You can try to leave a small town for a grander life and adventure but beware of the Boomerang Effect.

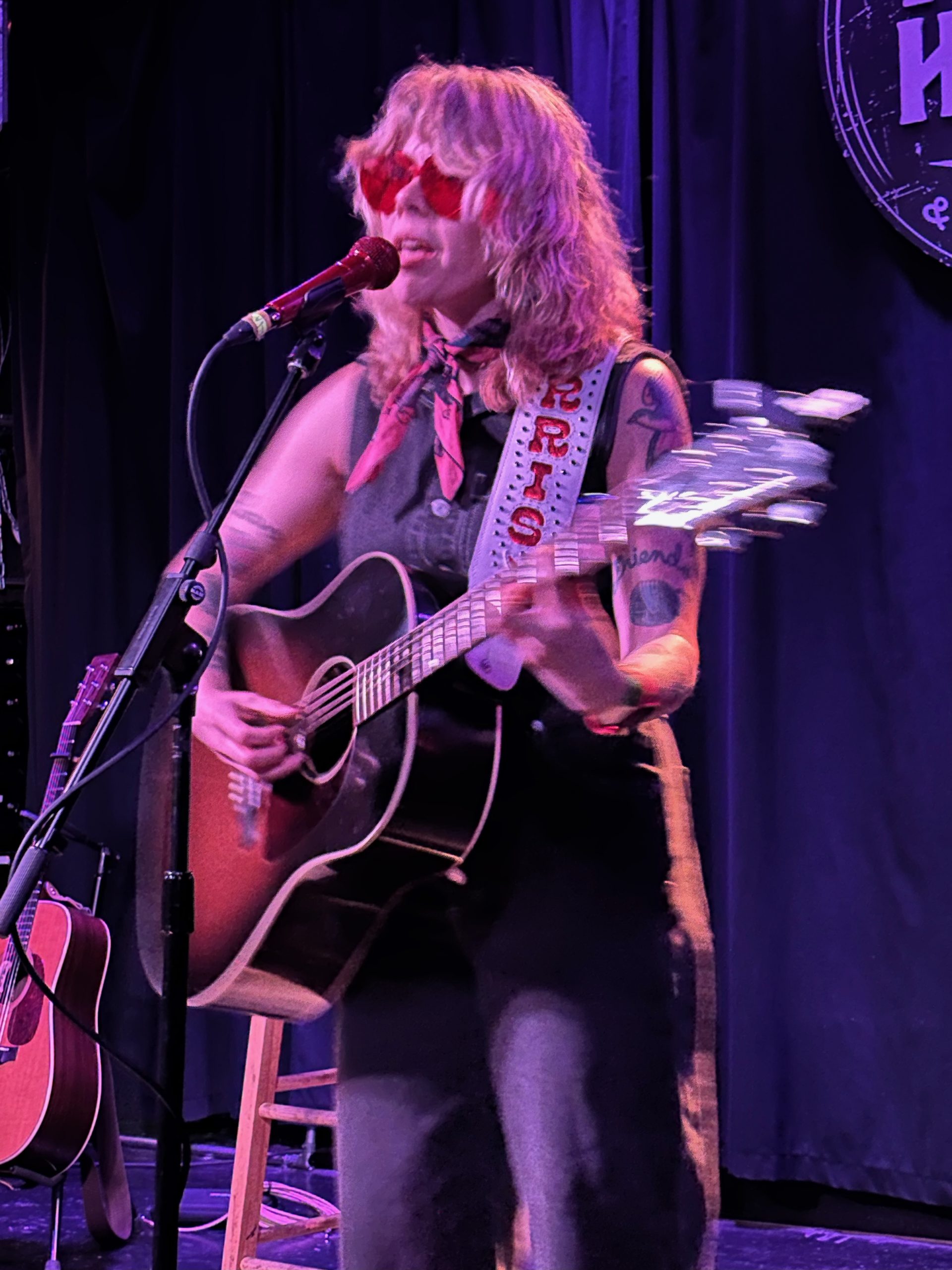

This interview was recorded while sitting on a couch in the green room one afternoon at the Pour House in Raleigh, North Carolina. Jaimee Harris talked about a variety of subjects: the pain of addiction and recovery, a Fred Eaglesmith tribute band, Mary Gauthier, Eliza Gilkyson’s house, the rollercoaster at Carowinds, hope for understanding instead of division, breaking free from what families expect generation after generation, Wes Collins’ troubles processing credit card sales, small towns and the colourful characters you run into there, her kindergarten teacher, getting sober and, not to forget, her mentor Jimmy LaFave.

