A renowned country guitar picker and producer who likes a bit of Chet, Frank, and Wes on the side.

Pete Anderson was able to bring the right sound to Dwight Yoakam’s voice and songs when they met up in the blue collar country bars of Los Angeles in the ‘80s, and so was born one of the most commercially and artistically successful partnerships in roots American music in the late 20th Century. Born in Detroit, home to Motown, The Stooges and The MC5, and like a lot of musicians of a certain age, Pete Anderson was turned on to the guitar after seeing Elvis Presley on TV, not realising at the time that the guitar sound was all Scotty Moore’s. As well as early rock & roll and James Burton, it was Dylan and the blues that got most of his attention in his formative teenage years, helped no doubt by his dad’s southern heritage. Quite a few artists have benefited from Pete Anderson’s production and guitar skills over the years, and he has a catalogue of his own albums that, not unnaturally, feature his considerable guitar skills. Americana UK’s Martin Johnson caught up with Pete Anderson to review his career and discuss his new book, ‘HOW TO PRODUCE A RECORD: A Player’s Philosophy For Making A Great Record Recording’, which was reviewed by Americana UK here. He also talks about his relationship with Reverend Guitars and his latest model, the Eastsider Custom. Pete Anderson also shares the fact there is some Frank Sinatra, Chet Baker, and Wes Montgomery in his guitar playing and that Montgomery is his favourite guitar player.

How are you, and where are you?

I’m fine, I’m at home in LA, I have a studio in my backyard, and so I’m in my backyard. I just walk out here and go to work and do what I do at my age, potter around.

I’m afraid I’m going to have to ask you a question you will have been asked innumerable times before and are probably sick to death of hearing, so I’m apologising in advance. You grew up in Detroit, home of Motown, Ted Nugent, The Stooges, and The MC5. How did you develop your interest in roots music?

You know, my father was from the South, so when I was a boy, I remember watching the Grand Ole Opry on television, I think it was on on Friday, then shows like ‘The Hit Parade’ and the radio, they played popular music so if it was a country song, or if it was Frank Sinatra, they didn’t discriminate. The charts were literally what was popular. So I heard the music growing up, and like everybody else, as a teenager and at eleven or twelve, when you first start exploring music, I just listened to music that was local to me. There were black blues stations you could listen to, and I remember hearing ‘Born Under A Bad Sign’ by Albert King when it was a hit when it first came out. I heard Muddy Waters on the radio, and that really appealed to me. I also listened to the Motown stuff, I listened to all the popular stuff, but I was attracted to folk blues. I kind of went backwards from the Muddy Waters and Albert King stuff, and around the time I was sixteen, I bought a guitar, and I was inspired by Bob Dylan to play folk music.

The early Dylan stuff was just a goldmine of other artists who had influenced him, and I was the one who would start going backwards. If I listened to a Rolling Stones record album, I would look at all the names on the back of the album and go like Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, who are these guys, so I went backwards and did my own study of the music. Once I started playing, when kids in my neighbourhood were playing The Beatles, I was playing Mississippi John Hurt and bluesy folk music. My first band was a jug band, and I played guitar and harmonica. I guess I was kind of an arty kid, and I just liked that other kind of music.

How did you get together with Dwight Yoakam, and what were the dynamics of that artistically and commercially successful relationship?

We were both playing the country scene here in Los Angeles. I was attracted to the guitar, and I was attracted to country music because it is so guitar heavy in the stuff I consider country music, I would say 95 or 98% is written on guitar. You had Floyd Cramer and Boots Randolph, and then everything else was a guitar. It was exciting to me because it was guitaristic. In the blues, you kind of shared it with the harmonica, the saxophone and the piano, the soloing, which for me was the creative aspect. So I was playing country bars, and I’m nine years older than Dwight, and he was like the new kid on the scene, and he just needed a guitar player. Through a mutual friend, he called me up and said he’d heard I was looking for work. I wasn’t playing with anyone specifically, the phone would ring, and I would go play. We were playing three or four sets a night at blue collar bars playing country music.

