Catholicism and Pentecostalism, with some sacred steel and concrete details.

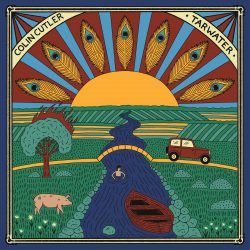

Americana is a broad church, and Colin Cutler’s love of folk and roots music means this Greensboro, North Carolina resident fits right into the genre. Where it gets interesting is that Colin Cutler, as well as being a folk, roots, and old-time musician, is also ex-military and he has a Masters in Creative Writing. His third album ‘Tarwater’ sets Flannery O’Connor’s short stories to music. Flannery O’Connor was a Georgia native who as well as being a middle-class woman was also a Catholic which gave her an outsider view of Southern society which no doubt helped her literary career in the Southern Gothic style. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson chatted to Colin Cutler at home in North Carolina over Zoom to discuss ‘Tarwater’ and the background that led up to it being recorded and released. Colin Cutler shares the influence that Flannery O’Connor has had on his own writing, as well as that of Bruce Springsteen, REM and Lucinda Williams. While clearly the American South has been a major influence, Colin Cutler also shares his fond memories of his time at York St John’s University and the enduring friendships he made there.

How are you, and where are you?

I’m on the upswing and life is good. I’m right here at home in Greensboro, North Carolina

As a Southerner, what does the South mean to you?

I say yes, I’m a Southerner, however, I was an Air Force brat and so I grew up all over. My dad’s from the South and my mom’s from the North, and I grew up in the Midwest and the South. I then moved down here and I decided to stay here, I have very much taken on being from the South, it is home and part of who I am. With that, I recognise there is a long history and a long debate on what it is to be Southern.

Family is a big part of being Southern, place is a big part of that because it wasn’t until the ‘40s and ‘50s that the South became as connected as the North East already was. Place ties to family land which is also very important. Religion is also very important, and we’ve been reading this book ‘The Carolina Table’ in the classes that I’m teaching and one of the common threads is that often the place that people come to a common table is at church. There are a couple of reasons for that, one is that the South is a pretty religious area and the church was a major community centre.

I found, in many ways, it parallels the North/South divide in England, but backwards, which is perhaps why I felt somewhat at home in Yorkshire. The American South tends to look backwards just as much as it looks forward. It has a long, twisty, and often painfully violent history to look back on, with plenty of folks to catch the fingers of blame, insiders and outsiders both. This perspective can manifest at its worst as a shallow reactionism. At its best, it’s progress with an eye toward nourishing and cultivating healthy roots. In many ways, those roots are carried forward prolifically in song and story, those are as much an export as our tobacco, peaches, peanuts, soybeans, cotton, and oysters.

You made a choice to go back to the South.

Yes, I did, and I lived over in England in York for about a year and a half, and I released my second complete album while I was there. That was the middle section of a four-year period when I lived overseas, and then I moved to Romania and when the pandemic hit I decided to come back to North Carolina. One of the reasons I felt the need to do that, and some of it was down to necessity, was that I realised I write better when I’m back here. Flannery O’Connor in her essays talks about writing being tied to seeing and seeing things deeply, and I think you can see things more deeply when you’ve been around them a lot. Sometimes you just pass over things you see a lot, but if you sit down and really think about them you can see the contours a lot better, plus you understand those contours a lot better if you’ve grown up with all the tensions that surround them as well.

I’ve lived in a lot of places with great musicians, but one of the reasons I moved back to Greensboro was its huge critical mass of fantastic storytellers and songwriters. I think that Piedmont is a place that is quiet enough to nourish the development of those stories, while also being connected enough to both avoid stagnation in one perspective and also to export them easily to the bigger world. It’s a place where the still, small voice can still be heard, but also amplified.

What drew you to Flannery O’Connor and what are your views on her work?

When I first encountered her I could tell she was good, but I didn’t know if I liked her. She has a bit of a savage pen and she can be dark as well, but I realised as I got into her that she had a very keen eye for picking apart things that I had grown up with too. She noticed the contradictions and drew them out in her character’s lives in a way they were eventually forced to look at them and make a decision. In her stories you don’t always see her characters making those decisions, she sometimes just brings them to that point of decision, and she is also hilarious as well in a darkly humorous way. She was sharply insightful about the many contradictions in Southern society, and in American society as a whole.

That also ties into one of the reasons I came back here to be based in the US, I released one song while I was in England called ‘American Man’, and it was about gun violence in America. The reception to it In the UK was well it is always like that in America and it is awful, but there wasn’t that emotional immediacy as there is when I’m playing it here. When I’m playing it here people in the audience may agree with what I’m saying or they may not, and the refrain is just “I’m an American Man, I’m an American Man”. I had an old friend from the army come to one of my shows, and he told me I’d got him with that song because he said he was thinking of Bruce Springsteen’s ‘Born In The USA’ with “I’m an American Man”, and then he started listening and he said he was like, oh. That’s all I wanted it to do, and so performing it in America fits much better with what I’m trying to say because there is that emotional immediacy to the art itself.

