Even coming from Scunthorpe, listening to Hank Williams and Curtis Mayfield you were going to follow the US path.

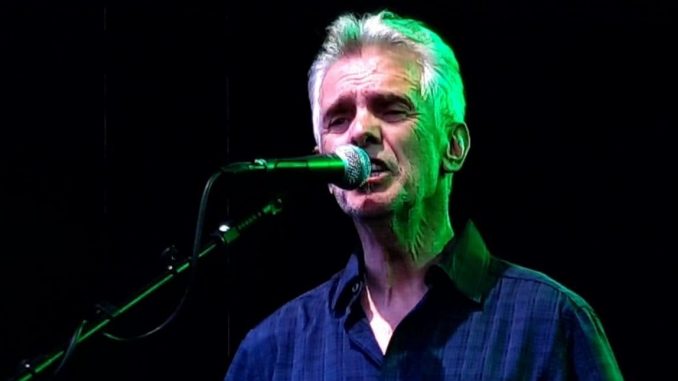

I’ve long been a fan of Iain Matthews and his interpretation of American Folk and Country music. From his early days in Fairport Convention, through his time with Matthews Southern Comfort and Plainsong, and then with his own solo career and the many different musical roads he has travelled down, he has become a particularly fine singer, musician, and songwriter, with a sharp focus on developing his craft. He is a hard-working musician who wants nothing more than to be able to make a living at his chosen trade. I also consider him to be one of the earliest examples of a British musician working in the genre we know as Americana. I mentioned this to publicist Ian Daley, when reviewing the recent Plainsong book by Ian Clayton (there are a lot of ‘Ians’ in this story). I said that I planned to write an article along those lines for our new Americana Bedrock series and he, in turn, mentioned this to Iain Matthews, who said, “Well, if he wants to talk to me about it….”. Iain’s subsequent interview was too good to hold over until I write that article, which isn’t scheduled until the new year. He was open and honest about many aspects of his career and the interview deserves to be shared in its entirety. So here is a rare and exclusive word with one of the greats of British Americana music, whether he thinks he is or not!

You were an early advocate of American folk and country music in the UK. What was it that drew you to that music?

Hard to say. It was early days and like everyone else I knew, I was fudging about, finding my way, listening to anything and everything. Following every finger. Eventually something spoke to me on a deeper level and that was American roots music. Not really the blues, but a more folky thing. That and contemporary acoustic songwriters.

From what I’ve read, you enjoyed your time in Fairport Convention and were surprised when they dropped you yet, in many ways, it was probably the best thing for your career. How do you look back on that time now? Is there anything about that part of your career that you miss?

It was a learning curve. Probably my first big one. Getting the heave-ho from Fairport made me focus and think about what direction I really wanted to move in. I see it as the catalyst that sparked my career. Before that I was basically a singer in a band. Until Sandy came into the band, all the material in Fairport was chosen for adaption, rather than for how it would enhance who we were trying to be. Whatever that was. I’m not one to look back at what could have been. I don’t buy into that stuff. I’m more into destiny. In retrospect it was all good.

Given the current success and high profile of what we now call Americana, do you consider yourself an innovator in bringing this music to a British audience. Would it be fair to say you were ahead of your time in that respect? Why do you think this music is so popular now?

It’s never really crossed my mind. There were others doing the same thing. Brinsley Schwartz for one. Peter Green was doing it with the blues. Bringing it all back home. I was simply taking what I heard and making listeners aware of its existence. I’m talking about the emergence of the 60s American troubadours. Some of us embraced it and made it our own by writing in that style. That’s the key really. Hearing something that turns you on and developing something of your own from it.

Do you pay much attention to what is happening musically in the UK now, especially in terms of Americana music?

Not really. There’s too much to absorb and a lot of it quite honestly is just tilling the same ground and not presenting it in fresh way. Sometimes I wonder if everything’s been said, but then I hear Hiss Golden Messenger, or The Teskey Brothers and realize there are still some out there searching.

It does seem, looking back over your career, that every time you were poised to make a big break you seemed to do something to derail the situation. When the original Matthews Southern Comfort seemed destined for bigger things you quit the band and went into hiding. With Plainsong on the verge of releasing a second album you disappeared to America to embark on a solo career. Was there a self-destructive side to you at that time or was it a case of the grass looking greener somewhere else?

I don’t see it as self-destructive. I look at it as development. For my money, experience and progress are the main reasons for doing what I do. If you don’t move on and try something new, you get stuck in that same old mousetrap of regurgitating your successes night after night and that’s not why I do this. Don’t get me wrong, it’s nice to have success, to be recognized by one’s peers, but it’s not the end all. It’s a perk. If something is not working, I don’t sit around wondering how to fix it. I try something else. I never set out to have hits. I had one and moved on to try something new.

You did seem to lack confidence in your own ability early in your career, despite being recognised as being one of the best singers around at the time. Do you think that was the case and, if so, how did you get past that?

Huh! Honestly, I was a shit singer until I moved to Texas. I could hold a tune, but as an emotive, developing vocalist, it all started in Texas. So did my songwriting.

You’ve become a very successful songwriter yourself, but you’ve continued to search for songs from other writers and have always seemed to champion American songwriters in particular. What has drawn you to the songs you’ve covered over the years – is there a common thread you’ve identified?

