How jams at the back of Bob Dylan’s tour bus and Levon Helm’s Barn helped a personal relationship become a musical one.

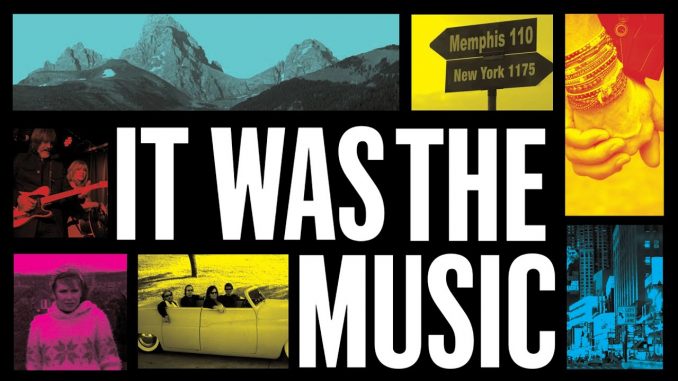

‘It Was The Music’ is a 10 episode documentary series by director Mark Moskowitz that celebrates music that has been close to his heart for all of his adult life and also changed the world. Moskowitz had wanted to make the documentary for some time but was struggling to find an overall concept that would be a suitable vehicle for him to explore and celebrate the mix of rock and roots music that emerged in the ‘60s and ‘70s and continues to influence the music of today. It was when he attended a gig by Larry Campbell & Teresa Williams and heard their roots inflected music and saw the close connection they had with their audience that he found the solution to his problem. His documentary series features Campbell and Williams as they traversed America playing their music and includes a host of interviewees and never-before-seen performances with friends including Jackson Browne, Jorma Kaukonen, Jack Casady, Phil Lesh, Jerry Douglas, Buddy Miller, Rosanne Cash, David Bromberg and others.

Larry Campbell may have been born in New York, but he has doggedly followed his own musical path that tracked closely to the various sounds of the American South. This personal journey has found him working with a whole host of artists as a session musician, producer, bandleader and arranger, many of whom appear in the documentary, and he has had long-term musical associations with Bob Dylan, Levon Helm, Jorma Kaukonen and Hot Tuna. Teresa Williams is a successful actress and singer who has also been married to Campbell for thirty years and while she may have made her home and name in New York, she has kept her Tennessee roots front and centre and helps keep their music honest and real. The couple have released two albums, 2015’s self titled debut and 2017’s ‘Contraband Love’, both of which are prime examples of the full range of American roots music with original material and a few well chosen covers.

Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Larry Campbell, Teresa Williams and Mark Moskowitz to discuss ‘It Was The Music’. This first interview is with Larry Campbell & Teresa Williams and looks at how they agreed to be in the documentary series and how they adapted to living with a camera crew, they shine a light on their work with Levon Helm as he rebuilt his career in the 21st Century, explain how playing songs together at the back of Bob Dylan’s tour bus eventually led to their own joint career and the live musical challenge of trying to follow the music improvised by Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady. Teresa Williams explains how her mother was not particularly impressed when she was taken to a Bob Dylan concert in Nashville with Larry on guitar but was overjoyed at the Levon Helm concert at The Ryman, particularly with her daughter performing on that hallowed stage singing a song Teresa had originally learnt from her father when she was a child, ‘Long Black Veil’, with Levon Helm. Larry and Teresa also share there experience of Larry’s serious COVID infection and their sadness at John Prine’s subsequent COVID related passing.

Hi both, where are you?

Teresa Williams (TW): I’m in Peckerwood Point, Tennessee.

Larry Campbell (LC): I’m in Woodstock, at our house in Woodstock, New York. I’m about to get in the car to head down to Tennessee. I should be there already, We should be on the couch together [laughs]. I got my second COVID shot last week which kind of knocked me out of the ball game for a while and I had stuff to catch up on, but I’m leaving as soon as we are done here.

You actually had COVID, didn’t you Larry?

LC: It was awful, it was about a year ago around the beginning of the whole thing.

