Concentrate on what is right and let others know it not on what is wrong à la Bob Johnston.

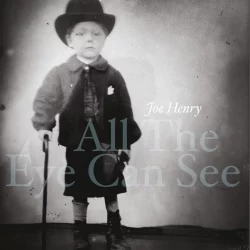

Joe Henry is a bit of an artistic polymath being a successful singer-songwriter and a three-time Grammy Award-winning producer, not to forget to mention, an author. Apart from his own significant body of work where he has collaborated over the years with T Bone Burnett, Daniel Lanois, Van Dyke Parks, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and Bill Frisell among many others, he has worked on records by Bonnie Raitt, Elvis Costello, Solomon Burke, Rhiannon Giddens, Rosanne Cash, The Milk Carton Kids, Billy Bragg, Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, Mose Allison, Allen Toussaint, The Carolina Chocolate Drops, and many more. While there is always a debate about what constitutes americana, there can be no doubt that Joe Henry has proven his ability to capture the true spirit of America through his own musical output and his work with others. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up over Zoom with Joe Henry at his home on the Maine coast to discuss his new record ‘All The Eye Can See’ and his approach to record production. Like many artists, he explains he needed to develop a new approach to working during the pandemic lockdown. While he is known for his eclecticism, he explains that the two artists that started his own need to become a songwriter are Bob Dylan and Randy Newman and that the prime influences on his production career are Bob Johnston and T Bone Burnett. He also shares one of the main highs of his own career, the time when Ornette Coleman agreed to play on one of his records.

You are one of only a handful of artists who have managed to maintain a very successful career as a producer for other artists while being an established and consistent recording artist yourself. What do get personally from each of your careers?

I think it is important to note that I don’t really see a distinction between the two jobs anymore but I used to. I used to think what I did for myself as an artist and what I did for others as a producer were very different pursuits but I don’t think that way anymore, now I see less and less distinction and more shared ground in my working lives. What I think they share is regardless of whether it is my voice or my song or someone else’s, what I really mean to do is get something meaningful to come out of a bunch of speakers. The goal is the same every time I enter a recording studio, and I also know that what I have learnt as a producer working with other people, being in service to others, I’ve been able to bring back to my own work and apply for myself because you see things really differently when you are in service to another than you do when you are only looking after your own needs.

Sometimes producers use creative tension to bring the best out of other artists, how does it work when you are producing yourself?

No, I don’t really believe in the concept of tension between an artist and producer as really being necessarily helpful. It does happen occasionally, but it is pretty rare for me to find myself out of alinement with anybody I’m working with, either musicians who I’m working with on my own records, or artists or bands I’m producing. I’ve been very lucky that way, and I know that sometimes tensions can lead to productive results, but I don’t think you can deliberately create difficulty and expect great art to emerge from it. Any time I’ve witnessed people doing that actively it doesn’t end well.

You are able to bring new things out of artists, where did your eclecticism come from and how do you maintain the right balance between creativity and ending up with a dog’s breakfast?

I’ve always been interested in a lot of different kinds of music, and not only music. My life as a songwriter has been informed by art of every discipline, I have lots of dear friends who are poets, novelists, painters, sculptors, actors, filmmakers, and photographers, and I’ve learned something from all of those disciplines. I tend to think it is eclectic because there is a big wide world out there, and I do know that while all these elements may seem disparate to a point, I’m still having to consider them through my own lens, whatever that is and whatever is uniquely mine. I always think that however eclectic my tastes may be, they will always be filtered back through the same funnel and into the same bottle for consumption. I think things get unified as we place them together, they don’t remain radically different. We can put radically different concepts side by side and feel the tension, but more likely we feel the shared relationship between them.

Your own records tend to be personal, what was behind the songs on ‘All The Eye Can See’?

I think I’m driven by a few of the things that have always driven me as a writer and which have interested me the most are number one, how do we all live robustly in the face of knowing that we won’t always, and that is something I think almost all the characters of my songs are grappling with. Likewise, how are we having community with each other when there are so many things that seem to want to pull us apart, how do we maintain an understanding that there is much more that connects us than separates us? Lastly, I’ve always been interested in how we keep our fears and hopes in balance with each other because they are both seemingly omnipresent.

