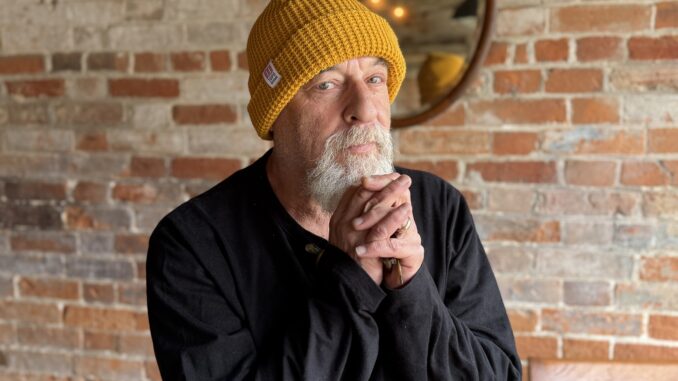

Jerry Joseph recently released “Panther Tracks, Vol. 1”, a raw, unflinching collection of songs that reflect his life, struggles, and triumphs. During Joseph’s recent UK tour, AUK’s Andrew Frolish spent some fascinating time with him over Sunday lunch in a pub in Easton, Suffolk, where Jerry tried toad-in-the-hole for the first time and was delighted by the concept. He was frank and open, personal and intimate, chatting about everything from the time he was dating a supermodel and ended up hugging Harrison Ford, to his friendship with Woody Harrelson, his songwriting trips to Mexico, encounters with guns, drugs, and cartels, his near-death experiences, family and his reflections on spirituality, AA and the 12 steps. Joseph spoke candidly about Portland life, the challenges of ageing, the impact of AI on music, and the freedom he finds in creating. After those personal tales over toad-in-the-hole, we had the opportunity for a more formal interview, to explore the recent album, the musicians he has collaborated with over the years, and the spiritual connection with his fans created during his live shows. The interview was bookended by Jerry’s gig at The Hope and Anchor in London and his show at the John Peel Centre in Stowmarket. As ever, the emotional intensity of his performances were infectious and captivating. Outstanding pedal steel player Henry Senior shared the stage with him in London. At both shows, Joseph was joined by the talented singer-songwriter Ella Spencer and Stretch, an Australian accordion and washboard player. Remarkably, Jerry and Stretch had only become acquainted about three hours before the London show, and yet they played together with such precision and style that it seemed they had been rehearsing for weeks. This kind of spontaneity and musical freedom is typical of Jerry Joseph, who played both evenings with joy and warmth, alongside the familiar fierce on-stage presence, channelling something bigger, something beyond.

Besides his reflections and recollections, Jerry shared photos of far-flung places from his personal collection, some of which can be found below. His vast experience of the world, gained through travel to such places as Iraq, India, Mexico, Afghanistan, Nicaragua, Brazil, and Japan, ensures that he is fascinating company.

Andrew: Jerry, tell me about “Panther Tracks, Vol. 1”. How did this record come together, and what was it like working with The Jackmormons again?

Jerry: Usually, my main income is live – doing shows. Only in England do I pay to do shows! But there’s a pretty solid fan base, particularly certain markets. So, The Jackmormons are always in my life. We rehearse in The Panther, the studio owned by our drummer, Dex (Steve Drizos). One of them always shows up when I’m doing something solo. COVID had started, and my bass player, Stevie James’s wife, had to get a new heart. I’m one of those people that people know if they call me, I’ll put things aside and jump into fundraising and call in every favour I can. We played something, and it made a lot through donations. My drummer, Dex, is married to Jenny from The Decemberists – they were already COVID-exposed, and we had played together the night before everything shut down. We were in San Francisco, and it was funny because it was packed but had that ‘end-of-the-world’ vibe. Anyway, the three of us – Dex, Jenny and me – started playing together every Thursday night at 6 o’clock and you could watch online. We’d rehearse, play a cover or two in The Panther. It made a lot of money for us, like $5,000 or $6,000 a week. It meant that I could pay the studio and the musicians, and it just kept fucking going! We did 64 weeks in a row. Then, Stevie joined us, so it was actually The Jackmormons.

