When I knew I was going to be covering the letter W in the latest round of the A-Z of Americana I considered a number of options – Lucinda Williams, Willie Nelson, Wilco… but I ended up going with one of Texas’ favourite sons, Waylon Arnold Jennings.

When I knew I was going to be covering the letter W in the latest round of the A-Z of Americana I considered a number of options – Lucinda Williams, Willie Nelson, Wilco… but I ended up going with one of Texas’ favourite sons, Waylon Arnold Jennings.

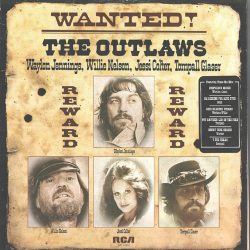

Waylon Jennings was the main driver of the Outlaw Country movement of the late 70s. Aided and abetted by his long time friend Willie Nelson, they took back control of the recording process from Nashville and Chet Atkins bland, smooth Countrypolitan sound but it was Waylon who was instrumental in getting out the compilation album ‘Wanted: The Outlaws’, featuring himself, Willie Nelson, Jessi Colter and Tompall Glaser. It gave focus to a new sound in country music and provided the first platinum album for a country recording. Without Waylon Jennings and the Outlaw sound, there’s a strong argument to say there’d be no Steve Earle, no Joe Ely, no James McMurtry and a whole host of other, left field Alt-Country musicians. It may not be pushing belief too far to say that, without the Outlaw Country movement, Americana, as we’ve come to know it, wouldn’t exist today. Outlaw was the first music that looked to mix country with other music styles, mainly Rockabilly and Honky Tonk, to create a harder-edged roots sound.

Born on a farm near Littlefield, Texas, Jennings started playing guitar when he was just eight years old, taught by his mother to play the Hank Williams song ‘Thirty Pieces of Silver’. It seems his future was settled from that point on. Waylon started establishing his outlaw credentials quite early in life – he was constantly in trouble in school for his problems with discipline and, at sixteen, the High School Superintendent “suggested” he might like to drop out and take his talents elsewhere. He quit school and went to work for his father in the family store but his main focus was always on music. At twelve years old he’d already secured his own 30-minute slot on local radio station KVOW and formed his first band, The Texas Longhorns. In addition to his slots at KVOW he also performed, on occasions, at country radio station KDAV, based in Lubbock and it was following a performance at KDAV that he met Buddy Holly at a Lubbock diner. They became friends and Jennings started hanging out at Holly’s Sunday Party programme at KDAV. It was inevitable that Jennings would relocate to Lubbock and he moved there in 1956 and started DJing on local station KVOW, where he ran a daily show from the late afternoon through the evening, playing a mix of country and other popular music. Being Jennings he started playing a lot more of the “other” music, including the likes of Chuck Berry and Little Richard – not a popular move with the country loving station owner. He was fired for playing back to back Little Richard records. Even in his teens Waylon Jennings was building a reputation for going against the country music establishment.

Jennings continued to work as a DJ around the Lubbock area, moving from one station to another as he built up his audience and became a sought after DJ for public appearances – not least because he would often perform as a musician at these appearances. This brought him to the attention of Buddy Holly’s father and, on his father’s recommendation, Jennings ended up being the first artist that Buddy would work with as a producer. It could’ve been the start of a great partnership. Holly hired Jennings on to play bass in the Crickets and they embarked on the Winter Dance Party Tour of 1959. The rest, of course, is history. On the tour Jennings gave up his seat on the chartered flight, from Mason City, Iowa heading to Moorhead, Minnesota to the 28 year old Big Bopper (J.P. Richardson). The plane crashed soon after take-off, killing all on board and ending the very promising careers of Richardson, Holly and Ritchie Valens, who was also on board.

Following the death of Buddy Holly, Jennings went back to DJing around the Lubbock area but soon moved to Coolidge in Arizona, so the family could be near to then wife Maxine’s ailing father. It was here he formed his band The Waylors and took up a residency at Scottsdale club JD’s, building up a strong local following for his increasingly harder-edged country music. In 1961 Jennings signed his first real recording contract with Trend Records before moving on to A&M in 1963. Bobby Bare, country music singer and writer of ‘500 Miles Away from Home’ heard Jennings in one of his regular slots at JD’s and recommended him to Chet Atkins, then head of RCA Victor. Jennings formally signed with RCA in 1965 and that year saw his first appearance in the Hot Country charts with ‘That’s the Chance I’ll Have to Take’. This was the start of Jennings’ first golden period at RCA; over the next seven years Jennings would enjoy a string of hits, both singles and albums, along with a Grammy Award for Best Country Performance by a Duo or Group in 1969, for his work with The Kimberly’s on their recording of ‘MacArthur Park’. But Jennings was becoming increasingly disenchanted with life at RCA Victor and the control exercised by label boss Chet Atkins. Though Jennings had never really given way to the “Countrypolitan” sound that Atkins promoted he was finding it harder and harder to make the records he wanted to make. Jennings wasn’t allowed to play on his own records and nor were his backing group – Atkins and his producers insisted on the use of local session musicians who would play exactly the way they wanted them to. Jennings wasn’t even allowed to select his own material, that was also the producer’s decision. They would add orchestral arrangements to his records and even tell him what he should be wearing when appearing in public – it all started to get way too much for a man who’d spent much of his life kicking against authority.

