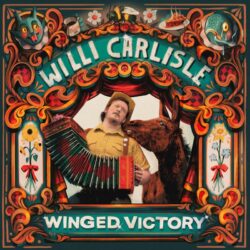

Willi Carlisle comes up with an album which is both defiant and hopeful.

“When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” So wrote Hunter S. Thompson back in the 70s amidst the turmoil of the Nixon years. These days, we’re in the midst of much worse turmoil, and it’s gratifying to find that Willi Carlisle is well able to capture this in his own inimitable fashion.

“When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” So wrote Hunter S. Thompson back in the 70s amidst the turmoil of the Nixon years. These days, we’re in the midst of much worse turmoil, and it’s gratifying to find that Willi Carlisle is well able to capture this in his own inimitable fashion.

“Winged Victory” finds Carlisle still rooted in the roots of American music, be it folk, talking blues or string band, with a fine blend of original songs and covers. There’s a thread woven throughout the album, although it’s quite discreet for much of the time; you couldn’t really call it a collection of protest songs, but there are elements of pride and defiance on show while Carlisle makes sure that he celebrates the possibility of hope. Like the Dude, Carlisle abides.

To this end, there are several songs here which, quite simply are quite gorgeous. ‘Wildflowers Growing’ cautions us to be mindful of the small things in life, which are more important than the ephemera which is beamed at us via TV screens, while’ The Cottonwood Tree’ is an idyll about a childhood’s imagined safe place. It’s wonderfully realised with huffs and puffs of squeezebox girding the song, and it’s reprised later on in a brief instrumental which is vaudevillian in its delivery. Carlisle also throws in a very creditable cover of Richard Thompson’s ‘Beeswing’ which sits well within the album’s confines.

Fine as these songs, are the meat of the album is to be found in those songs which can be considered “pertinent” to these days and Carlisle reaches back to the past on the opening strident bustle of ‘We Have Fed You All For 100 Year’s, his recovery of an old IWW (Industrial Workers of the World AKA The Wobblies) song which basically shows that, decades later, workers are still being exploited. Even more strident is the howl which is the title song, where Carlisle, solo with banjo, basically rants against the idea of progress as sold to the working class. That it is imagined by an elderly worker who befriends a mule and who ends up in a dementia ward, still protesting, is quite amazing. ‘Work Is Work’ is more energetic with the instruments flailing away, with Carlisle eschewing the imbalance between workers and those who work them. Cleaving to his avowed queer identity Carlisle gives us a rollicking old time vaudevillian version a song by Patrick Haggerty, leader of early gay pioneers Lavender Country in the shape of ‘Cock Sucking Tears’ while ‘Big Butt Billy’ is a talking blues which finds an archetypical trucker pulling into a diner and becoming enthralled by his waiter, an “elphin specimen of the non binary kind.” It’s lascivious and witty and performed quite wonderfully as Carlisle becomes increasingly engrossed by Billy’s perfectly defined butt and emotes about it in the manner of a radio evangelist. This is both great fun and a definite finger held aloft, a bird to the more straight-laced members of the community.

Rounding off the album is the a cappella ‘Sound And Fury’, which digs into Gospel sounds while the closing song, ‘Old Bill Pickett’, is given a great bluegrass delivery as Carlisle pays tribute to a legendary black rodeo rider. Overall, a fine album which can be summed up in Carlisle’s own words. “These songs feel poised on the edge of the apocalypse, or at least at the beginning of a great transformation in America. During this borrowed time, the weirdos, cowboys, and dreamers in these songs dare to love, and often pay for it with blood.”