That’s how we met, and in those situations, you don’t really do original songs, but Dwight had about twenty songs written by the time I met him. Even before we ever made a record, he had written ‘I Sang Dixie’, which is one of the best country songs ever. He would sprinkle his songs in the set, we would do Bill Monroe, Hank Sr., and Merle Haggard, and then he would do one of his songs, and I got to hear his songs, and I was like, man, these sound like commercial hits that I never knew had been released by somebody else. They were really, really good songs, and that is what attracted me, the depth and the quality of the material he had written.

You had a long relationship, what did you get out of it personally?

I learnt a lot of stuff about the music business along the way, stuff I didn’t know, and what I got out of it was a career as a record producer. I could write songs, but I wasn’t a songwriter, I was a song doctor. I’m a firm believer in water seeking its own level. Left to your own devices, you will find out who you are. In that case, with me, when I’m rested up and twenty-five years old, and I play 9 to 1:30 in the bars, and I just want to play the guitar. I don’t want to write songs, I don’t want to produce records, I don’t want to co-write, I don’t want to arrange, all I want to do is play the guitar. So that was my desire, and everything just stemmed out of my desire to play the guitar. If I was playing guitar, it was like this is a good thing, and I’m happy with it. Then I got into the situation with the band, and I was a little bit of an organiser, so I would try and do an arrangement for the band, listen to records and try and work out how classic songs were arranged, rhythm section arranging specifically.

I did that for Dwight because the songs were not arranged. They were a little bit scattered with verse, chorus, bridge, and solo, but not many bridges because he didn’t have many bridges back then, just guitar riffs. I was coming up with the signature lines to wrap it up in a nice little package. My job was arranging, and Dwight acquiesced to that, so we spent a lot of time playing and arranging his music and, unbeknown to us, getting it into some form of shape to record someday.

Why write a book on how to produce records, ‘HOW TO PRODUCE A RECORD: A Player’s Philosophy For Making A Great Record Recording’, and what made you think it needed to be done?

It is the only book I’ve ever written, and it will probably be the only book I will ever write. That said, I’ve watched people write books over the years, and they always have this answer of wanting people to experience what they have experienced or they think it will help people. My book will help people, but I had this information stuck in my head for years, and I had done interviews and seminars and talked about record production to the point where I had it chronologically arranged in my head. I wanted to get it out of my head and onto a piece of paper so that in itself was like, maybe this could be a successful book, and to be honest, though it is small and started off small, it could be a stream of income. So, to be honest I’d be happy to make a stream of income from the book. Also, I looked around to see if there was a book with the same perspective that I wrote it from, and I couldn’t find one, so I felt pretty good about the space it was going to be in because I’m a musician producer.

It is the only book I’ve ever written, and it will probably be the only book I will ever write. That said, I’ve watched people write books over the years, and they always have this answer of wanting people to experience what they have experienced or they think it will help people. My book will help people, but I had this information stuck in my head for years, and I had done interviews and seminars and talked about record production to the point where I had it chronologically arranged in my head. I wanted to get it out of my head and onto a piece of paper so that in itself was like, maybe this could be a successful book, and to be honest, though it is small and started off small, it could be a stream of income. So, to be honest I’d be happy to make a stream of income from the book. Also, I looked around to see if there was a book with the same perspective that I wrote it from, and I couldn’t find one, so I felt pretty good about the space it was going to be in because I’m a musician producer.

So, if you and I were going to music school and we were studying guitar, and they put a flyer up on the billboard saying they are going to start a record producer class, and if we went, that’s pretty cool, we want to record our own songs and make our own records, which is easier today than it has ever been. If we went to the class and the first thing the teacher started talking about was decibels, sound levels, and input lines, I would look at you, and I’d be out of there because that technical stuff is not for me. There is much more to producing a record, it is not engineering a record, an engineer can be a mechanic, but a producer is much more of a creative chair. I don’t think you can be a producer and be a mechanic. You have to have an artistic flair and an understanding of the human condition, it is very much like being a director of a film, and the same parallels are there. I think the name producer is wrong, they should call you a director, but it operates the same way as a director of a film. So you have a lot of things the artist is counting on you to assist them with or to do.