In 1972 Jennings was laid up recovering from hepatitis and increasingly depressed at his situation. He was broke and paying alimony to three ex-wives, the IRS was hassling him and he wasn’t gigging because of his illness. He was visited by his drummer, Richie Albright, who suggested he hire Neil Reshen as his manager. It was an inspired suggestion. Reshen was a business manager at the rock music magazine Creem and already handled the careers of jazz legend Miles Davis and iconic bandleader Frank Zappa. He was used to working with strongminded artists and had a hard negotiating style when it came to tackling the record companies. He renegotiated Jennings’ deal with RCA and, as well as securing a better advance and more royalties, succeeded in getting Jennings the artistic freedom he craved.

This new freedom was the shot in the arm Jennings needed. His first two albums under this new RCA deal, ‘Lonesome, On’ry and Mean’ and ‘Honky Tonk Heroes’, both released in 1973 were the start of his most critically and commercially successful years that would run throughout the 70s. He obtained his first number 1 on the Billboard Country Singles charts with the self-penned title track from his 1974 ‘This Time’ album.

Throughout the Seventies his albums enjoyed huge success, with six albums in a row achieving gold record status and, of course, the seminal ‘Wanted: The Outlaws’ becoming the first country album to achieve Platinum status. He achieved major singles success with tracks like ‘Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way’, a thinly veiled attack on the country establishment, and the duet with Willie Nelson ‘Mamma, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys’. He even took time to criticise the Outlaw movement he helped to start with the top ten country hit ‘Don’t You Think This Outlaw Bit’s Done Got Out Of Hand’. Never one to rest on his laurels, Jennings and his band continued to push at the boundaries of country music even when they were enjoying major success.

Throughout the Seventies his albums enjoyed huge success, with six albums in a row achieving gold record status and, of course, the seminal ‘Wanted: The Outlaws’ becoming the first country album to achieve Platinum status. He achieved major singles success with tracks like ‘Are You Sure Hank Done It This Way’, a thinly veiled attack on the country establishment, and the duet with Willie Nelson ‘Mamma, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Cowboys’. He even took time to criticise the Outlaw movement he helped to start with the top ten country hit ‘Don’t You Think This Outlaw Bit’s Done Got Out Of Hand’. Never one to rest on his laurels, Jennings and his band continued to push at the boundaries of country music even when they were enjoying major success.

In the 1980s record sales started to decrease as country music suffered a drop in popularity, though Jennings continued to be a major live attraction, especially when he teamed up with Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson and long time close friend Willie Nelson in supergroup, The Highwaymen.

He moved to MCA Records and then to Epic, where he recorded his last top ten album, 1990s ‘The Eagle’ but Jennings always remained active as a touring and recording musician even when the good times weren’t quite so good. He recorded his last album ‘Never Say Die: Live’ at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium in the year 2000.

Waylon Jennings died in 2002. The years of heavy smoking (six packs a day at one point), drug abuse (he recovered from both amphetamine and cocaine addiction), a heart bypass and the amputation of his left foot due to circulation problems caused by his diabetes – all finally caught up with him. He was 64. He was married four times and was father to six children; Jessi Colter, who he married in 1969, was his fourth wife and was with him to the end.

It’s impossible to overestimate Waylon Jennings importance to country and Americana music. In 2017 Steve Earle released ‘So You Wanna Be An Outlaw’, his tribute to Waylon Jennings and the Outlaw movement he helped to create. “I was out to unapologetically ‘channel’ Waylon as best as I could.” Earle said at the time, “This record was all about me playing on the back pick-up of a ’66 Fender Telecaster on an entire record for the first time in my life”. Earle has gone on record as saying that without Jennings and his ground-breaking separation from the Nashville country machine, artists like him would not be able to make the music they do. Waylon Jennings wasn’t the only artist kicking against the establishment at the time and recognition has to go to other artists like Willie Nelson, Tompall Glaser, Billy Joe Shaver, Jessi Colter, Tanya Tucker, Kris Kristofferson and many others – but it was Jennings that took back control from the Nashville establishment and created an environment within country music where these artists could flourish. From the very start he set out to blend rock and roll and rockabilly into his music to ensure it had that harder edge that characterised his sound. Waylon Jennings was always an original and he was always an Outlaw!

Key Recordings: Where do you start when you’re dealing with such an iconic figure whose recordings covered some five decades? Obviously the ‘Wanted: The Outlaws’ album is a hugely important record and should be in everyone’s collection but the two albums previously mentioned, when he first took back artistic control of production, ‘Lonesome On’ry and Mean’ and ‘Honky Tonk Heroes’ are also hugely important as is 1972’s ‘Ladies Love Outlaws’, the last album recorded under his original RCA deal and the one that signalled his future musical intentions. 1978’s ‘Waylon & Willie’ album is a particularly fine collaboration as, of course, is ‘Highwayman’, 1985’s debut album from the country supergroup The Highwaymen. But you could also go back to some of his earlier performances and the albums released then to see the roots of what Waylon Jennings originally set out to do. Below is a 1970 recording of his version of ‘Brown Eyed Handsome Man’, the Chuck Berry song he played to death back in his DJ days. Waylon Jennings was a rocker.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJI1N61grmc