This friend of mine is in a band called Widespread Panic, which is pretty massive over in America, but they have zero fans over here. I write a lot of their songs, including some of their most popular ones. Their fans hate me because they think I’m a commie, lefty, whatever the fuck they think I am! I said to my son and a musician friend, “I know what it’s like to walk out on stage and be booed by 10,000 people!” But I’ve played with them a lot – if I ever play for 35,000 people, it’s because I’m playing with them. The bass player, Dave Schools, and I had a band called Stockholm Syndrome. We did a couple of records and toured Europe a lot. We were joined by guitarist Eric McFadden and Wally Ingram, and all these different people. So, me and Dave from Widespread Panic are really good friends. He’s also produced a couple of my records. And he had this idea, “Most of your big songs to your fans and even the ones that Panic play and blow the roof off for 30,000 people have no studio version.” These were big fan favourites like our Little Women song ‘Live Radish Head’; ‘Goodlandia’, which had been recorded live on a radio station; ‘Mouthful of Copper’ with The Jackmormons and many more – all songs that are really important to our fans but had never been recorded in the studio. Dave was making a list of these songs with Jim Scott (Tom Petty) involved, and we were thinking that we should cut the ones that are never going to make it, a B-list, like ‘Electra Glide in Blue’ and ‘Whatever’s in the Basket’. Then the thing with Dave fell apart – funding or something.

We have, like, 375 songs – we could play two 90-minute sets a night for 15 nights and not repeat a song. And they’re good songs – songs I’d play in front of people. We started recording these songs. Originally, the idea was to cut them all to 45s and put out a box, but then the money was an issue. So, we’ve been sitting on them and just decided we would release them. There’s supposed to be four records.

I didn’t pick the track listing – I have a hard time listening to my own music, particularly if I make a ‘normal’ record and my head’s been in it for a year. By the time it comes out, it should be hard to get me to play the songs from the record. That is, until I started coming over to the UK because people had a very short list of songs of mine they’d heard, and they wanted to hear those songs. They want to hear ‘Dead Confederate’ every night!

These songs we recorded are both good and bad: the songs are good, but it breaks my heart that at the time, nobody thought this was good enough to record. We’re not the type of band people that talk about the music when we’re done on stage. But, we walked off stage the other night in Seattle, like we have for 30 years, and we’re all saying, “Did we just dream that or was it one of the best shows we’ve done in a decade.” Everything we’ve ever done is taped or filmed. It was an insane show as a three-piece, and I’m mad because I realise people are never going to let something like that open for them – it’s too loud, too fucking incendiary, or it’s drug reputations. It’s always been like that. We were all ready to play with Pearl Jam, and at the last minute, they decided to put a band between us and Pearl Jam—a British band called The Temperance Movement, kind of like The Black Crowes. I remember thinking, “Good luck,” which I know sounds super arrogant. I’m normally self-deprecating to a point where people are uncomfortable with it! I remember Mesler hearing ‘Pink Light’, which is on the new record, and saying it sounds like a big top 40 hit. That’s the only time I’ve ever heard that from a label.

Andrew: It’s like an alternate reality of songs – an alternate career if they’d been the ones originally recorded in the studio.

Jerry: I like our records! I’ve made records in some of the nicest studios in the world, depending on who was paying and what coke dealer or billionaire was interested – we could always get music funded. That’s getting a little more weird now.

I’ve been playing with these guys from Sweden, The Dimpker Brothers – Martin plays a kick drum and guitar, and Adam plays electric and bass pedals. I brought them over to the US for a tour, just the three of us, and people thought it was the most fucking amazing thing ever, especially their voices. It didn’t speak to my friend, but his daughter liked it. I felt that was the point because we need to expand the demographic that way. The 20- and 30-year-olds are talking about people like MJ Lenderman – his cover of ‘Dancing in the Club’ by This is Lorelei was the thing of the summer in the US. I went to a show the other night, and there was Patterson and old people, but there were also young girls and trans people that I know, all these people. It was pretty much the Americana thing with heavier guitars, like Crazy Horse. These artists like this – we need to make new legends. That’s not to say anybody’s going to argue that those last Rick Rubin records with Johnny Cash weren’t full of the greatest ideas in the history of music, like ‘Personal Jesus’ or the ‘Hurt’ video might be the greatest ever made. When I watched that, I was kicking heroin for the second major time of my life. The first time was in ‘95 when I was with the Jackmormons, then I was sober a long time. The next time, I’d got married. We’d only been married a couple of months, living in Harlem, and my wife was going to leave. I was kicking, feeling really fucking sick, and then that video drops, and you might as well have taken a cleaver and slammed it into my heart.

