A lifetime searching for life’s sweet spot and honouring his Louisiana heritage.

“The In-Between” is Kevin Gordon’s most distinctive release so far. It is not beholden to the sweet slide guitar and blues rock of 2018’s “Tilt & Shine,” with songs like ‘Fire at the End of the World’ about kids getting high in a small town with small-minded people. Nor is it a revisit to his 2015 album “Gloryland,” and ‘Colfax,’ its 10-minute, coming-of-age story of unexpected darkness. There have been seven years in between “Tilt” and, well … “In Between,” which he started writing before being diagnosed with throat cancer and finished after completing chemotherapy treatments. He jokes that there were no worries about his voice becoming raspy and crackling because it had been that way before the disease took hold.

There is no particular antecedent in Gordon’s catalogue. This one comes off as more direct and visceral, still a guitar record but not one that relies on riffs. Rather, his seventh album is brimming with immense growling textures amid stories that ebb and flow, creating space in the songs as often as they fill it. That approach seems to have emboldened Gordon to let his lyrical idiosyncrasies loose. He’s droll here, and sometimes offhandedly profound as he comes at the stories and sentiments in his lyrics from various vantage points. It is reflective and bemused even but not confounded. In other words, stuff happens and you deal with it, a recipe for many of the characters in the ten songs.

His band is tight and includes long-time producer and guitarist Joe McMahon steering the ship. This is a rock ‘n roll record with songs that look upon his 60 years lived like ‘Coming Up,’ where he sings about The first time I touched that guitar in a rusty shed out on Womack’s farm. The song might be a companion to the boogie-based ‘Letter to Shreveport’ on “Gloryland” where he describes a bus ride to the city in Louisiana’s northwest corner known for its casinos. I rode the bus to Shreveport / When I was 12 years old / My uncle Randy and his friend Hank / Were going to the ZZ Top show.

Gordon tells tales of an old girlfriend (‘Tammy Cecile’), a gay co-worker when he was a dishwasher at a restaurant (‘Marion’) and looking back at diverse sentiments about his father (‘Love Right’). He displays a deep appreciation for literature, which has its roots in a graduate poetry program he took at the University of Iowa and may account for the southern charm and darkness built into his music. He’s gifted in his ability to turn vivid, detailed narratives into gorgeous, bluesy Americana tunes that play out like an epic novel.

All this songcraft was developed through the years and tempered by his brush with mortality that admittedly scared the crap out of him. That experience couldn’t be put any better than what Ernest Gaines, the Point Coupeé, Louisiana author, wrote in his stirring novel, “A Lesson Before Dying”: “Do I know how a man is supposed to die? I’m still trying to find out how a man should live. Am I supposed to tell someone how to die who has never lived?”

Developing a strong appreciation for having the time to reflect on life’s small pleasures is what serious illness offers you in return for its desperate in-between state. Only those of us who’ve walked in Gordon’s shoes truly understand that, but anyone can discover the pleasures of the dramatic tension in his music.

“I can sit around and write songs, but it doesn’t really mean anything unless I can get out and play them in front of people.”

Hi Kevin. I see you are in Iowa touring. Isn’t that where you went to school?

I was in graduate school at the University of Iowa in Iowa City in this program they call the Iowa Writers Workshop, which is a selective grad program for creative writing. It’s mainly two divisions, poetry and fiction, and I was in poetry. I went to college around the area where I grew up in Louisiana, where culturally there’s a lot to be desired in terms of what’s going on in the rest of the world. To get picked to go to that Iowa program was really something for me. It really changed my life, I think, for the better.

Is that something you applied for?

I had the good fortune of having a couple of really good writing teachers my last three years of college. They had been hired from other parts of the country, and they actually knew that there were active living poets and literary magazines being published. Compared to the English instructors I’d had my first two years of college, it was a revelation They suggested that I apply to graduate writing programs, but at the same time, I was playing in bands and writing songs, drinking beer and chasing women. It was a full life.

Being in the advanced program, did that change the way you approached writing songs?

