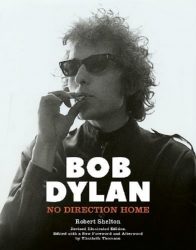

A new re-issue of the classic Dylan biography as he nears his 80th birthday.

Never judge a book by its cover – but in this case that is going to be the first thing that becomes apparent to the reader. This re-issued version of Robert Shelton’s classic insight into what makes Dylan tick has one obvious difference to previous editions: it’s big. An oversized hardback, weighing in at almost 3 and a half pounds, it’s a book that is certainly not hiding its light under a bushel. This edition has been edited by Elizabeth Thomson, a friend of Shelton’s for the last 15 years of his life, and who was also responsible for the 2011 re-issue of No Direction Home. That edition restored much of Shelton’s text, as well as reshaping and updating the book to be in line with Shelton’s original concept of the volume. This current edition is based on that fuller text, but is an abridged version – leaving out much of the background material of Dylan as a Student and also the scene-setting of the cultural background of Woodstock as well as side-tracks taking in Dylan’s contemporaries. Also left out are Shelton’s album by album commentaries and his arguments for Dylan to be seen not just as a singer of astonishing songs but also as a poet. As Thomson points out, the awarding of the Nobel prize has pretty much put that argument to bed. For those that want all that additional material – well, there is still the 2011 edition. So, that’s what’s gone – what’s new?

Simply put this is a lavishly illustrated book, across the 304 pages there’s a picture on pretty much every other page. Early pictures of Dylan can be painfully revealing – a number of people have described their first impressions of Dylan that he was a scrawny kid, and there is here a photo of Dylan diving into a hotel pool at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963 which really brings that one home: it’s beyond skinny and heading for undernourished. There are also reproductions of ephemera such as early handbills for his concerts and hand-drawn posters. These alone are enough to show Dylan moving from the new kid on the Greenwich Village streets to entering into an exalted milieu: here’s Dylan opening for John Lee Hooker, and here’s Dylan supporting the rather less well recalled Greenbriar Boys at a gig that would get a fine review from the New York Times’ folk music critic, Robert Shelton. And this is, in part, why Shelton’s book is such an essential read amongst the crowded market of Dylan biographies and analyses: Shelton was unarguably right there, when Dylan first came to any attention – he was there as a reviewer, he was there as a friend, and would continue to be over the period that the book covers through into the late 1970s. Robert Shelton is also, unarguably, on Dylan’s side as he tried to explain the biography of the man and, as Shelton sees it, the importance of the poetic work that he has produced.

In a matter of fifteen years Dylan would go from the folk singing darling of the left, the natural heir apparent to Woody and Pete, through the most revolutionary approach to rock and roll to the hard to credit it really happened magic of the Rolling Thunder Revue. And a lot more besides, and Shelton was periodically right there alongside him – given access to Dylan’s family when the early mythologising stories unravelled, talking to Baez about the hurt of being musically snubbed when Dylan’s fame eclipsed hers, talking to Jack Elliot about Dylan’s success, chatting with the press pack of Mr Jonses struggling to get what was going on. And, most importantly, talking to Dylan as he came to terms with fame and found it to be not all to his liking. There’s something remarkable in the reported conversations with the originally supposed shy, but already ambitious, ragamuffin of the Greenwich Village scene and the evolution through being the touchstone singer with whom The Beatles wanted to hang to the somewhat bittered by life divorced family-man that the book closes with. Yes – Dylan is contradictory, he’ll say one thing and a different, perhaps an opposite, thing a few days later. He’s restless, and this is perfectly captured. He’ll say he’s moved beyond folk – but he’ll seek out the likes of Martin Carthy when he is in England. He’ll make the claim that his art is not all about money making, but he’ll prickle when he’s queried over his liking for fine hotels like The Savoy. In one particularly extended interview Dylan declares that he’ll explain his songs, but when it comes to it he doesn’t want to dissect them – that wasn’t what he meant by explain – instead he’d rather expound on his complex relationship with Baez and the nature of the universe as experienced by man, and the place of sex within that experience. Contradictory, deflecting and elusive, and unwilling to explain – it is the Dylan of myth and for the majority of Dylan’s listeners it is this book – and Pennebaker’s film of course – which cements Dylan into that myth.

The space such a physically large book offers to include a stunning array of photographs around which the text is wrapped also allows the layout to include large font quotes taken from a relevant interview that entice the reader who is just flicking through to stop and read a section in detail. This isn’t an easy book to read – it’s so darn large that holding it for any length of time is a strain – but it is a book that entices the reader in, and for longer than they’d planned. The 2011 expanded version of ‘No Direction Home‘ was a must have read for Dylan’s 70th birthday, and Elizabeth Thomson’s lavish coffee-table version is equally so for his 80th. As a Dylan primer, it’s in a class of its own.