Earlier, we were talking about a confession with my priest. I told him that you could sum up my life in two words: ‘damage’ and ‘fear’. My whole fucking life. I’m scared of everything. I didn’t realise it until I was in my late ‘50s, but I’m still just this frightened little kid, always overcompensating. You want violence, I’ll show you ultraviolence. You want fucking rage, this emotion, that emotion, I’ll show you. My whole life, I’ve been trying to be this thing that I’m not, and then my job is even more like that. Anyway, I’ve built this life, this career in music. A lot of people don’t like that my music is really personal because it can get very uncomfortable. I never tell it in the second or third person. Robbie Robertson always wrote about anything but him. I don’t write ‘The King of Oklahoma’ and can’t write like Jason Isbell or The Truckers. When I write, generally, this is not a character. I haven’t written very many songs about something else. ‘Ten Killer Fairies’ links to the cartels, rather than something I was involved in or connected to.

I was writing with Bob Weir and John Barlow by text. These guys were like heroes, and it felt like I’d been invited into a secret room. I was in Mexico City and was writing another song while waiting for lines for the song we were working on together. In the meantime, I wrote ‘(I’m in Love With) Hyrum Black’. Bobby was like, “I can’t sing this one, from the woman’s side of things.” Barlow’s like, “I don’t know, Bob – it’s one of the best fucking top 10 country songs I’ve heard since 1963!”

That’s the thing – in the face of failure, it’s about not giving up. When I die, there could be a number of epitaphs people could use. John Barlow always used to say, “Jerry, you’re that guy that took all the advanced classes but none of the beginning ones. You’re the Bruce Springsteen of fucking Utah. You should be the biggest singer in the world.” One thing people could say about me is that I never phoned it in, right? I never walked on stage and went, whatever, like it didn’t matter. People might think that’s what narcotics do. No, narcotics make you less afraid. All that fear – I’m still curled up and want to throw up every night before I walk on stage, whether it’s in front of 5 people or 5,000 people, it’s always the same.

Anyway, for The Panther Tracks, it wasn’t really a record I planned. It’s stuff that’s been sitting around, and there’s so much of it. We had four records worth of songs that we had tracked with the Jackmormons, and Dex and a few other people talked about releasing them.

Andrew: You mentioned earlier that you didn’t choose the songs yourself. How did they get selected?

Jerry: It was primarily Dex. Like I said, there’s four albums worth of material, and each one’s supposed to have a new song that’s just been cut. This one has ‘New Lincoln’ on it, which I love. There’s another one called ‘I Think I’m Here’ that’s killer. Originally, we released some of the tracks as part of this paid subscription thing. It was sixty bucks, and you got a new song every week, or two a month. It wasn’t a big success – maybe four or five hundred people signed up. We waited a year after that stopped, so they didn’t feel ripped off. Then I wanted to just throw it all online for free, like, “Fuck it, just release the whole thing.” But people were like, “Whoa, you can’t just do that.”

Andrew: So who actually made the final call on which songs made it onto “Vol. 1”?

Jerry: It was Dex, my manager, Carson, and my friend Danny from Portland, who’s got this cool little label called Cavity Search. They were the first guys to put out work from Richmond Fontaine. Danny’s been around forever; he signed Elliott Smith back in the day. He got involved because he’s always been a fan. He used to work with the band Mother Love Bone, actually. I used to date the singer’s wife. Then Andrew Young dies, and they do ‘Temple of the Dog’ with the Pearl Jam guys and Soundgarden, and then Seattle explodes. Anyway, Danny eventually comes to work with me in Portland, starts this label, and I trust him implicitly. So, it was some consortium of those three – Dex, Carson, and Danny – deciding what fit together and what felt right thematically.