TW: It was very scary for me. He should have been in the hospital, but it was a scary time to go to a hospital and he was just refusing to go, and just when we were about to make him go his fever broke, thank goodness. I kept thinking I wasn’t going to wake up with a husband and I wasn’t with him I was in New York City, and he was alone in the house. The day when he got better, the day when the fever broke, because he had had the fever long enough, he has a cousin who is a nurse at Columbia/Pres which is one of the best hospitals in New York City, and she said, “You are at the stage where people’s organs can shut down and then, I hate to tell you, you die.”. We were trying to get him to go to a hospital and the next day, when it broke, I just crashed with the grief, the fear and everything, and I said we have truly walked through the valley of the shadow of death. That is the closest experience, I had had a brother who died suddenly many years ago, but I had never experienced anything like that daily not knowing if you are going to wake up with your spouse still alive. My heart goes out to all the people who didn’t have the outcome that we have had.

There are a lot of people in America, the UK and throughout the whole world who are, unfortunately, in that position.

TW: Yeah, there really are.

LC: The most significant for me was when John Prine’s wife, Fiona, heard I had COVID she was texting me with best wishes and then a few days later John got it, and shortly after that he was gone. That one really hurt, they were so sympathetic to my situation, and I made it and he didn’t.

It really is a shake of the dice, there is no rhyme or reason to it.

LC: No, that is absolutely right.

TW: Even the aftereffects my brother and Larry are experiencing, it is bizarre, the randomness is also bizarre.

It is a new disease and even the doctors don’t know the longer-term implications and how and why people are impacted differently. Hopefully, we are beginning to come through it.

LC & TW: Yeah.

Right guys, you are the stars of a documentary series ‘It Was The Music’. How did that come about?

TW: [laughs] We were the guinea pigs. You tell him, Larry.

LC: Teresa and I were playing at a place in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, and we did our normal show and it was a pretty good night. Afterwards, to sell CDs, you go to the signing table and this man came up to us and said he loved the show, loved what we were doing and that he was interested in filming a documentary. The way he explained it in the moment was that he was enthralled by the way we were doing this thing on stage and it was connecting with the audience who were giving it back to us and us to the audience again, and he wanted to make a film about that if we were willing to be the protagonists in it. He was friendly, he was nice, he was complimentary, so sure and we were expecting nothing because we hear similar things and that is the end of it. He followed through though. The next week we were playing in New York City, he showed up and he was very aggressive about making this happen. Teresa and I talked about it and it was like what have we got to lose [laughs]?. We had a good feeling about this guy, Mark Moskowitz, and we just figured we will follow it and see where it goes. There it was, the next thing we knew was we had cameras following us everywhere.

A question for you Teresa, you were wondering whether this interview would be videoed, what was it like having cameras following you a lot of the time? How did you cope with that?

TW: The worst part of it was that we were on the road so much that inevitably it would happen when we had just pulled in after doing eight shows in a row in a different town every night, in our little car, or whatever, and we would pull in at maybe 2 in the morning, and then you would have the cameras in your house all day the next day. I said there should be a wall of fire at the beginning of the film that said she is weeping so much because she hasn’t had any sleep [laughs], because of all these interviews [laughs]. We had the camera following us around for 2 or 3 years with the Levon documentary as well, didn’t we Larry?

LC: Yeah.

TW: So we probably got immune to that. By the time we were really rolling on this, Moskowitz had become some kind of a friend as well as his crew, so it was kind of fun having them around and you kind of forget that they are shooting this and I should be watching what I say [laughs]. So I guess that is the best way to do it. My mother is still going I wouldn’t let them do that, so this is both sides right there. People are like how do you deal with it now it is out there and I am just like I don’t care. My little quote is “It kind of frees you up some”.

LC: You know the thing, he really did an honest depiction of what our life was like during those couple of years, you know. You can’t argue with that, as far as I’m concerned if there is an artifice or stuff made up, or a slant to make it look a different way, that might have been a problem. I think he really put his heart into it and wanted to depict, as honestly as he could, what he saw in Teresa and I and our ability to communicate through music.

He certainly pulled that off. You are a New Yorker Larry, why were you drawn to what is now called americana, but at the time was simply rural music?

LC: It is honest.

