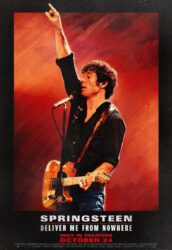

A dark period of Bruce Springsteen’s life finds its way to the silver screen.

After a long and illustrious career, Bruce Springsteen’s life has finally received the Hollywood treatment. Given his status as a music legend and the proliferation of films dedicated to music stars in recent times, it was only a matter of time before the Boss had his own biopic. This time, the project is helmed by writer/director Scott Cooper, who is no stranger to music films. In 2009, he released his directorial debut, “Crazy Heart”, in which Jeff Bridges portrays an ageing country-folk star whose now-solitary life is in turmoil due to his drinking problems. Therefore, despite some ups and downs in his career, Cooper seemed from the get-go like an appropriate director for “Deliver Me From Nowhere”, which he also wrote, adapting the homonymous book by Warren Zanes (while also taking some elements from Springsteen’s autobiography “Born to Run”).

After a long and illustrious career, Bruce Springsteen’s life has finally received the Hollywood treatment. Given his status as a music legend and the proliferation of films dedicated to music stars in recent times, it was only a matter of time before the Boss had his own biopic. This time, the project is helmed by writer/director Scott Cooper, who is no stranger to music films. In 2009, he released his directorial debut, “Crazy Heart”, in which Jeff Bridges portrays an ageing country-folk star whose now-solitary life is in turmoil due to his drinking problems. Therefore, despite some ups and downs in his career, Cooper seemed from the get-go like an appropriate director for “Deliver Me From Nowhere”, which he also wrote, adapting the homonymous book by Warren Zanes (while also taking some elements from Springsteen’s autobiography “Born to Run”).

“Deliver Me From Nowhere” is not the Springsteen film many people might expect, in the sense that it’s not the definitive retelling of his life. However, this is far from a bad thing, since it prevents the film from becoming a generic success story, hard to avoid when covering the entirety of an artist’s rise to fame. Following the footsteps of another recent biopic, Bob Dylan’s “A Complete Unknown” (reviewed here), “Deliver Me From Nowhere” centres on a specific period of its protagonist’s life, not necessarily representative of his music and life, but one of great importance: the conception of “Nebraska” an album that meant a turning point in his career.

Jeremy Allen White is the actor chosen to fill Springsteen’s boots, both figuratively and perhaps literally, since some of the Boss’s real clothes were used in the making of the film. White sports some of the singer’s iconic garments, Levi jeans, leather jackets, plaid flannel shirts, white tank tops—all those items that made him a working-class icon, more immediately accessible than some of his peers. Though he had no previous experience in music, White showed great dedication to the role through intensive singing, harmonica, and guitar lessons (although previous to the role he had never picked up a guitar, you can see him playing and hear his real voice almost exclusively while on screen), as well as physical coaching to take on the singer’s charismatic persona. Allen does some great voice work in the film, and despite his physical dissimilarities with Springsteen, he manages to pull you into his version of the singer, making “the character” his own. Only during the rock performances does Allen seem to have some difficulty capturing the artist’s likeness. But these moments are fleeting, for Springsteen is entering a new musical period with his dark, acoustic “Nebraska”.

Allen is joined by a remarkably strong cast, which includes Jeremy Strong, Stephen Graham (a standout performance), Odessa Young, and Paul Walter Hauser, all of whom bring their characters to life with nuanced performances that enhance the film’s authenticity. “Deliver Me From Nowhere” finds its tone halfway between commercial and arthouse tendencies, making for an entertaining yet insightful experience.

Again, the choice of focus is interesting because “Nebraska” is likely not the first album that comes to mind when thinking of Bruce Springsteen. Prior to its recording, Springsteen had released five albums, including “Born to Run” and “The River”, which was his biggest commercial success to date, reaching number one on the American album charts. It meant an unprecedented level of success, which materialised into an intensive tour and newfound attention for Springsteen. Overwhelmed, he decided a break was necessary to slow things down and reconnect with both himself and his roots. Thus, he rented a secluded house in Colts Neck, New Jersey, and soon embarked on a new project that would be a process of self-discovery, though a dark one indeed.

“Nebraska” was recorded in Springsteen’s bedroom, without the E-Street Band, as a way to avoid the expenses of writing in the studio. Making demos before taking the material to the band seemed like a sensible option, which allowed Springsteen to focus on himself as an artist removed from any external influence, other than that which he chose to pursue. The album was recorded using a TEAC 144 Portastudio recorder and two Shure SM57 microphones, aimed at a chair set at the foot of his bed. There, Springsteen would play around with different ideas and eventually layer them on the four-track recorder, creating basic arrangements with his Gibson J-200 acoustic guitar, harmonica, mandolin, glockenspiel, and even some percussion. There are conflicting accounts of the recording process, but it likely took place between December 17, 1981, and January 3 of the following year. Mike Batlan (played by Paul Walter Hauser), who assisted Springsteen in setting up the home studio, also passed the recording through a Gibson Ecoplex to get a 1950s-style delay effect. A Panasonic Boombox was then used as a mixdown deck to get the recording onto a cassette, which Springsteen sent off to his manager Jon Landau (Jeremy Strong), with a lengthy letter detailing his view on the album and each recording.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve probably realised I will be digging deep into the film and the real-life events that it narrates. In any case, fair warning, there will be major film spoilers from here on.