Andrew: And the record does feel like it fits together. There are lots of collaborations, too. You mentioned the Dimpker Brothers before, and you’ve got Wally Ingram playing on there as well. What’s it like working with those guys and others on the record?

Jerry: Yeah, I’m trying to remember who’s even on this thing. I met the Dimpker Brothers as an opening act with Our Man in the Field on a Swedish tour. Alex from Our Man in the Field said, “Hey, these guys just want to get up and play with you.” And I’m like, “Yeah, okay, sure.” At first, with the kick drum and bass pedals, I thought it’d sound like some fucking Holiday Inn band, you know? It was Stockholm or somewhere, and I figured that I should be good. But they got up there, and holy shit – they were good. I always tell my band, “Don’t fuck up,” and I told these poor guys the same thing, but they nailed it. They were so good and so sweet, and then my family stayed with them later. I just love them, and we became family. There’s really something when we play as a trio. I’m kind of this angry ball in the middle, and they’re on either side of me, singing like angels. It’s incredible. They were in town because we were writing this record we were supposed to do together.

Wally and I go way back. We were in that band, Stockholm Syndrome and toured a lot together. My wife will tell you the best record I ever made is “Civility”. My dad had just died. I was down in La Jolla – he’d died kind of suddenly – and I went to my brother’s place in Mexico to write, where I write a lot of songs. I went down there, wrote a bunch of songs – a lot of “The Beautiful Madness” was written there. I wrote the songs that would become “Happy Book”, songs about my dad dying, like ‘Ship’ and ‘LAX’.

Then I was still down there because my mom was a puddle of grief. Wally called me and said, “Man, you need to get out of the house. Come up to Vista.” There was a guy he knew with a studio, and we made “Civility” there. Terry – my wife – still thinks that’s the best thing I’ve ever done. That song, ‘Civility’, means a lot to her. Jenny’s on that record too. She’s basically part of the Jackmormons at this point, for all intents and purposes. We never really had another keyboard player. Honestly, we’d rather play without one – we’re a good three-piece, I would argue. I mean, who’s the toughest three-piece band? I’d love for my band to play something over here that people are actually at, where people get it, you know? We came over a few times, and we’d play Bristol for nobody.

Andrew: It’s difficult, isn’t it? Coming over and starting again?

Jerry: Yeah, coming over and starting again, totally. I haven’t really heard those sort of bands here. I don’t think people here ever really knew the band. Like, no one’s going to go, “Hey, let’s put these guys on to open with The Verve.” Even though we rock. There’s stuff that fucking rocks. I actually like that last Arctic Monkeys record, but we’d never really fit with that. We’ve got ten years of reggae in us, you know? So people would be like, “What the fuck is this?” Like, what does it sound like? It’s like if Steve Earle fronted U2. Or if ZZ Top had Burning Spear’s guys in it. That’s kind of our thing. It’s the spaces. That’s what I love about U2, by the way. I don’t give a fuck what anybody says, they’re incredible live. It’s the spaces between the bass lines, like reggae. That’s how I play, even though we’re a rock band. The Jackmormons groove that way. We come from that instead of punk or straight-up rock ‘n’ roll or whatever.

People sometimes call us a jam band, but we don’t take endless solos. We’ll sit on a groove for ten minutes, sure, but it’s not about soloing – it’s about the trance, the repetition, the moment. I’ll wander out into the crowd, hug people, tell them I love them, tell them God loves them, whatever the fuck I’m doing that night. I used to jump on the crowd, but only because they were holding me.

All those people, the collaborators – they’re like family. Little Sue, for example, she’s a Portland icon. Last night was the Oregon Music Hall of Fame. I was really excited because my friend Casey Neill got inducted. Little Sue got inducted before I did! She’s got this voice… We’ve done a lot of stuff together. When we sing, it sounds like two people who’ve been married for ten years, fighting and fucking and loving each other all at once. That’s what our voices do together. A lot of people have come through the imaginary four Panther Tracks records.

Andrew: Let’s go through some of the songs on the new album. The opener, ‘Pink Light’, is a big song. I’ve heard a few stories about where that song came from – the story about the light in the mountains, the story about the minister and the story about one of you near-death experiences. Could you summarise all that for our readers?