Jaimee Harris’ latest album, “Boomerang Town” (2023, Folk ‘n Roll Records), sits at “the intersection of these social, personal, and political currents where the album was born,” a line from her press bio that’s worth repeating. It would be advisable that the intersection employs four-way stoplights as she tackles these topics in abandon with a seriousness buffered by her quick wit. Those currents can be turbulent in some of her songs, though she always tries to leave room for grace to calm the whitecaps encountered while swimming the choppy waters of 21st century America.

Some of what she delves into in her songs many people would rather not consider, such as addiction, death, relentless grief, murder, teen pregnancy, cancer, you know, all the fun stuff. But the way she tells the stories of these downtrodden characters allows you to think of them as survivors, and if not, at least they may find a measure of mercy.

Many small-town youths have dreams of leaving the languor and quiet desperation of normalcy from following the paths parents set out for them, a topic the author Richard Ford writes about in novels such as “Independence Day.” There are restraints to break and family and friends to draw you back as surely as a boomerang returns after being thrown, no matter how far away. Harris advises the songs are about her but not necessarily her, sometimes a combination of the two as a way of telling the stories.

Ultimately, she offers a sensitive perspective on the unpredictable events and esoteric choices people grapple with by just living their lives. How do you deny the desire to drink when your family has a history of alcoholism? How do you separate yourself from dead-end jobs and people going nowhere? Harris believes in free will and with it change is possible.

There has been enough loss in her life, perhaps more than her share, but she’s gained a measure of happiness, too. Harris enjoys a partner in life, friends, her music, over ten years being sober and a bright, expansive way of seeing the world and her place in it. There’s a profound energy and unabashed lyricism seeping from her songs like tears of joy or sadness. She sings with a contemporary vibrancy while inviting the listeners to explore the human condition along with her.

What do you like the most about being a professional musician between the songwriting, the recording and touring?

I really like being on the road. Of course, writing songs is cool because that fuels the whole thing. Maybe it’s because I grew up in a small town outside of Waco (Texas), I wanted to see the world. I was very awkward … still am … so music allows me to connect with people. It’s still exciting even though I’ve been on the road for several years. When I’m with my partner Mary Gauthier, we fly and rent, but if I’m alone I’ll just drive my Honda CRV.

Do you like driving around the country?

I really do. I listen to music, pull over and see freaky stuff, and find pinball machines. Eating at different places I like, definitely, especially if the place has pinball machines. There’s a cool app called Pinball Map. Just enter your location and it shows you where to find them. And rollercoasters, I’m shocked I haven’t gone to Carowinds (an amusement park near Charlotte) on this tour.

On this current tour with Wes Collins, you’ve been playing pretty much every night for two to three weeks with a couple of house concerts as well. You’ve told me that you think a lot of Wes and his music. (She’s right about that. Definitely check out his music.)

I connected with Wes Collins around 2015. He’s got this neurological condition called cluster headaches, which my dad also had. So, we met because of this weird thing that not a lot of people know about, and he asked if he could give me one of his CDs. I said sure and put it in my car where it remained for years until Wes put out a new record, which I begged him to let me sing on. I get to play every night with him and sing with him, and it’s such a treat. He’s in his 60s now but very childlike in a good way and fun. Even so, he’s very new to the road and it’s fun seeing the road through his eyes, and listening to the questions he asks.

What’s one of those questions?

He’s starting to get bigger audiences now, and I saw he didn’t have a way to take credit cards. I said to him, “Wes, you’re going to start selling stuff so let me help you with that.” You have to know about stuff like that.

Have you been playing the same setlist every night?

If I’m doing an opening set, I pretty much have that worked out. I have been an opening act for a lot of years, and that is a very difficult role in many ways because you’re playing to an audience who didn’t come to see you. Most of them don’t even know who you are. You have to win them over, or at least try though you won’t win everybody over. After many years, I figured out a set that works for me. I even wrote a song called ‘Opening Act.’ It’s a really good icebreaker because it’s funny and my regular material can be pretty heavy. Having that moment of levity helps also because I have trouble with speaking, (not really – DN) which is why I turned to songwriting. It helps me to communicate effectively in a form that’s thought through and edited. I spent some time working with a performance coach to get my stories down. But if I’m doing a Jaimee Harris show, there’s not going to be a setlist. I’m going to totally play what I feel like, maybe gauging the audience or what’s happening around the world. If I plan too much, I’ll end up missing a moment.