I assume the current divisions in America are making you a little uneasy.

I’m more than a little uneasy, and on any given day I can tell you I’m angry and disgusted, but on any given day I can say I do remain hopeful because, for as much as what is pulling at the fabric of our country right now and threatening to tear us apart, there are so many more people I believe who are well-meaning, well-intentioned, good-hearted people, who aren’t the loudest and they aren’t the ones with the most money, but I do believe there are more good people than not. That helps me stay buoyant and keep my hope intact, as treacherous as the times do seem, they really do. However, I will let you into a little secret, things have always been treacherous here, we have just been better at hiding it, but the mask is off and I keep reminding myself of that all the time. This country was built on a great hypocrisy, to hold ourselves up as torchbearers of freedom and justice while building the country on the blood of native Americans and on the backs of enslaved peoples. That has always been our truth, and to pretend that things have just all of a sudden have gotten terrible is woefully naïve. Things have always been treacherous and we have always hopefully been walking in halting steps towards better.

How did you record ‘All The Eye Can See’ and why so many musicians?

I’ve historically been an artist and producer who prefers to have all the musicians in the room together playing music in real-time and going for live takes, which is an incredibly exciting way to work, but this record was recorded during the pandemic lockdown so I had to find a new way to work if I wanted to stay active. So, I learned to record myself at home right at the beginning of lockdown and I found it really stimulated my songwriting to be able to immediately record songs, rather than I had in the past, waiting until I had a full album of songs in the boat before I started thinking about how to articulate them. In this case, every time a new song arrived, I would immediately record my part of it, you know the vocal and guitar, and then sending the digital files out one at a time to other musicians. First across town, because I was still living in Los Angeles at the time I was recording much of this record. So I was sending new things across town to my most frequent collaborators, then across the country, and then outside the country, and then I realised so many of my peers and dear friends were sitting at home in lockdown all looking to remain creatively active and connected to each other. When I reached out with a new song and asked if they heard themselves contributing to it, what do you hear yourself doing, people were so generous and so eager to offer something up because it was the way we could stay active and in community with each other.

I’ve historically been an artist and producer who prefers to have all the musicians in the room together playing music in real-time and going for live takes, which is an incredibly exciting way to work, but this record was recorded during the pandemic lockdown so I had to find a new way to work if I wanted to stay active. So, I learned to record myself at home right at the beginning of lockdown and I found it really stimulated my songwriting to be able to immediately record songs, rather than I had in the past, waiting until I had a full album of songs in the boat before I started thinking about how to articulate them. In this case, every time a new song arrived, I would immediately record my part of it, you know the vocal and guitar, and then sending the digital files out one at a time to other musicians. First across town, because I was still living in Los Angeles at the time I was recording much of this record. So I was sending new things across town to my most frequent collaborators, then across the country, and then outside the country, and then I realised so many of my peers and dear friends were sitting at home in lockdown all looking to remain creatively active and connected to each other. When I reached out with a new song and asked if they heard themselves contributing to it, what do you hear yourself doing, people were so generous and so eager to offer something up because it was the way we could stay active and in community with each other.

How prescriptive were you with the other musicians?

I never tell anybody what to play, whether they are in front of me or not, I just play them the song and ask what they hear themselves doing. If anyone is asking for direction I will try to give them some, but it is never my assumption to begin telling somebody what to play because then they can’t hear their own voice, they just hear what I want and then try and give that. I know I can always go back to what I was originally thinking, but what I will never get back to is what a great musician like Marc Ribot or Jay Bellerose or anybody else on this record, what do they hear when someone else told them what to hear? That is one of the things that most interests me, tapping into musicians not just for the instrument they play, but for their personhood, their life experience, and their humanity. That is what I want.

What was the biggest surprise you got when the tracks came back?