TW: Wait, wait [laughs]. That was my exact question when I first heard him play. I didn’t even see him at first, it was at this little rehearsal, and I had hired him, I just had this one little set I had to do with a country band, and I didn’t know any country musicians in New York City, and a friend got him and other crème de la crème players in this band for me. I get to the rehearsal, I’m really, really nervous and I didn’t think these New York musicians would be able to play country music. I had a Hank Williams medley, and he was playing pedal steel and I heard him, and I’m like he is saving my life whoever he is, he was inside the music. For days I was like how, why, when did you, I mean pedal steel and you are so inside it? OK Larry [laughs].

LC: I was always deeply moved by music, ever since I can remember, I mean deeply moved. My parents had this really eclectic record collection covering Hank Williams, The Weavers, The Harry Smith Collection all this stuff like southern country and blues along with opera and Frank Sinatra and all the contemporary stuff from around their time such as big band stuff. All this was on constantly in my house and I would subconsciously absorb it, but the big bang, and I always say this, was 9 years old and your countrymen were appearing on The Ed Sullivan Show, February 9th, 1964. The Beatles just kind of blew the doors open and it was my entry into solidifying all this exposure I had had to music up to that point and giving it focus. Like everyone else at that time, I was obsessed and the world changed.

Listening to these Beatles’ songs they all have a familiarity even though it is random music to me and eventually I was able to analyse it and a lot of it is coming from the skiffle genre, that was present in England before them, which came from American roots music that I had been absorbing and exposed to until then. Through the ‘60s it was such a fertile time for American pop music, world pop music come to that, but the stuff that really spoke to me was the stuff that came out of the dirt of the southern states of America, you know. The blues, the gospel, the country, the bluegrass, the folk music and all that stuff, and when the Beatles did ‘Act Naturally’ I thought I was going to explode, [laughs]. Here they were playing this happy country tune and I noticed it was written by this guy Buck Owens, so I looked him up and started going way down that path, Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, George Jones and then the women, Tammy Wynette and Loretta Lynn. I couldn’t get enough of it and there was something about the lack of pretension and the organic mode of expression that is in this music of The South, it just bowled me over, and I had to follow that path the rest of my life whether it was literally that route or anything that had that element that was an offshoot or growth of those genres.

Why stay in New York City, why didn’t you go straight to Nashville and have done with it?

LC: In the early ‘70s I realised I was pretty much a loner in this way in New York City but the whole California country thing with Poco, the Burrito Brothers, the Byrds and what they were doing, that was a real magnetic thing to me, and I had this romantic vision that if I go to California I am going to be immersed in this stuff, and it is going to be great. I got into a car with some friends and no money, and we headed to California [laughs]. I lived there for a while and I eventually got with a country band there and we started travelling and I ended living in Jackson, Mississippi, for a couple of years, which, having had that experience, is the only reason Teresa was able to marry me. I managed to absorb her culture, you know.

TW: That’s true, I wouldn’t have even considered it if I thought that the divide was too deep between New York and where I am from. It is perfect extremes, opposites, and even when we were dating, I still was concerned that it was too deep a cultural divide, but I couldn’t walk away from him [laughs].

Because you came to New York City as an actor, didn’t you Teresa?

TW: That’s the reason they told me. I grew up on all the music Larry talked about, I just absorbed it at my parent’s knees. I took all that for granted, Nashville was just two hours up the road from me and Memphis in the other direction, I was like Larry in that I was passionate about it and deeply moved by the music coming out of the Roger Earl station from Memphis, which was a fabulous station and they were known for being diverse, just playing all kinds of stuff. I don’t know where the thing to want to act came from unless it is the telling of a story, it is all storytelling to me. It is as if I grew up on Mars that I wanted to go and study acting, but I did. My teachers were so naïve, my high school advisor said to me as I was about to go out the door, “Well you realise you are going to have to go to…” because there was no acting in my school of course in rural Tennessee. There was barely a senior play, that was the extent of the whole thing. Goodness only knows why I was marked for this, and they said I will have to go to New York City, I was like I don’t want to go there I don’t want to leave home. They said “You have to” and I finally did, but I always had the music thing, it was always a covering around it and I was considering it as another path and I think I knew I didn’t have the personality to handle that scene in Nashville.

