When I went to see Ron Sexsmith in London’s Islington a few years ago, his friend Nick Lowe was in the audience. The Jesus of Cool acknowledges a fine writer of popular song when he hears one, as do many readers of this piece, to whom I do not need to spell out the brilliance of the man whose albums bear the credit Ronald Eldon Sexsmith.

You know one of his melodies when you hear it: hummable, effortless, wistful and memorable. You’ll never forget his face, his maudlin hangdog expression and, above all, his croon. There’s no bolshiness or bravado in his songwriting, which lets the listener in and helps soundtrack their lives, or comfort them in difficult days. Three decades after his breakthrough, he is still writing, recording and performing, making annual visits to the UK including the London Palladium in 2024 and Cadogan Hall in Sloane Square on a Monday night in February 2026.

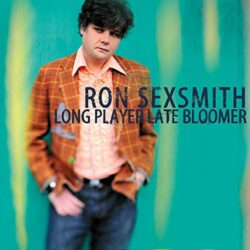

Can’t Live With It: “Long Player Late Bloomer” (2011)

Obviously it’s stupid to denigrate the quality of the songs themselves, so my focus here is on the production of this album. Its release was accompanied by “Love Shines”, a documentary which laid bare Sexsmith’s aims to break through to a wider audience after 15 years making music for a loyal, committed audience. The singer called it a “radical and drastic” move, something every artist needs to do once in a while. The album is not a failure, just an outlier in his catalogue.

Obviously it’s stupid to denigrate the quality of the songs themselves, so my focus here is on the production of this album. Its release was accompanied by “Love Shines”, a documentary which laid bare Sexsmith’s aims to break through to a wider audience after 15 years making music for a loyal, committed audience. The singer called it a “radical and drastic” move, something every artist needs to do once in a while. The album is not a failure, just an outlier in his catalogue.

The issue comes with the production. Bob Rock had worked with Metallica and Michael Bublé, and Sexsmith sought his wizardry to bring a commercial sheen to his material. The intro to ‘Believe It When I See It’ is evidence of this, with a sparkling guitar line and spiky cymbals; drums come from top session player Josh Freese, while Paul McCartney’s guitar player Rusty Anderson is one of several to feature across the album.

There’s so much ear candy trying to hook the listener, but because of the quieter verses, which are dominated by a piano line full of diminished chords, the song veers this way and that. The payoff, “I’ll believe it when I see it with my own two eyes”, is also fairly weak. The middle eight slathers Sexsmith’s multitracked voice in production trickery, too, something which happens on the chorus of the album’s notional title track ‘Late Bloomer’, whose guitar solo looks towards arena rock.

‘Get In Line’, the album’s opening track, sounds better in a solo acoustic version, where Sexsmith’s vocal line is allowed to breathe; Rock chooses to start some lines while the previous one is still ending. ‘Every Time I Follow’, where music dispels the narrator’s “lonely and disillusioned heart”, is pastiche Paul McCartney, which reminds me that Phil Spector also brought too much production to ‘Let It Be’, rather than letting the song speak for itself.

Elsewhere, ‘The Reason Why’, which is in an unusual 3/2 time signature, has a chunky solo electric guitar passage at odds with the harmonica hook of the opening seconds. ‘Michael and His Dad’ (“it takes much more than love”) is anchored by piano notes an octave apart and a strong but inapposite groove from the drums, which recur on ‘Middle of Love’. That song makes room for a wordless answering hook that sounds like “wooo-doo-doo” and the strange, backwards-looking lyric “from email to a fax machine”.

‘Love Shines’ (“in every nowhere town there are somewhere dreams”) was called “a granny-friendly showtune” in one review, an example of the “cloying” nature of the album which takes him to Elton John territory (the singer was a childhood member of Elton’s fan club). The same can be said of ‘Miracles’, which lays on the strings, and ‘No Help At All’, where the flute-led hook is underscored by light chords from the keyboard; the latter suffers from rhyming “writing on the wall/until I hit that wall”. The eclectic instrumentation across the album takes in dobro and wire-brushed drums on ‘Heavenly’, and slide guitar and honkytonk piano on ‘Eye Candy’, whose middle eight slips in and out of waltz time. That song includes the doggerel “upload came download with a truckload of trouble”.

