Renaissance music in the morning, Oliver Messiaen for lunch, and Merle Haggard at night.

Clive Carroll is a leading British guitarist who was educated at London’s Trinity College of Music. However, he hasn’t let a formal musical education dull his natural musical curiosity and eclecticism, and that musical eclecticism is displayed in the full-on Clive Carroll’s double album tribute to that other British guitar legend and composer John Renbourn, ‘The Abbot’. The tribute is particularly heartfelt because Powell and Renbourn were friends who worked together. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Clive Carroll over Zoom to discuss ‘The Abbot’ and John Renbourn’s contribution to music. Clive Carroll explains how he has focused on his own take on John Renbourn’s compositions rather than simply trying to recreate the Renbourn originals. While John Renbourn came to prominence as a member of Pentangle, which he formed with fellow musicians including the iconic guitarist Bert Jansch in 1968, and will probably be best remembered for this, Clive Carroll explains that he thinks that Renbourn’s music is comparable to what the Pre-Raphaelites achieved in the art world at the end of the 19th Century. He also shares the depth of his own musical eclecticism which is possibly the equal of Renbourn’s own, and he fanaticises about the possibility that Robert Johnson and Ivor Stravinsky could have collaborated together.

How are you, and where are you?

I’m in my car just outside of York somewhere because the hotel wi-fi isn’t up to it. So here I am in the driver’s seat which isn’t very rock & roll.

Your own guitar style mixes formal classical with various folk and roots styles. Why do you think you are so eclectic?

I think I’ve just got a wide curiosity, but you have to remember the old saying “Jack of all trades, master of none”, but I can’t help finding out about Elizabethan music while improvising modern jazz. It is a curiosity that I shared with John Renbourn who had similar thought processes.

Your music has received many plaudits, but how easy is it for a guitarist to build a career in the 21st Century?

That’s an interesting question. I think it is a career you have to build slowly, and there are people out there who have a similar appreciation for what can be considered eclectic taste, lots of people out there like lots of different things. I suppose the limitation already for a concert is that it is just guitar, and I think in this day and age it is quite difficult to make a living as an instrumentalist. The guitar is one of the most popular instruments in the world and there are lots of people who play it, and I suppose if it has got a folk blues or possibly a jazz tinge there is an audience out there for it. Those are the three foundations of what I do, I went to a music conservatoire in London. Unfortunately, if it has classical in the description you are probably drastically limiting your audience judging by album sales and concert tickets. That’s a real shame because the music is substantial, but it is hard for people in this day and age to listen, there doesn’t seem to be a lot of time for people to be able to listen.

John Renbourn was very eclectic mixing folk, jazz, blues with the baroque folk that maybe he is best known for. Why have you chosen to celebrate the baroque side of his work?

It is just a coincidence that it was that. The album is still fresh in my mind and I don’t hear that but you are not the first to say that so I’m taking it onboard. The way I approached the album was in three strands. The first was I decided to put it together and include pieces because of my connection, in terms of friendship, with John and what we played whilst I was on tour with him. Certain pieces like ‘So Clear’, ‘Ladye Nothynge’s New Toye Puffe’ and ‘Little Niles’, all draw me back to times I spent with John on the road. The second aspect is that I put some feelers out to some people I know who are absolute John Renbourn fanatics to name ten pieces they would like to see on a John Renbourn album, and you won’t be too surprised to hear that most requests were not too dissimilar. So I had a body of work there that needed to be interpreted in my own way, and then I then listened to most of John’s back catalogue, his recorded output, and I found pieces that I felt really needed to be re-released in some guise. As with all the pieces on what was going to be a single album but is now a two-hour double album, I didn’t want to recreate exact interpretations of the originals because you may as well just listen to the originals. So, I tried to do something different with every track, whether it be a reinterpretation of a medieval-influenced piece, or completely reorchestrating the piece as in the case of ‘The Pelican’ which originally was just guitar but is now arranged for flute, accordion, bass clarinet, glockenspiel naturally, and a few other things, cor anglais is on that one as well.

It is just a coincidence that it was that. The album is still fresh in my mind and I don’t hear that but you are not the first to say that so I’m taking it onboard. The way I approached the album was in three strands. The first was I decided to put it together and include pieces because of my connection, in terms of friendship, with John and what we played whilst I was on tour with him. Certain pieces like ‘So Clear’, ‘Ladye Nothynge’s New Toye Puffe’ and ‘Little Niles’, all draw me back to times I spent with John on the road. The second aspect is that I put some feelers out to some people I know who are absolute John Renbourn fanatics to name ten pieces they would like to see on a John Renbourn album, and you won’t be too surprised to hear that most requests were not too dissimilar. So I had a body of work there that needed to be interpreted in my own way, and then I then listened to most of John’s back catalogue, his recorded output, and I found pieces that I felt really needed to be re-released in some guise. As with all the pieces on what was going to be a single album but is now a two-hour double album, I didn’t want to recreate exact interpretations of the originals because you may as well just listen to the originals. So, I tried to do something different with every track, whether it be a reinterpretation of a medieval-influenced piece, or completely reorchestrating the piece as in the case of ‘The Pelican’ which originally was just guitar but is now arranged for flute, accordion, bass clarinet, glockenspiel naturally, and a few other things, cor anglais is on that one as well.