You mentioned Springsteen who was influenced by Flannery O’Connor, as well as REM and Lucinda Williams. Why do you think she has influenced musicians?

One of the things she talks about in her essays is her sketching, and she also did some painting. She said that sketching forces the eye to find the important lines in what you are trying to sketch, and that is true of writing in that you don’t necessarily have to pull out a fully fleshed baroque picture of what this thing is because if you draw out the major points, the major lines, you can draw a picture really quickly. Also, for her, it wasn’t so much about drawing out the moral it was about telling the story, and I think you really see that in Springsteen’s ‘Nebraska’ album. It has very concrete details and it holds back on the temptation to moralise, and even some of Woody Guthrie’s stuff such as ‘Tom Joad’, which was pre-O’Connor. I think it is just that emphasis on concrete details, which John Prine is a master of, he is there to tell a story, he is there to draw a picture, and get us to see his characters for what they are, and I think O’Connor is masterful at that in her style, and that has influenced a lot of songwriters because that is our craft too, trying to get us to see a person, a character, and a story with an economy of lines.

What does her Catholicism bring to her depiction of the South?

Georgia has a much stronger population of Catholics than most of the other Southern states, especially in Savannah, but O’Connor was very much in a religious minority at the time when she moved to Milledgeville. She was very much part of middle-class Southern culture, but she was also looking at it a bit from the outside just because of her family situation. It was kind of like that for me with what I was trying to get with the title ‘Stranger in the Promised Land’. I’ve been part of the church, I’ve been part of the military, I’ve been part of the South, but with all of these, I’ve never felt quite at home with them even though they have sharpened me in many ways. In a lot of ways what I’ve written is about someone who is in these things but is not necessarily of them, so to speak.

How did you decide to write the songs on your ‘Peacock Feathers’ EP in 2018?

A lot of my catalogue was written between 2014 and 2016 and I’ve been progressively releasing them since, and those songs on the EP I first debuted at a conference in 2015 and I got a lot of interest in them playing live at the time. I was getting out of the army at the time and I was just getting home from Romania and I had a couple of weeks spare so I got together with some friends and so I told them I’ve got four songs that go together and I’m going to lay down my parts if they want to lay down theirs, then we will make this thing happen, and they did. That little EP got quite a good reception, including a BBC producer who picked up ‘Mama, Don’t Know Where Heaven Is’ in York, and it proved a good foundation for ‘Tarwater’ which has just been five years coming. I’ve had plenty to do in the meantime, though.

Why re-record those EP songs with a band and write new songs for your new album ‘Tarwater’?

I think a lot of it was just what we added. I’m much happier with ‘Save Your Life and Drive’ because that needed to be an electric song from the get-go, and it’s turned into a sort of rock & roller where the first one was kind of bluesy. ‘Bad Man’s Easy’ sounds much better with a full band. I really liked both of the records of ‘The Cold That’s Forever’ that we did, there is just something about the sparseness of the original recording that we did with Stacey Rinaldi which I think is really beautiful, but I also love what we did with the full band sound. Getting to add Dashwan Hickman’s steel guitar to ‘Mama, Don’t Know Where Heaven Is’ I feel just brings out its roots as a gospel song. I wrote that song with a lot of gospel lyrical motifs in mind, and he grew up playing steel guitar in a Pentecostal church, which was very similar to mine.

I think a lot of it was just what we added. I’m much happier with ‘Save Your Life and Drive’ because that needed to be an electric song from the get-go, and it’s turned into a sort of rock & roller where the first one was kind of bluesy. ‘Bad Man’s Easy’ sounds much better with a full band. I really liked both of the records of ‘The Cold That’s Forever’ that we did, there is just something about the sparseness of the original recording that we did with Stacey Rinaldi which I think is really beautiful, but I also love what we did with the full band sound. Getting to add Dashwan Hickman’s steel guitar to ‘Mama, Don’t Know Where Heaven Is’ I feel just brings out its roots as a gospel song. I wrote that song with a lot of gospel lyrical motifs in mind, and he grew up playing steel guitar in a Pentecostal church, which was very similar to mine.

The sacred steel.

Yeah, that’s right. On the reprise version of it, he and our drummer just started messing about with the song, and I was like we’re taking this to church now, aren’t we? I then told them to hit record and we only got kind of the middle of it but there are some magical moments in there that really fit that piece well.

How did you record ‘Tarwater’ and who’s in the band?

We recorded all the rhythm tracks live, and the bassist Evan Campfield and I have worked a lot together, myself on rhythm guitar, and Emmanuel Rankin on drums. I wanted it all to have a very live feel, and I think doing the rhythm section that way we got that live feel. We recorded it I think in five or six days, when all the other people were available we just brought them into the studio. All the other artists, David Childers, Rebekah Todd, Momma Molasses, Dashawn Hickman, Laura Jane Vincent, and Aaron Pants, are all people I’ve known and respected for the last couple of years. I just asked them if they wanted to be part of this project, and they were all like, absolutely. It was a very fun project, and I really enjoyed the studio process. It was also cool because our electric guitarist, Bob Worrells, hadn’t spent much time in a studio so we needed time for him to find out all the tools that were available to him.

