he’s been to Bela Fleck’s camp and is excellent. There’s a young guy, Nikolai Margulis, who is 16, and Bela Fleck has him doing some of his arrangements.

Eventually banjo players began experimenting with more progressive styles: new grass, jazzgrass, whatever it’s called. The argument became, is this still a banjo style or is it leaning towards jazz?

It depends on your definition. To me, progressive banjo is just another way of playing the banjo. If you’re playing jazz on the banjo, Louie Armstrong, bebop, Ornette Coleman or whatever, that’s jazz banjo. Bela Fleck plays bluegrass but has his own style. I took a lesson with Ornette Coleman in the ‘80s, and I had a great connection with him for that one hour and a half. But I’ve always been interested in jazz. In the ‘70s, I was playing Charlie Parker heads like ‘Donna Lee’ and ‘Ornithology.’ It’s more of the ringing style than single-line style.

I’ve been listening to your progressive music, and some of it sounds as if it’s being played with a chromatic scale, using all 12 notes of the octave. I wasn’t aware banjo used those scales very much.

It’s not uncommon. But it’s funny you should mention that because I’ve been working on using a chromatic scale all the way up the neck on all strings from the lowest to the highest note.

Even with the blending of some jazz into progressive banjo, I don’t hear anyone playing in an atonal style.

That’s because there isn’t. Although, now that I think about it, on Robot Plane there’s one tune called ‘Avondale’ which is atonal. I was listening to Schoenberg compositions when I wrote that.

I listened to an album of Bill Evans, who used to play in one of Miles Davis’ best bands, and that had sort of a jazz/bluegrass cross.

In the ‘70s, there was a banjo player by the name of Marty Cutler in New York. We talked about jazz but never did it. Bill Evans’ project was called Soul Grass, and I actually did a six-day run at the Blue Note in New York City with him. It was Sam Bush and me doing the bluegrass parts. It was an amazing experience.

Is progressive bluegrass jazz flavor a natural evolution or a conscious melding of the two?

Scruggs style is basically modern bluegrass, but people tinker like Ralph Stanley comes out of Scruggs style but puts his own spin on it. J.D. Crowe does the same. That’s what I’ve done. So, progressive bluegrass is just anything that’s outside the norm. It’s different for everybody, maybe more complex chord progressions, not better, just more complex. There’s something called the melodic style that Bill Keith has popularized, playing fiddle tunes note for note.

With the new record, “Earl’s Jam,” you have a theme similar to some others in your catalogue like “Shall We Hope,” the Civil War theme record, even “World Turning.” How did those ideas come to you?

People used to tell me you have to be goal-oriented. You need to have a plan where you want to be in five years and work towards that goal. Well, my brain doesn’t work that way. I seem to have gone along and have a fairly successful little career just by following my interests and my passions.

Who sent you the tapes?

A guy named Bob Piekiel, who lives just outside of Syracuse. He is author of “Earl’s Way” and a Scruggs family friend. Bob is also a banjo player and used to tab many of Earl’s solos in the “Banjo Newsletter.” He was at most if not all of these sessions. John Hartford recorded them all on a cheap cassette machine. One day he called Bob and said if my house burns down, I don’t want all this music to be lost, so I’ll send you copies. Bob digitized them, and then a couple of years ago when we were working on a revision of the second Earl book, he sent me a thumb drive. I was so amazed to hear all these tunes that we’d never before heard Earl Scruggs play. Some we had heard him play but not in that way. John had sent them to Bob for safekeeping, and I wanted to get them out into the world for anyone who wanted to hear.

So you, I imagine painstakingly, transcribed all 200?

No, or right now I’d be saying excuse me, I have to go transcribe. I ended up transcribing 26, 15 of which went on the “Earl Jam” album, and the other 11 will go on “Earl Jam II” which comes out next year. I’ll need another three or four tunes to fill out the album, so more transcribing to do.

On the average, about how long did it take you to transcribe one?

It would vary. John had this old cassette player, which didn’t make the best recordings, and sometimes he would string the fiddle rhythmically instead of bowing it. Strumming it would get a nice groove going, which made it easier. Then he’d get too close to the recorder making it hard to hear what Earl was playing. But if it was a tune I really wanted to capture because there was only one version of it on these tapes, I would slow it down to half speed trying to hear every single note. I’d get almost a whole measure and John would move. It wasn’t his fault; he didn’t expect anyone to ever hear them.

