Louis Michot reveals himself to be more than simply a purveyor of Louisiana music.

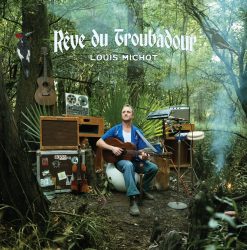

As a member of the Grammy award-winning Lost Bayou Ramblers and Michot’s Melody Makers singer-songwriter and fiddle player Louis Michot has released over twenty albums in his over twenty-year career that has seen him play his part in preserving and celebrating the culture and environment of Louisiana. It may seem surprising to some that his new solo album ‘Rêve du Troubadour’ is his debut as a solo artist and Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Louis Michot at home in Louisiana over Zoom to discuss why now is the time to release a solo album. Louis Michot shares his broader interests in music and explains the importance of different rhythms to the new songs, and why he thinks mixing world music can work so well. Niger musician Bombino is one of many artists making a guest appearance, and Louis Michot shares the happenstance that allowed this to happen. Louis Michot shares his concerns about the environmental issues facing Louisiana, which has the fastest disappearing landmass anywhere in the world today. All is not doom and gloom as he also shares his biologist father’s role in helping to remove the Ivory Billed Woodpecker from the extinction list.

How are you, and where are you?

I’m great and at home in Louisiana at the moment.

You are a very busy guy with your various cultural and music-related activities, why is now the time to release your first solo album, ‘Rêve du Troubadour’?

That’s a great question. I didn’t want to make a solo album, and being a busy artist one of the things that keep artists going is new projects and the ability to follow inspiration. I think one of the good things to come from the pandemic is to see in a clearer light the struggle musicians have because of touring to find time, and finances, to make new music. Since we were forced to take a break during the pandemic I had a lot of time on my hands, and not a lot of money, but I could use what I had to follow my creativity which was a nice change of pace from the last twenty years. The Lost Bayou Ramblers had just celebrated our 20th anniversary right before the pandemic, and it was the first time in a long time that I was able to sit down and just follow my inspiration., and what came from it was a selection of new songs that I didn’t know what to do with. I had a chat with my bandmates and they were like, this is Louis Michot music, it is not Lost Bayou Ramblers, this is not Michot’s Melody Makers. I was like man, here we go again, and two years later we have a new record and I’m touring with a new band, and it’s been quite an exhilarating process. So, I didn’t set out to make a solo record, but I’m really glad that I did.

That’s a great question. I didn’t want to make a solo album, and being a busy artist one of the things that keep artists going is new projects and the ability to follow inspiration. I think one of the good things to come from the pandemic is to see in a clearer light the struggle musicians have because of touring to find time, and finances, to make new music. Since we were forced to take a break during the pandemic I had a lot of time on my hands, and not a lot of money, but I could use what I had to follow my creativity which was a nice change of pace from the last twenty years. The Lost Bayou Ramblers had just celebrated our 20th anniversary right before the pandemic, and it was the first time in a long time that I was able to sit down and just follow my inspiration., and what came from it was a selection of new songs that I didn’t know what to do with. I had a chat with my bandmates and they were like, this is Louis Michot music, it is not Lost Bayou Ramblers, this is not Michot’s Melody Makers. I was like man, here we go again, and two years later we have a new record and I’m touring with a new band, and it’s been quite an exhilarating process. So, I didn’t set out to make a solo record, but I’m really glad that I did.

You are not just a songwriter so how do you manage your songwriting with your other activities, and is it your bandmates who decide who gets your songs?

I’m a band leader, I’m a musician, I have a label, I’m a father, I have all that but songwriting has been part of my life since I was a teenager. We don’t always have time, and I’ve written a bunch of songs for the Lost Bayou Ramblers, and one song, I think, for Michot’s Melody Makers, and these new songs were completely my babies. The way I write songs is that typically the inspiration hits me and hopefully I’m free enough to take it all in. For this process I was free, I had a lot of time on my hands. Sometimes I would wake up in the middle of the night or early in the morning, and I would go quickly to my studio houseboat and get it on record. At other times I would be taking a walk in the woods and the words would come to me, like ‘Boscoyo Fleaux’ and I would sit down and write them.

These songs were completely my creation, and I enlisted the support of my bandmates and guest artists, but it was all mine. I produced and engineered half, and Kirkland Middleton engineered the lion’s share of the second half, and it was all my writing. I would be like, no that’s not it, and in fact, on the first song ‘Amourette’, I did five different versions, completely different versions over a year and a half until I was happy with it. So I didn’t leave any stone unturned and I crossed every “T” to get it as I wanted it because this had my name on it. I thought if this has my name on it I’m making damn sure that I stand behind it, so it was a solo writing process, and I was lucky to have a bunch of great collaborators on the whole thing.

While you are a cultural ambassador for Louisiana the music and guests on the album are quite varied. How did that come about?

