A love for historical recordings leads Li’l Andy to create a new history.

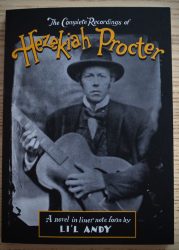

I recently reviewed Canadian singer/songwriter Li’l Andy’s mixed media project, “The Complete Recordings of Hezekiah Procter (1925 – 1930)” in which Li’l Andy wrote a novel about an early 20th century country musician and then brought his character to life through a set of recordings that mimicked the style of that time. I found it a really fascinating project and wanted to hear more about how it came about and the inspiration and thought processes behind it all and, thankfully, Andy was more than happy to satisfy my curiosity.

What was the starting point for this project. How did it all come about?

My dad inherited a gramophone from the family farm — the kind you wind up and has a cabinet for storing records. When we were kids, my brother and sister and I would wind it up and play 78s, like ‘Turkey in the Straw’ or ‘Hallelujah, I’m a Bum’. It was the only “stereo” we had in our playroom as children. We probably had 40 or fifty 78 records. But the record collection that my great-grandfather or great-grandmother bought wasn’t (understandably) “cool” by record-collector standards: it was mostly fiddle tunes or hymns—exactly the kinds of records you’d imagine Canadian Protestant farmers would buy during the Depression. When I was 11 or 12, I got into The Carter Family and Leadbelly and buying boxsets—anything that Yazoo or Bear Family or Smithsonian Folkways would reissue.

I loved how historical and archival those box sets were. I’d listen to the music while reading the liner notes and got sucked in as much by the music as those artists’ stories, the mythologies that built up around them. What made them burn out and fade away so young, so sadly, so mysteriously? That made me wonder: could you create some kind of über-roots musician, that kind of untrained, self-destructive genius who makes a handful of great recordings, then disappears from history so that 78rpm collectors and archivists obsess about him?

Where did Hezekiah come from? How did you come up with his name? Also, what was your inspiration for the support characters in the book – where did they come from?

Hezekiah popped into my head as a character from reading the liner notes and histories of country and blues singers as a teenager. When you read those stories, there are so many tropes that recur again and again, that we now expect in the biographies of early 20th century Roots musicians: a childhood spent in rural poverty, a religious introduction to music, a brief period of success in recording, and then a sudden disappearance or tragic death. I wanted a character that would draw attention to the proper “script” we expect a country singer to follow before we consider him authentic.

Regarding his name, there was a habit in the South at the time of picking a first name from pretty much anywhere in the Old Testament and then picking a more common, Anglo-Saxon name as a person’s middle name. Hank Williams’ real name is “Hiram”, which his mom or dad picked out of the Bible, and then someone in his family or at a birth certificate office misspelled it and made it “Hiriam”. So, I drew from that and took “Hezekiah” from the Second Book of Kings. Procter means “right-handed” in the tradition of medieval heraldry.

The support characters are all based on the real musicians I made this album with: the guys from Sheesham and Lotus & ‘Son, who became Hezekiah’s “Hash House Serenaders” in the novel, and Brad Levia and Julia Narveson from The Ever-Lovin’ Jug Band. As I wrote the songs for them, I melded each real musician with the character types of early 20th century country musicians. Julia’s character — Euphemia Middle, who in the novel is Hezekiah’s sister-in-law — is a foil for Hezekiah, the kind of creative musician who sticks to her principles and ultimately pays a huge price for it.

Tell us a bit about the various photos and portraits you use in the book. How did they come about?

When my “Li’l Andy” band was on tour in the Yukon a few years ago, a guy came up to the edge of the stage and said he was a tintype photographer. Dawson City seemed like the kind of place where you’d meet someone like that, with its history of the Goldrush and wooden sidewalks. He said he’d like to take tintype portraits of us, and that was an invitation I couldn’t refuse.

