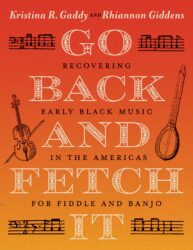

Kristina R. Gaddy is a Swedish-American writer who has researched and written hard-hitting non-fiction books. Notably, “A Most Perilous World: The True Story of the Young Abolitionists and Their Crusade Against Slavery” and “Flowers In The Gutter: The True Story of the Edelweiss Pirates, Teenagers Who Resisted the Nazis.” Collaborating with Rhiannon Giddens, she co-wrote “Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History” She has again joined with Giddens for this latest book. This time, along with the history, the duo have done precisely what it says on the cover and gone back in time to search out the old tunes.

Kristina R. Gaddy is a Swedish-American writer who has researched and written hard-hitting non-fiction books. Notably, “A Most Perilous World: The True Story of the Young Abolitionists and Their Crusade Against Slavery” and “Flowers In The Gutter: The True Story of the Edelweiss Pirates, Teenagers Who Resisted the Nazis.” Collaborating with Rhiannon Giddens, she co-wrote “Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History” She has again joined with Giddens for this latest book. This time, along with the history, the duo have done precisely what it says on the cover and gone back in time to search out the old tunes.

Giddens is well known to AUK readers as part of the trio Carolina Chocolate Drops and a successful solo artist in her own right. The recent documentary “Don’t Get Trouble In Your Mind: The Carolina Chocolate Drops’ Story” touches on some of the ideas and tunes featured in this fine book. In the documentary, Giddens talks about having to search back for the old banjo tunes and playing styles. With this book, you not only get to read about the music and history but also immerse yourself in it by playing the songs.

The book starts with a brief history and discusses other attempts to collect the music. In the wake of the Civil War, three abolitionists attempted to track down written excerpts of the tunes and compiled “Slave Songs of the United States”, a bold introduction and the first collection of Black music in the United States. Lucy McKim Garrison, William Francis Allen and Charles P. Ware wanted to preserve the music and distribute it to the formerly enslaved. Gaddy and Giddens are carrying the torch on and have gone further back to search for the music and transcribe it for others to enjoy.

You don’t need to be able to play the banjo to enjoy this book. The music is collated and explained in a highly readable style. The songs ranging from 1687 through the 1860s are transcribed in modern treble clef and banjo tablature. There is no doubt that these tunes had a profound influence on 19th-century bluegrass, country, roots, and American folk music, which is still evident today.

The book includes a chapter by Giddens specifically explaining how the notations were produced, how to play the songs and the history of the banjo. The documentary mentioned above showed the Carolina Chocolate Drops meeting with old-time fiddle player Joe Thompson. Giddens explains how Thompson was the last of his family to play a type of banjo-led string band in North Carolina. Her style is greatly influenced by sessions playing with Thompson, learning from a master. We could get into a lot of detail here, but suffice to say, the chapter will open your eyes about the possibilities and different banjos there are and how they affect the sounds. It’s a captivating and informative read which tees up the following sections beautifully.

There are nineteen tunes to read about, and the middle section of the volume explains the workings behind three of the most recognisable tunes. The first one, “Pompey Ran Away,” already has versions transcribed, and a quick internet search can render a handful of played adaptations. There is little known about the tune, and the writers describe the tune as a jig; however, “Pompey Ran Away” differs from other jigs as it is 3/4 time rather than 6/8 time. It appears in European collections, proving that the people across the water were taking an interest and wanted to participate in this style of Black music.

“Black Dance” continues the story with excerpts from Dr Christopher Carlander’s diary. Carlander, a Swedish doctor arriving in Saint-Barthélemy in 1788, wrote how he saw a captain called Skånberg dancing with a woman named Queen Christina in what he describes as “a rather ridiculous dance”. By the end of the chapter, Carlander does become a little more tolerant of the inter-racial dances, even noting down the protocol and moves in his diary.

The mysterious “Congo,” written in 6/8 time like a jig, was found in a handwritten music manuscript of the Bolling family. The Bolling family were from central Virginia. We learn that the family owned slaves and made their money from tobacco and other crops. The manuscript includes music composed by members of the Bolling family, so it would not be a revelation to find that they asked enslaved musicians to play with them or for them and to share their playing techniques.

This is a captivating book overall with plenty of interesting facts about the instruments, the people and essentially the tunes. Gaddy, Giddens and their researchers have done a fantastic job tracking down as much information as possible. Included in the book are plenty of drawings and early artwork, giving a feel for the times. Now that it has been fetched, we can all read about it, and those talented ones among us can play it.