Songs are like places that you can visit and inhabit for a few minutes.

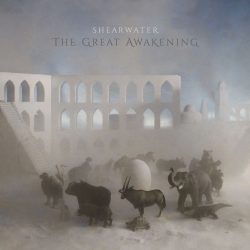

Regular visitors to Americana UK know that the music featured ranges across the widest spectrum of what can be considered americana, and is not limited simply to what could be viewed as traditional americana, and while hats, boots, and checked shirts are fine, they are not the sole criteria for coverage. There is little evidence of hats, checked shirts, and boots in the wardrobes of members of Shearwater which started out as a side project for Austin indie rock band Okkervil River’s Will Sheff and Jonathan Meiburg. Shearwater become Meiburg’s main vehicle when he left Okkervil River and Sheff left Shearwater, and Shearwater has had a revolving group of musicians ever since and their music reflects Meiburg’s interest in the natural world and his approach to melodic songs and sounds. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Jonathan Meiburg in Hamburg, Germany, to discuss Shearwater’s new album ‘The Great Awakening’. Meiburg also explains that he believes songs are like places that you can inhabit for a few minutes, and how he is now being drawn much more to sound and texture and how this means ‘The Great Awakening’ is meant to be experienced as much as listened to. He also shares an insight into the recording of Roky Erickson’s last record, ‘True Love Cast Out All Evil’. Finally, if you want to know what a Xenarthran is, read on.

How are you and what are you doing in Germany, playing a short tour?

I’m fine, and yes I’m in Hamburg because my partner took a job at the Natural History Museum, she studies marine worms and they had a job for a Curator of Annelids, which are essentially worms, and I can tell you there aren’t many jobs like that in the world. She took the job and I’m portable, so I came along. The pandemic stopped touring for two years so now everything is so backed up booking tours is really difficult so I think it will be some time before we are performing again.

Apart from a once in a hundred year pandemic, why has it taken 6 years to release a new Shearwater record?

After the last record, I really felt burnt out, and I wanted to do something completely different. Luckily I had several projects that occupied my attention, including Loma which I formed with my friends Emily Cross and Dan Duszynski of the band Cross Record, and we made two records for Sub Pop Records, which were very different from the last Shearwater records. With the first one, I basically wanted to make something that was the opposite of ‘Jet Plane and Oxbow’, where the instrumentation is very acoustic and dogs walk by the microphone and bark in the middle of songs, a very, very hairy woolly recording. We also released our Quarantine Music 1 – VIII online, and all of that took some time, but I must admit to being a bit surprised when I realised it was six years since the last Shearwater record.

Are Shearwater still a band or is it more a Jonathan Meiburg vehicle?

It has become that over time because it is very hard to keep a band going for twenty years, and I can’t quit because once I do it will be over, haha. I have the consolation of having a group of people I can work with, some of whom I’ve worked with for many years and some of whom come and go, and during the pandemic we could hardly get people in the same room. It was fortunate I happened to be in Texas right next door to my friend’s studio, so we could work together, but at this point, I am the last man standing.

With your songwriting, how do you decide what is a Shearwater song, and what may be more suitable for another project?

For me, songs always start from a sound and a feeling, and if I feel that the idea as it is developing is it is going to be right for my voice I will start singing it, and I will start playing with it for a number of weeks very casually. If it stays with me, and something about it makes me feel something, then I keep developing it. Over the years I’ve learnt that one of the things you can do with a record is to not work on it, in the sense that it is good to dive in and work on it for a couple of weeks and then not think about it at all and just leave it and then come back and work on it for another couple of weeks because you tend to notice the things that are real problems, or that are really successful, rather than being lost in the weeds. That is especially true making a record like ‘The Great Awakening’ which is so textual and carefully balanced.

Did you select the songs for ‘The Great Awakening’?