When I looked him up, I realized he was a serious visual artist named Paul Elter, just as talented at painting as at old-fashioned photography. When I told him the concept of Hezekiah, he became an ideal collaborator in every sense: getting into the character and helping me formulate what he looked like. Then he said: “You know, all those old photo studios had a bunch of canvas backdrops that were hand-painted, to act as scenery for the photos. I could paint one if you wanted!” So, the painted image you see behind me and the Hash House Serenaders on the album cover is a 9-foot-by-15-foot colour painting that Paul made after reading the novel and incorporating elements of it. He’s the kind of artist who really does not care how long a process takes if that’s what is needed to get it right.

In the novel, you’re quite scathing about some of the practices of people like Peer and how they profited at the expense of the artists. Was this something you intentionally wanted to include in the novel?

In the novel, Peer is just a stand-in for the music business. He was an opportunist and a racist, for sure—but he was also a typical man of his time, an American huckster capitalist. What intrigued me about Peer was how he and the other men who recorded early country and blues music created those genres by shoe-horning artists into pre-conceived ideas of Blackness and whiteness, pre-conceived ideas of rural poverty or musical tradition.

Music fans always get into folk, country, blues or jazz thinking they’re discovering something “pure”, something more noble and essential than commercial pop music. An entire generation of mostly white 78 collectors fell in love with Blind Lemon Jefferson, Charley Patton, or Robert Johnson by romanticizing this idea that what they were hearing was a poor Black man pouring out his sorrow — and, by extension, the sorrow of his entire race — on record. But when you actually go back and read the history, you discover that those singers had a much more diverse, and less “pure”, musical knowledge than they were presenting on their recordings. Robert Johnson used to play Bing Crosby covers at his shows, and Big Bill Broonzy was just as talented at playing hoedown fiddle as he was on guitar! But that’s not what the white guy running the recording sessions wanted to hear. He wanted to hear Black artists play “black music”. So in the novel, Hezekiah starts out playing jazz and blues music, until Peer asks him to play “white” songs, meaning something more “country”. And Hezekiah — because he wants to get paid and is an opportunist himself — goes along with it.

Using Peer in the novel allowed me to think about these ideas we have about “purity” and “commercialism” when it comes to celebrating music. There is no “purity”, there is no traditional American music style or genre that is untouched by commercialism. But in the Americana, or Blues, or Bluegrass community it’s a myth we always fall back upon, be it framed in terms of “The Outlaw country music was pure, and Nashville had sold out!” or “Hank Williams was authentic, and The Grand Ole Opry is a sell-out”. The fact that so much amazing music could be created under that commercial system is what interested me. And I think that the sooner we stop thinking in terms of “purity” and “authenticity” when it comes to music and art, the closer we’ll get to the truth.

The music on the album(s) is very different from your usual Li’l Andy recordings. How difficult was it for you to write in that old-time style? Did you enjoy it and what did you learn from it?

I’ve been writing songs since I was around 11 years old, but when I was 17, I wrote my first bona-fide country song. I didn’t know where it came from: I wasn’t a country fan at that time. But I had grown up listening to the Hank Williams and Johnny Cash records in my parents’ record collection and was made to listen to Top 40 country by the driver of our school bus every morning and afternoon. So, it was a tradition I grew up with.

The music I’ve been working on with my “Li’l Andy” band for the past 20 years has always been rooted in country music. But it just so happened that the fiddler and pedal-steel players in that band — Joshua Zubot and Joe Grass — are just as well-versed in playing free jazz or experimental music as they are at, say, Bluegrass. So, our music will go from pretty classic honky-tonk to weird, experimental soundscapes with my voice floating over it. That’s just how they change and interpret the songs that I write.

I wrote most of Hezekiah’s songs at the same time I was writing the songs from my last “Li’l Andy” album, All the Love Songs Lied to Us. I’ve always been suspicious of the idea that singer-songwriters have to write as their “real” selves, that you have to wear your heart on your sleeve and write about your inner turmoil or break-ups or whatever. I think a lot of really bad songs have been written that way since the singer-songwriter tradition became the default genre for the musicians we call songwriters. I’ve always felt that, paradoxically, better songs were written by those songwriters who were writing for commercial genres, like the Tin Pan Alley writers or people like Cole Porter or Duke Ellington. So, writing “as” Hezekiah was a challenge I set myself: could I write made-to-order songs for another genre? Could I get away from this singer-songwriter template and write “as” someone else?

