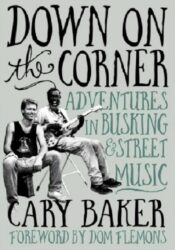

Cary Baker’s opus is subtitled “Adventures in Busking & Street Music“, and it takes a look at the busking scene by focusing in on some particular artists and lively street music locations and eras when busking was more popular or less likely to run up against issues with regulations and the police. Some of the chapters are very focused on a couple of particularly vibrant “scenes” mostly coupled to blues music, but this is all backed up with the recollections of their busking lives by some notable musicians who went on from such humble street gigs to playing some of the major music rooms of the world. It’s too much to expect that it could be a definitive overview of all busking everywhere, and the focus is particularly on North American cities, although the sections where well-known musicians give their personal take on their own busking histories, and busking in general, does include a section of Europe, which gives room for the likes of Elvis Costello and Billy Bragg. Moving from the medieval troubadours, the sections on modern busking’s early history leans hard into the blues, and is populated with any number of blind blues men and women since busking was one for of work available, and highlights the potential for musicians to be “discovered” on the streets – citing several buskers who got to make one or two albums, sometimes more, including a lucky few during the early proto-rock and roll era of street corner groups performing “doo-wop” style.

Cary Baker’s opus is subtitled “Adventures in Busking & Street Music“, and it takes a look at the busking scene by focusing in on some particular artists and lively street music locations and eras when busking was more popular or less likely to run up against issues with regulations and the police. Some of the chapters are very focused on a couple of particularly vibrant “scenes” mostly coupled to blues music, but this is all backed up with the recollections of their busking lives by some notable musicians who went on from such humble street gigs to playing some of the major music rooms of the world. It’s too much to expect that it could be a definitive overview of all busking everywhere, and the focus is particularly on North American cities, although the sections where well-known musicians give their personal take on their own busking histories, and busking in general, does include a section of Europe, which gives room for the likes of Elvis Costello and Billy Bragg. Moving from the medieval troubadours, the sections on modern busking’s early history leans hard into the blues, and is populated with any number of blind blues men and women since busking was one for of work available, and highlights the potential for musicians to be “discovered” on the streets – citing several buskers who got to make one or two albums, sometimes more, including a lucky few during the early proto-rock and roll era of street corner groups performing “doo-wop” style.

The book has a middle section of photographs of various of the musicians discussed or interviewed – this includes a wonderful shot of a pre-rocking Lucinda Williams in dress and bonnet – as well as album covers and photographs of musical ephemera.

Cary Baker has a storied career as a music writer, record re-issuer and publicist, amongst other things, and, significantly, in 2006, he was named the Blues Publicist of the Year at the Blues Foundation’s Keeping the Blues Alive Awards. Which explains the blues bent of the opening chapters “Maxwell Street Part 1” and “Maxwell Street Part 2” – the first was originally written in 1981 and is a document of a lively blues busking scene (it was featured in the Blues Brothers film) attached to a vibrant market area on the edge of the Chicago campus of the University of Illinois, whilst the second reflects on later musicians who plied a trade up until the destruction of said scene by the expansion of the campus and the less than successful relocation of the market. It’s like the tale of Covent Garden in reverse – moving the vegetable market out of central London allowed for “trendy” new shopping and a regulated street entertainment centre to be created; for Maxwell Street, the vibrancy and organically grown symbiosis of market and entertainment couldn’t be rekindled in a far more sterile new location.

Baker goes on, in a series of short chapters, to give overviews of the careers of notable figures in the busking scenes, which are gathered under headings of “The East Coast“, “South and Midwest“, and “California“, with a short section on “Europe“. There are portraits of those long gone – a potted history of the life and times of Moondog, for example, with his significant influence on the development of modern jazz and modern classical form music – and short interviews with those either more recently, or still with us. Ramblin’ Jack Elliot shared anecdotes both of playing for free in Washington Square, which he states “wasn’t busking – that was just singing for the fun of it“, and the ups and downs of busking for six years in Europe – including inspiring a young Mick Jagger – before stating that he had no fondness for street-singing and busking. Madeleine Peyroux had happier memories of busking around Europe, and advice for which countries to avoid because “people are really nice, but there’s no cash.” There’s a grittier bag of advice from Mary Lou Lord – some not so bad, learn some Fairport Convention and Richard Thompson songs – and others really quite practical like don’t let people piss in your collection pot. The ultimate good luck story surely belongs to Old Crow Medicine Show, who tell of getting a big break – being invited to play Merlefest by Doc Watson after his daughter discovered them busking on the street.

A music city like New Orleans gets more room in the book – with three chapters covering the origins of street playing and jazz with characters like Kid Ory, through the blues era of the fifties and right up to modern times where the city has recognised that street performers add a vibrant side of random musicality to a city which draws visitors in largely through its musical legacy. That’s something of a theme to the book, as different approaches from total bans to a far more relaxed attitude to the policing of busking are adopted by different municipalities. It ties back into the roots of the art form – with questions of where does busking start and begging end.

The section on European busking somewhat surprisingly doesn’t tell what to my mind is the greatest British busking story: to promote the film “Give My Regards To Broad Street” Paul McCartney supposedly busked at an entrance to Leicester Square tube station (actually filmed at Little Newport Street). Not many people recognised him, and he didn’t take a lot. The Guardian (or maybe it was The Independent) sent several of their staff out to see how they might get on; several outdid McCartney, including one journalist who played the harp and both topped the takings league and got booked to play a wedding. It also overlooks the historical pilgrimage to Paris of so many British jazz and blues buskers – although this is partly hinted at in the interview with Ramblin’ Jack Elliot elsewhere in the book. This is, fundamentally, a book about the United States – Europe is touched on a little, even then with a somewhat American slant, and the rest of the world doesn’t exist.

With its short chapter structure, “Down On The Corner” is a book much better dipped into than read cover to cover, particularly with the somewhat similar stories of busking lives – quite often, quite brief periods of their careers – that the “names” provide. There are a few places where a little more editorial attention could have cleared up typos, although one at least has a beautiful structure, where Billy Bragg talks about being politely turfed off other people’s pitches: “But I did get I did have a few encounters with people who [told me] was I was on I was on their pitch.” That “was I was on I was on” should be in a song somewhere. It’s an interesting read, Cary Baker rightly doesn’t disguise his main areas of interest in the Blues and closely related genres. It also captures how the modern world is changing this way of music-making – as it becomes ever more regulated and, in a cashless society, somewhat harder to make work for the player.