I knew one girl who had gone there to make it in music, and I just knew I could sing and I sounded like the people on the radio, OK, you know, but I don’t know, just right in the moment that’s all I know and straight-up acting was it, I wasn’t in it for musical theatre though I love musical theatre. In New York, I was on the acting trajectory, but on the peripheral, I was always needing to be in the music industry side of things. I got to a point with theatre that seemed like I would invariably be cast with something that had music in it, mountain women or something, I ended up being typecast [laughs]. They would say well we have mountain music in this and it is the real thing and I would think whoa, Sarah Carter and farther back with the English ballads, and I was thinking this sounds really interesting and I would get there and there would be Dylan knockoffs or Neil Young knockoffs, and I just felt this is not right, maybe the plot would be good but the music would be bad. It would never come together, and I just couldn’t stand it. I would take jobs, like in South West Virginia, just so when I got out of the play I could go play with the local musicians. Going to places in plays I maybe didn’t like, just to play with local musicians, it was just starting to come together.

What are the dynamics of Larry and Teresa? How do you work together musically?

LC: Good question. Well.

TW: Larry does everything, all the heavy lifting. I have come to visit my parents and he has said show up, in so and so we are going to do blah, blah, blah, like upcoming now we are going to record a little thing in Muscle Shoals, and I just show up and sing, basically. That is the truth [laughs].

LC: That may be the way it is now, and I am certainly the more aggressive one in this musical relationship and the writing is usually mine, but my writing gets filtered through Teresa’s approval usually. Or her editing.

TW: Stop. I have some strong opinions [laughs].

LC: The thing is from the day we met, and nothing has happened to damage this opinion, Teresa is straight ahead, you know. If something doesn’t smell honest and real, she is going to know it and I need that objectivity, as subjective as she may be because of our relationship. She is always going to tell me, one way or another if I slipped into some sort of an artificial expression, something I might miss. Writing to me is really hard, and is laborious, and getting involved in that labour it is really hard to stay focused on the true feeling that you are trying to express. If I miss the ball, she is going to tell me [laughs].

TW: You know, talking about that authentic thing, my parents get the RFD-TV satellite channel which is like a rural TV channel and on a Saturday Night they still play all of these old shows that I watched when I was little, on Saturday Night. The Wilburn Brothers, sometimes Porter Wagoner will appear on other shows, and they maybe will play The Porter Wagoner Show, The Holme Brothers, who else Larry? They have Marty Stuart, which is great, and the old Gannaway films of the old Opry stars which are just fabulous, oh my gosh they are so fabulous, and I think Larry has had them for a while but to see them again and sit there with my parents because I’m with them during the pandemic, like I did when I was a kid is just so great. The other night on The Wilburn Brothers they say we have been trying to get Roy Acuff on here for years, five or six years or more, and they finally got him on and it is “Here’s Roy Acuff” and the transition from the early Opry days over to the years of Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn and those people. He comes on and just the authenticity of those early day raw kinds of americana music was startling next to even The Wilburn Brothers. It was so raw, and it was like having Ralph Stanley back up there on stage and he played the fiddle and he said, “I haven’t played fiddle for a while and I decided I’m going to play again so I started practicing every night, you know, 30 or 40 minutes, so I’m going to play for you today.”. It was just so raw and intense I can’t express how the contrast from Roy Acuff’s era to The Wilburn Brothers era to a few shows later in the Marty Stuart era, it is just fascinating every Saturday night [laughs], they are still running these. The rawness of Roy Acuff, now Larry can play a mean fiddle and my complaint sometimes is you know you sound really good but just sometimes I just like that raw thing. Everything gets filtered through your life experience, and there is a local guy here Stanley McAdams who plays a fiddle that just breaks my heart, and he is not a professional and he is probably not as finessed as other fiddle players, but it will just get you to the core, right Larry?

LC: Yeah, and that is the thing you try and hold on to as you progress as a musician.

TW: Me too as a singer, same thing.

LC: You try and keep a hold of that thing that comes from just this pure expression that has nothing to really do with training or finesse.

TW: That’s called a soul [laughs].