I think it was a cumulative effect. About a year into grad school, I joined Bo Ramsey’s band, the Sliders, and he quickly became a mentor to me at a time when I badly needed one. I would say my songwriting changed stylistically because I was trying to write for that band, and it was much more roots influenced. The band in college, a couple of ’em, were more alternative post-punk. Well, maybe the closest thing to a punk band Monroe, Louisiana had seen.

You didn’t go with the razors cutting up your clothing and studs, the punk look?

There was some of that going on, wild haircuts mostly, but it was an interesting time. It’s such a provincial place. I mean, this was pre-internet. We never really thought about touring outside of our little area. I think we went over to Shreveport and played a couple of times, and that’s about 90 miles west of Monroe. We went to Baton Rouge, which was almost four hours away, but we never thought about going to Austin, Texas or Athens, Georgia.

What was the name of the band?

We started out with an unfortunate name – innocent Victims, and at a certain point I insisted on changing the name to the even more puzzling one, Fragment 36. That was a title of a poem by the poet who went by her initials, H.D. (Hilda Doolittle). That’s high art concepts. I think we were just going through anthologies looking for titles.

Punk rockers tend to be anti-establishment, anti-lots of things. Was the band anti-anything in particular?

I remember just being mean. Our main problem was probably that we were bored. I mean, we would rebel against something if there was something to rebel against, but it was just so flat in terms of experience, that part of the world. I don’t think I heard about the Sex Pistols until three or four years after they came on the scene and went away. I was looking for music that reflected that sort of youthful angst that I had at the time.

You’ve had some health issues which have been documented in the media. What haven’t you been asked about your health?

That’s a hard one. I spend a lot of time talking about my health crisis and recovery from 2022, but ageing is an interesting phenomenon, doing what I do. I don’t get asked about that. I mean, I’m 60 and just glad to be here. My scans have been clear for two years. Last night I was in bed going through an old journal of mine from that time, and I was bouncing back and forth between acceptance and high anxiety. For one reason, it took about two months to get the diagnosis because of a screw up with the first biopsy. When we got the pathologist report back from the first one, even though it was inconclusive, there were some scary words mentioned. I got in my van and drove to New Orleans and basically stayed out of my mind for about three days, just so I wouldn’t think about it so much. Not exactly a healthful response.

It was actually on that drive to New Orleans when I first told people. Obviously, my wife knew about it before anybody. I told my sister first because I wanted her to be with my mother in case my mother reacted poorly. My mother can be, as they say, somewhat high-strung. She has a lot of anxiety, which I’m afraid I’ve inherited. The irony was that I went to all this trouble and my mom reacted splendidly. She took it totally in stride and was completely there for me.

So, have your vocals improved with treatment?

Hah! Unfortunately, cancer didn’t change anything about my voice. I may be a little raspier, a little quieter, and I think that comes from radiation. One of the things that it does is it fries your saliva glands, and some come back and some don’t. It was quite a ride.

Time to change the subject. What kind of music did you grow up with in Louisiana?

My folks were Beatles generation, but their tastes were a little behind. I remember being a little kid and them having get togethers at the house on Saturday nights, having people over and green daiquiris in the blender. Jerry Lee Lewis or Ray Charles was on the stereo, specifically the Ray Charles Country Records.

Jerry Lee Lewis recorded for Sun Records in Memphis. Peter Guralnick wrote an interesting book about that.

I loved everything Sun put out. I went on the tour when I was in Memphis playing in 2018. You start up on the second floor, which is the museum, then you come downstairs and walk into literally what was the tracking room for all those guys. There’s an X on the floor where Elvis stood. They cut all those records live, of course, which is pretty intense.

It’s still rock ‘n roll but lyrically, music has changed a lot since back in the day.

I’ve always admired Springsteen for his songwriting, and a particular period I like is “Nebraska” leading into “Born in the USA,” the B-Sides like ‘Pink Cadillac’ and the song he wrote about Elvis, ‘Johnny Bye-Bye.’ The way that he works with kind of a heightened sensibility about lyrics going into those traditional musical forms really had an effect on me.

