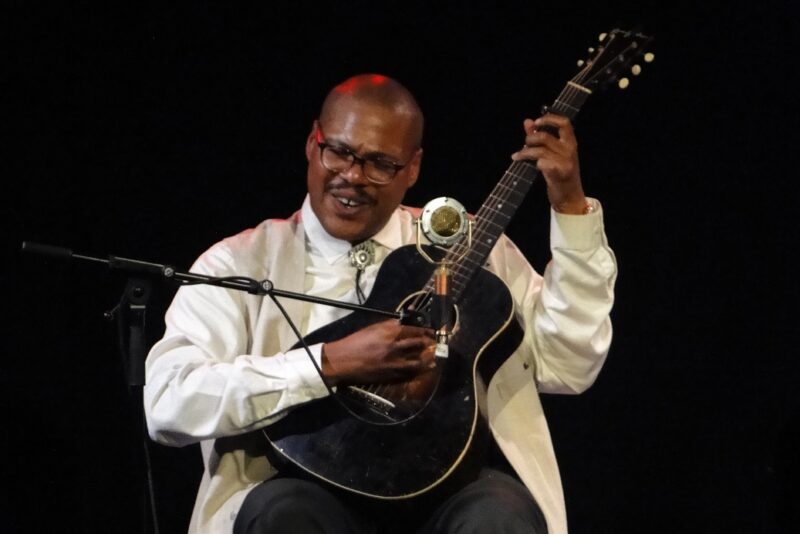

New York-based Jerron Paxton, a multi-instrumentalist, caused a sensation on Later … With Jools Holland last October, but the typical description of him as an acoustic bluesman is surely inadequate. In fact, his music includes a range of American popular music styles, including not only blues but also old-time music, gospel, ragtime and folk, not to mention songs from the Great American Songbook. But whatever the style, and whether playing acoustic guitar, banjo, fiddle or harmonica, Paxton’s playing at this remarkable gig was masterful and with his engaging personality and humorous anecdotes, he captivated the audience.

On Piedmont bluesman Julius Daniels’ ‘Ninety-Nine Year Blues’, a song which has been covered by Jim Kweskin, Johnny Winter, Chris Smither and others, the lyrics describe a brutal punishment being handed down by a judge to a black miscreant. Throughout the set Paxton sang authoritatively and expressively, and the relevance today of the song’s depiction of injustice and racism in the American legal system could hardly have been missed by anyone in the audience.

Contrastingly, Paxton performed, again on acoustic guitar, Irving Berlin’s ‘Sunshine’ with disarming insouciance. Among the other non-originals were ‘The Arkansas Traveler’, an old-time Appalachian banjo tune which Paxton played beautifully; another banjo song, the Uncle Dave Macon-associated tearjerker ‘Poor Old Dad’ (“You’ve made your poor old mother weep from midnight until morn / You’ve made your poor old father curse the day that you were born …”) and Clara Ward’s gospel classic ‘How I Got Over’, with Paxton now playing slide guitar, a moving song of faith and belief in a better life to come, in heaven.

Paxton’s originals included ‘Tombstone Disposition’, a song replete with traditional blues imagery and language; ‘Things Done Changed’, a break-up song but a notably quirky one (“Love you, baby, love your lover too,” sang Paxton), and ‘What’s Gonna Become Of Me’, a lyrically bleak song about a mean, mistreating woman, featuring intricate banjo playing.

Some of Paxton’s chat between songs lasted nearly as long as the songs themselves, and, endearingly, on occasions, he laughed even more raucously at his own humour than the audience did.

At times, indeed, Paxton needed his sense of humour for his banjo often resisted his best efforts to tune it, and his harmonica at one point suffered a broken reed, forcing him to abandon ‘Little Zydeco’. But Paxton’s charm merely made such mishaps seem like part of the fun, and the standing ovation at the end of the performance was the least that this master entertainer and master musician deserved.