OK, so the backstory is well known. Glenn Campbell was, and remains, one of popular music’s greats. A storied session guitarist and vocalist he appeared on some of the 60s most iconic records – ‘River Deep Mountain High’, ‘Pet Sounds’ and ‘Viva Las Vegas’. Playing as part of the wrecking crew he backed Simon and Garfunkel and contributed to Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’ and also played with some of the absolute core americana artists such as Gene Clark, Merle Haggard and Bobbie Gentry. All the while he was releasing a stream of relatively popular but only mildly diverting country-pop LPs. Then he hooked up with Jimmy Webb towards the end of the decade and created moments that will forever remain amongst the 20th century’s greatest art. Anyone who doesn’t believe that ‘Wichita Lineman’ and ‘Galveston’ belong in this category is reading the wrong piece and should leave now.

OK, so the backstory is well known. Glenn Campbell was, and remains, one of popular music’s greats. A storied session guitarist and vocalist he appeared on some of the 60s most iconic records – ‘River Deep Mountain High’, ‘Pet Sounds’ and ‘Viva Las Vegas’. Playing as part of the wrecking crew he backed Simon and Garfunkel and contributed to Spector’s ‘Wall of Sound’ and also played with some of the absolute core americana artists such as Gene Clark, Merle Haggard and Bobbie Gentry. All the while he was releasing a stream of relatively popular but only mildly diverting country-pop LPs. Then he hooked up with Jimmy Webb towards the end of the decade and created moments that will forever remain amongst the 20th century’s greatest art. Anyone who doesn’t believe that ‘Wichita Lineman’ and ‘Galveston’ belong in this category is reading the wrong piece and should leave now.

Into the 70s he had continuing commercial success creating records of arguably diminishing artistic merit until, like a number of his contemporaries, his solo career seemed to run out of energy. His record releases slumped to endless rehashed compilations and ‘live’ albums. He was rarely seen other than in infrequent ‘cabaret’ like shows and the occasional gossip column appearance for his drug and alcohol excesses or his somewhat less than-liberal political hectoring. The latter stages of this very brief bio’ really suggest Campbell is not classic AUK fodder then, especially the right-wing god-bothering and god-awful highly polished country-pop records of the late 70s and 80s. But there is a twist to come.

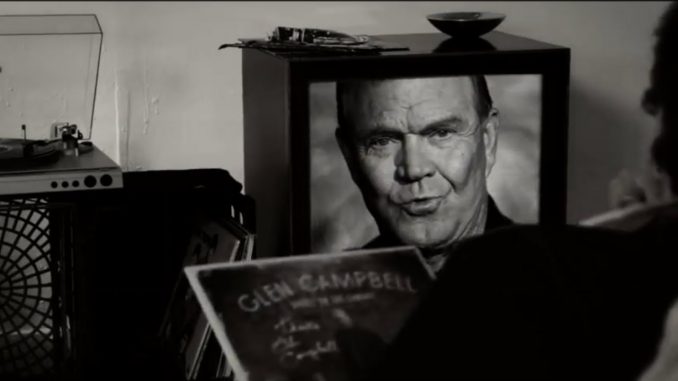

Growing up, as I did a provincial, part-time punk in late 70s Bradford, all this stuff (‘Rhinestone Cowboy’ nonsense as I saw it) made him anathema to me. I don’t recall the exact moment that my head was turned and I realised the glory of the Webb years and that those two singles in particular, were unimpeachable mini-masterpieces that it would remain impossible to surpass for as long people made 3-minute ‘pop’ records. Even then though I owned all the Glen Campbell I needed with a scrappy 80s vinyl compilation ‘At the Country Music Store inc’ (really, that is what it is called!), which I played whenever I wanted to evangelise about the ‘Lineman’. That was pretty much it for me until in 2008 when there was an ill-judged attempt to bring him into the realms of those ‘marquee’ artists who have been rejuvenated by the application of a cool, hipster sheen and a dose of alternative indie cred’. ‘Meet Glen Campbell’ saw him covering songs by artists that were on my radar; Green Day, Lou Reed, Foo Fighters among others and most importantly Paul Westerberg.