You have so far two full albums and the EP to draw from. Unless you do covers, is that enough?

I started playing when I was ten and was writing songs at 14, and my first record didn’t come out until I was 28. There’s definitely a body of work though I’m a really slow writer. In the case of “Boomerang Town,” I had a batch of upbeat more poppy songs and a batch of Boomerang-type songs, so once I wrote ‘Fair and Dark Haired Lad’ with Dirk Powell and Katrine Noel. it’s like a lightbulb got screwed in. This is how I’m going to steer the ship. So, there are a lot of songs that didn’t make either album, but I play them all at times.

As a musician, do you have any professional goals?

Actually, I never see myself going beyond the Patty Griffin level. I really admire her, her career, and everything she does. Yeah, I’d really like for Emmylou Harris to sing one of my songs. That would be a career goal. And I’d love to be respected by other songwriters in the way Patty Griffin is. To be able to play in places like the Ryman that seats around 2500, that’s as big as I can imagine. I don’t have an aspiration to be a pop-country artist. When you get beyond a certain level – and I don’t have the personal experience but from the outside looking in – it seems there are certain things required of you to maintain that don’t match my skill set. I tour a lot with my partner and she is most comfortable in a listening room with 2 or 300 people, maybe 500 like in the Netherlands or the UK. Playing at a festival with those crowds makes her very nervous, but for me, it’s exciting. Like it’s totally cool to rock, let’s do this. I do love that energy.

From what I’ve heard of this tour, you play a couple of songs then Wes plays a couple songs and you’ll do one together. That’s different.

It is but we’re not doing that tonight. Wes is going to open and I’ll jump in and sing harmony on a couple of songs, then I’ll play my set, although I don’t have any idea what I’ll play. I told Wes just come in if you hear something you know.

Let’s talk about “Boomerang Town.” I read in your bio a remark about the record being at the intersection of social, political and personal currents. Does it ever enter into your thought process when writing a song, that it may be controversial? That part of your audience might take offence, especially in these politically-charged times.

There are some artists like Patterson Hood, B.J. Barnham, and one I like called My Politic that are just better at pushing the envelope on stage with their banter besides their songs. I’m not as good with my words. Take the march on Washington when Dylan just played. John Lewis spoke. That’s not me. My mission statement is to bring people together. One thing so frustrating about the times we are living in is the division. The real lie is that we have less in common than we do. Guy Clark used to say “We’re all living the same lives; we’re just hitting the marks at different times.” So, I’m not out there to change anybody’s mind. My mission is to tell a story. For example, I’ve got this song that hasn’t been recorded yet called ‘Tattoo Zoo,’ and it’s a story about three different people getting tattoos in a tattoo shop. I had a woman send a message to me that said her son has been a tattoo artist for 15 years and she never understood what he did. That song helped her to understand. So, I believe in just telling the story and giving people the agency to create their own meaning. That’s the power of song. Sometimes it does open minds.

Earlier you mentioned ‘Fair and Dark-Haired Lad,’ which is a standout track on the album. How did you happen to collaborate with two other songwriters on that one?

We were at the Southern Songwriters Festival in Lafayette (Louisiana). It’s co-sponsored by the Buddy Holly Foundation in Texas. They bring in songwriters from all over the world and put us in a hotel for a week, mixing us up into different combinations each day. One day I was with Jim Lauderdale and we wrote a song (‘We’re All We Got’) that ended up on his “Game Changers” record. I also got to write with Leslie Satcher, who is so much fun. I found out she wrote one of my favourite Willie Nelson songs. The song we wrote was called ‘Slow Groove,’ and it was recorded in Ireland by Brian Deady.

I’m assuming Dirk Powell was another of your writing partners there.

