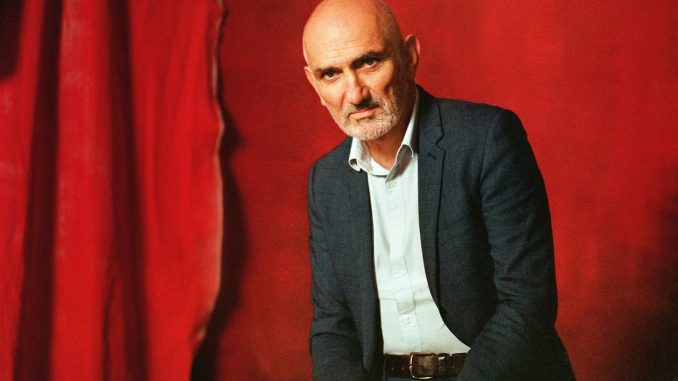

Paul Kelly is a big deal in Australia – his latest record went straight to number one and he supported Bob Dylan on his 2011 Aussie tour, although he still remains one of his country’s best-kept secrets for UK audiences. (But everyone knows what Neighbours is. Oh the injustice). The new album “Life is Fine” is a collection alive with energy and good humour, described by The Guardian as containing some of his “best songs in years”. Mark Whitfield caught up with him at the start of the UK leg of his current tour and chatted about how the new record came about, writing songs from poetry and why nobody does Hank Williams songs like Hank Williams.

The new album has been described as being evocative of some of your big records from the 80s like “Gossip” and “Under the Sun” – did you intentionally try to recreate that sound?

It wasn’t intentional but I was aware of it as it was happening. Some of the records I’ve recorded over the last few years have been a bit more off the beaten track. Last year for instance we did a record of Shakespeare sonnets and then a record of songs I’d sung at funerals, and before that the “Merri Soul Sessions” which had six different singers singing my songs, and before that more of a pastoral song cycle record called “Spring and Fall”, so I hadn’t really done an upbeat band record for a while. So I was pretty keen to do that, and make a playful, upbeat full-band record with lots of harmonies, and it’s not surprising it sounds like some of the old records.

There are quite a few similarities between them in term of the bands. Everyone in the band has got quite a wide range of influences which means we can sort of throw songs around and tackle them in different ways, so the record has a lot of variety in it. Ash Naylor who plays guitar reminds me a lot of Steve Connolly from the Messengers, they are both influenced by similar kinds of things – they’re not really busy classic guitar players, they like to make up simple but memorable parts without too many notes, so yeah once we started making the record I thought “oh yeah that sounds quite a bit like the older records”. The one that stands out is Firewood and Candles – it sounds like it could be something from thirty years ago, so it’s funny how these things come around sometimes.

It seems to be more diverse in styles too, kind of like it’s moved away from some of the folk underpinnings of some of your more recent records – does that reflect a change in your taste or did you just want to try something new?

I think the songs were all quite different to each other and I always like to record each song in its own little world. I’m not worried about trying to make things sound coherent because if you have the same band and the same singer generally it will just have its own thread. And also I picked songs that, even though they’re diverse, there are certain links between them. I mean to me this record is more light-hearted, there’s more comedy in the songs than in say the last few records: My Man’s Got a Cold, Leah: The Sequel, Josephina and Firewood and Candles. I was conscious that every time I wrote a song that was leaning more to the humorous side of things, I put them aside for this record.

Yeah it does feel like a much happier album than some of your more recent albums which is almost counter-intuitive as the world seems like it’s in such a dark place at the moment. Did you record it without wanting to touch heavily on some of the grimness around?

It’s at the back of my mind but it’s sort of hard to talk about intentions with records as songs always just come at me sideways or haphazardly. It’s not like I wrote them all in the last year or I wrote a group of songs that reflect a certain state of mind or my thoughts and feelings on last year, I just don’t write like that. They come quite randomly. When songs come up I sort them, into little piles or little drawers. It was more of a musical thing – I wanted the album to be mainly upbeat and I did want a more upbeat mood, and that was also at the back of my mind, it’s easier to wail and moan about the state of the world but sometimes you just have to go for the joy.

It’s dark and light in a way, things always get mixed up for me. Even the songs with comedy have darkness as well, typified by the title track Life is Fine which is based on a poem by Langston Hughes, and it’s a poem about suicide, but it’s funny. The narrator of the song is thinking about suicide and in the end he decides not to kill himself, so the song ends with a burst of joy, you know, life is fine, so for me that’s the perfect coda to the feeling of the record.

You used Vika and Linda Bull on this album which works really well. Is that something you feel like you might explore more in the future, with different vocalists?

Yeah I don’t know why I didn’t think of this 30 years ago (laughs). A lot of my favourite bands always had someone else besides them singing the main songs – the Rolling Stones, the Triffids, the Velvet Underground… there’s always someone else pops up singing a song, and the good thing is that I thought well this is a band record, so it sort of makes sense to have Vika and Linda do a song each. They’re really strong lead singers as well as being great harmony singers. I guess what planted the seed for me with that was doing that record the Merri Soul Sessions where I had different people singing my songs and I remember thinking oh yeah I should do this more, it’s obvious, why didn’t I do this before? I’m a bit slow sometimes! (laughs) Even if you really love a particular singer, on a record it’s good to have a little break from that singer.