However ‘Meet Glen Campbell’ didn’t get the level of attention of other ‘back to their future’ albums by the likes of Tom Jones, Elton John, Neil Diamond, Loretta Lynn or even Johnny Cash. But it did launch his partnership with producer Julian Raymond, who went on to helm our classic Americana LP 2011’s ‘Ghost on the Canvas’, a record of rare and elegiac beauty. later, they made ‘See You There’ and ‘Adios’ together but these are patchy patchworks of re-workings and too obvious covers that don’t deserve to be mentioned in the same breath as ‘Ghost’. Bearing in mind the reinvention or rejuvenation records of these other artists, ‘Ghost’ is, in spirit perhaps, nearest kin to Loretta’s ‘Van Lear Rose’ but, love it as I’m sure we all do, over time that record seems, sonically at least, more and more like a Jack White record with Loretta as the songwriter and guest vocalist. Campbell’s effort on the other hand reverberates with his personality, even though he is responsible for co-writing just 5 of the songs.

The other 5 tracks are bold covers of songs by some of the next generation’s keenest musicians. The choice of compositions by Paul Westerberg, Jakob Dylan, Robert Pollard and Teddy Thompson may seem surprising and at first appears to speak more to Raymond’s connections than Campbell’s tastes. However, to hear Campbell talk about and perform these songs it is clear that whatever the process by which they were chosen, he has developed a close and meaningful relationship with them. He plays them straight, steadfastly avoiding any temptation to try and appeal to their original audience. He inhabits these songs like they were written especially for him, for this particular project even and they perfectly complement the themes and moods of the record. It may have been sentimental tough guy Westerberg’s contributions that drew me in to begin with and the title track, originally from a home-recorded 2009 bits and pieces project, is worth the price of admission alone. The themes of the song can easily be read as reflecting the transitions that Campbell is undergoing, between the different mental states occasioned by his condition and across the great divide as he approaches the end of his journey. The track begins with nothing less than the keyboard ‘bleeps’ echoing the telegraph pulses that open ‘Wichita Lineman’ and the mood of lushly produced, melancholic post-midnight reflection that effortlessly sets the tone for the record to come.

In offering this as a classic Americana album I really just wanted to convey how wonderful this record sounds, the luxuriant almost baroquely arranged drama of it, the life-affirming yet heart-aching melancholy and the aching longing of the beautiful arrangements. It is though, just so difficult to write about it without focussing on the conditions of its creation and that is exactly as it has to be. Between ‘Meet’ and ‘Ghost’ Campbell received the dreadful diagnosis of Alzheimer’s and this was to shape everything about ‘Ghost on the Canvas’ and the rest of his career until his death in 2017. It sees him taking stock of his life and career in a way that is at once out of step with the majority of his cannon but also seem natural and unforced. Providing a perfect coda to 50-plus years of recording.

Without these exigent circumstances the record would likely not have received as much attention when it came out and, probably, we wouldn’t be writing about it here. That’s not to say it is not worthy of our attention simply as a work of art, it unquestionably is. But it is also not possible to separate the art from the artist’s state of affairs. The record is intimately and intricately bound up with Campbell’s diagnosis and his attempts to deal with this, which ultimately means his feelings about his life to this point, about how he can live out the rest of his life and about how it will end.

Artists writing and performing songs about their lives and their experiences of living them is pretty much the bread and butter of popular song and americana in particular. The genre would be pretty thin on the ground without the autobiographical muse. Those writing and performing about their (impending) death and their experiences around it are, thankfully, much less prevalent. Now we all know that someday we’re going to come face to face with the grim reaper. Fortunately most of us are not cursed with the knowledge that this is about to happen sometime soon. Artists who are in this position have a singular opportunity to compose and perform some kind of testimonial that gives character to their end times as well as to their life before. They can shape their own acclamations, create their threnody if you will. Their representation of this account can of course be expressed unflinchingly directly or in ambiguous and metaphoric doggerel. Either way it is rarely difficult to interpret and is often moving to experience.

As the cohort of americana writers and performers ages and their ‘chaotic’ lifestyle choices catch up with them, then such records have become more common. More of them are choosing to connect with us from the end of their road. It’s not perhaps a ‘genre’ as some have claimed but the list of those delivering ‘goodbye’ albums (whether pitched as such or not) is formidable. Final releases by Leonard Cohen, Leon Russell, Warren Zevon, Wilko Johnson, Gregg Allman and Sharon Jones (add Bowie and Freddy Mercury, the list could go on…) have all appeared in the shadow of their final curtain. These records have been relentlessly scoured for clues about the artists’ state of mind in their twilight times and whilst it may be questionable as to whether all of them are explicitly exploring their creators’ great departure there can be no doubt that they come laden with work that we can hear as a reflection of them facing their final act.