Dirk and I were put together on the last day, and we only had two hours instead of four. That was a lot of pressure. Earlier we had a conversation in the van about addiction, and he encouraged us to follow that into the song. I’ll never forget what happened while writing that song. I don’t believe I’ve ever told this story before. Well, I had my first drink before I could drive and the song was going to be about that. It was initially daddy left the bottle on the counter half full, but Katrine said what if it was Mama? We all got chills and said, “Yes.” That steered the song into a more interesting place.

I’m picking up a sense of grief in ‘How Could You Be Gone.’ Tell me what’s going on there.

Mary had a very good friend, Betsy Moran. They hiked a trail in Nashville every day. Betsy was the most fit person I’ve ever met, but she got bit by a Lonestar tick while hiking and it activated this auto-immune disorder called ALH. You don’t know you already have it until it’s activated. In a matter of days, she was in the hospital. This was during the pandemic. Betsy was so full of life in the Nashville music community. She’d take her young kids to Pride, and say check this out, it’s a different world than we’re in. She was just an incredible woman. We went to this outdoor funeral that was surreal. It was like we were waiting for her to walk in. We were in the early stages of grief, and Mary said why don’t we go sit by the fire and try to write to articulate our feelings?

Jimmy LaFave was another person close to you who died prematurely.

Wes and I were walking today and when we went over a bridge, I said Jimmy LaFave would have loved this bridge. He would have photographed it. I think about Jimmy every day, like when something great happens I reach for the phone to call and share it with him. It’s been seven years, and I still have a hard time believing he’s gone. Mary and I blended the experiences with Betsy and Jimmy and what came out was ‘How Could You Be Gone.’

Have you ever felt his presence around you since he passed?

Definitely. I’ve had a lot of death around me, but I’ve never felt anyone’s presence except for Jimmy. I felt it in my chest when he was dying, too. I opened my eyes and it was like he was staring at me. I thought, woah, this is freaky. Actually, I just finished a song about this experience called ‘Your Ghost.’

When you have time to do a mini-gig for AUK, you’ll have to play the song.

You got it. I went to Cassadaga. It’s like this spiritual community in Florida where I was while on this project to write a song in each town. Some people in town were scientists, telling me how matter cannot be created or destroyed, so that wouldn’t be insane to think a spirit could be there. Near the end, one woman asked if anyone was smelling pancakes. I said “I do, I smell pancakes,” thinking everyone else was, too, but turns out I was the only one smelling them. She asked me if there was any significance to that. I said that Jimmy and I always got together at a diner. After, I went to her and said, like I told you, I’ve had a lot of losses in my life. Jimmy and I were friends but not like extremely close. He got me, though. This is so much. I’m gonna start crying. She told me he probably only comes when you need him. No one’s ever brought this kind of thing up to me, ever. I don’t think it’s weird at all. It’s beautiful.

I noticed a table set up for SIMS on the main floor.

Right. The show tonight is a benefit for an organization that started in Texas called the SIMS Foundation. They help musicians get access to affordable mental health care and substitute recovery services. Tonight, I’ll probably talk about my struggles with depression and addiction, my joy in recovery and my experience with the criminal justice system. It’s funny when sometimes I’m on stage with this dude all burly and tattooed, and one of us has been to jail and one of us hasn’t. Someone might think it’s not me, but I’ve been to jail …. twice, and here I am. But if you go on social media, you’ll know how I lean politically.

Do you find it difficult to converse with someone who leans in the opposite direction?

No, I can talk with anyone. I am concerned with not leaving space for mercy and grace. As someone who’s an addict, I’ve had to make amends for things I’ve done in my life that I’m certainly not proud of. It’s been ten years, four months and one day in recovery. So, if we were judged by the worst day of our lives or something we said that wasn’t fully formed or could be misinterpreted, that would be devastating. I wouldn’t be the person I am today if someone hadn’t said to me, okay, you’ve done this, let’s move on. I think a lot of what I’m up to in my songs is alchemizing those experiences.

It sounds like there’s a song in there.

You’re right actually. What I’ve been thinking about is a song from “Boomerang Town” called ‘On the Surface.’ One time I ended up at Eliza Gilkyson’s house outside of Taos, New Mexico, but I started in Terlingua on the Texas/New Mexico border and then I went to the Woody Guthrie Folk Festival in Okemah, Oklahoma, and after that drove to Eliza’s house. In 2016 I was living in a very liberal community, and people were saying oh, the Christians did this or they think this and I can’t believe they blah, blah, blah, and I was like well, am I still a Christian? I don’t think the way they say Christians do. But I don’t like that generalization. That doesn’t apply to my mother. And I know there are people in more conservative areas that say things about liberals, and I just think it’s more nuanced than that. And that’s what I was trying to articulate in the song. I’m someone who’s experienced redemption, and it didn’t come from intellect. It came from surrender, something outside of myself that I don’t feel the need to define.