The thread has always been finding songs I can identify with, both as a writer and as an interpreter. Once I have the song, I need to know that I can take it someplace else. Present it in a different way. Sometimes after the fact, like ‘Brown Eyed Girl’ which years after recording it I realized that it’s a love song and its essence and appeal lay in presenting it as a waltz.

On the subject of your own writing, it seems to me that you were writing ‘Americana’ songs long before most other British songwriters. The album ‘If You Saw Thro’ My Eyes’, for example, is packed with songs that would more than stand up on today’s Americana scene. What influences were you drawing on at that time. How were you able to tap into that American feel in your songs?

I didn’t know I was. Americana to me is just a convenient label the business has stuck on a certain type of sound to make it easier for them to lasso and identify. I spent 37 years of my creative life living in the USA so, of course, I have a lot of American references and style in what I do. If you begin by listening to Hank Williams and Curtis Mayfield, rather than Ian Campbell and Val Doonican, then of course your path instantly becomes more US than UK.

You moved to Holland at the start of this 21st century and there’s now a thriving Americana scene there. Coincidence? Or have you been instrumental in promoting this style of music in the country.

I moved here for my sanity and to be back in a country that has culture I can relate to. I left just in time if you ask me. Bush junior had just been made governor of Texas and the writing was on the proverbial wall. Back in the 1970s I used to tour here in The Netherlands. There was always a huge acceptance for what I do, here and in Germany. I had nothing to do with getting it started, I just tapped into it and contributed.

We recently interviewed Eric Devries here at AUK and he’s a member of your latest incarnation of Matthews Southern Comfort. What made you decide to start working under that name again and can we expect to hear any new recordings from the band? (Note: There’s an audio clip of the new single from the forthcoming album at the end of the interview.)

Eric is part of the fourth incarnation of MSC. I decided 15 years ago that given the opportunity I wanted to create an alternative musical approach to the one I had back in 1970, using a similar type of song. With the help of a few musical friends, I put a loose band together to try out the concept I had in my head, using more recent influences as touch stones. For example, Tinariwen. It began as ‘a few’ demos and quickly escalated into fifteen (at the time) disappointing tracks. Almost three years later I went back to them and fell in love with the attitude. At that point I finished the recording and called it Kind of New. That was the beginning. Now here we are fifteen years later, with yet another (my fourth) album in the bag. Eric is still on board, along with multi-instrumentalist BJ Baartmans and keyboardist Bart DeWin. We plan to release the album next spring and hit the road again.

You were recruited into Fairport Convention way back in 1967 and here we are 55 years later. You’re still gigging and still creating music. Why do you think you’ve been able to continue to work in music all this time?

I liken music to herpes. It gets in your blood and there’s no antidote for it. Occasionally it lies dormant and more often it courses through your veins like…..like a virus. You can ice it down, but you can’t cure it. Same as music.

How much do you think you have changed over the course of your career?

As what! Change is a nebulous word. I prefer develop. I like to believe that I’ve become a more patient, compassionate and understanding person and a better musician. Still impossible to live with. What more can I ask?

What are your regrets and what do you see as your main successes over the years?

I have no regrets. I don’t believe in regrets. There are situations where I might have followed a different tack. But all things considered, I’m reasonably happy with the way things have gone. Lots of highs and more than my share of lows, but that’s true for all of us. Isn’t it!

Plainsong has a near legendary presence in English Folk Rock and the early stirrings of Americana in the UK. What are your own feelings about that band and why do you think there’s still strong interest in Plainsong, despite their relatively short existence?

I’m not sure there’s a strong interest. There is a stir whenever Andy and I get together. Plainsong is a great example of something gone wrong, because of youth and naïveté and left to simmer, came back together even stronger. A phoenix of sorts. It’s more about the creative force. Something magical happens when Andy and I work together, even if it is occasional. We love each other’s company. It’s like the story of the farmer and the 3-legged pig. You don’t want to eat it all at one go.

You do seem to have produced some of your best music working with Andy Roberts. Are there any plans for anymore recordings and/or appearances with him?

Andy and I are making a very quick run in December. Five dates, under-the-radar stuff.

We’ll play a mix of solo and Plainsong material. There’s a new book about Plainsong. Published by Route. In Search of Plainsong written by Ian Clayton (he of the fabulous Bringing it all Back Home) and a 6-disc box set just released by Cherry Red Records and we want to show solidarity. After that, it’s anyone’s guess.

I know that, like myself, you’re something of a jazz fan and have made forays into jazz music in the past. What draws you to Jazz and do you have any plans to do more work in that direction?

Since the early 60s I’ve been listening to and widening my knowledge of jazz. It began with Chico Hamilton and has been careering along uncontrollably ever since. These days I listen to an awful lot of Bill Frisell. Will I ever stick my toe in again? I don’t know. Maybe if the right opportunity presents itself, but likely not. In Egbert Derix I found the perfect foil. A pleasing combination of jazz and pop sensibilities and I’m not sure another Egbert exists. We did it. It worked beautifully and now we’re both off on different paths again.

Finally, and thanks for your time, what can we expect from Iain Matthews over the coming months?

Recently I’ve rediscovered the joys of playing solo. I’d like to do more of that. Next year is a make or break year for MSC. After that, we’ll just have to see.