For this record, yes, I chose the songs. For Luma it is completely different, it is a democracy so I don’t get my way all of the time. It is a triumvirate, which is a really interesting structure for making decisions because it is two against one every time, haha. With Shearwater it ultimately comes down to what I want to do, but there is a lot of input from Dan Duszynski, my co-producer, and Emily Lee, so in the final stages of the record the three of us were really the core group who made decisions on what stayed, and what went out, when a vocal was good enough, that sort of thing.

Is ‘The Great Awakening’ a pandemic record?

Yes, I was living in Dripping Springs, Texas, which is about forty-five minutes from Austin for almost the entire time, and except for trips to the grocery store, I never saw more than three or four people for a very long time. Luckily there was a lot of brush clearing to be done on the property where the studio is, so I was able to get out of my trailer and just cut down juniper trees for hours and hours every day. It is a lot of fun, and a good way to get out of just worrying whether civilisation was collapsing or getting too fixated on the sound of a hi-hat, or some other recording minutia.

How many people were in the room when you were recording?

Usually, it was me and Dan, the engineer, and we brought people in to play. Josh Halpern, the drummer on ‘Jet Plane and Oxbow’, came in for one day I think, and we had him lay down some drum tracks. We had him play some tracks that didn’t have a song, we said can you play a pattern like this, and we took all of that and reorganised it. There were some songs that were fairly straightforward performances from his perspective, but by the time they appeared on the record they were very different. The same is true of the strings, all the strings were performed by one person who I had never met, which is fascinating. Emily Lee made the arrangements, and we sent them to our friend Theo Karon, who was working in Los Angeles at the time in his studio, and he had a colleague Dina Maccabee who played violin and viola, and she brought in several instruments and they multitracked and then sent the strings back to us. It was very different from any other record I have worked on, I was surprised at just how malleable everything could be. Just because you had recorded the strings for one track didn’t mean the strings had to end up with that song, it made us freer in the way we could use the material we had recorded, we could move them around to different songs or change the pitch with the speed. We were able to work with the clay a lot longer before we fired it.

Usually, it was me and Dan, the engineer, and we brought people in to play. Josh Halpern, the drummer on ‘Jet Plane and Oxbow’, came in for one day I think, and we had him lay down some drum tracks. We had him play some tracks that didn’t have a song, we said can you play a pattern like this, and we took all of that and reorganised it. There were some songs that were fairly straightforward performances from his perspective, but by the time they appeared on the record they were very different. The same is true of the strings, all the strings were performed by one person who I had never met, which is fascinating. Emily Lee made the arrangements, and we sent them to our friend Theo Karon, who was working in Los Angeles at the time in his studio, and he had a colleague Dina Maccabee who played violin and viola, and she brought in several instruments and they multitracked and then sent the strings back to us. It was very different from any other record I have worked on, I was surprised at just how malleable everything could be. Just because you had recorded the strings for one track didn’t mean the strings had to end up with that song, it made us freer in the way we could use the material we had recorded, we could move them around to different songs or change the pitch with the speed. We were able to work with the clay a lot longer before we fired it.

How did you imagine the record, were the individual songs the important part or was it the overall sound?

I always think of a record as a giant dark room and I’ve got a torch and I don’t know what the dimensions are. So you begin by just trying to find out its contours and how you might shape it. It was the same with the book actually, you don’t know what your book is about until you’ve nearly finished it, and you don’t quite know what your record is until it is nearly done. But that said, I think I’m not alone, especially as musicians who stay in the game and keep making music seem to gravitate toward becoming more interested in sound itself in a very pure sense, and I’m probably more excited by sound and textures now than I have ever had been. So we spent a long time exploring and developing them, and we even made eight instrumental records while we made this record so we could just explore different kinds of sound outside of having a formal song structure. We put those on our Bandcamp page under the title ‘Quarantine Music’ and they are meant to be listened to or not, you can have them as background in the ambient vein. It was like a way of experimenting with colour before actually trying to paint a distinct image with it.

When you are sculpting your sound, how do you know when it is right, how do you know it is finished?