“Deliver Me From Nowhere” begins with a black-and-white sequence in which a young boy is taken by his mother to fetch his father from a local bar. Timidly, he approaches the bulking, morose man sitting at the countertop and says it’s time to go home. The family’s troubled dynamics are perfectly captured in this short sequence, which abruptly cuts to Springsteen, now in his thirties, performing one of the last shows of The River Tour. Although he’s not yet the global icon that he will become only a few years later, he’s exhausted by the new levels of fame. His decision to lay low for a while is fully supported by Landau, who will be a pillar of support amidst Springsteen’s period of emotional turmoil.

And so, Springsteen heads off to his new rental in Colts Neck, where he leads a life close to that of a recluse. He mostly spends time alone, breaking the monotony with nights at the Stone Pony, a live-music venue where he plays with local artists, including Cats on a Smooth Surface, the house band. After one of such concerts, much more discreet than his recent performances around the country, he runs into an old schoolmate he barely remembers. After a quick catch-up, Springsteen is introduced to his sister, Faye Romano, who he soon starts dating. Slowly, an honest affection develops between them as Springsteen takes Faye out, together with her young daughter. It’s a family structure he was clearly missing, quite different from what he experienced growing up with his violent father. Whether he’s fully aware of it or not, there’s a pain he carries with him wherever he goes, and which determines his own relationships. But more on that later.

Springsteen has begun working on new material, a significant departure from his latest releases, even if certain lyrics from “The River” anticipated what was to come. The new songs are raw, bleak, and closer in tradition to classic Americana genres. There are many influences at play, but in the film, as is understandable, these have to be streamlined. For instance, films that inspired Springsteen during this time are reduced to “Night of the Hunter” and especially “Badlands”, though others like “The Grapes of Wrath” and “Wise Blood” played a part in his creative process. After casually catching “Badlands” on TV one night, Springsteen is inspired to investigate the murders perpetrated by Charles Starkweather, poring over newspaper clippings at the local library. The works of Flannery O’Connor are also shown to be a great inspiration. What is surprising, perhaps, is the way the musical influences are dealt with. In one scene, Springsteen listens to Suicide’s hellish and fascinating ten-minute song ‘Frankie Teardrop’, but there are no mentions of his interest in Bob Dylan and Woody Guthrie, whose biography was also a big inspiration at the time. Perhaps it’s the eclectic nature of cinema, in constant discourse with every other art form, but given the protagonist’s status as a music icon, it seems like an odd choice on director Scott Cooper’s part.

The songs themselves turn out to be somewhat varied. The original cassette recorded by Springsteen included fifteen songs (with two additional tracks recorded at a later date), but only ten ended up on the final album. One of the film’s highlights is its attention to the creative and technical processes, even if details are simplified for the sake of the film’s flow. When writing about the Starkweather crimes in the song ‘Nebraska’, Springsteen decides to change the lyrics from the third to the first person, showing a deeper connection with the events described. The songs of this period tell stories like that of a struggling man caught up in a mob war (‘Atlantic City’), another senseless murder by a worker who is laid off and takes his frustration out on a clerk (‘Johnny 99’) or an honest policeman who decides against turning in his own criminal brother (‘Highway Patrolman’). Grey moral conundrums and the bleakness of life run through “Nebraska”, accommodating more personal stories about Springsteen’s origins and his father, in tracks like ‘Mansion on the Hill’, ‘Used Cars’, and ‘My Father’s House’. Springsteen finds a way to make peace with the underlying violence of his own life by immersing himself in the world’s darkness. It’s a way to process his own pain, and perhaps the only way he can eventually find peace. However, that is still far off, and things will get worse before they get better.

Once the demos are ready, it’s time to record with the band. At least that’s the idea. After hearing the cassette, Landau is supportive of Springsteen’s new songs, even if somewhat surprised at the distancing from the sound that has earned him a number one album. Nonetheless, they head over to the Power Station studio in New York, in an attempt to capture on tape new renditions of the demos, fleshed out with the aid of Springsteen’s usual musicians. Once there, hardly anything seems right. The songs aren’t reinterpretations of the original ideas, but versions that simply add noise to compositions that don’t need it. Springsteen doesn’t want to lose their essence, what he liked about them in the first place. The band and technicians all seem more enthusiastic about the recordings, but they seem to have reached an impasse. Springsteen won’t give in. After all, the songs represent his history, memories, and way of dealing with the world. A decision is reached to shelf the few songs that work with the band (and will later become part of “Born in the USA”).