Tell me a little about your times with Bo Ramsey. I first came across him when Lucinda Williams came to town with the “Car Wheels on a Gravel Road” tour.

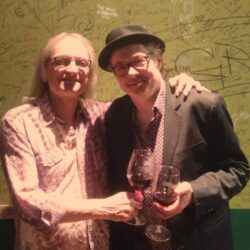

He came to my show this past Saturday in Iowa City. I hadn’t seen him in a couple of years, and we have an ongoing friendship, so it was great. He was remarkable in the way that he carried himself as an artist. Ramsey was always about tone and arranging songs and really giving a lot of thought to a set list. When I was playing with him at the age of 23 or 24, some of that might’ve seemed like overkill. But looking back, I have tremendous respect for that. How he really took what he was doing seriously. Being able to laugh at certain situations that would inevitably happen. We would play an old tavern in these little farm towns, and your dressing room is the beauty shop that’s in the back room. So, you’re sitting in the chairs with the dome that comes over your head, hilarious. But even in that situation, he took a lot of pride in what we were doing.

How did the In-Between Song come to life? What were you doing when you thought of it?

Credit: John PartipiloPardon me while I try to get my caffeinated brain to think about this for a second. It was before I got sick. I remember just thinking about that phrase and that it applied to a number of different things, getting older, not feeling aged necessarily, but feeling older. Life has its limits. The first thing I wrote down was what became the first verse, and trying to acknowledge being older and this idea of not original sin necessarily, but that as soon as you’re born, you lose something, which may be a bit of an overstatement, but I thought that was interesting, the image.

Well, in a biblical sense, you lose your innocence as you’re being born.

I was considered what was called a good kid back in the day, which meant that I feared my elders enough to act appropriately. But I had what I still consider to generally be goodwill towards others. I wasn’t prone to misbehaving necessarily, but as you get older and become an adult, there are things that come up that test you. I was thinking about having been someone who had been touring for 30 years and for whom things had certainly gotten a little better, but had not taken off in an upwardly mobile direction as they say. At a certain point, you do this long enough and what else are you going to do? I mean, I have a side hustle as a small-time folk-art dealer, but geez, couldn’t I come up with two more difficult ways to generate revenue for the household?

Let’s go with ‘Simple Things’ next. 14 months since I’ve seen a smile crease the corner of your eyes.

That started in 2020 as a response to what was going on with the lockdown. At first, I was just thinking pretty much about my own lot, so to speak, that I wasn’t touring and it’s what I missed. But the more I thought about it and worked on it, the more it became obvious that it wasn’t going to be a commercial song. Then I began to think in different terms, not as a touring musician, but as a human being. What do you miss when you can’t go anywhere? You can’t see anybody? Is the refrain my favourite thing I’ve ever come up with? No. That’s the cruel irony of the thing, I guess. But it was sincere, and I really did miss all that stuff. I mean, I can sit around and write songs, but it doesn’t really mean anything unless I can get out and play them in front of people.

What about ‘Keeping My Brother Down’?

That’s actually one of the older songs on the record, and I started writing that in 2014. It was when Michael Brown was killed and the riots in Ferguson were going on. Then shortly after Eric Garner died on Staten Island. It was just a response to that, and I immediately thought about Emmett Till and went and researched details surrounding his murder. Decided to just lay it out. But I’ve had a hard time with that song because the violence seems so excessive and gratuitous. But at the same time, I felt like it was an important thing to not – What’s the quote by the Japanese filmmaker? – “Don’t avert your eyes.” I’m not sure that’s an exact quote, but I don’t turn away from what’s there. For the longest time, the song’s title was ‘Keeping the Black Man Down,’ and it was only a month or so before recording it that what I would argue would be a better title came up and drove home the obvious point that we’re all human.

‘Love Right’ seems to be a response.

That was an idea I had while driving around town, like running errands, and they hardly ever happen that way, but I had that funny idea of getting your love right and just started thinking about the different ways that could be applied. The funny thing about parking with your girlfriend in high school, the vehicle you’re in presenting its own obstacles, but then what becomes of the girlfriend? I still communicate with her occasionally on Facebook, but the more I started writing that song, the more it seemed to have to do with my dad and my relationship with him, and being able to say some things that I had never said before. My father and I are still physically and emotionally distant, but the older I get, the more empathy I have for him. You start thinking about what your parents were doing at the age I’m at now. It was dealing with some leftover things.