LC: All this music we are talking about and that we are absorbed in, the roots of that go back to you guys over there.

TW: Back to the ballads, exactly.

LC: And sometimes out here these old British or Irish or Scottish ballads, I don’t know, where does it come from? It is like someone felt something and this is what came out. As you progress as a musician you try, and not always successfully, to capture that thing and not let it fade as your ability to play your instrument increases. If you can do that then I mean, there have been so many great musicians over the last decade that were able to really stretch the envelope of what is good bluegrass or country or fiddle music. The prime example for me is of course Mark O’Connor, every time you hear him play you still hear the guy with the axe on his shoulder walking through the woods, and as sophisticated as he gets, that is still underneath his playing and if you can hold on to that and still expand the vocabulary or break down the walls of that genre, then you are really doing something.

You waited until 2015 for your first joint release, apart from an earlier instrumental solo release of Larry’s. Why did you wait so long?

LC: Well, OK. Our thing, what Teresa and I do, took a while to develop. When we first met, we started singing together just for the fun of it and that was thirty years ago, but Teresa had her career, and I had my career and we diverted but always with this thing in mind that we like to perform together. Shortly after we married, I am out on tour with Bob Dylan for eight years, and Teresa is out doing her plays, and she would come sometimes if she was free, and we would sit at the back of the tour bus and play music together.

TW: Not with Bob but the other band members [laughs].

LC: This was great, you know, just great. It is a long story, but I leave Bob’s band and a few weeks later I get a call from Levon, who is just beginning in so many ways a resurgence of his career, and he was like I hear you are free, come up to Woodstock and let’s make some music. That was the beginning of almost a decade of some of the greatest music-making of our lives. Soon after that, Teresa is involved in it.

TW: Levon’s daughter Amy brought me up to Woodstock, Larry thought because of nepotism he couldn’t really bring me up [laughs] but Amy brought me up, so it was fine. It was then just wonderful.

LC: It was, and this whole thing with Levon was that he wanted everyone to contribute, he wanted everybody involved and it just developed into this wonderful musical community. It gave us an opportunity to do what we had been doing in the back of the bus in front of people and for me, it was the coolest thing that ever happened. We are playing this great music with this great band, and we are doing it together and we have these moments when we can explore what our musical partnership might look like. This developed more and more, and then after we lost Levon it was what are we going to do with our lives now. We both wanted to pursue music.

TW: We had already started the record ‘Larry Williams & Teresa Williams’ and Levon is on it and Larry saved one of the ones that come out on the second record ‘Contraband Love’ that he is on, and we had that stuff already. We had made a start to it before he passed, and Amy was starting her solo career and lots of people in the band were starting solo projects before he passed. Most of them had their own bands anyway.

LC: Levon’s death was the catalyst for us to just jump in the water, you know, let’s do this. It is kind of a late start to take this shift in careers, but we have been professional musicians our whole lives, you know. This is not like a new occupation it was for us a new, fun, interesting and cool way to move on from what we were doing. I needed the time to develop as a songwriter, to have something to say as a songwriter, to focus on gathering material for us to do what would represent who we are and what we have to offer, and I guess from my standpoint I just wasn’t ready until I was ready.

You have played with some of the greats and going back to what Teresa was saying, the work you did with Levon is probably the best of his career, isn’t it?

LC: Many people think so, and it probably was because he was at a point in his life where all he wanted to do was have a good time playing music and make good music with people he wanted to be around. It was the same for all of us.

In the ten years you were with Levon your own skills seemed to have developed. Can you tell me how your arranging, band leading and production skills developed Larry? Teresa, you also seemed to come more to the fore during this time as well.

LC: Yeah, I think that is true. Teresa has coined that time we spent with Levon as music nirvana, and she said it was like a child’s sandbox for musicians. You could just go in there, jump in and create, be creative and feel creative, there were no restraints and no parameters and if it felt good just do it. Levon from the very beginning expressed full confidence in me as a producer and as a bandleader.