Jerry: Where did that song come from? Well, the minister had come up to me long after the fact and said, “I love your songs about Christ and your connection with God.” One is called ‘The Jump’, this big song I do about my friend jumping 60 feet off a roof, wasted on Xanax and coke. He’s about 70 years old and doesn’t care if he dies. But the minister thinks it’s about jumping into the arms of the Lord. And then the song off the new record, ‘Pink Light’, when he’s praying – when someone is dying or grieving – he sees God fill the room as a pink light, and now I’ll never be able to not think about that when I’m playing the song. When I wrote that song, my girlfriend at the time, Lori, played a cello part on it. For writing the song, two things happen. One, at the time I was living in Salt Lake and really, is this thing that happens sometimes in the winter where the sun reflects off the Wasatch Mountains behind you and the Oquirrh Mountains. There’s nothing out there except a big copper mine. The light bounces back and forth, and it’s pink. We could be sitting here, and it would look like we were in a pink cloud. It’s pretty wild! Pollution, I think! Then, the second thing – I had overdosed on speedballs, which at the time used to be coke and heroin. You’re doing a lot more heroin because you’ve got this coke moving you along. The coke wears off faster, and then you’ve just got this big load of dope. I was with these people I didn’t know in a hotel room, although not the hotel we were staying at. My tour manager was taking me to a gig down in Garberville in California. I remember shooting the speedball – nothing on earth feels like that. The last thing I remember is watching Sinead O’Connor’s video for ‘Nothing Compares 2 U’ and seeing the tear fall down her face. It’s my last thing. And then, in my mind, I’m in this pink fucking light – that’s all I remember. Sinead. Pink. I wake up to being defibrillated in the hospital. I survived because of a series of events – my tour manager happened to be walking by to see someone else at the hotel that we’re not staying at, and sees the car belonging to one of the people I was with or something. The door’s open, so he walks in. I’m in the bathtub with the cold water running. They’d just left me. They didn’t throw any ice on me – they all take off. He puts me on his back and runs out the door, bangs into this guy we know called Tommy Short, who runs a club in Fort Collins, Colorado and has no connection to Oregon, other than us, but he’s there for a Ducks football game. He just happens to be walking by and literally runs into Jeff, holding me and Jeff’s like, “I think Jerry’s dead or he’s dying – he’s not breathing.” Tommy had his truck there, and they throw me in and take me to the fucking hospital. Apparently, the first doctor says, “No, man, he’s gone.” But the second doctor says, “Fuck it, we can do it!” When you first come out of that, you’re pissed because you’re not high anymore. It was early ‘90s, so I’d been wearing cut-off fatigue army pants with tie-dyed long underwear underneath. I remember thinking, “Did I just almost die in tie-dye?”

Something like ‘Dead Confederate’-I probably wrote in five minutes. I literally walked out on a friend’s porch, fucked about with the chorus, came back and played it. My friend said, “Where’d that come from?” I just wrote it while he smoked a cigarette. Stuff comes to me like that quite often. Often, you sing a song and part of you is like, “What are you writing this about?” and another part is asking why people are singing or crying. It’s obviously nothing to do with what I think the words are about.

Andrew: What about ‘Way Too Loud’? That was a song I think you wrote with Danny Hutchens from Bloodkin – is that right? What’s the story behind that?

Jerry: That could be a large story. Me and Danny were supposed to sign to Capricorn Records with Widespread Panic and Colonel Bruce Hampton. In the 11th hour and 59 minutes and 30 seconds, they decide they’re not signing me or Danny. This is Phil Walden (co-founder of the label). He’d been calling my mom, who didn’t know he was the President of Capricorn Records. She said, “He keeps calling and saying, ‘Mrs Joseph, Jerry’s a white Otis Redding and I manage Otis Redding!” She didn’t know who Otis Redding was either. I thought it was in the bag, but Danny and Bloodkin were the real deal. I think Patterson Hood or anybody who knew Danny would agree that Danny was better than me. He was definitely in the top five unknown American writers. He was fucking brilliant. He did a video thing too during COVID, but he had a stroke. I loved him. He was everything. Capricorn had sent him to Portland. When he comes off the plane, he looks like Steven Tyler. We go to a hotel, and I ask him what he’s got, and he’s got a bag of black beauties. I’ve got a gram of black tar heroin, and he goes, “Sounds like we got a song,” and we start writing songs, including ‘Way Too Loud’. We specifically wrote that song for Widespread Panic because they had been covering both of us, and we wanted to write the quintessential Widespread Panic song. To this day, I play for those guys, and they don’t see it. How could you not! Again, it was a fan favourite that we didn’t play all the time. It was on this obscure live Little Women record. It’s another one where I sit listening to it or singing it, and I wonder about who wrote what line. It takes you back there. I would really love to do an album of Danny Hutchens covers. Here in Europe, I was trying to get Ella Spencer to cover one. Nobody really knows who he is, but he was fucking amazing, and you could just pick anything.