That’s how the album came about, and I discovered in one folder in his collection, which is now housed in The University of Newcastle, two pieces he had started to write parts for. You might like to know that 10,000 compositional pages have been digitalised right now he was so prolific. So, most of his work hasn’t been discovered yet, but those two pieces with their parts tell me he intended for them to be recorded and I’m pleased to bring two unrecorded pieces to this album as well.

You have added to John Renbourn’s arrangements and songs rather than taking a simple tribute band approach, what did that feel like, particularly as you knew John?

It didn’t feel like sacrilege. John was always interpreting his pieces, writing extra sections, cutting sections, re-voicing them, and a lot of the time rearranging them for a guitar duo instead of the solo format. It is in that spirit that I approached the whole project, actually. That was John, constantly tinkering with his pieces, mind you, Johann Sebastian Bach did the same thing.

I suspect that today we generally have a very restricted view of what classical music is all about.

Yeah, Bach was a great improviser he would knock something up and then revamp it, and you can hear the same voice channelled through different suites.

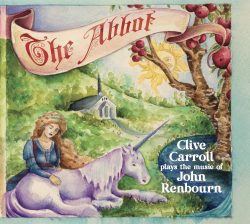

The cover of ‘The Abbot’ is very evocative of John Renbourn, who designed it?

I wanted to stick to a late ‘60s early ‘70s art vibe. Originally I thought about Peter Bruegel the Elder’s village scene and I wanted everything that was going on in the village to be a reference to one of Renbourn’s song titles, and then I thought about the very fine artist Georgina Smigen-Rothkopf, and I’d seen her artwork before and I thought she would be great for this. On the front cover, you will see a church, and John Renbourn lived in a church and it’s called The Snoot and it’s in the Scottish Borders, and I stayed there many a time and it was freezing cold. John was very proud of the fact he was on the bottom rung of the Council Tax bracket, which is officially for a dwelling fit for inhabitation by livestock. I tried to incorporate as many song titles into the artwork as possible, so you will see ‘The Lady And The Unicorn’, ‘O’ Death’ is represented by the apple tree, ‘Circle Round The Sun’, ‘The Pelican’, ‘The Hermit’ artwork is there, ‘Watch the Stars’ is also in there. So yeah, there’s a whole bunch of titles in that artwork, and I commissioned it.

How did you choose which songs to cover and which would be solo or band tracks?

The whole thing started in March 2020 when we were all stuck at home, and I just pulled out a book of John’s tunes because there were a few pieces I wanted to learn, ‘The Lady And The Unicorn’, ‘Another Monday’, ‘My Dear Boy’, and I was reflecting on a piece. John and I collaborated on a film soundtrack in 2006 called ‘Driving Lessons’ with Julie Waters and Rupert Grint, and they took one track from John’s album ‘Travelling Prayer’ called ‘Estampie’, and I managed to get hold of the original score and instead of a guitar clarinet percussion sound he actually wanted a Moorish flavour so I began to include some Bansuri flutes and Middle Eastern percussion and I realised I could do something different with that. Then I discovered that piece hadn’t been recorded before, and I wanted it rearranged for Medieval ensemble. All of a sudden I had twenty people in mind, and I just never thought about the cost at all. I thought it would be great to have a bass clarinet here and a harp there, a sackbut in this piece. So, I managed to do it and it is a self-release so I watched my bank account drain, but I thought let’s just do it because I really want to get it out there, and it will be a great thing to achieve. On reflection, I didn’t think about the cost but I hope to break even at some point in my lifetime.

Are you touring ‘The Abbot’?

Yes, it is very much a tour to promote ‘The Abbot’ . The tour title is quite long, Clive Caroll Plays The Music Of John Renbourn With Special Guest Dariush Kanani. So I’ve got a younger guy on the road with me, and he is probably more into the Bert Jansch way of playing with that strong rhythmic drive, and it is a great complement to the Renbourn style. We are performing pieces that haven’t been performed live, ever. So, hopefully that is an attraction for people, we’ve taken most of the pieces on the ’Bert and John’ album from the ‘60s, pieces like ‘Red’s Favourite’, ‘Orlando’, ‘No Exit’, ‘The Time Has Come’ has been performed many times obviously, and on the solo front I’m playing ‘Pavan D’Aragon’, ‘Another Monday’, ‘Lady Goes To Church’, these are pieces that have never been performed live. It’s been a fun challenge, and it’s going down alright and we are enjoying it.

You’ve mentioned the number of unrecorded John Renbourn pieces, are you thinking of ‘Abbot 2’?