When George Harrison tells us that he is “Talking to myself, crying as we part”, or Warren Zevon eventually pleads that “Shadows are falling and I’m running out of breath, Keep me in your heart for a while” and when Leonard Cohen mournfully intones “If you are a dealer I’m out of the game, If you are a healer I’m broken and lame, I’m ready, my Lord”. we know just exactly what is at stake, regardless of whether we share all the feelings at play. Even when artists call up their life’s final act as muse, it remains comforting that such dark matter can often help us all feel more alive. This is how it is with ‘Ghost on the Canvas’, a record that unflinchingly engages with Glen Campbell’s experience of Alzheimer’s and his encroaching decline at the hands of the disease, yet somehow remains uplifting and almost joyous throughout.

It is the most affecting album in my collection and I have given up trying to work out just why. Yes, clearly the fact that he is singing about crossing over speaks to us in emotional tones but there are many 1,000s of records that do this without having the same resonance. In many ways ‘Ghost on the Canvas’ can be (and has been) labelled as sentimental, maudlin and nostalgic, knowingly so even. What saves it from all this and sets it apart for me is the lush, timeless and transcendent sonic beauty of the performances and production together with the personal humility of Campbell as he embraces his humanity in what he believes are his most vulnerable, closing moments.

Perhaps it is the incongruity of the joyful and almost opulent musical setting of ‘Ghost on the Canvas’, which sounds like nothing more nor less than classic 1960s ‘Webb era’ Campbell and the exquisitely mournful melancholy of the record’s lyrical leitmotifs that provides its affecting nature. Whist we are never more than a beat away from being reminded about his state of affairs, he never once stoops to self-pity or recrimination and modestly, yet poignantly, reminds us of the past triumphs of his career in a thoroughly modern setting. Campbell’s gloriously undimmed tenor, which he employs with authority and a masterly edge, takes us right back to those glory days as does the record’s stirring, almost widescreen production. There are also half a dozen brief and evocative instrumental interludes that pepper the album and far from being a distraction, these pay tribute to places and events in his life and career; his hometown of ‘Billstown’ and the sumptuous, wordless vocal harmonies on the final ‘The Rest is Silence’ reference his time as a Beach Boy.

Whilst it is often the covers here that draw attention, Campbell’s originals (composed with Julian) are equally strong and perhaps even more poignant. Through them he is taking stock in a direct and unambiguous way. So ‘Thousand Lifetimes’, is a canny challenge to his mortality, “Strong” sees him address his vulnerability and insecurity and ‘A Better Place’ reflects his ongoing gratitude and optimism in the face of the tremendous challenges he is experiencing. The final song ‘There’s no me… Without You’ talks directly to Kim his wife who helped him through his troubled 80s (even the excessive Milk of Magnesia & vodka cocktail consumption!) and its message is crystal clear from the title alone. This directness is something we are not used to from Campbell but offers a moving dénouement for his career. The final moments of the song and the record are devoted to an extended, elegant guitar coda with guests Billy Corgan (The Smashing Pumpkins), Brian Seltzer (Stray Cats) and Rick Nielsen (Cheap Trick), exchanging tuneful, reverb-soaked solos, taking us back to Campbell’s own heyday as a crack guitar slinging session player. This array of guests from the indie/rock firmament (also including some Dandy Warhols, Jellyfish, Guided by Voices and a hardcore Danzig) being the final testament to the esteem in which he was held.

‘Ghost on the Canvas’ enabled Campbell to move toward the end of his career both on his own terms and with a real statement about his status as an artist and in his life. It was at once the renaissance of Campbell’s standing as a true giant of the music, the pinnacle of his art in its long form and a fitting summation of all he was about as an artist and a person. It is undoubtedly a classic americana LP in any way you count ‘em.

PS – extra points if you can spot all the Replacements references in the video!

A great read for a great final album from Glen.

Top writing about a great album

Outstanding writing. I can’t recall how many times l go back to ghost on a canvas it’s a beautiful reset for me