Where did you source the Wire Recorder you used and what were your impressions of that form of recording? It does convey a great sense of atmosphere, though it becomes increasingly difficult to listen to after a while. Would you use it again?

I like to approach every album I make as an experiment in recording. When my “Li’l Andy” band did ‘All Who Thirst Come to the Waters’, we brought a whole studio into a cathedral in Montreal and placed microphones everywhere: in the pews at the back, at the rafters, to make sure we could capture different reverbs. When we made ‘While the Engines Burn’, it was an experiment with live, off-the-floor, analog recording. “Can we make an album that sounds like Neil Young’s Harvest in the 21st century?” was our thinking on that one.

When the idea of making a fake retrospective box set for Hezekiah came to me, I realized: “I have to make these recordings sound old!” Recording them digitally — on ProTools or whatever — would’ve ruined the effect. Even recording them on analog with multi-tracking would have ruined the effect. I wanted the recordings to sound authentic to the story I was telling of this evangelical, 1920s Marxist country singer from the era when commercial recorded music was just starting. So, it started me on a wild-goose chase to emulate that sound. I contacted a lot of early audio-recording enthusiasts from around the world: I wrote to 78rpm record enthusiasts in England and Germany who still cut to wax or lacquer. But… nothing I heard sounded really good. I think that recording on that gear is a lost art, sadly.

At practice (with my “Li’l Andy” band) one day, I was complaining about it to my drummer, Ben Caissie. And he said, “You should try a wire recorder!” I hadn’t heard of a wire recorder, but Ben explained: “It’s this machine they made in the 30s. It records on a reel-to-reel like a tape machine, but instead of tape spinning by, it’s this razor-thin band of steel wire. It’s steel, so it doesn’t degrade and become unplayable over time like tape.” That sounded promising. But we didn’t have one. Ben set up a Kijiji alert for “wire recorder” and after about a year, he saw one listed for sale in Quebec City. That night he hops in his car, drives to the address the guy gave him over the phone, and arrives at this huge cathedral. The guy selling it was the caretaker of a Catholic church and they’d used the wire recorder to record sermons in the 30s and 40s!

Ben bought their 1937 Webster-Chicago wire recorder, and when he was leaving, the caretaker said: “Here, you might as well take these too!” and gave him dozens of wire reels to record on. So that’s what we recorded the takes on: we taped over hours of sermons to make this album. Between takes, we’d listen to the voice of a Roman Catholic priest sermonizing in French as we cued up for the next song.

Why did you decide to release two versions of the album in the box set. What point were you making by issuing one wire recording and one using modern technology?

I find that people think of technology as something transparent, that as the digital world gets better and better, even more “real” than our real world, it’s becoming more true to what the source is. And I think that’s a dangerous idea. I wanted to actually show whoever bought this album that the technology we use to record sound changes the character of what we record, that any technology we use puts a frame and a constraint around what we use it on. So, in giving people two versions of the exact same musicians, laying down the exact same take of the same song but on two different recording set-ups, I’m asking them: “Which one sounds better to you? Or “more real”? The wire recorder, which sounds like an old 78, or an analog tape version that’s cleaner? Which one sounds truer to the idea of old-time country music? Interestingly, I find most people prefer the wire recorder versions: they fit what we think old country should sound like.

Is this the end for Hezekiah, or do you plan to write/record more? I notice that the album is ‘The Complete Recordings 1925 – 30’ and that Hezekiah has a habit of using aliases; can we expect more from him in future?

Is this the end for Hezekiah, or do you plan to write/record more? I notice that the album is ‘The Complete Recordings 1925 – 30’ and that Hezekiah has a habit of using aliases; can we expect more from him in future?

I could make more Hezekiah recordings: there’s at least ten other songs I wrote “as” him, or for him, that I left off this album simply because I thought its scope and length was already getting close to being intimidating for the listener.