But what’s there to do with the remaining songs? Because it’s more than a few that haven’t worked out. Springsteen has an idea, the only one that will fulfil his vision, and as he explains it, you can almost hear the technician’s souls leave their bodies. The album is ready—it’s on the cassette. The problem is that the songs were recorded with low-fidelity equipment, much below the standards for an artist of his calibre. The engineers are far from happy, but their job is to realise the artist’s vision. Still, they encounter significant challenges with noise reduction and the transfer to vinyl. Due to excessive phasing and the odd sound of the recording, the needle keeps jumping out of the vinyl’s groove. As Toby Scott, tasked with mastering the recordings, explained in a 2007 interview: “We went to Bob Ludwig, Steve Marcussen at Precision, Sterling Sound, CBS. Finally, we ended up at Atlantic in New York, and Dennis King tried one time and also couldn’t get it onto disk. So we had him try a different technique, putting it onto disk at a much lower level, and that seemed to work. In the end, we ended up having Bob Ludwig use his EQ and his mastering facility, but with Dennis’ mastering parameter.” The film details the challenging process of turning the cassette into the final records, highlighting its unorthodoxy with a recurring joke on how the cassette doesn’t even have a case.

However, not all the writing in the film is as neat as this. The attention to detail is undeniable, but certain scenes and bits of dialogue seem too procedural. It’s clear there was a lot of information to get across, which sometimes results in uninspired solutions. For instance, the scenes between Landau and his wife are ostensibly only there to give an idea of Springsteen’s thought process without a monologue from the protagonist, which would have been even more hackneyed. Since her character only appears in these brief scenes, it begs the question of whether it wouldn’t have been more natural to attempt this through an already-established character. Cooper makes up for some of these decisions with subtle directing choices. You might notice the widening space between Springsteen and Faye in the shots used when their emotional distancing begins to grow, or the flickers of light on Landau’s face in one of the final scenes, reminiscent of the raging fire seen in the footage of “Badlands”, but whose actual source turns out to be stage spotlights.

You enter the final stretch of the film feeling Springsteen is sabotaging himself. Just like his father, who dealt with psychological issues and ended up hurting himself and his family, Springsteen can’t deal with his relationship with Faye, who reproaches him for his lack of courage. He’s running away because he has become emotionally crippled, and it’s the only solution he’s capable of to avoid greater pain. At the same time, the suits at Columbia are left in a state of shock upon learning about the album’s promotional strategy, or the lack thereof. There will be no touring, singles or interviews, and the cover artwork won’t feature Springsteen’s face—instead, a stark black and white photograph of a derelict country road under an oppressive overcast sky. In addition to this, after considering various options, the album will be called “Nebraska” in reference to where the Starkweather murders took place. The scene where Landau explains this strategy is hilarious, but one wonders whether any coronaries were suffered as a consequence. Springsteen seemed set on career suicide. Had he not had “Born in the USA” on the back burner, things might have turned out quite differently in the long run. “Nebraska” would eventually be a greater commercial success than expected (reaching the third position in the American charts), but even so, Springsteen would have faced serious challenges if the industry had stopped considering him a potential hit maker.

At the end of the film, Springsteen leaves New Jersey for Los Angeles, where he has bought his first house. It’s a way of distancing himself from his problems, but he’s unable to outrun his demons and, for the first time, realises he’s in serious trouble. After a heartfelt phone conversation with Landau, he realises he needs professional help, a decision that would have taken much more courage at a time when mental health issues weren’t as discussed as today. The choice not to explicitly voice Springsteen’s depression throughout the film results in a more powerful ending. In the film’s epilogue, he is shown thriving both professionally and emotionally. After a successful concert, he has an odd yet emotional backstage encounter with his father. In physical and mental decline after years of alcoholism, medication, and physical work, his father asks him to sit on his knee for the first time in his life. They share what are probably some of the most honest words to pass between them, and after his own battle with depression, Springsteen comes to terms with his father’s mistakes, finding it in his heart to forgive his abuse from a place of understanding not easily accessible to many people.

“Deliver Me From Nowhere” is a peculiar case among biographical films. The unusual, bold decisions made by Springsteen with “Nebraska” are echoed by the film’s own choices, the most blatant of which is to set the film in this particular period of his life. The appeal to wider audiences might not be as great as if a different approach had been taken, but the result is more memorable. According to recent interviews, Springsteen seems keen on exploring other chapters of his life on film, so perhaps “Deliver Me From Nowhere” could contribute to a fresh perspective on what a biographical picture can and probably should be. Individuality is found in smaller moments that can’t be covered when taking on a person’s entire life, and for this reason, “Deliver Me From Nowhere” leaves you feeling closer to the man behind the legend.

Great review, thanks. I really enjoyed the film and it helped being a Springsteen fan.