‘Tammy Cecile’ – What’s better – hook-up sex or make-up sex?

I think the verdict’s still out on that one. I had been wanting to write something about her for a long time. I was working on that song in early 2020. I remember I was at the Songwriters Festival in Florida, and it’s always a great place to go in January, One of the great things about that festival is you have a lot of free time, and I was staying in the nicest garage apartment I’ve ever stayed in. It was very comfortable. I could make as much noise as I wanted to, which generally when starting songs that’s an important thing, knowing that I cannot be heard. I started just thinking about her, the name and how funny it was, but also back to that relationship, which was a typical college romance. Except for the fact that although we were both these non-conformist kids, the first thing she wanted was a wedding ring, which terrified me. So overall, it was a way of processing that relationship and extending some empathy towards her, which I probably did not have at the time that relationship ended. Even though it was breakup sex; it was complicated. I have no idea what she’s doing now.

Many times you don’t know what happens to people after they go out of your life. It could be anything. Let’s go with ‘Coming Up.’

That song came from a fragment of an idea that I had 10 or 15 years ago. I had a little recording of it and a melody, a chord progression, the arrangement, and I had that title. I just didn’t have lyrics. When we came around to the second batch of tracking sessions, I thought let’s see if I can finish it. By the second tracking session, I knew I was sick, treatment had already been scheduled, so there was a certain urgency there. I wanted to try a couple of things we hadn’t recorded before the first round, so then it became this little puzzle. What are the words? It forced me to finish the song. I’d invested time and money and effort into a track and needed to finish it.

Credit: Jacob Bickenstaff

‘Destiny’ must have been a tricky subject for you.

You can say that again. On the face of it, it’s about an old relationship, but it expands a little bit and becomes more of an idea that what you think is going to happen isn’t going to be what happens necessarily. I’m really glad we recorded that because it has become a fun song to do live. It’s also one of the shorter songs I’ve ever recorded, and I take a certain Ramones fan kind of pleasure in that. I remember thinking about it lyrically as maybe referencing a shorter version of a mid-sixties Dylan song in the way that the rhymes kind of fold over on each other deliberately. There’s a playfulness to it.

Hearing your song ‘Marion,’ I couldn’t help thinking. There’s a record by a songwriter named John Forster, nothing to do with Robert Forster from the Go-Betweens. The title to this album was called “Entering Marion,” which was of course a play on words because he came from a Massachusetts town named Marion, and the girlfriend is Marion. You get the idea.

Oh my God, that’s funny. Well, my song is based on an actual person I knew. As the song says, I worked in a restaurant with him when I was 15, and he was just one of this incredibly eccentric group of people who worked at this place. In this small southern town, you’d have these people show up to work who had just sort of dropped out of the sky from Reno or West Hollywood, or fugitives probably, who knew? But Marian was a Louisiana native. He came from a little town, the same parish as my stepfather, Franklin Parish, southeast of Monroe. It didn’t stay really true to his life. It wasn’t that he was gay; in reality he was, I guess what they would call now pansexual, but basically just non-committal, one of those guys that had a feminine quality about him, but he wasn’t gay though he worked with a lot of gay men.

It was my first experience working with gay men, and my stepfather managed the restaurant. It was an eye-opening experience for me, very good for me, I think. But years and years later, I had heard that Marian had taken his own life, and I just thought back to what a repressive time and place that was in that part of the world and how hard it must have been to be anything other than straight up redneck male in that world. Even though Louisiana in the cities like New Orleans was way ahead of its time, there were significant gay communities that were functioning under the radar, so to speak. I think there are other songs to be written about that experience, if not a novel.

Credit: Grant Frashier

‘Catch a Ride’ seems to be about a commitment problem.

