Sid Griffin needs no introduction to these pages. Whether as co-founder of The Long Ryders, founder of The Coal Porters, solo artist, or with others and a frequently published writer, readers will know something of this prolific creative spirit from Louisville, Kentucky and long-time resident of London. What may be less well known is his more intimate solo performances, such as this at the regular Twickfolk Sunday evening held at the Cabbage Patch pub in Twickenham, south-west London. Unaccompanied save for a couple of duets with his wife, Rhiannon, and armed only with an acoustic guitar, banjo and mandolin, Griffin, through his songs and stories, revealed a fascinating insight into a life in music on both sides of the Atlantic. Even if stripped of the frantic, electric jangly sound that defined the Long Ryders as standard bearers of 1980s alt-country, many of the songs were familiar, others were more recent creations. But what flowed throughout the evening was Griffin’s rich stream of tall tales and anecdotes. A reviewer once described Griffin as “an Aesop meets Rabelais” storyteller. If moral lessons were few, humour and character abounded during his two sets.

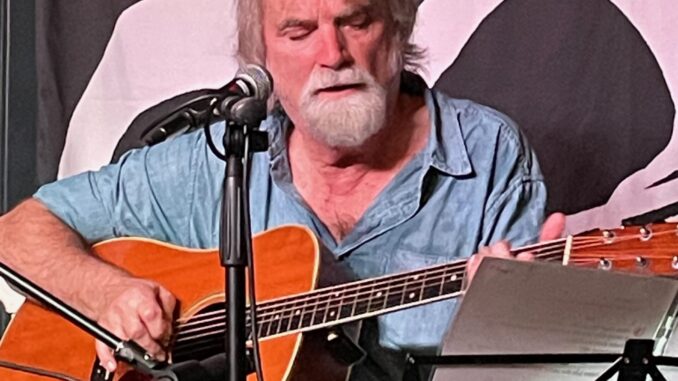

The setting was equally intimate, a low platform on which two chairs competed for room with a mic stand and a couple of monitors. The audience sat front and side, and through this tightly packed group wound Griffen, who, on taking his seat, apologised profusely for his head cold. He described his voice as somewhere between Joe Cocker and Tom Waits. He wasn’t wrong but driven by either consummate professionalism or his sheer irrepressibility (or both), the show had to go on. He did have a reasonable excuse for feeling slightly weary, having been out on tour with his bluegrass band, The Coal Porters, then celebrating his 70th birthday with a show in central London two days previously.

Confessing, “I have to start with this one” Griffin blew away the years and germs with, well, what else but the Long Ryders anthem, ‘Looking for Lewis and Clark’ Even if sitting down and a voice more of a rasp than youthful defiance, Griffin still belted out, “I thought I saw diplomats hawking secrets in the park” with menace, as his banjo might testify. His energy added heft to his sincere comment that wherever he may be, it is always a privilege to play. With that, off he went. Going back to growing up in Louisville, he explained ‘Son, Won’t You Teach Me To Waltz?’ is about how his mother managed to keep dancing after his father died. Moving to another house, this time in LA, Griffin switched to guitar with more than a hint of jazz for the lighter but equally reflective, ‘That’s What They Say About Love’.

Names abounded in Griffin’s anecdotes. Using lyric sheets was ok because Lucinda Williams said so. He declared his deep love for Gram Parsons and The Byrds, the original inspiration for his group, The Coal Porters, in particular Gene Clark, who he knew. A story about being able to name the lineups of The Zombies, Iron Butterfly and the LA Dodgers was Griffin’s evidence of a brain too full to handle a big job like being a doctor or lawyer, so music it was. ‘Why I Play Guitar’ added the detail. Griffin has busked, he accepts “it’s sounding great, but it’s a little late/ for you to be a star” but via The Beatles, Bob Marley and BB King, to name a few he admits he plays guitar when he’s “happy”, “lonely” or “blue” as a passer-by drops the odd coin his way.

A feature of Griffin’s songs is how he can set his perceptive writing to themes that range from the deadly serious to humour, displayed by two songs from his 2024 album ‘The Journey From Grape to Raisin”. On ‘The Last Ten Seconds of Life’, Griffin speculates how a near miss while driving might have panned out had he been less fortunate. By contrast, ‘I Want to Be the Man (My Dog Thinks I Am)’ speaks for itself. Griffin’s wife Rhiannon joined him for two lovely duets, first the Everlys’ ’Brand New Heartache’ then ‘Ivory Tower’ from the Long Ryders’ debut ‘Native Sons’. The latter was written by former Long Ryder Barry Shank, who quit to become a doctor.

Griffin returned for a second set, nursing a glass that looked like lemon tea. Whatever it was certainly worked, as he seemed invigorated. With no more lyric sheets, he moved into more traditional territory with ‘The Light That Shines Within’, following up with an English folk song from 1745, ‘John Riley’. With ‘Oh Didn’t They Crucify My Lord’ that featured on an early Gram Parsons album, Griffin obeyed his mother’s devout Christian command that if music had to be played on a Sunday, it had to be gospel. With his mandolin, Griffin tore into the Long Ryders classic, ‘Final Wild Son’ and then, standing in front of the stage, ‘The Day the Last Ramone Died’. In a more sombre moment, Griffin noted the passing years. Reminded of a tense moment while dealing with requests while busking, Griffin gave a swift rendition of ‘Leaning on a Lamppost’ that got the audience going too, before returning to his roots with ‘My Old Kentucky Home’. Since he opened with ‘Lewis and Clark’, Mr and Mrs Griffin wrapped up the evening with its B Side, ‘If I Were a Bramble And You Were a Rose’.

Griffin may not have been feeling at his peak, but performance-wise, he was definitely at the top of his game. For a show full of humour, insight, and above all, a life in music, Sid Griffin is hard to beat.