I think the biggest surprise was when I approached Daniel Lanois, who I’ve known for decades now, I first had the idea for him to play pedal steel on the first song I sing on the record which is called ‘Song That I Know’ and I sent him the track. He wrote me back later and said he had been playing around with the song and he said he didn’t think he was contributing anything worthwhile to it, but instead he had created two instrumental versions based on my melody and he gave them to me if I’d like to use them. So the instrumental song that opens the record, and stands as the penultimate song in reprise are instrumental songs that Daniel Lanois created based on a melodic song I had written, and I didn’t know that was going to happen, and I didn’t expect that at all but I was delighted when it did.

What is your approach to songwriting, are you very structured or is it a case of waiting for the muse to come?

I try and write something every day, whether it is a song or not, I try and keep that blade sharp in any way I can. I’m a very disciplined writer in that regard, but if there is not a song to be had I don’t torture myself over it because there are so many things that need attending to in a day. If there’s not a song to be written then I will do some laundry, wash some dishes, or start dinner. But I do try to be writing at all times in some way, and I’m always listening for the musicality in whatever I write, even if I’m writing a letter to somebody I’m always awake to a phrase that might grab my ear and strike me as musical and might send me off in a particular direction. But I do try and remain loose and maintain discipline around it.

If asked who was your biggest songwriting influence and your biggest production influence could you answer the question, or are you more of a composite of the artists who have gone before you?

Well both, I’m certainly a product of dozens and dozens, if not hundreds, of musicians who have inspired me, and I became a serious listener of songs when I was seven years old, and the music I cared about then is still music I care about. I’ve always had good taste is what I’m telling you, haha. I would be less than honest if I didn’t share that it was Bob Dylan and Randy Newman, when I was eleven or twelve years old, who first made me think about writing a song of my own, even though I had been deeply invested in songs and wildly moved by them from a very young age. But when I first consciously heard Bob I instinctively felt an invitation there, and I first heard Randy Newman shortly after that and understood from him as well something that galvanised me not just as a listener, but also as someone who also wanted to be a creator. The same is true of Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, and Robert Johnson, and I can spiral out and it could become endless, haha.

As a producer though, it was Bob Johnston, who I think is woefully underappreciated, and I came to learn that as a producer I work very much like he operated even though I didn’t know how he operated, but I do know that those albums that meant so much to me that he was producing in the middle sixties, whether they were Bob Dylan’s records, or Johnny Cash’s records, or Leonard Cohen’s records, or Simon & Garfunkel, his enormous body of work as a producer and the way I’m producing that is most aligned to the way Bob Johnston worked, and something I learned from my career mentor T Bone Burnett, is that idea of not telling anybody what to play, but being a good casting director in as far as who you invite into the room and then just providing love, support and encouragement so that people give you whatever they have, and they do.

You could say that Bob Johnson was so facilitating he was like a none producer.

There is one moment on one of the Bob Dylan Bootleg Series records, I think it is an outtake from ‘Blonde On Blonde’, where they are taking a run at ‘I Will Keep It With Mine’ it sounds like a very early take, everything is loose and not solidified, and at one point Bob Johnston just comes over the talkback mic, speaking to somebody I don’t know who, saying “Yeah, what you were doing”. I thought that is exactly how I work, just walking around the room and I listen to what people are doing and just say, “Yeah, that, more of that”, rather than telling people to stop what they are doing or to try something different. I’m looking for the things that are working rather than those that are not working that well and I’m looking to amplify those. My experience bears out that when those things are amplified good and generous musicians in the room will respond accordingly. If I say to the drummer, and most often it is Jay Bellerose, “I love what you’re playing”, everyone else in the room considers what about Jay is doing is right and thinks if what he is doing is right, then what are they doing in response, how are they going to join that particular parade. When I heard that little moment from Bob Johnston on the talkback with that remark I think I just literally stood up out of my chair and felt so incredibly affirmed, of course, that is what he is going to do, just listen to what’s working and illuminate it. Affirm that player, knowing it will have a reverberating effect in the room on the other musicians.

You’ve learnt the lesson well, haha.