I was very impressed with how ‘HOW TO PRODUCE A RECORD: A Player’s Philosophy For Making A Great Record Recording’ looks. How did you determine the structure of the book which is very logical, it has some great illustrations, and the presentation is not dauntingly technical.

I’m very happy with the book, and we worked really hard on it. I had Mike Molenda, editor of Guitar Player magazine for twenty years, he worked on editing it, and he did a great job. It is a logical layout, and it is more about how to get yourself organised to make your music presentable, and it is not designed to be technical in any way. I wanted it to be on the artistic side, so it is basically a step-by-step guide on how you can organise yourself, and you can break any of these rules if you want. You can say I’m going to do Chapter 4 before I do Chapter 2, but if you do that, you could run into a problem down the line, but it is not rigid. It is not like putting together a model aeroplane it is a concept and philosophy, and it is solving problems in a logical order that I’ve experienced through making a hundred records.

Did you have any concerns about demystifying the role of the producer with the book?

No, no, not at all. There are other producers like me, and there are engineers who become producers because they have some musical skill, and there is the supreme example of John Hammond Sr., who wasn’t a musician and wasn’t an engineer, he was a musicologist. He had studied music and all the records, and he could talk to you about Charlie Christian’s solo with Benny Goodman, he could gain the respect of the musicians, he was a tastemaker. Then there is the musician producer, which I am, and there are plenty more musician producers. I have no desire to touch the board, I don’t want to plug in a microphone, I don’t want to grab a guitar cable, I don’t want to do any of that stuff because it has no interest for me, I’m looking at it from an entirely different perspective, more like a painting.

You’ve mentioned John Hammond Sr., but who else are your favourite producers, the ones you have admired the most?

That’s an interesting question, I’ve never been asked that question, so credit to you for asking me a new question after all these years. That said, I will answer it like a politician where I don’t answer it, but you will get the gist of it. I sympathise with anybody who has to hire a producer, any artist who has to hire a producer I sympathise with because how do they know what I did and how do they know what I do? I don’t want my records to sound the same, so they can’t go, I like the sound of his records because there shouldn’t be a sound to my records, they should all be individual pieces of art that I helped somebody create. If you could watch me from when I came into the studio until I went home on some days, you might see me save a song by doing something different, on other days, the most you may see me do is order lunch. So, an artist doesn’t know what I did so how does he know how to hire me. Part of it is personality, so they’ve got to like your personality and work ethic, so in choosing my favourite producer I don’t have one, I have favourite eras of music, I have favourite sounds of studios like Chess records, the Sun records, Muscle Shoals records, the Motown records. I could learn from them, I could emulate them, but I didn’t want to recreate them because, unfortunately, they were all dated, and I wouldn’t have been doing a service to the artist, I would have been doing a service to a dated piece of product which is not what I want to do.

It may be an unfair question, but which of your own productions are you most proud of?

To be honest, I think I did a good job on all of them, I’m not unhappy with any record I’ve made, and I try and exceed myself every time I make a record. It is like this one is going to be a little bit better, or I tried to learn something, but I must say the record I made with Michelle Shocked called ‘Short Sharp Shocked’ which was the first record I made with her, is a pretty magical record. It was made pretty fast because she was prepared, and we didn’t have band cuts on every song, the record fell together, and it had a spirit. It is probably my favourite record of all time because of the way it was made and, the way it came together, the glue that it had. The record ‘This Time’ by Dwight was a technical achievement because Pro Tools had just started, and I was learning how to use it as a musical tool and not as the rule. ‘This Time’, that is a big-time record with some epic songs, ‘Fast As You’ and ‘A Thousand Miles From Nowhere’, and it is pretty hard to beat even today, as I listen to it. So I would pick those two.