That was a song that I wrote right before the second round of tracking sessions. I knew I was sick and it was almost kind of like a gospel thing, even though my religious persuasion is probably one of, how would I describe myself? Hopeful, agnostic.

Right. Don’t want to commit.

I do have a faith in things. I was kind of driven insane by extreme Christianity. When I was in college, my stepdad and mom went to a holy roller church. And man, I had a hard time with it. If I would come home from college on the weekends, they would make me go to church with them. They lived in a little country town, and I was kind of terrified by things I saw and heard, but also quietly amazed someone’s faith can make them do these things. Speaking in tongues and rolling on the floor and all these sorts of physical manifestations of spirituality. I knew it wasn’t my place. I didn’t ever feel comfortable in that situation. I think artistic people have by nature a more complex relationship with anything metaphysical. I don’t know where that phrase came from, but I just kind of riffed on it and had a progression in my head.

We’re down to ‘You Can’t Hurt Me No More.’ It’s like a biblical genesis maybe of a love affair. I remember seeing this series on TV called “Fleischman in Trouble,” and it was all about the dissolution of a romance, how it started, and how they dealt with when it began to fall apart. But to your song.

It’s related to the destiny song, how you go into things feeling hopeful and positive, and at the end feeling or trying to fool yourself into believing that this person who has affected your life so tremendously no longer has power over you.

There’s an acceptance at the end. You can’t hurt me no more. I’m thinking the five stages of grief, which I’m sure you’re familiar with having gone through cancer, could be applied to a personal relationship, a love relationship. You pretty much go through the five stages of grief during a breakup, especially if you are the one getting dumped.

And then the cruel irony is running into this person, even virtually online, it can bring back those negative feelings. It’s hopeful but at the same time, acknowledging the possibility that our hopeful protagonist can be damaged again. That was more of a pop song than I’m used to writing, and that’s why I wrote it with my friend Kim Richey. I already had the melody and the chord structure and some of the words. I could hear someone like her sing that song. She helped me finish it. That one’s been fun to do live. A lot of people have responded to that song in very powerful ways that I did not expect.

There are a couple other songs not on the new record I’d like to ask you about, one being ‘Cadillac Blue’ on Shemekia Copeland’s album.

I co-wrote that with her manager. He emailed me and said he had these lyrics and would I try to write some music to them? Nobody had ever approached me like that before. But I said, sure. because to me, it sounded like the hard part was over. He had the words, so all I had to do was find something to drive those words along. It was an interesting way to work.

Was it important to visualize who would be singing the song?

Yeah, and I was familiar with her work. She had cut another song of mine on an earlier record, which was one of the most unlikely covers. So, I had a familiarity with her.

Wonderful artist. Her previous two records made my best of lists in those years.

She is wonderful. I’ve opened a couple of shows for her, and I really dug the live show because she comes out and starts with a gospel thing. She’s playing the tambourine, and then in the middle of the show, she breaks it all the way down to her and one of her guitar players playing slide. So, it still retains this very traditional rooted foundation while exploring new ground thematically.

The other song I wanted to ask about is ‘Flowers’ off the “O Come Look at the Burning” album. The first verse grabs you immediately: Reverend John was an upstanding preacher man / Sang tenor in a gospel band / They were driving home on a Saturday night / Last thing he saw was a drunk’s headlights.

Interesting choice. That song started as I was kind of, triggered isn’t the right word, but I was listening to Leadbelly at the time, and he has this kind of funny song about driving. Oh God, what’s it called? I’m going to have to look it up. It’s been so long since I’ve thought about it, but anyway I had a friend in Memphis who’s a photographer and had done a series of photographs of roadside shrines. He had gone all over the West and taken photos of roadside shrines where people had been killed in auto accidents. The first verse is very personal in a way in that the preacher is actually …. boy, how do I explain this without getting incredibly complicated?

