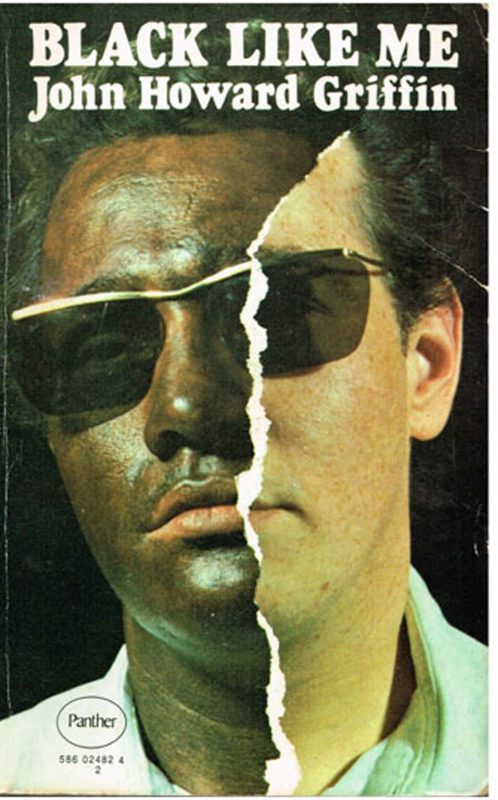

Blackface or bravery – you decide.

‘Rest at pale evening / A tall slim tree / Night coming tenderly / Black like me’ – from, ‘Dream Variations‘ by Langston Hughes

‘Rest at pale evening / A tall slim tree / Night coming tenderly / Black like me’ – from, ‘Dream Variations‘ by Langston Hughes

John Howard Griffin disguised himself as a black man by the use of medication, sun lamps and dye. He travelled through New Orleans, parts of Mississippi and into South Carolina and Georgia over a period of weeks in 1959. He did this in order to experience, as best he could, the life of a black man. He wanted to test the idea that black people:

‘led essentially the same kind of lives whites know, with certain inconveniences caused by discrimination and prejudice’.

Not surprisingly he discovered that this was a self-serving fantasy propagated by those who touted the idea that the rights agenda would only upset what was a happy and ordered social apple cart. Griffin discovered that everyday existence was made deliberately difficult for a black man, who might spend a good part of his day looking for somewhere to eat, drink, rest or use the toilet. He also discovered that the all-pervading and malign influence of segregation hung over him to the point where it caused a near breakdown – even in such a short time.

Having completed this experiment he wrote a book about it, ‘Black like Me’’ which sold a phenomenal 10 million copies (12 million by some estimates) and which helped bring out into the open the festering sore of parts of American society. The project was underwritten by Sepia magazine, and articles appeared there under the title, ‘Journey Into Shame’, before the full account was published in book form in 1961. In 1964 the story was made into a film and a 50th-anniversary edition of the book was published in 2011. Surprisingly for a book written 60 years ago, there are few cringe-worthy moments (though I am tired of the modern dubiously virtuous points scoring one-upmanship that is sometimes on display around correct and incorrect use of language). That said Griffin does occasionally let himself down with phrases like,

‘The incredible vulgarity of highly amplified Hillbilly Music’.

It was not that anyone terrible thing happened to Griffin. There were plenty that could have and one kind soul explained to him how the swamps could easily accommodate the bodies of any trouble makers. What strikes is the overwhelming oppressiveness of segregation, which seemed, in the end, to drive Griffin to that near breakdown – he just couldn’t stand it any more and had to get away. This led to a period where he oscillated frequently between his black and white identities.

Griffin was born in Dallas in 1920 and studied medicine and music in France with the hope of becoming a psychiatrist. At the beginning of the Second World War he is said to have been the only American involved in the ‘defense passive’, wherein he helped some of those persecuted by the Nazis in Germany and Austria get out before the fall of France. Eventually, these activities led to his needing to leave quickly, whereupon he joined the American Army Air-force as an intelligence officer and was badly wounded twice – causing a state of temporary, though extended, blindness. He recovered his sight in 1957 two years before embarking on the journey he described in, ’Black Like Me’, and the book can be read as a reaction to the lessons he learnt while sightless. He later wrote,

“The blind, can only see the heart and intelligence of a man, and nothing in these things indicates in the slightest whether a man is white or black.”

