Fact, fiction – or an entertaining mix of the two?

In my personal reading and that related to the Paperback Rider articles one book has cropped up a number of times as something of a touchstone for others – ‘Travels with Charley’ by John Steinbeck. It was published in 1962 about a trip that took place in 1960 when Steinbeck skirted the borders of the nation in a 10,000 mile trip in a truck cum camper called, ‘Rocinante’, – after Don Quixote’s horse. He travelled from Long Island New York to the North West Coast, down to his hometown of Salinas in California across Texas, through the deep south and back to the Big Apple. Interestingly he says he was never recognised – but as we discover there may be something of an explanation for that.

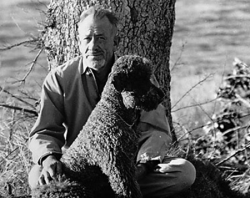

His travelling companion was a Standard Poodle called Charley who despite an appalling choice of hairstyle proved to be a loyal and wise accomplice. After many years of travels in Europe and living in a variety of places including New York Steinbeck decided he needed to reconnect with the people of America and to see what the lay of the land might have become. This was at the time of the Nixon Kennedy election and in retrospect a significant watershed in American history.

Steinbeck was to receive a Nobel prize only months after the publishing of, ‘Charley‘, and it would be fair to say that his popular profile probably outmatched that of his critical stature. He has been accused of overly sentimentalised depictions of social issues with no real offers of viable answers – offering only problems but no solutions. I’m not convinced that offering solutions are a novelists job.

My own view is that he has written at the two extremes of his art. ‘Grapes of Wrath is, for a number of reasons, one of the great books of the 20th century. One of the worst by any major author is, ‘East of Eden’, with a clunky plot that becomes almost risible as it moves to a close.

‘Travels with Charley’, was and is a hugely popular book, a number one seller for a week at the point of release (replaced by Rachel Carson’s, ‘Silent Spring’, as it happens). However one question dogs (no pun intended) the whole issue – is it a true account?

Travelling around America in the luxury of a custom made camper seems small beer compared to, say, cycling it in a smidgen under 7 days 16 hours. Indeed such is the current way of life for many – see, ‘Nomadland’, – that extended travel seems no great thing. I’m sure that someone has done it while walking on their hands with a fridge on their back. How many times did Forrest Gump cross the nation? Pete Kostelnick ran it one way in a little over 42 days. There are no prizes for hardship but some careful research by Bill Steigerwald tells us,

‘Steinbeck was almost never alone on his trip. Out of 75 days away from New York, he travelled with, stayed with, and slept with his beloved wife, Elaine, on 45 days. On 17 other days, he stayed at motels and busy truck stops and trailer courts, or parked his camper on the property of friends. Steinbeck didn’t rough it. With Elaine he stayed at some of the country’s top hotels, motels, and resorts, not to mention two weeks at the Steinbeck family cottage in Pacific Grove, California, and a week at a Texas cattle ranch for millionaires. By himself, as he admits in Charley, he often stayed in luxurious motels’.

The key question remains as to how much was travelogue and how much was invention – it seems that most are now willing to accept that there was a great deal of the latter – or at very best, extensive non-sequential cutting and pasting. The author does have contact with people as he travels but much of the book is taken up with his own ruminations. He admits towards the end that he begins to avoid contact and can’t get home fast enough. Whilst the American penchant for wanderlust is much-trumpeted it seems that some travellers, William Least Heat-Moon is another, are very glad to get home again. Compare that to the wonderful Bernard Moitessier who, toward the front of the first round the world yacht race, decided to crack on and went a further two-thirds of the way around the globe before stopping and thus losing any chance of fame and fortune by actually crossing the finishing line first. That’s a hardcore traveller. Lewis and Clarke are much referenced by modern travellers and though they were clearly different times their journey was measured in years – not days.

Steinbeck biographer Jay Parini takes a more pragmatic view in a new York Times interview,

‘I have always assumed that to some degree it’s a work of fiction. Steinbeck was a fiction writer, and here he’s shaping events, massaging them. He probably wasn’t using a tape recorder. But I still feel there’s an authenticity there. Does this shake my faith in the book? Quite the opposite. I would say hooray for Steinbeck. If you want to get at the spirit of something, sometimes it’s important to use the techniques of a fiction writer. Why has this book stayed in the American imagination, unlike, for example, Michael Harrington’s, ‘The Other America’ which came out at the same time’’?

That’s never a fair comparison given that one was a ground-breaking sociological text written by an academic and the other a relatively light biographical travel book filled with amateur philosophising. It’s nonsense to compare chalk with cheese.

Bill Barich, who later retraced Steinbeck’s footsteps, wrote,

‘I’m fairly certain that Steinbeck made up most of the book. The dialogue is so wooden (to be fair that is a complaint about much of his fiction). Steinbeck was extremely depressed, in really bad health, and was discouraged by everyone from making the trip…..I still take seriously a lot of what he said about the country. His perceptions were right on the money about the death of localism, the growing homogeneity of America, the trashing of the environment. He was prescient about all that’.

Perhaps most simply Steinbeck’s son, in a new York Times article of 2011, believed that his father invented much of the dialogue in the book, saying: “He just sat in his camper and wrote all that [expletive].” Does he mean shit?

But – whether it was fact or fiction or a mixture of the two – how good a book was it?