Andrew: Another one off the album that you’ve played live a lot is ‘You Want it Darker’, the Leonard Cohen cover. The version you’ve got of it is very emotional, very intense. What were you trying to achieve with the tone, treatment and arrangement of that song, and why did you choose to cover that one?

Jerry: We have a couple of songs like that, like ‘Istanbul’, that I wrote on the roof of a hotel in Istanbul as I was heading to Afghanistan. Everyone was telling me not to go because I would fucking die. But the aid workers had asked if I would come and continue working at this underground music school that an American who was married to an Afghan guy was running. If they kept a list of students, I’m sure all those kids are dead. In this song, ‘Istanbul’, I’m doing this huge kind of rap. I think it was my first kind of Nick Cave attempt or something. I came late to the party with him. One day, I walked into my apartment in Harlem, and my wife was standing there bawling. When I asked why, she puts on ‘There She Goes, My Beautiful World’ by Nick Cave, and then he became my musical God. If I had a musical God, it would be him. Anyway, we were looking to do something that filled that hole, that kind of minor key dirge, and I’d been listening to that song. It was years before the Leonard Cohen tribute, although Iggy Pop does it quite like us – the same sort of idea. I think I get all of the words wrong. The Hebrew word ‘hineni’, meaning ‘Take me God’ or ‘I’m with you, God,’ is a fucking heavy word.

Andrew: Tell us about the new song ‘New Lincoln’. What’s the story behind that?

Jerry: ‘New Lincoln’ was right before the Biden-Trump election. I’d just written “The Beautiful Madness”. Songs like ‘Sugar Smacks’ and ‘The Man Who Would be King’ make these references to election day and death. There’s a bunch of songs sort of addressing this subject. Usually, when I write politically – like my song ‘American Fork’ that I played in London the other night or ‘Ten Killer Fairies’ – it’s brutal. Even Woody Harrelson was like, “Dude, this is great, but this is brutal.” And what sucks about those songs is you could play any one of them right now. They still would still fit, still relevant. They’re still running narcotics; it’s even more brutal. ‘New Lincoln’ was totally ripping off ‘Teacher’ by Jethro Tull. When I finally got to England for the first time, all I wanted to listen to was Genesis, Yes, and Jethro Tull. Even when I lived in New Zealand for a year, which was like faux Britain! There were sheep; it was cold. I remember reading “Lord of the Rings”, smoking Buddhist sticks, looking out of the window. Then, we go to see “Lord of the Rings” as a band, and I’m crying and they’re wondering what’s the matter. I’m thinking this is it, exactly what I was looking at. My dad had this house at the top of this road; there was a paddock and a little pony, like the fucking shire! That’s what I looked at when I read the book, so Peter Jackson just sort of grabbed my memory.

Anyway, I had that riff like the song ‘Teacher’, and I had the title, which came from a conversation about how we needed a new Lincoln. I think Biden was a great President, but he should have stayed a one-term President. Then he would go down in history. He was more effective and remarkable than some Presidents, but he wasn’t an orator like Obama, Clinton and Reagan. Those guys were massive when it came to talking to audiences. We weren’t sure Biden was going to win – we were looking at a second Trump term, which would have been better then than now because they had four years to be angry and to decide what to do if they got it back. When I sing, ‘Shake the cages / Hear your babies howl,’ that was about when they were putting children of immigrants in cages. We haven’t played it live very much because it’s hard! Somebody had also been talking about cars, so I was just jamming this metaphor of cars and inspiring political figures into one – drive like you stole it.