TW: Larry had worked together with Levon on the Dixie Hummingbirds record ‘Diamond Jubilation’ which Larry produced and it is one of my favourite records he has ever worked on ever. The confluence of serendipitous events around the making of that record, one of them being reconnecting with Levon for Larry. Just so many things in the course of that project would just blow your mind as far as the sequence of events. Amy and Levon listened to that record as they travelled down from Woodstock to Arkansas to visit their relatives right after they made that record. They listened to it all the way down and all the way back, and Larry had also produced Ollabella, Amy’s band, and they knew they wanted Larry after that road trip to Arkansas. I loved hearing them tell that story and it is that kind of record, I never tire of listening to that record.

LC: Your assessment that that time was really fertile for both of us is right on. It was the best musical situation either of us had ever been in up to that point. We were with this guy Levon who, if nothing else, has always been a completely authentic and honest musician where everything that comes out of him, there is no distance between who he is and what he expresses and the way he expresses it. He is sitting there at the helm [laughs] of this thing and we have complete freedom to try or do anything. We are surrounded by this incredible band where every musician in that band was a bandleader in their own right, and this happens every Saturday night, and then we have this studio we can go into any time with no pressure and no deadlines to meet. You just try and put down some good music because we are having a great time doing it, and this is something I have strived for in the whole of my career, and here it is coming to fruition. Also, the person I most want to be with me in the whole world is right there next to me doing it with me. I can’t imagine a better situation.

After The Band disbanded Levon worked with great musicians and in some great studios, but that early part of his solo career didn’t quite seem to deliver on expectations nor stand up to what he achieved with The Band. Why do you think the latter part of his career was so successful?

TW: During the early days of The Band, they were young and all fresh and fertile and then they devolved into the drugs and alcohol, most of them, and the tragedies that came with that. That will dissipate your focus, won’t it? He had those dark years of deep dissipation and I think that is why that feels darker and less potent than the early years. Then the answer hits, he had the acting stuff going on as well and then he has the cancer, and he is thinking he will never sing again or even speak with his own voice. When he pulled out of the cancer it was the phoenix rising out of the ashes. It just says a lot about his grit and determination because his first doctor told him he would have to have that box thing and he went to a different doctor in the city, I see that doctor now myself, and whatever happened during that period focused him in a way that just opened him up.

I complained to the director who followed us around for the ‘Ain’t In It For My Health: A Film About Levon Helm’ documentary that they weren’t going to Arkansas, I was like you have to go there, you can’t do this without going to Arkansas, it just informs everything. It is the root of everything about him. They were like he doesn’t want to go, he doesn’t want us to go, and finally, it came out that he wanted that project to be about going forward, he didn’t want to go back he wanted to go forward with what is happening now. I was blown away, I got it, and the same in California Larry when we were playing in The Greek Theatre, and they kept pressing him and pressing him to bring Robbie out, and he was like well next time, next time we are here, we will then maybe. He wanted to establish what his project was now, he was moving forward instead of holding on to the past. I thought that is a real artist right there, he wasn’t resting on his laurels.

He certainly did. When you were with Levon, was that the first time you had played The Ryman?

TW: Not the first time I had been there but the first time I was on the stage. It was a big deal for me. For my people here in West Tennessee it was mega, just mega [laughs].

LW: I had played there with Dylan before that and with K D Lang and a couple of people but playing there with Levon was the greatest experience I have had at The Ryman, because of who he is and the people who came and played with us. You take the history of The Ryman, the character of The Ryman through all those years, and Levon, even though he wasn’t a country artist, he fits in perfectly with everything that thing was ever about. We got Sam Bush, John Hiatt and Sheryl Crow, Buddy Miller and Emmylou and all these people up there with us. It was fantastic.

TW: For me, all of that was great and fine, but peripheral to me because one of my songs that night was ‘Long Black Veil’ which I learnt from my father growing up. For my parents, who first took me to The Ryman when I was really little, it was such a huge deal for them. I was playing a guitar that Levon had given me, a red Gibson, and my father who taught me the guitar is in the audience and Levon made me re-learn the song in The Band version, it was just a full-circle moment, and I was able to be there and enjoy it. It wasn’t about nerves, I was just able to bask in this beautiful full-circle situation with Levon over here singing with me. It was one of life’s moments, it really was. All those other wonderful people who played, that was great, but it was peripheral to that moment for me [laughs].

