A dark family drama played out in a rough world of its own.

It feels like a good idea to widen the scope of this feature with a novel or two, perhaps a volume that has been unjustly neglected. Hopefully, the choice I have made embodies some of those themes that exemplify much that is American and that the writers we tend to admire pen songs about. Man against nature, rugged individualism, small-town life, family, relationships, love and death – that sort of thing!

It feels like a good idea to widen the scope of this feature with a novel or two, perhaps a volume that has been unjustly neglected. Hopefully, the choice I have made embodies some of those themes that exemplify much that is American and that the writers we tend to admire pen songs about. Man against nature, rugged individualism, small-town life, family, relationships, love and death – that sort of thing!

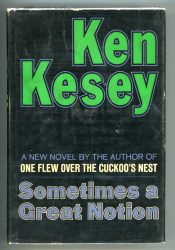

It’s my guess that there won’t be many readers of this website that are not familiar with Ken Kesey and his most famous book, ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest’. There may well be even fewer who are not familiar with the film version, featuring one of Jack Nicholson’s greatest performances – wherein he acts rather than mugs his way through proceedings. Fewer though might be familiar with Kesey’s second novel, ‘Sometimes a Great Notion’, written in 1964 – which a good number would claim to be the superior literary work.

It’s a doorstopper of a book running to over 600 pages and it is not an easy read, but it is very rewarding. It’s set in the fictional logging community of Wakonda in the Pacific Northwest and Kesey – who looks like he may well have chopped down a few trees – seems to know his way around. He did in fact spend research time with loggers. Famous as he was it was almost as much as a personality than as an author (a particularly American affliction) and he might be best known for his Merry Prankster escapades. Nonetheless, there are claims that this might be the Great American Novel, a grail after which many seek, have sought, and endlessly written about. The defining characteristics might be that the GAN is not yet written, is endlessly debated and it will ruin everything if it ever does come to print. Still, people keep trying and, ‘Sometimes’, is as good a candidate as any.

In, ‘1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die’, Margaret Anne Doody declares the book is, ‘A raw exploration of the survival of the American dream and a near-mythic fable of man pitted against nature, community, and big business’. Further, ‘The novel is an important and unjustly neglected classic of American literature’. Hign praise.

The book centres around the Stamper family – a bunch of hard-nosed independent loggers whose motto is, ‘Never Give an Inch’. Father Henry has two sons by two different women – Hank is the brawny bull moose, ex-football star who no man dares cross, a chip off the block that shaped Henry, though not quite so unpleasant. Hank is the epitome of the western man, a cowboy with an axe rather than a gun. The defining image is of him training as a swimmer by stroking upriver against the current and going precisely nowhere – swimming as he does in a river that no one else cares to even enter.

Half brother Leeland (Lee) is the spectacle-wearing cerebral child gone east to get an education. A dope-smoking John Coltrane fan whose head is a mess and recently botched a suicide attempt. Half brothers as they are they could not be more unalike. Two additional central characters are Viv, Hank’s wife and Joe Ben or Joby, Hanks cousin who represents the moral good-hearted epicentre of the book – everyone likes Joby who is a believer, a religious man. Whilst much of the plot turns on Viv this is not a book about women and she is an underdeveloped character in both the book and the film version where Lee Remick plays her as a presence rather than a wholly developed person.

The book opens rather confusingly with some scene-setting history whilst the reader becomes accustomed to Kesey’s writing style. However, the main course is the psychodrama that unfolds throughout between Lee and Hank. Ostensibly the family are short-handed and send for Lee as an extra body at a time when there is a local strike and the involvement of the union against Wakonda Pacific (WP), the logging firm. The Stampers don’t down tools, they carry on working and make the town increasingly resentful. Kesey balances the strikers feeling that everyone (ie the Stampers) should stick together, that they owe something to the town, with the pertinent question as to what the town has ever done for the family. This is particularly so in light of how little help and encouragement Henry received when he started his business, only to prosper against all odds.

Lee’s reason for returning is the desire for revenge against Hank – who, by the middle of the book we are finally given to understand had a sexual relationship with Lee’s mother, Myra Stamper, Henry’s second wife. She has recently committed suicide by jumping from a high rise and Lee seeks satisfaction, hoping to do so by way of seducing Viv – who it has to be said rather conveniently obliges – which might be the one questionable aspect of the plot.

In the film of the book, released in 1971, directed by and starring Paul Newman Hank eventually challenges Lee as to, ‘who was banging who?’ , given that he was 14 at the time and Lee’s mother was 30. There is no mention of that in the novel – with the film veering more toward being a Western with trees and chainsaws, eschewing the intense two-handed psychological drama of the original novel.

A precis of any plot can make it sound ridiculous but it all plays out convincingly enough – and given those 600 pages it has the space to do so. Kesey makes great use of multiple voices and viewpoints, including Lee’s letters to his college friend Peters, in order to expedite the narrative. Hank is presented as a basically honest but stubborn man who carries the weight of family traditions and expectations with increasing difficulty. There are times when he admits that he would just like to be liked. Driving it all is the even more hardbitten and sometimes odious Henry Stamper.