It was everywhere from who is the best zydeco drummer, I know because I had one zydeco song, and I played accordion, and Corey Ledet is one of my favourite zydeco drummers, though he is known as an accordion player. Leyla McCalla was the last one on the record because I wanted her to join Bombino on ‘La Cas de Marguerite’ on the vocals, but she was so busy but we managed to squeeze her in on the end. She and I talk about life very often, but we very rarely talk about music. I left that solo section open and I said to myself I would love to get Bambino over but that will never happen because he is in Niger. A month later there was his tour schedule and he’s playing New Orleans and Lafayette. I rang up one of his bandmates and we worked it out and he came to stay for a few days, so that was a dream come true. Quintron, it was his magic touch that gave that fifth take of that song, Amourette’, the life I wanted it to have. It was just a very basic beat he made, but it was exactly what I needed. String Noise really puts the cherry on top of ‘Souvenir de Porto Rico’. Dickie Landry lives just right down the street, and I was like there needs to be one more element to Boscoyo Fleaux’ and I rang him and he just jumped in his car and came down and we recorded it in this very room. It was a very natural process all the way around, it was like who would I like to fill that, and then, voila.

There is quite a bit of a world music flavour to the album. How important are the various rhythms to the music?

That’s another great question. Coming from a traditional background we have a few rhythms in Cajun and Creole music. We have the two-step, the waltz, and the blues, and now that you ask about it I think I hit one two-stop and one waltz, and the rest of it is new rhythms from what people expect from me, but they are the rhythms that I like. It is the rhythms of the music that I listen to and you can hear the rhythms of different influences and I like everything. I didn’t limit my songwriting to the traditional structures, and a lot of the rhythms I made myself like on ‘Boscoyo Fleaux’ and ‘Chanquallier’. On ‘La Cas de Marguerite’ the rhythm comes from a sample that my dad took in 1989 at a festival in France of an African band from Morocco. I took his cassette tape, and I always loved his recordings, I sampled them and laid them over to make the beat of ‘La Cas de Marguerite’. There are all kinds of rhythms in the album, and some of them don’t have much rhythm element as such but they have their own rhythm such as ‘Les Beaux Jours’ and ‘Souvenir de Porto Rico’.

You are a musicologist, do you have a view of why various Kinds of world music seem to mix so well?

Another great question. I’ve loved music from all around the world for years, even the different music of America and Louisiana, and one of my most fulfilling experiences as a musician has been the ability to collaborate with musicians internationally, whether it’s us travelling to another country, or musicians travelling to us here in America. I play with forró musicians from Brazil, I play with mariachi musicians from Mexico, Tuvan throat singers, and on and on. All these experiences have been something amazing because in one sense you are taking something that is often a completely different language and a different set of instruments and rhythms, and somehow they work so cohesively together and the results are always greater than the sum of its parts in these experiences. I’ve been influenced by that so much over the years that I didn’t even think twice about allowing those influences that came to me to make their way to this record.

We spoke to Corey Ledet recently about his mission to keep the Kouri-Vini language alive. What do you think of that?

I think it is brilliant, I think it is completely necessary for him as an artist personally and for the culture as a whole. It takes people to take an extreme step like that, making an entire album in Kouri-Vini because he not only learnt a lot in the process but he is continuing the language by teaching others and giving people a tangible example of Kouri-Vini so they can tap into it. It takes a bunch of little things like that to keep a language going. I’ve heard Kouri-Vini around me all my life but it is very rare that you hear it spoken enough so you can grasp onto it, even for him and his family speak it. So, I think it is a really big step in his journey as an artist.

What’s your view on the difference between Cajun and Creole music?

That’s an interesting question because I think it has changed over the decades and generations. It is interesting because at one point people were telling anyone of European descent who spoke French that they were Acadian and Cajun, even if they didn’t have any blood coming from Acadie. You had people from like Evangeline Parish who don’t have any Acadian being called Cajun because they are of European descent. If you are African or mixed then they think you are Creole, but that’s more of a new take and think it’s not correct because Creole in essence was anyone born in the New World. When my father’s band Les Freres Michot started playing Cajun music as Michots, and Michot is a Creole French name, their grandma said, “You have the nerve to call yallselves a Cajun band, we are Creole”. We are of 100% European descent, we don’t have any African or Native American heritage. So, to her Creole is one thing, to another, Creole is another thing, and that’s the whole thing about the word Creole, there’s the Creole tomato, the Creole pony, Creole French. When the word Cajun came in all of a sudden it became racialised where if you are white European and speak French you are Cajun, and if you are mixed or anything else you are Creole. It became a separation when really, it is much more complex and diverse than that, and we need to focus on our similarities and connections rather than our differences.

What’s your view of Louisiana today with its economic, environmental and political challenges?