There was a church diagonally across from the house where my parents and I lived in Shreveport. And to get me out of the house, my parents signed me up for vacation Bible school. That guy was married to a woman who after he died, married my grandfather, and I had this preacher’s church as a kid before his then wife even knew my grandfather. It was one of those things. The grand climax of Vacation Bible school is that you got baptized and or saved, whatever your particular needs were in their eyes at that point. I went to the service by myself. I was standing right next to the preacher’s wife who would later become my step-grandmother. And when those of us who were to be baptized were called up to the altar, I wouldn’t go. I was terrified. That always stuck with me. Years later, the preacher was killed in a car accident.

I wonder if Irma Thomas knew any of that story?

I don’t think so. I met Irma one time after she had recorded the song, but we never were in the same place long enough to talk about it. My late friend, the songwriter David Egan, actually handed her that song, and I’m eternally grateful to Dave for doing that when he didn’t need to. I mean, he was trying to get his own songs on that record, and he did get three or four of his songs on.

Why did Willie Dixon’s death move you to write a song?

I was driving through that part of the country on the day that he died, and I heard it on the radio. I was listening to NPR or something, and they announced that he died, and I knew that he was from Vicksburg. So I just started thinking about his life and all these details started coming up, the names of the bands that he was in, and before he became basically the staff songwriter for chess and the house bass player, and the whole thing about chasing little brother Montgomery around when he was on the back of a truck playing piano. I mean, just the visual of that, I found it impossible not to write about. So that’s where that came from. That was an early song.

Joe McMahon has worked with you quite often. So tell me a little bit about Joe McMahon. Tell me a story about Joe. What’s he like?

Well, he’s a difficult person to get to know. He is the typically emotionally repressed male, but he’s also a fantastic guitar player. I met him through a mutual friend, also a great guitar player, who at the time I met Joe, we were all living in Nashville. I kept asking Buddy to play guitar with me, and Buddy kept turning me down. I understand that now. He wouldn’t have been right for my gig, but Buddy suggested Joe and I called him, and Joe for some reason, agreed to do the gig. I sent him some songs and we started playing together and soon became fast friends and allies.

He had gone to Berkeley Music School in Boston for a year, and he had moved to Nashville to take a gig with Jo-el Sonnier, the Cajun accordion player, who at that time had a major label deal with I think MCA in Nashville. And through Joe’s time in that band, that’s how I got to know two other guys who were playing with Jo-el, the drummer, Paul Griffith and bass player Ron Eoff. So very quickly those guys became my band, and it was just a great group of kindred spirits. We all came from either Arkansas or Louisiana and had a great respect for music we heard growing up there. So it made a lot of sense. Well, Joe knows probably better than anybody where I’m coming from aesthetically and every record he tries to drag me into not another direction, but tries to make each record sound different from the last one. He’s really talented in that way.

Living in East Nashville, there is no shortage of world class musicians to work with. How do you go about choosing who plays on your records and in live shows?

I’ve been kinda predictable over the years – if something works, why fix it, especially if the sound continues to evolve and each record is different from what came before it? Joe McMahan knows me better than anyone; I have trusted him implicitly to know where I’m coming from, and to have good ideas about how to move the thing forward. With the live band, things tend to go in cycles: drummer X will be available for several months, then gets a road gig and is gone, though bass player Ron Eoff has been in the band most of the time since 1994. It definitely forces you to be stronger as the front man. You become the central identity instead of it being about a band. Inevitably schedule conflicts come up, and that’s a time when I’m very grateful to be among this large community of good players.

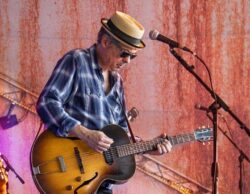

KG with Sonny Landreth at City Winery, Nashville

Do you have a musical bucket list? Things you want to do?

Creatively, I want to make a record in South Louisiana with a certain cast of characters who live down there. I don’t know musically what that would be like, and I don’t know what the songs would be, but it just sounds like a hell of a lot of fun. My friend CC Adcock from Lafayette, he’s a great guitar player and just all around ornery character. Sonny Landreth is in Lafayette, of course, and Louie Michot from Lost Bayou Ramblers. Probably New Orleans people, too. Otherwise, I’d just like to be a successful touring artist, to be on a bus and or flying instead of trapped in a minivan for eight hours a day. But I enjoy it on whatever level I’m on.