“Boomerang Town” is populated by characters who are struggling with their emotions.

Thank you for saying that because in a lot of songs I’ve written, I am the narrator. When my partner and I teach songwriting, we make the point that a little bit of distance, even if it’s you in the song, the you from ten minutes ago or ten years ago, it’s not you that allows songwriters to go deeper. I truly try to write from behind the eyes of a narrator that isn’t me intentionally, but with ‘Boomerang Town’ I had to allow it to be me in order to get that song to do what it needed to do. I started with myself and then I tried it from behind the eyes of a waiter who works in a diner in Crawford, Texas and that didn’t work. Finally, I landed on the narrator as a 17-year-old boy working at Walmart. I did work at Walmart for a while, so I knew about that but it was surprising to learn that was the most accurate way for me to express the experience of growing up where I did. Somebody else needed to talk.

Well, you find inspiration in the strangest ways sometimes.

We were talking last night about a band we played with in Lynchburg, VA last night called The Honey Dewdrops, and it turns out they started a Fred Eaglesmith tribute band called The Bottom Rung, which I think is the coolest thing ever. They sing this song ‘Katie,’ you know that one? It’s from the perspective of a man who catches his wife cheating on him so he kills her. And we’re talking about the genius of Fred making us empathize with the murderer. He says this brilliant line in the song, “The gun goes off.” He doesn’t say, “I shot her.” It’s the gun that went off.

It sounds like he was writing about Alec Baldwin on the set of a movie, you know, the gun just went off, not Oh my god I killed her.

(laughing) I hadn’t thought of that but of course. The genius of Fred. What a masterstroke! That’s a yardstick for me.

When musicians write a song, often it’s about what’s going on in their lives or in the world. There was a five-year gap between “Red Rescue” and “Boomerang Town,” two albums with very different subject material. What changed during those five years?

Oh, just about everything. “Red Rescue” came out in 2018 but we started recording for it in 2016. I was new and wrote a lot of songs back then. Because I’m really good at editing and tend to go over songs several times, it takes time to finish one. Like one word can make a huge difference to me. I got better at writing during the years before “Boomerang Town.” But everything in my life changed. I went from working at a medical office and playing clubs in Austin to quitting my day job and going on the road full-time with Mary, moving to Nashville, and seeing more of the world. Hopefully, I’ve grown as a person and it’s reflected in my music as well.

Some learned music scholar once wrote about each generation having a unique way of expressing itself in song. As a Millennial, what do you think about that perception?

I don’t think it’s a generational thing. I write about lots of different things and as I said before, I’m not always the narrator. But turning to music instead of going to college was surprising to many of my teachers. My kindergarten teacher Mrs. Taylor, (God bless her, she still follows me on Facebook) was very close with my high school English teacher, who recently passed away. I got burned out because my high school didn’t do block scheduling like a lot of schools do now, so I was at school from 7 o’clock in the morning until 5 o’clock, and I was also heavily involved in the church. I was told that was what I needed to go to State College. The cost of college was …. well, inconceivable even back then. The concentration of wealth in this country, even ten years ago, is brutal. In 2009 when I was playing coffee shops, there were people with Master’s degrees and graduate degrees working as baristas.

You must have thought, that could have been me making super expensive designer coffee drinks.

In some ways, I feel like I’m living this Peter Pan life with this music thing. I can’t believe this is my job.

Jaimee Harris’s “Boomerang Town” is out now on Thirty Tigers.

Jaimee Harris’ music and tour schedule can be found here.

The SIMS Foundation provides mental health and substance use recovery services and supports for musicians, music industry professionals, and their dependent family members. Through education, community partnerships, and accessible managed care, SIMS seeks to destigmatize and reduce mental health and substance use issues, while supporting and enhancing the wellbeing of the music community at large.

Jaimee Harris, Wes Collins and Dean Nardi support the SIMS mission. Find out how you can help by going to their website.