I’ve got so many other things to do, and I think that was a fair decent innings, I think, two hours of Renbourn. As I mentioned there are hundreds of hours of music to be explored there, but I’ve already moved on to the next project. It was great fun to do, but utterly exhausting and I’m pleased I did it. I also should add I initially wanted to have appearances by people who had worked with John, but then I thought there is no point trying to release that because if for example, people want to hear Stefan Grossman, they will just go to the original to hear the real thing. There is one track at the end of the album that is about fifteen minutes long where I imagine someone walking through a North African souk. So, you get street ambient noise, and I imagine someone walking through and suddenly hearing ‘Sidi Brahim’ which is a piece by John based on a red wine that is neither red nor wine, it is like a purple Algerian or Tunisian gloop. It is a Shakti Indian classical music-inspired piece, but then I imagined someone walking down another alleyway in the souk and hearing this singing and guitar playing in the distance, and that was my chance to bring Wiz Jones onto the project and he sings a bit. The person in the souk turns down another alley and you hear Jacqui McShee’s little group, and then I got Stefan Grossman in a café. So I managed to draw all the original collaborators together in one piece that’s about a quarter of an hour long. It was good fun.

Who are your own personal biggest influences, other than John Renbourn of course?

As you’ve said, I’m pretty eclectic. It can be anything from Guillaume de Machaut and the Notre Dame school, organum music, which was exposed to me for example by someone like Oliver Knussen in the contemporary classical music world, and then I would probably work through to someone like John Dowland and Elizabethan lute music. I would probably bypass a lot of the classical period and just jump into the late romantic, people like Mahler and Eric Satie, and then, of course, early Benjamin Britten. It is amazing to think that while Stravinsky was releasing ‘The Rite Of Spring’ we get the early blues players coming through, and fifteen years later we get Robert Johnson. Robert Johnson and Stravinsky working in parallel, and that would have been really interesting and I like both of them. From the classical world, Oliver Messiaen is a strong influence, and from the jazz world, I’m a huge Joe Pass fan. At the end of the day when I’m sitting at home at night, I don’t want to listen to any fancy guitar playing, I just want to feel the vibe of Lightnin’ Hopkins, or a bit of Merle Haggard or something. A little bit of Renaissance music in the morning, Oliver Messiaen for lunch, and Merle Haggard at night, I love and draw influence from them all.

How’s the coastal walk going?

The coastal walk is something I’ve wanted to do for many years, and I started it just before lockdown with a view I would do it in one go, and I had it arranged with accommodation, some of it would be wild camping, and it is a four and a half thousand-mile round trip. I started from Southwold on the Suffolk coast and if you were going to start it would you go clockwise or anti-clockwise?

I don’t think it would make much difference so I would probably toss a coin.

A lot of people say clockwise but I chose the other way. I went anti-clockwise and after 1023 miles I reached Inverness, and it is utterly exhilarating and you don’t want to stop, it is quite addictive, but I walked for four months from November to March in 2023, and then work took over with a bunch of concerts and some workshops, and 2014 is fully booked on the playing front. I’m restarting it from Inverness in March 2025, I think, which is a bit depressing because it seems so far away but I’m hoping to do four months straight all around Scotland. I can’t wait to jump back on it, I brought the family with me for the last stretch and everyone loved it and nobody wanted to come home. I will recommend it to anybody, and if you want to get a bit of exercise it is free.

We like to share new music with our readers, so currently, what are your top three tracks, artists or albums on your playlist?

I still use a CD player in my car and slots one and two have Adam Hurt who is a gourd banjo player from the northern part of North Carolina, and his gut-string fretless banjo stuff is really something, it moves ya. It is really groovy, that gut-string Appalachian vibe with no frets is a sound I really like. We have a two-year-old so we are listening to ‘Baby Beluga’ by a guy called Raffi. After that, I’ve got some Bill Evans Trio in there, the album ‘Moon Beams’. I’ve also got some Goran Bregović, which is music from Serbia and Montenegro, sort of gipsy big band music which is pretty cool. Then I’ve got Mahler’s ‘Symphony No. 5’, and I love listening to the ‘Adagietto’. So, quite an eclectic mix.

Is there anything you want to say to Americana UK readers?

If anyone is interested in the music of John Renbourn, I’ve tried to create new takes. It is a personal project, this ‘Abbot’ double album, and the aim is to share John Renbourn’s music with as many people as possible from the eyes of someone in their 40s. I’m trying to bring it to a new audience, and I think this music is really strong so whether people want to share my album or Renbourn’s original recordings, I feel it is really important stuff in the history of music because John Renbourn was a creator and not just an interpreter. If you think of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a collection of artists in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there wasn’t really a musical equivalent that was anti-industrial and drawing inspiration from music that was Pre-Raphael. I find it hard to find a strong musical voice in the classical channels, so the closest connection I can come up with really is the music of John Renbourn, from the mid to late 1960s especially, that works in parallel with the Pre-Raphael art movement. I think for generations to come it will be an important chapter of music, baby.