The best descriptive passage might well be the storm that occurs in Sag Harbour before he even sets off. The most interesting might be the description of Texas – clearly, a place he has a great affection for and which is the home state of his wife. He reminds us that Texas is the only state that joined the Union by treaty and that it can still secede if it chooses. Helpfully, such as Ted Cruz, have kept that information in the public eye. Whether they are aware that Steinbeck apparently founded a society to assist that process is not clear and of course it may be defunct by now. I think the operative phrase is, ‘calling your bluff’.

The most chilling episode occurs when Steinbeck watches the ‘Cheerleaders’ berating a young black girl and a white man taking his child to the same integrated school. He chooses not to report word for word what is said and somehow the account loses nothing by that omission. Soon after he meets a reasonable white man, a clearly scared black man, a virulently racist white man and finally a rather more angry and impatient black student. Perhaps it’s just serendipity that these characters appear so neatly in order to illustrate his account.

There are constant reminders about his New York licence plates and how they might be perceived – so Steinbeck’s claim that the American Identity is an ‘exact and provable thing’, doesn’t quite ring true. He speaks, for instance, of the taciturnity of New Englanders and the generous nature of Mid-westerners and Texans. In order to present believable bona fides, he takes guns with him – so he’s a hunter, not a communist agitator or troublemaker if he is challenged. He does meet kindness on the way – for instance the story of the burst tyre and the, ‘Guardian of the Lake’, who lets him stay on private land. That said mostly he is insulated from the common man and in any of the many travel books I have read it is often clear that the journey could not take place without multiple assistance and kindness from what we might call ‘ordinary’ people who are strangers. Steinbeck is a ‘credit card’ traveller and has a relish for luxury stops.

Steinbeck’s musings do not necessarily need travel to inspire them and tend to reflect the theory of the Golden Age – existing 30 years prior to any given moment in time – although in his case that would be the 1930’s, a curious choice. His comments about truckers, Free-ways and the growth of mobile homes would seem most likely to be a product of his journey, but for a man who wrote a great deal about the poor and dispossessed he does not encounter them much on this trip. He does comment on the, ‘Fantastic hugeness and energy of production’, in various towns, ‘Great hives of production – Youngstown, Cleveland, Akron, Toledo, Pontiac, Flint … South Bend and Gary’.

Where and what are they now?

It’s no surprise given the rest of his literary output that Steinbeck has a very orthodox view of masculinity. He talks of life to be lived with a sense of ‘quality‘ and not a search for ‘quantity‘ and his thoughts about conviction and idealism seem to involve the possibility of ‘man-fights’ to back it up. If a polarised view might be praised as aggressive single-mindedness, then contemporary America perhaps illustrates it might be better served by understanding and tolerance. Steinbeck’s machismo orientated world, which is what he seems to think every woman wants in a man, seems very old hat and outdated. None of this is likely to be any surprise in a book written 60 years ago in a world about to be cut off at the knees by the counter culture. It’s a question as to whether it makes any less of a good read.

Having first read this book as a teenager I was surprised to discover just how many questions were raised regarding its accuracy during my re-reading. Whilst I had also been forced to revise my opinion of Steinbeck having read, ‘East of Eden’, it is still the case that he is rarely less than readable – believable is another issue entirely. Modern travel books have changed a great deal since, tending to get much closer to both the people and the land, dispensing with too much polemical philosophising and probably seen as better for it.

Really enjoy your literary review pieces and pleasantly surprised to see you previously championing Rory Stewart’s great writing on AUK of all places.

There is plenty to be said that counters your take on East of Eden.

Thanks for the kind comments David and glad you enjoy the series – as a writer you always wonder how things do down with the readers.

Though its not strictly AUK territory I have great respect for Stewart as a writer – though I was a bit disappointed with The Marches’ which felt a bit unfocussed at times.

I think he is a decent man and in the leadership election he stood out like a sore thumb compared to the rest – and very much to his credit it was too. Because he doesn’t and never wiil look the part he has no real chance at leadership and really that’s ultimatelly a good thing in my view. As you will no doubt be aware he is also a very brave man – there’s no way I’d take the walk he did

I understand he has an American academic post at present.

As for East of Eden I’m sorry but we part company on that one – the plot became so risible toward the end that I struggled to finish it – and I’m one of those who hates not to finish a book. I’d be interested in your alternative view though

Re East of eden,briefly and superficially, i thought it a monumental book. Powerful interweaving of highly nuanced compelling characters who evolve through time,through interplay with others and through circumstance. The “monster” through whom much of the narrative unfolds is imo an example of the absence of ability to empathise that so many murder trials painfully bring out via evidence.

Amazingly intricate crafted plot which in my view never really defies credibility. Its clear from the outset that the tale is to aim for biblical status and to do so in the grand sweep of USA society evolving over the period in question. And hey,melvyn bragg is with me on this.

Re the book actually reviewed in your piece, I admit not having read it yet tho am taking the scenic route having read and loved Geert Maks 50th anniversary revisiting of the trip and book.

Being a proud West Cumbrian and having friends in Wigton I am almost persuaded by the Bragg reference but to be honest I still have to say I found it one of the most annoying books I’ve read in a long time.

I know it’s merely an artistic device but it sort of reminded me of those bizarre scenes in Westerns where protagonists – being able to travel, what, 20 / 25 miles a day – miraculously run into each other – often time and again. If it weren’t such a hefty book then I might give it another go but on reflection, life’s too short

Is the Gert Mak book worth a read?

Given we have plenty of common literary ground based on your reviews so far I think you’d like Mak’s books. And you seem well placed to arrange a bookish face to face with Lord B!

Well David my next effort is due for posting towards the end of next month – I’lll be interested to see it it maintains our common literary ground – its a bit of a departure!!