A hugely successful, rewarding exploration of the outlying edges of rural blues and back porch folk.

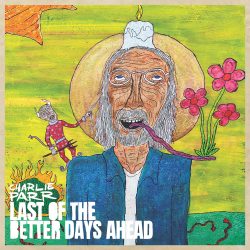

US singer-songwriter Charlie Parr’s 14th studio production, ‘Last of the Better Days Ahead’, is a rare gem of an LP, and not just because its 65 minute, double-album length is in stark contrast with the seemingly unstoppable rise of the EP in Americana.

US singer-songwriter Charlie Parr’s 14th studio production, ‘Last of the Better Days Ahead’, is a rare gem of an LP, and not just because its 65 minute, double-album length is in stark contrast with the seemingly unstoppable rise of the EP in Americana.

Now or back in the day, it’s never been that common, either, to hear minimalistic, deeply rural country and blues tunes overladen with a densely woven tapestry of free-form narratives.

But in this album at least, the intense simplicity of those two genres and the off-beat profundity of LotBDA’s most striking songs proves to be a very effective combination. And that goes for whether Parr is honing in on the sounds made by a river on the underside of a boat (“like it was knocking on a door”), the double-edged effects of memory (“Time is a game played by smarter beings”) or long-term loneliness (“I can’t remember a single name of my neighbours or the faces of their kids, only the kinds of cars they drive and if their dogs are tied.”)

Almost all of the songs pivot on the most Spartan of tunes played on a single 12-string acoustic guitar, and musically a lot of it sounds very much like unvarnished US folk from a pre-internet era. Lyrically, too, and in common with many historic musicians of that genre – like Woody Guthrie, to whom he pays homage on the album’s last song and early Bob Dylan, with whom he shares his birthplace of Duluth, Minnesota – Parr does a fine line in acerbic and impassioned dissections of social injustice.

But for all this is well-trodden ground, even down to the density of his lyrics and the way they come close to completely subsuming the music, Parr offers new outlooks all the same. That’s partly because “These songs feel more like poems to me,” he explains in the copious sleeve notes, “and I’ve kind of let them have their way in that respect. []. Rather than his usual strategy “of trying to stick words to a more or less rigid framework of chords or melody, I’ve let them have their lead.”

On top of that, Parr is now working from what he (or rather, as per those lengthy sleeve notes, his mom) once called the shift in perspective that comes “when we turn from gazing into the future to gazing back at the past, as if we’re adrift in the current, slowly turning around.” In other words, impending old age.

As he points out in one of the 11-song album’s highpoints, the opening title track, such is the way we’re shaped by society, consumerism and our chronic lack of self-knowledge, that we may not understand, let alone like, what we see in our increasingly predominant personal rear-view mirrors:

“Money can’t buy back that ’64 Falcon that you sold in your twenties and then regretted it was gone because you thought it contained some meaning or some answers to your life that you never bothered to question or take a good look at.”

“Now you’re in your 50s why can’t you forget how the chrome bumpers shined in the sun if you could just go back even for a minute you could forget how you don’t even know what it was you lost.”

‘Tell me what it is you think you regret’, he demands in the same song. And, as he looks back more at his past, that urge to get a clear vision on everything from memories of his father (‘Blues for Whitefish Lake’), to gratitude (‘817 Oakland Avenue’), solitude (‘Everyday Opus‘) or a simple walk in the dark (‘On Listening To Robert Johnson’) is a driving force through the whole of LotBDA.

Often based around a journey of some kind, by boat or car or on foot, the need for changes of perspective sometimes truly give age-old social concerns a kind of freshness that emphasises the plight of those caught up in their consequences. Whoever would have imagined a canine-centric vision of loneliness and homelessness in ‘Walking back From Willmar’, for example? Dealing with a security guard who lives in “an abandoned reefer at the end of the parking lot”…

“Sometimes he’d come into town, a stray dog trailing at his heels

All the stray dogs love Tony because he knows exactly how it feels.”

Parr’s singing is snappy and articulate, too. That’s something critical for verses that rely on an acute eye for detail rather than high drama to assist in maintaining the listener’s interest. (There are no murder ballads on LotBDA and this is probably the first country-folk album the reviewer’s ever heard that doesn’t have at least one person getting shot somewhere along the way).

The process of focussing on the words is helped that musically each song all have extremely repetitive formats. They are often just a simple single riff or verse form opened up just enough to ensure the reams of poetry can rest atop of a very stable melodic base. More importantly, the momentum is maintained by the quiet emotion in his voice, his sense of involvement and unpretentious sympathy for the socially marginalised individuals that so often feature in his songs. Prior to turning full-time musician, Parr’s last ‘day-job’ was working with the Salvation Army on outreach, and there’s a strong sense some of those people he came across have gained an extra lease of life here..

After these torrents of words, seeing out the album, though, is a 15 minute instrumental entitled ‘Decoration Day’ – in the sleevenotes, Parr says that’s “the day we tended the graves of our family and thought about the small piece of history that pertains to us specifically.”

Perhaps the most striking element is – and for a song about spending time in burial grounds, that’s an inspired decision – the seemingly interminable, underlying silence of ‘Decoration’ Day, broken by brief snatches of repeated tunes and riffs on a single guitar and occasional mournful notes from a cello.

The sounds are so fragile, the whole song feels very precarious somehow. But the two instruments, guitar and cello, eventually stilt-walk their way over the soundlessness into the slowest of slow-motion finales, briefly backed by (for the first time in the album) the occasional rattle of some drums. Quite a conclusion.

By this stage in the game, it probably hardly needs pointing out that ‘Last of the Better Days Ahead’ is a pretty idiosyncratic kind of album, for all the simple, accessible musical formats and genres keeps its collective feet firmly on the ground. But that’s ultimately its strongest point, too.

Socially and musically, maybe even poetically, Parr is thinking outside the box (and it seems like living outside the box as well, but that’s another story) and he makes the listener do that too, both about subjects that are deeply personal and which reach out well beyond that. If these are what the last of the better days ahead are going to be like, then, bring ‘em on.