Andrew: Talking about playing that live, you’ve always been an incredibly intense, emotional performer. It looks like you give everything of yourself up there. What does a show take out of you, and what do you get from that connection with the audience?

Jerry: Well – now? There are serious conversations about being in the last act or on the last lap. What do you want to do with what you’ve got? What have I got? Ten years? I mean, I’ve been pretty lucky. I remember seeing Nick Cave in “20,000 Days on Earth”. He was the first person I ever heard talk about how, before a gig, for like three hours, you’ve got nothing. You’re sitting in the green room or on the bus headed to the show, curled up in a ball, sick to your stomach, thinking, “I’ve got nothing to give.” You’re nauseous, you’ve got the shits, whatever. Then all of a sudden, the house lights go down, someone says, “Ladies and gentlemen, from Melbourne – Nick Cave.” And he steps out, and it’s like God – or whatever – goes boom! But not until the moment that he actually steps on. I totally got that. That’s what it’s like. One minute you’re empty, the next you’re lit up. Like a puppet. It taps me. If it hasn’t wiped me out by the end, it wasn’t a good show. I mean that. Even with the Jackmormons, the model was – even though we weren’t playing fast – we were quasi-punk for the most part. We want to look like The Clash at Shea Stadium when they came off stage. Every fucking night, somebody throws a guitar and they just fall over. Just wrecked. They were done after 30 minutes, and we want to play like that for three hours.

You know, when I was a kid, I played music because I couldn’t play sports. I’m unattractive and can’t throw a football. Like, how am I going to meet girls? I wanted to be able to kick the shit out of the jock guy too, beat his ass, get his girlfriend and be in a band. That’s the truth. That’s where the fire started. People ask where your muse comes from. Now, it kind of started in sobriety – I’m married. I’m sober. I’m not getting paid very much. Why the fuck am I here, right? All the motivations of the past… What I’m making at the moment, I would have killed for as a kid, but all those things, the trappings of playing in a band…

I was watching my son’s friend in a punk band in a punk metal place down the street from me. There was a chain link fence with the bar on one side and the stage and pit on the other. One guy saw me and said, “Jerry Joseph – I thought you were dead!” I’m watching this mosh pit of boys and girls, and I’m crying. My son’s like, “Why are you crying, Dad, in front of all my friends?” And I say, “Because I forgot that this was fun.” There was a time when people were clapping for us, girls were talking to us, the drugs were free, and we couldn’t believe we were getting paid for it. It was fun. But that was over quickly. People start writing about you. The first time you’re responsible for this group of misfits getting paid. I didn’t have a blueprint, and I didn’t have a friend in the industry. I think it’s often very different now. We were just making it up, especially national tours. We were moving with the punk bands, staying in the same hotels. Every so often, we’d run into the spandex guys. We were like the reggae hippies, with dogs and twelve people in the van. Then, there were the punk guys who also had dogs.

So, I got to that point of asking what I was doing, why I was here. Now, it’s like that Henry Rollins quote, “Better be fucking awesome.” Then it’s moved again lately thanks to my priest, my sponsor and my therapist. In January, I’m going to India for a month – I’m told that it’s a pilgrimage, not a vacation, and I’m trying to get closer to that place I reach on stage. Now, my opinion is that if I can’t leave God and love in the room, then it’s been a fucking failure. If I can’t make one person feel that. I know it sounds trite and everybody is always going on about love, love, love – love unlimited – but we still all hate each other’s guts! And nobody from that music silo will ever listen to anybody from this music silo. I know it gets overused. I’ve kept journals every night since rehab in 1992, only a paragraph or two about where I am, and it’s like signing off with thanks to God because I’m talking to somebody here. It’s not always for your future children – who are you talking to? Now, I’m 64. I have faith. I’ve also seen too much of the world to not go one way or the other. When you’ve seen the things I’ve seen, you either think there’s nothing when we die, just blackness, and it’s over, or my choice is to believe that this life is just part of it. I’m Catholic and have listened to a lot of Catholic people talking. I’ve also listened to a lot of Ram Dass (an American spiritual leader and guru), Jack Kornfield (Buddhist writer and teacher), Sharon Salzberg (Buddhist meditation pioneer). Buddhists and Hindus. I probably listen to more Krishna Das than I listen to other music. I’m getting to what it’s like on stage. When we were chatting earlier, we talked about how it is at the end of a show, and I say, “I love you and God loves you.” People break, you know? Every fucking night, somebody just melts. Therapists, sponsors, priests, spiritual guys say that you owe it to deliver this message that we’re not alone, that there’s more, that we’re loved.