What did your family say when you met them after the show?

TW: They loved it, and they went to see Larry play the War Memorial Auditorium with Dylan a few years back and my mother just didn’t get it. Dylan wasn’t wildly popular around here the way he was in other areas, so they knew the main stuff that had been on the radio, but it wasn’t their thing, and my mother was like you couldn’t pay me to watch that. The Levon show they just loved because it had all these different elements, we did gospel, the country stuff and the rock’n’roll but she just loved it.

LC: When they met Levon it was just like a family member to them, you know. He was like someone they had grown up with from the same part of the soil.

TW: That was a big thing when he passed in Woodstock, having him in Woodstock it became a personal thing as well as a music thing because it was like having a relative, my uncle or somebody, there with me. We would sit around the fire on Sunday nights with him and his wife, me and Larry, just like I did with my grandparents and just tell tall tales. He hooked up with my uncle who was built just like Levon, grew up on a farm and could tear down a tractor and put it back together, so they bonded over all this stuff. My uncle was a bad alcoholic and Levon would always ask about him, even when he was in the hospital and my uncle had just passed and I didn’t want to tell him. Levon said he would have been my uncle if he hadn’t found his music, the alcoholism and all that. The music pulled him out and he would say that constantly, you come in depressed, sad, sick or whatever and by the time the show is over because of the music you will be up, and he was right.

Those are great memories of Levon. Your work with Jorma Kaukonen, is that following anything like a similar track?

LC: Oh yeah.

TW: I think you’re right. I hadn’t put that together.

LC: One of the greatest human beings that we have had the pleasure to know, and Jack Casady. He has never lost that childhood, that 11-year-old enthusiasm for great guitar playing and it is just infectious when you get around him. He is so easy to work with, so inspiring to work with. Him and Jack, they still tour like they are kids, you know. They are like decades older than Teresa and me and….

TW: Not decades, but older than us [laughs].

LC: They are older than we are and we went on tour with them a couple of times and it was so hard to keep up [laughs].

TW: You just can’t keep up with them, this was just one long weekend and I said you just push this hard all the time and the road managers goes “They do” [laughs]. Jorma’s quip is “Why would I retire, just to play more guitar?”.

LC: When I was a kid and started playing guitar Jefferson Airplane were huge to me, I thought that band was amazing. Pete Seeger had a weekly television show on PBS in America ‘Rainbow Quest’ and you would have all these great folk artists on it, and one week Donovan was on as the headline guest and there was this big blind black man, who I had never hear of, called Reverend Gary Davis and he got on and played a couple of songs and it just blew me away. I had been playing guitar for a couple of years and this was something I had never seen before so I went to the library to borrow a couple of his records and tried to pick them apart, but I couldn’t quite grasp it. Right around that time the first Hot Tuna record came out and I heard Jorma playing some of this stuff in a more accessible style to my skill as a guitar player. I tried to copy as much of what Jorma was doing at the time with that material and it just opened all of these doors for me. Years later I came back to Reverend Gary Davis stuff when I had the skill to sort of absorb it more in my own interpretation. Jorma has done that for countless guitar players, the way Reverend Gary Davis plays his stuff is not very linear it is more about feel than it is about actual execution, and Jorma managed to hold onto that feel but present it in a more structured way of execution. This inspired countless guitar players, and I’m certainly among them.

What is it like for you Teresa with Jorma?

TW: To start with I would take a tour with them just to hang on the bus with Jorma and Jack because they are cosmopolitan, and they also lived through and came out of that horrible ‘60s drugs and psychedelic whatever, and they are survivors shall we say, and just their worldly wisdom. Jorma went to high school in the Philippines and was well travelled because of his dad and his Finnish grandparents, so a very cosmopolitan dude. For me coming from the cotton patch it is just really cool hanging with Jorma and Jack. To stand in front of them and sing is like with the horns and that playing with Levon, what you do because of what is happening on the drums, Levon’s unique seminal drum playing, and Jack and Jorma behind you and the horn section in Levon’s band, it would just make me take a song and if I can keep out of my own way, I would be astonished at the places the song would go and my voice would go. Places I didn’t know were in me to go, and places I didn’t know the song wanted to go, all of this just inspired by them behind me. Jack knows he is driving the ship with that bass and will let you know too [laughs] verbally and physically [laughs]. It is a real trip, that is the only way to describe it, it is a real trip to just stand in front of them and sing [laughs]. If I can stay out of my own way, if I don’t think and just be there and let everything go for the ride it is magic on earth. It is why you do this to begin with, and if you just had more moments like that you could die and go to heaven today.