Hearing ‘Lady Madonna’ was fabulous, though I couldn’t find the song in Scruggs’ discography. The take on the old 1920’s hillbilly song ‘My Horses Ain’t Hungry’ is a treat. Loved ‘Dooley,’ ‘San Antonio Blues’ and ‘Little Liza Jane.’ Oh, and the bluesy take on ‘Cripple Creek’ is totally cool. There’s some foot on the gas, incredible playing by an all-star roster of players: Michael Cleveland, Sam Bush, Dudley Connell, Michael Daves, Sierra Ferrell, The Gibson Brothers, Vince Gill, Del McCoury, Bruce Molsky, Billy Strings, and Molly Tuttle. Some exceptional musicians answered your call.

Actually, they did play ‘Lady Madonna’ at least once in the Earl Scruggs Revue. If you go to YouTube, I’m sure you can find the live version. As they’re playing it on the tapes, you can hear John doing his dance, like he would on a plywood board at gigs. But here he is with Earl and there’s no audience. He just felt like dancing. I was able to recreate the dancing on the second album. But there are others that he’d never played, for example, ‘Here Comes the Bride,’ which will also be on the second album.

I’m trying to think of where I first heard ‘San Antonio Rose.’ Is it a Bob Willis tune?

That’s right. It’s his theme song. You’ll notice the sparse nature of Earl’s banjo solo. The way Earl could stack sixteenth notes is like going on a downhill with no brakes. His playing was always elegant.

I’ve never come across a horse that isn’t hungry, not even in a song written in the Depression Era.

Kelly Harrell first recorded it in 1926. It is also one of the few tracks on this album that honours its original setting – John and Earl, strictly duo. I was so glad to play this with my close friend (and one of old-time music’s greatest ambassadors), Bruce Molsky. His singing is warm and engaging, and his fiddling is smack dab in the old-time pocket with a nice touch of pizzicato

‘Dooley’ came from a Dillards’ album, “Back Porch Bluegrass.” Molly Tuttle is as terrific as usual on vocals.

I was teaching banjo at Shasta Camp in northern California. There was one banjo student, Molly, who happened to be a really good Scruggs player. I didn’t know that she sang or played guitar, but once I learned she did, I invited her to be part of my “Of a Winter’s Night” holiday show. We recorded that album at Levon Helm’s Barn in Woodstock, NY. Since then, Molly’s taken the Bluegrass and Americana worlds by storm.

If you had to pick five of the best banjo players you like to listen to, excluding yourself, who would they be?

Currently or banjo history?

Start with banjo history.

Obviously, Earl is first. Bill Keith was a huge influence on me. I became a big fan of Lamar Greer. He played from ’65 to the ‘70s. Not everyone was into his playing much, and I wasn’t either originally. But he was very plunky and had some great syncopation. He was influenced by Clarence White, one of the all-time great guitar players. There’s Don Reno, Sonny Osborne, Allen Shelton and Bobby Thompson, I’m a major fan of his. If you ever saw “Hee-Haw,” his banjo playing was all over that. Currently, Bela Fleck, of course, Noel Pikelny is really great, Kristin Scott Benson, she can play straight ahead or more progressive things, Greg Liszt of Crooked Still. He and Kristin taught at Bela’s camp. Nikolai Margulis I mentioned before and Allison Brown is amazing.

Porter Wagoner once said he considered Earl to be the Babe Ruth of bluegrass. So that must make you the Mickey Mantle.

I’d be dead if that were true, but no, I just consider myself to be good at what I do. It is an appropriate analogy because I like baseball. Bill Monroe used to travel with an exhibition baseball team in the ‘40s and ‘50s. I used to talk to Mac Wiseman about it because he was with Monroe’s team. I said to him you’ve got five bluegrass boys on a nine-person team. Where did you get the other guys? Oh, Monroe would get some guys from the Vanderbilt University baseball team to fill out the Bluegrass Boys. Those were the ringers.

I guess this effort to transcribe these jams fits the definition of a labour of love. Will there be more after “Earl II?”

It’s like doing a puzzle. It’s a lot of fun, especially when Earl does something unexpected like he often does. I thought I’d heard everything he’d do on the banjo until these recordings were in my hands. I’d hear something and say, wow, that’s strange.

Anything else in the planning stages after the two Earl Jams?

I started putting music to Emily Dickinson poems, and I’ve recorded four of them so far. Sometimes it’s just me and the singer; sometimes it’s with mandolin and bass. After that, who knows? I’ll keep on doing this as long as I can.