Some people look at me and say I’m the guy who can show how to wrap a baseball bat with barbed wire and where to hit the ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) guy so it takes his mask off. Okay, I’ve got a mixed skill set, but there’s got to be a way to combine those. I’ve got all the ego and self-centredness and all the things that make anyone get on stage. I have a fan base that’s been around me a long time. I’ve been playing in bands since I was 15 – Little Women were starting to kick in ‘84 – and there’s a spiritual connection to these people. I do get played a lot at funerals and marriages. But way more funerals! People get buried to songs like ‘Loving Kindness’. So, it’s a different relationship. There’s a real intimacy in that. You’re part of people’s lives in a deep way.

I think that is the point. I’ve seen a video of Janis Joplin crying on stage, singing ‘Piece of My Heart’. Amy Winehouse was that fucking good, too. No matter how horrific the rest of that story is, she picked up that microphone, and there was that connection. So yeah, I give everything I’ve got, because they’ve given me everything too. If I can’t leave God and love in the room, the show’s a failure. If I can’t make even one person feel seen or connected, it doesn’t matter how tight the band played.

Andrew: Speaking of connection to others and giving love, you’ve previously mentioned your experiences working in war-torn places and refugee camps. Can you talk a bit about that – what those moments taught you about music and connection?

Jerry: Yeah. I was working with these kids in refugee camps. These were kids who’d survived ISIS slave camps, and the Yazidi had just gone through genocide. I’m trying to get these girls to at least go, “Yo, yo, yo,” like Bob Marley, trying to teach them ‘Three Little Birds’. They’ve all been raped. They’ve all watched their parents burn in fucking cages. All of them. Every one of them has witnessed an October 7th event in their community. This century, no one has an exclusivity on fucking horror. I’m trying to get them to sing, and they’re not looking at me. At one point, I tried to help a girl make a chord on the guitar and touched her hand and thought I was going to get shot. They’re all staring down. Finally, I look at my Kurdish-Yuzi interpreter and say, “I need you to tell these girls that I need all of it. All the rage, all the fear, all the hurt, all the pain, all the horror, all the love, everything – when they sing yo, yo, yo.” She interprets, and they kind of lift up, a few more goes, again, louder, “YO, YO, YO!” Twenty girls get up and give everything they’d been holding back. I looked over at Charlie Freeman, the guy I travel with and said, “That is the fucking sound of God.” For music, that’s the point. Who are we singing to? In a million years, I’m not saying it’s got to be a hopeful message.

Andrew: You’ve always been a political artist, but also deeply personal. Do you think something’s changed – has that political energy gone out of music?

Jerry: Those punk rock kids were lighting up the room – I was stoked, so excited, so accepted. Musicians might never be political again like they were in the ‘60s, when they were the kings and queens, maybe more than movie stars with private jets. Now, they’ve been replaced by tech bros, and nobody wants to follow those guys around. Stevie Wonder, Staples, John Lennon – they mattered – all those relationships. I was trying to teach my grandkids about the Black Panthers and Zapatistas the other day. I spent time in Nicaragua with the Sandinistas when I was younger. The struggle and the music used to be hand in hand. Now the music is so divided. What’s the commonality? Clearly, I think about my own salvation. I’d love to say it’s about saving other people, about going to Afghanistan without a military escort, all your guitars and one friend; about going to Kabul and being brave and caring so much about these kids. But actually, it’s about my own salvation.

Andrew: That’s a perfect place to close our interview, Jerry – it’s about your own salvation, deliverance, being saved. That’s a pretty special way to finish. Thanks so much for your time and being so open with Americana UK.

Fantastic interview Andrew, really shows up the hinterland behind Jerry, both his music and his humanitarian efforts.

What Paul said.

Great interview.