Because it makes you feel something, when there is a reaction, that is the most important thing. There were songs we worked on for quite a long time and when we were finished if we didn’t feel anything from them we just threw them away. In the end, it had to come down to that. Sometimes when you are working on a song you do feel something from it, and then you work on it a bit longer and that stops happening and it is like, wait a minute should we go back a few steps and stop whatever road we are on because we are starting to ruin it, whatever it is. There was one on song the record called ‘Milkweed’ where we just kept cutting elements out of it, we just kept cutting and cutting it, cutting vocal lines, cutting lyrics, and it almost became a game to see how far we could go to see if there was even a song there at all. The more that we cut out of it the more I liked it and the final form it is in is quite minimal, but it also changes very subtly. I’m really proud of that one, not that we will see it in the charts anytime soon, haha. As an experience, I think we arrived somewhere very special with that song.

How important was Dan Duszynski to ‘The Great Awakening’?

If I had made this record all by myself it would have been completely different, and nowhere near as good. Dan says that creating and analysing are two very different energies, and he is good at indulging both. He will let almost any idea past the gates at the start and then when it is time, he will switch to analysing them saying this works, this doesn’t. He is very open and very selective, which is a very important combination and also very rare. He is also very humble, so much so when we were making the first Loma record he let me play nearly all the drums on the record, without telling me he himself is a very good drummer, and I’m not, haha. It is rare to have that combination of humility and imagination, both with instruments and in the recording realm. Luckily, because it was the pandemic and we were stuck in this house, and we had Crowdfunded the record so we had a good budget going in, and we used that to make the studio as good as we could make it. There are difficult things about that time, but in some ways I was operating with fewer constraints than I ever have for a record.

You are working with Secretly Distribution on this record, what are they like?

It is funny, I knew them from when I was with the band Okkervil River, which is now back in the 19th Century, haha. Interestingly I have heard that kids refer to the 20th Century as the 1900s. When I first met the people involved with Secretly, it was two record labels Secretly Canadian and Jagjaguwar run out of an auto parts store in Bloomington, Indiana, and it was a very small operation. They have grown by leaps and bounds over the years, and when I approached them about working on this record they had become this juggernaut of an organisation, but it was also a return to working with people I had worked with a long time ago.

You appeared with Okkervil River on the Roky Erickson’s ‘True Love Cast Out All Evil’, what was that like?

I just went in and did some overdubs on that but I didn’t work with Roky at all, though I talked to Will Self a lot while he was producing that record. Roky’s performances had to be compiled fastidiously and carefully, he would do a vocal through for a song and there would be a few lines that were absolutely brilliant, and then there were others when he seemed just lost. It was a lot of work to try and sculpt those performances. I remember Will being very preoccupied with the demos of Roky he had to work with at the time. For my part, I played some guitar and some piano, I wasn’t close to the centre of that record, but when I heard the final product I was really pleased. There are some beautiful moments on that record, ‘Be and Bring Me Home’ is a really beautiful song, just an incredible song.

Who are your core musical influences, the ones that made you want to become a musician?

My mother’s family was musical, her sister teaches opera now in college, my grandfather played ragtime piano in the key of F. He was self-taught so all his songs are in the same key, haha, and my mother taught piano a little bit. So they all influenced me at home growing up, my mother also said I would put on a record because of its cover, which was very colourful, and it was E Power Briggs playing Bach. I would set up pots and pans on the floor and play imaginary drums, and my mother said it was really horrible but that I did play in time, haha. My fate was sealed from an early age I think. Growing up I was also in a choir and in bands at school and at church, and that was all just a normal part of my life. The church part of it is something that is a blessing and a curse because learning choral technique shows you how to use your voice in a certain way, but I’m still trying to stamp the choirboy out of my voice forty years on, haha, or embrace it in other ways. This is one of the things that is so wonderful about Scott Walker, he has a beautiful operatic-type voice, it then bends and twists in wonderful ways.

You feature armadillos on ‘The Great Awakening’, why are you attracted to them?