How did you approach songwriting? How do your military background and academic activities influence your musical activities?

I’d say that my academic side influences my songwriting more than my military experience. My military background helps me organise things with the band a lot more. I’ve been told I’m really organised and I say for an artist I am, but I was a horrible officer. For the songwriting, I’ve studied a lot of poetry, and for me, the lines themselves have their own music to them regardless of the instrumental music, and that’s really important to me. As well as finding those concrete details, and messing with those lines until they are ready. Am I disciplined, not really, it is more a matter of when an image or a line grabs me, and making sure I jot that down so I can come back to it later on. As far as the process, each song has its own life, one song took three years to write and some songs whip themselves out in a couple of months, and some of them whip themselves out in a day. Yeah, it varies.

Who are your musical heroes?

John Prine, definitely, in his songwriting, and earlier on Bob Dylan, and if you compare those two John Prine is Robert Frost and Bob Dylan is T.S. Eliot. Bob Dylan was dealing with these huge ideas, these visions, and he could give you concrete details that got you into the stories, but in my opinion, they weren’t the stories of the common man, whereas John Prine’s were. As with Robert Frost and T.S. Eliot, John Prine and Bob Dylan are both great, it is just they have a different focus. I think it’s also old folk tunes as well, I was in the old-time ensemble up here in UNCG, memorising these ballads and blues songs, many of which aren’t documented. Songwriters are a huge influence too, and again, they are storytelling and focusing on concrete details and they are drawing images for you. Sometimes you don’t know all of the story but there is enough of it there for you to make sense of it and give you a feeling about it. Also, Rhiannon Giddens. I love what she’s done solo and her ‘Songs of Our Native Daughters’ album. That is just a fantastic album, and I love what she’s doing not just with her songs, but also with her musical activism to get us to realise there have been a lot of people involved in these traditions over a long time, even if they are not the people the industry recognises over this time.

Do you have a view of what the potential audience for ‘Tarwater’ is?

When I came back I had three projects in my pocket, the ‘Hot Pepper Jam’ album which is already out, the ‘Tarwater’ album, and then the ‘American Inferno’ album which will probably be out in a couple of years. I was thinking that ‘Hot Pepper Jam’ is a regional album because it is pretty old-time and it is about two-thirds originals with a few traditional, and even the originals were part of that old-time genre. With ‘Tarwater’ I had the sense it might get some interest at a national level so I released the regional album first. These songs are pretty accessible even if you don’t know Flannery O’Connor, and I wrote them to be fairly personal songs too. I knew that would be added interest, whereas ‘American Inferno’ is much more literary, maybe not quite as accessible, but I still think it will be fun.

Will you bring ‘Tarwater’ to the UK and Europe?

Solid plans no, but would I love to, yes. I’ve applied for the showcase for AMAUK, and I’ve got a fair few friends in the North of England whom I’ve been talking to about bringing the band over, such as St. Catherine Child’s Ilana Zsigmond who I’m good friends with and who opened up for me when we released ‘Stranger in the Promised Land’ up in York, as well as some good friends over in Ireland too. So we’re talking to the band to try and work things out for probably late next summer. It’s nice to be rooted again, but also nice to get away and travel a bit, and it’s nice to have a home to come back to.

We like to share new music with our readers, so currently, what are your top three tracks, artists or albums on your playlist?

John R Miller’s ‘Depreciated’ album has been my dishwashing music for the last year and a half now. It’s a fantastic album, and he’s from my old neck of the woods in Northern Virginia, though he is from West Virginia. Also St. Catherine’s Child’s ‘Every Generation’ and David Childers’ ‘Interstate Lullaby’.

Is there anything you want to say to Americana UK readers?

Just a huge thank you, especially to the York musical community for my time over there. I think I got a much better view of the performance aspect and the business aspect of making music while I was studying for my Masters in Creative Writing at York St John University. I got a much better handle on this artist thing while I was over there and I would love to bring the music back soon. I’d also like to thank the radio stations who’ve been playing my music over the last couple of years, Jorvik Rado, Two Rivers Radio, Radio Troubadour up in Scotland, Rob Ellen and Kerry Fearon, and a bunch of other class folks too.

I’d like to thank and amplify those voices who were on the record, all of whom are great songwriters or musicians who I respect a ton as artists and people, and all of whom are from North Carolina, Virginia, or South Carolina. Rebekah Todd (her first two albums provided the soundtrack to my first deployment overseas), David Childers (the Avett Brothers have covered several of his songs, and he has a new album out), Momma Molasses (new album out soon, Dashawn and Wendy Hickman, Laura Jane Vincent, Aaron Pants (Lonely Superman), Christen Blanton Mack (Zinc Kings), Emmanuel Rankin (Lando Sparks, Bedroom Division), Bob Worrells (Greensbrothers, High Strung Bluegrass), Evan Campfield (Farewell Friend, Shadowgrass).