The prose is dense but ultimately feels right and appropriate as the labyrinthine tale unfolds. There have been comparisons with the style of Faulkner, Woolf and even Joyce and here’s a great quote from the ‘Good Reads’ forum that acknowledges the underlying machismo on offer whilst also capturing the technical quality of the writing;

‘If V. Woolf had a) grown up within sight of the Coastal Range, and b) enormous, swinging testes, then this book would be sold in a 3-pack with “Mrs Dalloway” and “The Waves” today’.

All the action takes place in the heart of timber country and the Stamper’s home is built next to and constantly reclaimed from the threat of the river – partly disappearing into it at the end of the book – it’s clearly a metaphor for the Stampers themselves. The sense of raw nature permeates proceedings from beginning to end and Kesey shows great talent in his descriptions. When I first saw the house in the film version I was quite affronted given that it hardly matched the strong mental picture I had derived from the written word.

And there is the rain, the endless rain, rain that brings out the union president’s athletes foot and saturates everything in sight. Kesey populates the book with a host of minor characters who form a chorus and backdrop to the main events, providing a framework by which we can watch the passing of time. If this is a book about a family it is also very much about a community and the book ends with Indian Jenny, a constant though marginal character, still dreaming of the union she never had with Henry Stamper. The thoughts of such as union steward Floyd Evenwrite, the musings of bartender Teddy and local businessman and failed suicide Willard Eggleston contribute to the story of the whole town as much as that of the Stampers. We even get some thoughts from town bully Biggy Newton.

The race is on for the Stampers to meet their contract with WP and not unexpectedly things go wrong and in a logging accident Joby is killed and Henry loses an arm. The death scene is handled very affectingly in the book and the film version, which has been described, rightfully in my view, as one of the great cinematic scenes of its time. Joby’s funeral is a skilfully rendered set-piece and brings out the hypocrisy of the town – yet also reminds us of what a good, popular soul Joby was in life.

Henry ends up in the hospital and it becomes clear that his decline is permanent, his part is played and eventually, he dies. During this time Lee makes his move on Viv, (yes it’s all action) but fails to carry it through at the last minute – it is Viv that initiates physical contact while Hank watches through the same hole in the wall that Lee used to spy on him with his mother. Viv’s actions are not wholly convincing though her sympathy has been clearly aroused by Lee as he plays the wounded butterfly. She ends up declaring that she loves them both but stays with neither and leaves. It is clear whereas Viv was to be the unwitting vehicle of Lee’s revenge that he does fall in love with her.

You might expect that Hank would then kill Lee – who was well aware that he was watching and lost no opportunity to twist the knife – yet somehow the explosion is delayed. They do eventually fight with Viv watching on. Significantly Lee fights back and this is a departure from previous episodes when Hank rescues him from a ‘Devils Stovepipe’ and later a group of youths who threaten to drown him. Whilst he remains passive in both those episodes on this occasion Lee deliberately goads Hank with reported expressions of sympathy and charity from the townsfolk as they seek to rub in what they consider to be their victory, with Hank having declared that he cannot meet the WP contract. This misplaced gloating is more than Hank can bear and knowing that he does actually have enough timber to meet the contract he sets of to do just that with the help of one of his kin – and Lee!

If things were complicated before they are even more so now. Lee has become aware that there is a sizeable insurance policy in his name that Henry has taken out and in searching for the documents he finds correspondence between his mother and Hank that contains poetry he wrote for his mother. This enrages him and the suggestion is that she chose Hank over him – she betrayed him.

Whilst the implication is that after all Lee and Viv could get together the Stamper blood remains true to form – he can’t stand the thought that Hank should win after all and joins him in the final log run. In both the film and the book Henry’s severed arm, attached to the mast of the tug boat, gives the finger to the entire community as they float downriver.

It seems at the end then that Stamper bloody-mindedness rules the day – Viv is gone, Joby and Henry are dead. The brothers join forces to deliver the wood and are certain to alienate the town – the town which when it thought Hank was beaten was left puzzling as to whether this was satisfactory or not. Arch rival Biggy Newton unexpectedly stands up for Hanks reputation declaring that he never backed away from anyone. Hank – the hero they loved to hate until disappointingly he seemed beaten and let them down?

This book is a lengthy read that requires concentration, but given its length, there are no wasted words. There are passages that are hard to grasp, make limited sense or whose meaning is obscure, but it might help to just read on and grasp the whole and not the parts. If you spent the whole of, ‘War and Peace’, worrying about each character and who they are you would never reach the end. It’s just a war story after all – isn’t it?

A final mention of the film – which I have alluded to in parts. It is 50 years old and shows it at times. Newman became the director by default as others dropped out. He handles the outdoor action scenes well and is careful to avoid melodrama. Henry Fonda makes a pretty good Henry Stamper and Newman has the presence (including that unsettling grin) if not the obvious physicality to make a good Hank. Lee Remick as Viv – well I found her a bit two-dimensional. Michael Sarrazin as Lee does well but he was not the image I had in mind as I read the book. Let’s be fair that is not long hair and to these eyes, he just doesn’t look different enough to be the outsider. All that considered it is an underrated seldom seen film that deserves a look. It avoids some of the deeper, darker aspects of the book and proves that film cannot match a novel when it comes to describing a characters most secret inner world, especially the depths of a psyche as twisted and tormented as Lee’s.

The title of this book comes from the song ‘Goodnight Irene’.

“Sometimes I live in the country / Sometimes I live in the town / Sometimes I get a great notion / To jump into the river an’ drown”