Don’t say that [laughs].

TW: [laughs] For a singer it is heaven on earth, and that is what they are doing behind you. I count a lot of things that are happening, big and little things that happen in an arrangement from playing with them that just happened on stage one night at a Ramble at The Barn, having Howard Johnson, I just can’t express it [laughs].

You haven’t done a bad job, Teresa. As far as your own career you have had two records released so what is next?

LC: Well, we have a live record that we did at Levon’s Barn.

TW: It is a really fun record.

LC: That was supposed to have been released last Spring, a good year ago but because we couldn’t go out and promote it we held off on it.

TW: Then there was the whole thing about ‘It Was the Music’ documentary.

LC: And that has its own soundtrack album to it, most of that is live too, so we didn’t want to be in competition, so most likely we are going to put this out sometime after the summer and we will figure out a promotional strategy for it. That is the next thing in the can, and it was great to be at that Barn again, and Teresa and I doing our stuff at the place we used to play with Levon every week. That joy is pretty well reflected on the record, I think. I am writing, I have got a few songs down and hopefully before the end of the year we will get in the studio and try and get another studio record done and just see what happens, you know. The record business is so nebulous right now, who knows, the thing is I have to keep writing because I have to keep writing, I don’t need it financially, I don’t need it to advance my career, I don’t need it for any other reason other than I am driven to do it. I am driven to do it to hear Teresa sing these songs and if they end up only being heard by her, me and her mother that is OK, so be it, but I still have to keep doing it.

That would be a shame though wouldn’t it [laughs]? In terms of your skills, you can do sessions, you can produce, you wouldn’t have to tour, so you have a choice of what you do.

TW: I have said why are we getting in a car and throwing our own gear in and out, a different town every night when you could be on a tour where somebody is loading your suitcases, and he is like I need to do this.

LC: I don’t want to be touring out on the road without Teresa, mind you if Paul McCartney calls me I may change my mind.

TW: This is a quandary for me right now. It feels conflicted in the moment because my dad is deep into Alzheimer’s, it is late stages Alzheimer’s, and my brother is in Florida holding down a serious job. In the documentary it is spelt out really clearly that I am torn between needing to be here in West Tennessee, wanting to be here full time, so I am trying to figure out how to do it. Larry wants to be on the road, and I enjoy being on the road to a certain extent, and I’ve been thinking about coming back to the UK since the pandemic, I just keep flashing on our last trip to the UK. There is a time for all things though, and it is almost like having a new-born, the situation we are in right now with my dad so that is a tough time to leave home with a new-born, and that is the best way I know of explaining it. I also want to hang with my parents while I have got them, it would be a very big thing for me and my heart is in Tennessee, I love New York and I miss New York, but it has been a blessing in disguise, though I hate that it took a pandemic to get me off the road, to be down here with them. It is a real blessing for me to be down here with them and just holed up in the house while we are all shut down.

There is an awful lot that is really bad about the pandemic, the deaths are horrendous for the friends and families of those who have died, but one of the upsides is that it has enabled people to recalibrate their lives and make sure they have set the right priorities. So, it is not all bad.

LC: That is right.

TW: Right.

LC: It gives you a new perspective, and you can either wallow in the depression of that or you can take advantage of the opportunities that it offers.

TW: Everyone has their own thing they have to wade through about this, it is different for everybody.

Finally, do you want to say anything to our UK readers?

TW: I just can’t wait to get over there.

LC: Britain is at the absolute root of what I do musically. Every time I have played over there with Bob Dylan, or with anyone else, it feels like we are going home in a sense, you know. Because there is a musicality in the British Isles that just wraps around me when I am over there. We will look forward to coming anytime we possibly can.