What made you decide to record “Don’t Explain” in the studio finally? Have you got any other re-recordings stashed away?

I don’t know, I sort of have to trawl back. Don’t Explain I used to play occasionally live but I never recorded it in a studio. There is a live recording from back in 1992 and I think I’d just written it then so played it, and I’d been trying to get different people to sing it over the years, I’d passed it on to people I knew but it never sort of got picked up. But then when I was doing the new record, I had a song for Vika and was looking for a song for Linda and I just thought ah maybe we should try Don’t Explain, and that was good because that was one that got pretty much transformed by the band in a way I hadn’t imagined. They’ve taken it to a kind of Fleetwood Mac kind of place (laughs).

One of my favourite tracks on the album is “Letter in the Rain” which sounds like a lost country classic – could you tell me a bit more about that song?

It was the last one we did in the session. I had the tune for a while and I had the title, I knew how it would go – “letter in the rain” would be the last line of each verse but I just didn’t know what the story was to get there, but I liked the tune and thought I’d love to get this one in on the record. So you know there’s nothing like having a deadline, I finished it while we were doing the recording and I played it to the band. And you can always tell when you play a song to the band, they generally like them and get stuck into them but Letter in the Rain, I played it to them, and they just got it, like we did it on first or second take. Songs like that are a gift. They don’t happen very often.

You use literature, both prose and poetry, as a reference point for a lot of your tracks. As you mention, the lyrics for the title track were written by the US poet Langston Hughes, and obviously Raymond Carver gave you the title for “So Much Water So Close to Home”. How important to you using literature in music?

For me it’s very important. As a songwriter it’s important you keep your ears open. Songs come from anywhere, the things you hear people say, or things you read, and a lot of my songs come from something I’ve read. There are lines in my songs that come from other songs, that come from poems, they come from folk songs or things I read in books. They come from everywhere, but it has been more so over the last five years that I’ve consciously put poems to music. I thought for a long time that I couldn’t write songs like that. I’d always started writing songs with the music first and then gradually getting the words to attach to it, and for some reason I thought if you had the words first, it’d be too restrictive for the music, it would put it on too rigid a rail. I’d never write my own words first, my words would come with the music, so of course I never thought to use someone else’s words because of that same principle.

But about five years ago I got involved with a project of putting poems to music, recorded with an orchestra and classical composer, and that sort of opened a little door for me and I realised I was completely wrong, in the same way as I was wrong about not having other singers on my records 30 years ago (laughs). So it’s good to learn new things as you get older. So after this project which was called “Conversations with Ghosts”, we did a live recording of that, I just got into the habit of putting poems to music just for fun, and that’s what indirectly led to the Shakespeare record, it wasn’t actually restrictive at all. That was a great discovery for me as for me words are the hardest part of writing songs so to have these beautiful words to start with – over half the work is done for writing the song.

So apart from Shakespeare, I put poems to music just for fun. I’ve done a couple of Gerard Manley Hopkins poems, and of course it bled into this record too with the Langston Hughes poem which when you read it on the page actually reads like a song lyric, I didn’t have to adapt anything – the lyrics in the song are exactly the same in the poem, it falls naturally into verses and choruses. It’s like having another arrow in the quiver, another way to write songs which is a good thing for any writer to be able to find new ways, because really every writer falls into their own habits and patterns. I guess you’re always trying to find a way to break out of that.

Life is Fine

Langston Hughes, 1902 – 1967I went down to the river,

I set down on the bank.

I tried to think but couldn’t,

So I jumped in and sank.I came up once and hollered!

I came up twice and cried!

If that water hadn’t a-been so cold

I might’ve sunk and died.But it was Cold in that water! It was cold!

I took the elevator

Sixteen floors above the ground.

I thought about my baby

And thought I would jump down.I stood there and I hollered!

I stood there and I cried!

If it hadn’t a-been so high

I might’ve jumped and died.But it was High up there! It was high!

So since I’m still here livin’,

I guess I will live on.

I could’ve died for love—

But for livin’ I was bornThough you may hear me holler,

And you may see me cry—

I’ll be dogged, sweet baby,

If you gonna see me die.Life is fine! Fine as wine! Life is fine!

I read that you listened to a lot of people who’d be considered americana icons when you first started playing guitar, Gram Parsons and Neil Young for instance. Is that music still something you feel influenced by these days?

Gram and Neil yeah, and Hank, Hank Williams. Early Bob Dylan too, songs from his first couple of records. But Hank Williams has always been a kind of touchstone I always come back to. The interesting thing about Hank is that his words are nearly always so mournful and bitter, but you listen to the band playing and the tunes, and there’s always a cheerfulness to it. I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry is probably the saddest song ever written, and I’ve heard many many versions of that song, and everyone does it slower than Hank. You go back to Hank Williams’ version of that song, with the band, and there’s a real pep in their step and that’s the clue, that’s the key to it. He never wallows in the misery, he’s singing and his voice is full of pain, but the band is creating this other world around it, so there’s this joy and pain mixed together. So that’s a real test for me as a songwriter to keep that in mind. Again, it’s the dark and light.

“Life is Fine” is out now on Cooking Vinyl. He plays the Rescue Rooms in Nottingham tonight, Shepherds Bush Empire on Saturday and then heads to Europe for more dates.