I’ve tried my best, haha, and it is the way that T Bone operates. I don’t know how much T Bone was consciously learning from Bob Johnston, but T Bone loves those records almost as much as I do so it is a lesson not lost on him either.

You’ve worked with an unbelievable number of other musicians over the years, but I have to ask, from a personal point of view, what was it like having the late great Ornette Coleman on one of your records?

It was one of the great nights of my working life because I had been told when I first approached him by writing a letter and initially hearing back from somebody who worked for him that Ornette doesn’t really do that, and he has been asked by everybody but he feels that if he says yes to you after having said no to other people, it is like he is judging their work and he doesn’t want to do that. He wishes you well and you should keep doing what you are doing, he is going to keep doing what he is doing, and I thought that was the end of it, but the same person called me back a few days later and said “I’m really surprised to be calling you, I’ve never made this call before”, and Ornette had listened to my current record I’d sent him, I think it was probably ‘Fuse’ that I sent him, and this person explained the Ornette knew exactly why I wanted to work with him, and he would be delighted. There was no one happier than me, it was one of the most exciting moments I’ve had in the studio, and one of the moments when I have been most honoured by an artist’s participation as I’ve ever been.

Were you intimidated, what did it feel like?

Well of course I was, haha, but he treated me like a peer, which was incredibly humbling for somebody like me. He thought a lot about what his job was because he hadn’t been a sideman to anybody else it wasn’t just something he was doing by rote. The song is a blues in G Minor, he could have done that in his sleep, but he thought long and hard because I could tell, trying to figure out what his real job was, you know, what’s my role here. We talked about it, and he was playing as an overdub the last element we were adding to that song one evening in a studio in New York City, and he played many takes and they were all wonderful and interesting, but for him, he was looking for something very particular, he was looking to observe a real particular character. At one point he said to me at a break, “You know, I’m not doing badly for you but I know the saxophone so well and I can hear I’m still playing the saxophone, and if it is OK with you, I need to keep going until I’m just playing music. I thought that was the most generous thing to offer, both for his time because I was already happy, but also a life lesson that even he, the master that he was at that moment, needed to transcend the delivery system, the articulation machine that the saxophone was and just get to the point where there was nothing standing between his heart and the beating heart of the song. It was really wonderful to be in his company.

That is a really great story, marvellous stuff. Do you have any plans to tour ‘All The Eye Can See’ and will you get to the UK and Europe?

Yeah, we’re making plans right now, and my best plans are that we will be in Europe in the early summer, June perhaps. I’m still working out how many dates I’ll be playing

At AUK, we like to share music with our readers, so can you share which artist, album, or track is currently your go-to listen?

I’m almost embarrassed by how obvious this is, haha, I’m still on my Duke Ellington kick, and on almost any given day he just seems to fit the winter landscape here, and I can’t stop listening, most particularly his album ‘Piano in the Foreground’ and I recommend that to anybody.

He is an artist whose importance just seems to grow with the passing of time.

Our debt to him is one we will never pay off. It was Springsteen who said, “I’ve got debts no honest man can pay”, that’s how I feel about Duke.

Finally, do you want to say anything to our UK and European readers?

Yes, as an American I’m sorry, haha. We are doing the best we can, some of us. I will leave you with one last Ornette story, a couple of months after we recorded together I turned 40, and my wife and children brought me coffee to bed very early on that Saturday morning and the phone rang. I wouldn’t have answered it, but my wife said she was sure it would be my mom and dad and I should answer it. I picked the phone up, and nobody said anything but I heard the phone set down, and then Ornette plays me ‘Happy Birthday’ for two and a half minutes, and it was tremendous and I just had tears pouring down my face. I had so many friends when they heard about it later say to me it was too bad I wasn’t home because I could have recorded it on my answer machine, and I’m thinking how in the world could that be better than me hearing him in real-time.

Thanks for showcasing Joe Henry Martin. His albums are a joy and he is always able to bring out the best in those he works with. Saw him in 2016 with Billy Bragg and the album they made together “Shine a light”, is a stone cold classic.

Thanks, Andy. Yes, he is a fairly unique artist and producer who knows how to find something extra for a performance.