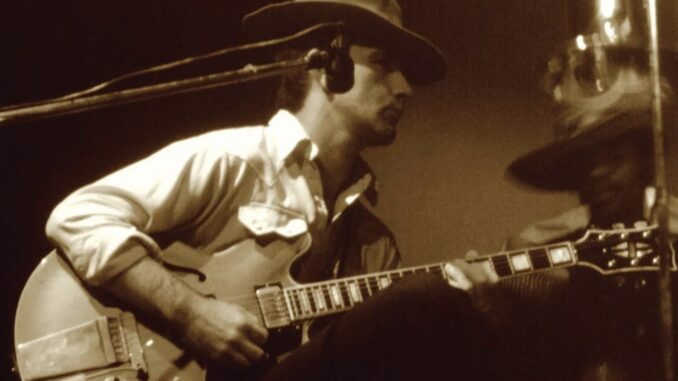

By the time Oklahoma-born singer-songwriter and guitarist J.J. Cale released his debut album in 1971, he was rapidly approaching his 33rd birthday. Along with several other young Tulsa musicians, Cale had moved to Los Angeles in the early 1960s, finding employment as a studio engineer, much of it at fellow Oklahoman Leon Russell’s studio, as well as playing the bars and clubs, gaining a regular gig at the increasingly popular ‘Whisky a Go Go’. It was whilst appearing at this club that co-owner Elmer Valentine rechristened him J.J. Cale to avoid confusion with the Velvet Underground’s multi-instrumentalist. And yet, despite almost immediately tasting success when singer Mel McDaniel scored a regional hit with his song ‘Lazy Me’, Cale found little reward as a recording artist, and not being able to make enough money as a studio engineer, sold his guitar and returned home to Tulsa in 1967. However, before leaving, he did cut a demo single for Liberty Records that a few years later would prove to be highly significant.

By the time of his death in July 2013 at the age of 74, from a heart attack, his 34-year recording career had spawned 14 albums. Though he was an artist who spurned the limelight, his musical influence has been acknowledged by such luminaries as Eric Clapton, Waylon Jennings, Neil Young, and most obviously Mark Knopfler. At the same time, his distinctive style, drawing on blues, rockabilly, country, and jazz made him one of the true originators of the ‘Tulsa Sound’, a forerunner of a genre that would eventually come to be known as americana. With that in mind, I thought this feature would offer the perfect opportunity to revisit the great man’s music, reconnect with those familiar with his songs, and hopefully help introduce him to a whole new audience.

Can’t Live With It: “#8” (1983)

After a decade of recording in Nashville, Cale had relocated to California in 1980, where he would release three albums in the space of just three years, which, having taken the best part of a decade to record his first five, was a significant change of pace, and it was beginning to tell. Audie Ashworth was still overseeing production duties as he had done since Cale’s debut album, but now more in a shared capacity with the Oklahoma songwriter. The usual group of ace session musicians were on board, including drummer Jim Keltner and keyboardist Spooner Oldham, whilst there were guest appearances from such legendary figures as guitarist Richard Thompson and pianist Glen D Hardin, which all augured well for the new release. However, at this point in his career, Cale was simply burnt out and jaded, having never been in love with the business side of the music industry, he now wanted out, and his new selection of songs reflected his mood, being at times cynical, provocative, and unremittingly grim.

Opening with ‘Money Talks’, he cuts straight to the chase with the line “you’d be surprised the friends you can buy with small change”, delivered with enough acerbic sarcasm to lacerate the narrative and leave a bitter taste. This clear dissatisfaction with life and its harsh economic woes continues through the following numbers: ‘Losers’, ‘Hard Times’, and ‘Unemployment’, that, despite the more than capable musical accompaniment, quickly becomes a hard listen with a creeping malaise of festering depression.

Much of this pessimistic vibe could be attributed to the lack of relative commercial success of his previous album “Grasshopper”, which, despite its distinctly more slick and polished production and intentionally more radio-friendly sound, had proved to be his lowest charting album to date. It’s also clear from tracks such as ‘Downtown LA’ and ‘Trouble In The City’ that Cale had become disillusioned with California’s most populous city as he bemoans the seedy underbelly of urban life. Possibly the most scathing narrative is saved for the song ‘People Lie’, where his vitriolic lyrics address the mendacity of governors, princes, preachers, and presidents, where, whatever the merits of his disdain, both the delivery and the narrative are too one-dimensional.

There are fleeting moments of brevity on songs such as ‘Takin’ Care Of Business’, but any moment of respite is short-lived when provocatively surrounded with songs such as the drug-inspired ‘Reality’ that speaks of substance abuse to escape the very problems so prolifically referenced throughout the album.