The book is profound but also what one might call a relatively easy read which sometimes, unsurprisingly, grips like a thriller. It has no pretensions to high art and is a relatively short account of Griffin’s experiences. I was introduced to it as part of my A-level history course, the teacher of which was something of a character. He told us that we would know his brother – seen at the beginning of, ’Match of the Day’, being escorted from Upton Park. And it wasn’t because he was blowing bubbles.

One of the first impressions the book leaves is the kindness shown by other black people toward Griffin – those with least seemed to share most and he was well looked after by a succession of characters, particularly so after he disclosed his plans. In contrast whilst he thought he might be able to judge the book by its cover he became increasingly aware that as pleasant as a white man might appear he could be as racist as the next. Having received a lift from what appeared to be a decent sort of white man Griffin was told that no black woman would work in his business unless she had sex with him. His parting comment was,

‘I’ll tell you how it is here. We’ll do business with you people. We’ll sure as hell screw your women. Other than that, you’re just completely off the record as far as we’re concerned. And the quicker you people get that through your heads, the better off you’ll be’.

The sexual prurience is astonishing as Griffin, whilst hitch-hiking, is asked about the size of a black man’s penis, whether he craves white women, and being let know that black women are easy prey for white men. Whether an attempt to get him to expose his penis is generated by his blackness is not clear – but Griffin is left feeling that, as a black man, he is picked up like, ‘a pornographic book or picture’, with no question too outlandish or insulting to be asked.

Interestingly, he found the older generation the most alienating as he experienced what he called, ‘The Hate Stare’, – often delivered for no better reason than he existed and happened to be in eye-line. Griffin is far from suggesting that all whites are antithetic to black people – but he sets little store by those who don’t step up to the mark but then make a point of apologising for their fellow whites behaviour after the fact. I do wonder how difficult life would be for someone prepared to voice disapproval in a culture where prejudice was ingrained?

At the off Griffin recounts how the black man, who used to shine the shoes of a certain white man, had no idea that it was that same man who now stood beside him, apparently also black. There are some who question how easily Griffin passed for black given his otherwise rather obviously Caucasian features. There seems to be absolutely no doubt that he did as the book describes so we can perhaps be sure that it was the colour of his skin only that registered in terms of his identity – the shape of his nose or face was immaterial. I have also seen comments that query how on the basis of a few weeks experience Griffin is suddenly qualified to speak for all black people. I’m not sure he ever claims or suggests that and of course the book is no more than one man’s snapshot, however telling it may be. Sam McKenzie Jr. Is of the view that the book is something of a con and what Griffin discovered was known and talked about by black people for centuries beforehand,

‘Here’s my analysis— Griffin’s best seller is black-face. While Griffin’s book and his experience do not mock or dehumanize Blackness, I still see a silhouette of black-face .

It may be that this ignores the historical context and the fact that, if Griffin’s account is to be believed, his contribution was welcomed by the black community of the time and he did much work with some notable Civil Rights figures. McKenzie also points out that Griffin was not the first to disguise himself as he did. Ray Sprigle, a white journalist, published a series of articles entitled, ‘I Was a Negro in the South for 30 Days’. These were eventually gathered into book form and published as, ‘In the land of Jim Crow in 1949’. This criticism seems duplicitous – was it the wrong thing to do or had it already been done – it’s hard to see how he can be castigated on both fronts.

The reaction to the book, as recorded by Griffin, was generally favourable with far more positive than negative responses. However, the negative reaction was there, and eventually, he and his family decamped to Mexico for safety’s sake. Some years later he was badly beaten at the side of the road after his car broke down, taking 5 months to recover from his injuries. It was suggested but never proven as far as I know, that this might have been a revenge attack with Klan involvement. It would be a coincidence in the extreme if the lynch mob happened to pass by right at the time his car failed. There is, however, no report of a robbery and one might wonder why a group of men might beat an unknown white man with chains just for the hell of it.

Griffin died in 1980 at the relatively early age of 60. Whilst it has been suggested that this may have been caused by the medication he took to change colour there seems to be no truth in that. He left behind what I regard as an important and readable book, which may have dated in 60 years, but not so much as it might. Re-reading it I still came across ideas and viewpoints that caused me to think afresh and I concur with the advice he was given at the time – that he had a lot of bottle to do what he did.

It is a bit (a lot, actually) mainstream but here’s Mickey Guyton with her song inspired by the book. ‘Black Like Me’ received a nomination for Best Country Solo Performance at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, making Guyton the first black woman to receive a Grammy nomination in that category.