Closing track ‘Nowadays’ reminds us of the sound that brought Sexsmith to prominence: acoustic guitar at the front of the mix, light pedal steel backing, standalone melody and lyrics that contrast then (“used to be I dealt with devils on my own”) and now (“a place that’s safe and warm”). The album helped Sexsmith play bigger venues in the UK, where he could offer the rest of the songs unburnished by studio wizardry.

Can’t Live Without It: “The Vivian Line” (2023)

I was enormously impressed with this album of vignettes, as was Guy Lincoln in his AUK review; he correctly called it “open-hearted”. Sexsmith himself told this site that the songs “hit me by surprise” during the pandemic. Production comes from erstwhile Sexsmith bass player Brad Jones, who helps us forget Bob Rock’s sheen; there is not an electric guitar solo in sight. The singer noted that he can “sing better” in his old age and thus do more justice to the baroque pop sound he has often worked in.

I was enormously impressed with this album of vignettes, as was Guy Lincoln in his AUK review; he correctly called it “open-hearted”. Sexsmith himself told this site that the songs “hit me by surprise” during the pandemic. Production comes from erstwhile Sexsmith bass player Brad Jones, who helps us forget Bob Rock’s sheen; there is not an electric guitar solo in sight. The singer noted that he can “sing better” in his old age and thus do more justice to the baroque pop sound he has often worked in.

On the first verse of opening track ‘Place Called Love’ (“everyone finds it in their own time”), Sexsmith’s voice and guitar are joined by an oboe, conjuring a completely different mood from “Long Player Late Bloomer”. The middle eight takes off into a different stratosphere, like a hot air balloon entering the clouds. ‘When Our Love Was New’ (“it was ancient in our hearts”) is just as lovely, a modern standard with a gentle chord progression and support from strings and woodwind; the piano outro emphasises the song’s mood.

There’s so much happiness across the record, partially accounted for by a relocation from Toronto to Stratford. ‘Diamond Wave’, written on his birthday in 1988 after Sexsmith kept hold of his courier job, finally makes a studio recording complete with pretty harmonies and a major-key optimism. Similar joy is found on ‘One Bird Calling’, on which he sighs “oh how lucky we are”. ‘A Barn Conversion’, with its chromatic melodies, sounds like the theme tune to the TV property shows that inspired it.

On ‘Outdated and Antiquated’, a tongue-in-cheek title, Sexsmith sings “I believe in the past” and laments how he writes “poems” while others are “on their phones”. This will all chime with an audience which has grown old with him, and they are invited to join in with the closing “la-la” passage. Elsewhere, ‘Country Mile’ has a strident string part and some familiar diminished chords, ‘Flower Boxes’ uses pizzicato strings to mimic teardrops, backing up how “from despair our memories can save us”, while ‘Ever Wonder’ has clip-clop percussion, finger clicks and wordless backing vocals to end the album with a wistful gentleness, or genteelness.

The quality of songwriting is really outstanding. ‘What I Had In Mind’ has a patented toe-tapping rhythm and a middle six, cutting the middle eight two bars short in favour of a harpsichord solo; that passage contains the rhyme “relevance/intelligence/elephant in the room”. ‘This, That, and the Other Thing’, which like a lot of Sexsmith’s best songs is over and done with in just over two minutes, has bars of seven beats in its verse and a warm arrangement, including a Fender Rhodes solo and short flute phrases.

Sexsmith proves himself across the album to be both Burt Bacharach and Hal David, the melodist and the lyricist, putting him in the same category as Paul McCartney or Elvis Costello. We’ll miss him when he hangs up his pen.

Thanks for the article and turning me on to music I had not yet heard!