This album would be the first in Cale’s career not to make the charts in the US, and along with his mental state, “I needed a break, so I took five years off”, probably attributed to his sabbatical from the music business. The rest would prove fruitful as he would return in 1989 with the excellent “Travel-Log” that would help restore his reputation, and help to somewhat erase the memory of the ultra-negative “#8″.

The following decades would throw up the occasional oddball of an album, none stranger than the 1996 release “Guitar Man”, but for me, “#8” proved to be the most disappointing, with Cale’s negative demeanour making the album, at best, a difficult listen.

Can’t Live Without It: “Naturally” (1971)

In 1970, Cale’s musical career was languishing in obscurity, totally unaware that Eric Clapton had recorded one of the songs he had written and cut as a demo single at Liberty Records back in 1966. The song in question, which went on to be a radio hit for Clapton, was ‘After Midnight’, which most likely would have been introduced to Clapton by Delaney Bramlett, who had produced his first solo album. This breakthrough allowed Cale to record his debut album for his friend Leon Russell’s new Shelter label, formed in conjunction with Denny Cordell, who had suggested Cale take advantage of the publicity Clapton’s cover version had garnered and include the song on his own album. Cale agreed, but chose to slow this version down considerably compared to how he recorded it at Liberty Records and how Clapton would have originally heard it, with his version having imitated that original version.

Recorded at the fabled country studio ‘Bradley’s Barn’, “Naturally” saw the light of day on the 25th October 1971, and immediately showcased Cale’s smoky murmur and liquid guitar style with his own brand of country, blues, and rockabilly on the album’s opening number, the classic ‘Call Me The Breeze’, famously covered by Lynyrd Skynyrd. The song, along with a number of others on the album, featured one of the earliest models of a drum machine, Cale having always been a devoted ‘techy’, though he did later admit that he hadn’t used a real drummer due to lack of money. Nonetheless, the combination of this primitive instrument along with the unconventional blend of genres and mellow, laid-back delivery helped create a distinctive and timeless quality to his songs that set him apart from the pack of americana roots music purists.

The album also includes Cales biggest hit single ‘Crazy Mama’ that peaked at number No. 22 on the U.S. ‘Billboard Hot 100‘ chart in 1972, a position it would surely have surpassed if Cale had agreed to appear on ‘Dick Clark’s American Bandstand’ to promote the single rather than declining once he discovered he would have to lip-sync the words.

Other highlights on the album include the joyous ‘Nowhere To Run’, along with the swampy groove found on ‘Rivers Run Deep’ that evokes Tony Joe White, while the melancholic album closer ‘Crying Eyes’ is underpinned by some delightful piano playing from David Briggs, one of an elite core of Nashville studio musicians known as the Nashville Cats. Elsewhere, there are contributions from Tim Drummond and Carl Radle on bass, while legendary session musicians Buddy Spicher on fiddle and Walter Haynes on dobro all help to provide that infectious groove that emanates throughout the album.

And yet it is without doubt Cale’s laidback, subtle, and unique approach to music, cross-pollinating the genres that set this album apart, and in doing so creating a template to which he would remain true for the rest of his career. There would be other excellent albums, especially during the 1970s. However, by his own admission, his sophomore release “Reality” lacked the quality of material that had adorned his debut, stating “the first album was a collection of tunes I’d been working on for 32 years, but when it was successful the record company wanted the next album in 6 months”. Regardless of that, albums such as “Okie”, “Troubadour”, and “5” were all worthy successors, though none varied far from his by now highly recognised signature sound. Listening back, it’s hard to imagine that there would ever have been a Dire Straits without J.J. Cale.

Over the years, many critics have, unfairly in my view, labelled Cale a one-trick pony, but even if that was remotely true, it surely proved to be one hell of a trick to have.

Not very PC but I love, really love River Runs Deep on Naturally. Thanks for reminding me, off to play it now.

Hi Andy. You’re very welcome. Always happy to encourage a little bit of JJ Cale through the speakers.

Great article and I love “Naturally”, still his best album for me. Amazingly, I found my vinyl copy in a French ‘recyclerie’ for 50 cents!

Hi Rick. Glad you enjoyed the article. I’m happy with my choice, though “Troubadour” did come a close second. On another point entirely, currently putting together this month’s EPs Round-Up article and have received a very interesting one (not wanting to give away any spoilers) from the Netherlands from a band calling themselves ‘Billy & the Big Bang’. Have you heard of them?