You are absolutely right. For one we are the fastest disappearing landmass on Earth, and it’s been that way for quite some time now due to erosion. We are one of the top producers and exporters of oil and gas which hasn’t helped the environmental quality of the State. It was supposed to have helped the economic quality of the State but it hasn’t really because that money was supposed to go into things like education but it hasn’t and we are still 49th in the Nation, 49th out of 50. It is one of the most extreme States, it is the belly of the beast really. We definitely felt the politics and racial tensions of the 2020 election, and ‘Acadiana Cultural Backstep’, which is number nine on the record, is about what happened here locally. What I was trying to say with that song was that on the one hand, our politicians will raise up the culture thing, and on the other, they will minimise the funding to those communities that are essential to that culture, namely the African American communities, the Creole communities. There was a big issue here in 2020 when our local government here in Acadiana was defunding the parks in the Black side of town, and putting all funding to the new parks in the south side of town. That’s what I wrote in that song, you put culture on a t-shirt and on your political campaigns, but you cabal with the racists and you are going with this new American movement which is causing a lot of controversy, and they are even throwing red hats off the stage if you will, red and white hats.

Any plans to bring the new album to the UK and Europe?

I would love to come and I know it has gotten harder for bands to make it to Europe because the arts don’t seem to have more money, especially to keep up with inflation, and it costs so much more to travel and the guarantees have remained the same, so it has gotten harder and harder to make it work. Corey Ledet and I are joining Leyla McCalla in Paris on February 10th, and that’s the only thing lined up on that side of the pond. I’d love to come back and we are trying to pull some strings and make things work, but as I say, it takes quite a few heavy anchors to make it work.

We like to share new music with our readers, so currently, what are your top three tracks, artists or albums on your playlist?

This is on my deck right now, it is ‘Claudette & Ti Pierre’, they are a Haitian duo and he plays a 70s-type organ with built-in beats and she’s a singer. It is really good stuff, and their Creole is similar to our Creole but pretty different and I can understand a lot of it. I found it at the local record store, and I was like I’m gonna check that out. From Lyon, France, Le Peuple de I’Herbe’s ‘Tilt’ who are kind of a Beastie Boys band. And a little bit of Cookie and the Cupcakes, and why not? Finally, I’m still trying to find out more about Lois Moreau Gottschalk who wrote ‘Souvenir de Porto Rico’ on my album. That has been very interesting because he was the one who, through him writing music, was able to record the new music of the New World where people of all nationalities were coming together. Things like ‘Bamboula’ which is Congo Square, and it’s very interesting to see how he synthesised what he was hearing into his piano. He would give these monster concerts with hundreds, and even a thousand, musicians. So that’s been an interesting learning curve.

Is there anything you want to say to Americana UK readers?

I’m just so excited to be able to bring this music out that I didn’t realise I had in me, and I was also able to bring it to life and it is done by the support of listeners who also want something fresh. So, that’s why I did it. I also want to mention that the Ivory Billed Woodpecker makes an appearance on ‘Boscoyo Fleaux’, the sample from 1935. My dad, who is an accordion player, is also a PhD Biologist and he’s been looking for the Ivory Billed Woodpecker since the 1970s using the same recording I sampled. They have finally released their research this year which has helped keep the Ivory Billed Woodpecker off the extinction list. I kind of liken the Ivory Billed Woodpecker to Louisiana French in that you know it’s there, and you can go looking for it but it is really hard to find. The culture is like that, It is there, but sometimes it goes into hiding to protect itself, but hopefully, as we protect it, it can become more mainstream. It is there in the dark places that nobody thinks to look. It is not something you can find on a t-shirt or in a store, it’s like you very rarely find a real Gumbo in a restaurant, you’ve got to get inside and immerse yourself, and then finally it will make its presence known to you.

I’m just so excited to be able to bring this music out that I didn’t realise I had in me, and I was also able to bring it to life and it is done by the support of listeners who also want something fresh. So, that’s why I did it. I also want to mention that the Ivory Billed Woodpecker makes an appearance on ‘Boscoyo Fleaux’, the sample from 1935. My dad, who is an accordion player, is also a PhD Biologist and he’s been looking for the Ivory Billed Woodpecker since the 1970s using the same recording I sampled. They have finally released their research this year which has helped keep the Ivory Billed Woodpecker off the extinction list. I kind of liken the Ivory Billed Woodpecker to Louisiana French in that you know it’s there, and you can go looking for it but it is really hard to find. The culture is like that, It is there, but sometimes it goes into hiding to protect itself, but hopefully, as we protect it, it can become more mainstream. It is there in the dark places that nobody thinks to look. It is not something you can find on a t-shirt or in a store, it’s like you very rarely find a real Gumbo in a restaurant, you’ve got to get inside and immerse yourself, and then finally it will make its presence known to you.