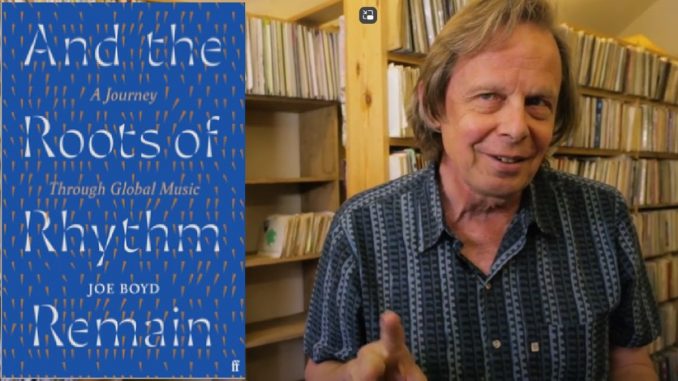

A seasoned American record producer, Joe Boyd has poured his years of experience and passion into this extensive work. On his personal website, Boyd playfully quips, “It’s a bit of a door-stop. Sherpas will be provided to purchasers to help them carry it home.” This witty remark showcases his expertise and hints at the unique perspective he brings to the global music journey, sparking the reader’s interest. As the former owner of Hannibal Records, Boyd’s influence in the music industry is far-reaching. His work has touched many artists, including Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, Richard Thompson, Nick Drake, Billy Bragg, and John Martyn. The list could go on, but we wouldn’t want this review to be almost as long as one of the chapters in this tome.

A seasoned American record producer, Joe Boyd has poured his years of experience and passion into this extensive work. On his personal website, Boyd playfully quips, “It’s a bit of a door-stop. Sherpas will be provided to purchasers to help them carry it home.” This witty remark showcases his expertise and hints at the unique perspective he brings to the global music journey, sparking the reader’s interest. As the former owner of Hannibal Records, Boyd’s influence in the music industry is far-reaching. His work has touched many artists, including Fairport Convention, Sandy Denny, Richard Thompson, Nick Drake, Billy Bragg, and John Martyn. The list could go on, but we wouldn’t want this review to be almost as long as one of the chapters in this tome.

Boyd wrote the excellent “White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s,” which a Guardian journalist described as “one of the most lucid and insightful autobiographies I have read.” This book further examines music from diverse places, such as Bulgaria, Ghana, Jamaica, and Brazil. Boyd, a master of his craft, skilfully intertwines facts, figures, and captivating anecdotes from his own experiences and those of others. This distinctive fusion of storytelling and information transforms this voluminous book into a captivating and immersive journey through what, in the 1980s, became known as “World Music.”

The opening chapter takes us on a journey through the music of South Africa and the political past. “Mbube”, the Zulu word for lion, is used for the chapter title, and Boyd describes the much-imitated high falsetto vocal of Jay Siegel, singing “In the jungle, the mighty jungle, the lion sleeps tonight”. The melody was taken from a 1938 recording of the song “Mbube” about a Zulu boy braving lions in the bush. Of course, we cannot talk about South Africa without referencing Paul Simon and the brilliant “Graceland”. The album is responsible for opening Western ears to something different and musically challenging. Boyd tells us how Simon added the penny whistle to ‘You Can Call Me Al’ as a nod to the Kwela music, the penny whistle street music of South Africa.

Boyd has great affection for Cuban sounds. A detailed chapter describes the island’s early occupation and its ties with America, Russia, and Communist rule, which led to a melting pot of different sounds and rhythms. Boyd explains the establishment and operation of the original Buena Vista Social Club, founded in 1932 in Cuba’s capital, Havana. In 1996, Nick Gold and producer Ry Cooder organised a kind of Cuban supergroup. They recorded an album named after the Havana Club, showcasing the popular styles of Cuban music, such as son, bolero, and danzón. A performance was recorded as part of a documentary with the same name. Boyd discusses how the completed Wim Wenders documentary gets the credit for Buena Vista’s success when, in real terms, the album had sold half a million copies, which is unbelievable for a world music release.

Boyd continues throughout the book to regale us with different anecdotes, facts, and opinions. The section on Jamaican music begins with a tale of how the founder of Island Records, Chris Blackwell, was originally taught to fear and avoid the strange tribe of people called ‘Rastafarians’. Luckily, he built a trust and brought us an incredible wealth of music from those small islands. The chapter on the music of India can’t escape the influence of Ravi Shankar on Western artists such as the Beatles. Boyd tells of how, in 1965, after the Liverpudlian foursome had appeared at Shea Stadium, they were staying at Zsa Zsa Gabor’s mansion. John Lennon and George Harrison were in the tub listening to David Crosby and Roger McGuinn extolling the virtues of Ravi Shankar. Back in London, Harrison went to HMV and bought every Shankar album they had. The final chapter gives us a round-up of how Boyd feels about it and the music business going forward. He makes an excellent point that looking back at minstrel shows or the bufo blackface of the Hispanic World, there was always a White fascination with Black Music. Unfortunately, to use Boyd’s words, “it had to be drip-fed in the guise of a racist clown show.”

Throughout this volume, Boyd shows how governments have tried to repress music. For example, drums were banned in South Africa in case they were used to send messages between different tribes. Now, we face the challenge of technology. Will we lose the inspiration and magic that a group of musicians may have when sitting in a garage, studio, or living room? One person can produce everything as a demo and then ask session musicians to play the parts. Boyd lists examples of spontaneity that will live forever. Lee Scratch Perry would turn on the tape machine the minute Marley, Tosh, and Livingston had finished writing a song. Now, major artists tour without bands, preferring to have a backing track and dancers. We have lost that interplay between musicians on stage and in the studios.

Boyd’s book will have you searching for old Cuban classics, copies of Ravi Shankar albums, music from the Balkans, and reggae. It is an extensive volume; however, each chapter discusses a different genre of music. Even the most well-read music buff would still find plenty to captivate them in each section. Take your time and absorb it. The roots of rhythm may remain, and we hope that will always be true.