I feel that Hezekiah’s story has been told, and that, as a recording, songwriting and general meta-fiction experiment, it’s all there in a tidy little package. I’d rather focus on making the other albums in my brain than reopening the Hezekiah can of worms. I have ideas for other concept albums, or what I’d call meta-fictional albums, and I need to save my money and time to make those.

You’ve performed these songs to a live audience as Hezekiah. How did that work out?

As this project got bigger and bigger, I realized I’d basically have to become an actor on stage in order for the music to come across: there was no other way than to be Hezekiah while I played his songs with his fictional band. Which was terrifying, because I am not an actor—my sister and her husband have been actors and theatre directors for 20 years, so I am acutely aware of how I’m not an actor.

That meant I had to prepare a lot for the stage show: writing the speeches that I say between songs, imagining how Hezekiah would move and comport himself on stage. So, in the rehearsals, I practice the in-between song banter while the guys from Sheesham and Lotus & ‘Son watch and tell me what works and what doesn’t. We create set pieces between the four of us that are sometimes like vaudeville routines or like socialist union rallies from the 20s. We work on that as much as the music.

What did you learn, personally, from this project?

It’s made me think of the messy quagmire of “authenticity”, this cult of authenticity which we totally fetishize in folk music. It comes up every time someone questions whether or not Gillian Welch can or should be writing Appalachian-style songs, because she’s from L.A. instead of being from Kentucky or rural Tennessee. Or every time a music fan spouts some conspiracy theory that Levon Helm must have written all those great songs about the South that The Band did, because he’s from Arkansas, and Robbie Robertson was just some kid from Canada who’d read a lot of books.

We shouldn’t be asking: “Is this artist the ‘real deal’? Do they have the correct life story and background to play this music?” We should be asking: “Are the songs good?” Particularly today, when “authenticity” is just another marketing strategy, be it in country music or on Instagram.

You’ve recently received some awards in your home country of Canada. Were they for this project? Tell us a bit about them.

Well, I was nominated for 3 awards, but I forget when the winners will be announced.

They were for “Songwriter of the Year” and “Traditional Singer of the Year” at the Canadian Folk Music Awards. And then “Best Country Album” at the Gala Alternatif de la Musique Indépendante du Québec, which we could translate for those not knowledgeable of the Quebec music scene as “The cool, non-industry-dominated awards for artsy people who actually care about music and go to shows”!

What are your future plans? What is your next recording project and are there more books in the planning?

Right now, I just want to play as Hezekiah with the guys in Sheesham and Lotus & ‘Son as much as possible. I started out playing acoustic music, and this project has unexpectedly been a nice return to that. There’s a real honesty and clarity in playing only acoustic instruments on stage. You know that whatever power you’re putting out there is your power; it’s not the volume of an amp, it’s not the novelty of effect pedals. And audiences sense that even if they’re not musicians themselves.

I’ve started another novel, but I don’t know where it will go. It’s not about music or musicians at all. But writing this book in the middle of a pandemic taught me that I really like the intense discipline that’s required for writing novels: that routine of waking up and writing until you’ve produced a certain amount of words, what Samuel Beckett called “ass-on-chair”.

I have my next “Li’l Andy” album written, and its starting point was a concert film I did for the Suoni per il popolo festival here in Montreal, where we added two background singers and a string quintet to the core honky-tonk band of musicians I usually play with. (it’s on YouTube, if you’re curious: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9i-64sJhsg )

Playing with the scope, the kind of cinematic power, that an 11-piece band like that give you is pretty intoxicating. So the next album is based around that. But I certainly won’t be able to capture it on a wire recorder. After years of experimenting with that, I’m pretty damn eager to get back in a big, fancy studio with a two-inch tape machine and start playing around with that!

Is this the end for Hezekiah, or do you plan to write/record more? I notice that the album is ‘The Complete Recordings 1925 – 30’ and that Hezekiah has a habit of using aliases; can we expect more from him in future?

Is this the end for Hezekiah, or do you plan to write/record more? I notice that the album is ‘The Complete Recordings 1925 – 30’ and that Hezekiah has a habit of using aliases; can we expect more from him in future?