The album reflects in an oblique way my interest in the living world outside music, which has always been an interest for me. ‘Jet Plane and Oxbow’ was such a human-focused record, I was really getting fixated on the human world, and writing the book, ‘A Most Remarkable Creature’, reminded me that people are important but are only one among many in the history of life on Earth. When you try and take that view of what it means to be alive it is very calming, and fascinating, so full of mystery and wonder. Sometimes it can be tender, it can be pitiless, but it is always different from what we receive every day from the internet which is just about people. So I wanted to make a record that for me sounded more hopeful than the previous one, but the hope for me is not found in the human world so much as in the larger world of which we are part.

The song ‘Xenarthran’ is about a group of mammals that are living representatives of sloths, anteaters, and armadillos, and they are from South America as I learned. There were and are a number of different species of armadillos, including some that were huge, similar to the giant ground sloths that were bigger than bears. But today there is only one little Xenarthran who has walked up from South America and established a foothold in North America and remained and that is the nine-banded armadillo that we see often in Texas usually at dusk. I loved their persistence in that they trundled all this way to a completely new land, because North and South America were separated for so long, and armadillos are so different from every other animal in North America. They have just doggedly kept on moving, seeing what this place had to offer them. I find them very inspiring, and that was the working title of that song and I just let it stick. A little of it was sheer perversity because I loved releasing a title that nobody could pronounce, including me, haha.

At AUK, we like to share music with our readers, so can you share which artists, albums, or tracks are currently top three on your personal playlist?

Something I’ve kept returning to recently is ‘What’s Going On’ by Marvin Gaye, it is so stunning and so strange and immediately engaging. No other record sounds like it, it just creates its own world, and at the same time these great Motown musicians are just killing it in the studio, the string parts sound like they are in his imagination, and then there are multiple Marvin Gayes, all singing at the same time on different lines. I just never get tired of listening to that record, there is always something new to discover in it and that is the kind of record I aspire to make one day. Laurie Anderson ‘Mister Heartbreak’ is another one I recently listened to. The Ethiopian pianist Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou’s ‘Ethiopiques 21: Ethiopia Song’, she was raised in Switzerland but then went back to Ethiopia. Her style of music is fascinating and very distinctive, it has a Europeanness and not just an Africaness but an Ethiopianess. The pieces are all written by her, and they often meander and seem improvised except some of them will suddenly snap into focus. There is no music quite like it and I never get tired of it and I can listen to it over and over again, and I have. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

Finally, do you want to say anything to our UK readers?

The term americana always makes me smile a little bit, it is one of those terms I struggle to define. For a while there it seemed that any band who had a pedal steel was americana, and I’m not sure how Shearwater fits into that realm. Until a few months ago I had lived in America all my life, but one thing working on the book taught me was how little I knew about the continent where I have lived all my life, what the story of life there was, and how different North and South America are from one another, and how they have influenced one another. What interests me about the United States is that the more I learn about it, the less I understand it.

That is certainly true at the moment.

I think americana has been a fantasy of what it is, but then you can have an indulgence of that fantasy, the Western tropes, the cowboy stuff, country music, whatever that means. But then you could also say americana is a music that is trying to find out what is going on, which would be a far more varied and frightening, and inspiring, genre. Part of the problem is that the United States is not a very self-reflective place, it is overdue.

Something is going to have to happen because everything is just log-jammed at the moment.

It is, and it is a very weird thing to watch your country go insane, mind you wouldn’t know anything about that would you, haha? At times of great stress and tension, it means there is grist for the artistic mill, but for the sake of everyone who lives there, I wish the United States was a bit more boring.

Finally, I just want to say that this record is conceived as an experience that you walk into and sort of float through it, and my favourite albums have the quality of feeling like they are listening to you and there is room for you in them. At this point I’ve heard it so much I don’t know whether it does that or not, but it certainly was the aim. You have to think of songs as places, a song is a place you inhabit for a few minutes of your life, and with this record, I think we have got closer to that goal than I ever have.