You mentioned digital recording, how easy was it to adapt to it and do you have any regrets?

I have no regrets. That would be like asking me if I regretted not using my candles to read tonight because you turned on an electric light. The thing about Pro Tools is that I had to understand it because I’m not that technical, I could barely get the Zoom call on today. I had to realise the power of it and what it could do, and once I did, I was overjoyed because everything Pro Tools does is the stuff that I and other producers and engineers were doing anyway. But it was so much more time-consuming. You would get a piece of tape, make a loop, and have a guy stand across the room with a pencil, dial it in and cut the tape, and you’d get a harmoniser box and hook it up to a fader and try and pitch correct the vocal. You would take a mandolin fill from the first verse and put it on some tape, and try and fly it into the second verse.

All of this stuff was being done, but it wasn’t push button, so once we entered the digital world, it was like going through a closet of jewels and gold. I remember doing the Sara Evans record, and we had Pro Tools, and I was using it to the side, I wasn’t using it as a studio; I was using it as an effect, and she was singing out of tune, and I asked the engineer if there was something in the box that could change the pitch, and he told me there was a pitch correct program for vocalists. I told him to go get it right now, why are we torturing ourselves? So I’ve got no complaints, and everything in Pro Tools I’ve AV’d it to my ears, and if it passes my test, I’m happy with it.

You see yourself as primarily a guitarist, what is your relationship with Reverend Guitars?

When I left Dwight, I started working with an artist on my own label called Moot Davis. Dwight’s music was Bakersfield, triads, and early California country, Merle and Buck, and a telecaster and that whole family fits together. The next guy I worked with after Dwight was Moot Davis, and I toured with him and was in his band, he was much more in the late ‘50s, Webb Pierce, Hank Sr., and they had complex chords, they weren’t triads any more, there would be six chords, diminished chords, augmented chords, things of that nature. There wasn’t a lot, but enough, and my telecaster didn’t sound right because it wasn’t a prominent guitar in the ‘50s, it was more about big-bodied Gibsons.

I didn’t have a good guitar of that nature, and I started playing one Epiphone gave me, and it really was a truck, it was a brick of a guitar with not much sustain, but it was the right sound. So I started searching, and I thought, I’m Pete Anderson, I should be playing a better guitar than this, so I was looking for someone to make me a guitar with the properties I wanted. I went to Gibson, I went to Epiphone, I went to a builder in Quebec, and I went around in circles, and I couldn’t get anywhere, and Rick Vito is a friend of mine, and he had a signature guitar with Reverend that was a solid body and had nothing to do with what I was trying to do, but I called him up. He told me that these guys were pretty cool and that I should give them a call.

Here’s the funny thing, they are in Ohio now, but the shop they started the company in is on the corner of the street I grew up on. If I went out the front door of their shop and did a left and a right and walked down the block for four blocks, that’s my house. I knew exactly where they were, exactly where the building was, and we had a fun day at a NAMM Show of twenty questions when I discovered where they were. When you call a company like that, Ken Haas and Joe Naylor are the prominent people, and Ken Haas owns the company and is a marketing guy, I talk to the boss. When I talked to somebody at Gibson, I had to go through layers of people, I didn’t talk to the boss, but when I call Reverend and talk to Ken Haas, I’m talking to the boss, and when I say, “Hey Ken, I want a purple guitar with flashing lights on it.” He might think about it and then go, “Let’s do that, I’ll make a prototype and send it over.” it is that simple. They are super easy to work with, and we have had a very successful relationship, and I use the guitars all the time. I do have some nice vintage instruments I like, but I do use their guitars. When I started off as a teenager buying a Gibson acoustic, I never thought that down the line, I would be designing a guitar I wanted to play and being really happy about it. So, it is pretty much a blessing to be able to call him up and tell him I need this, or I need that, or I’ve got an idea for this type of guitar.

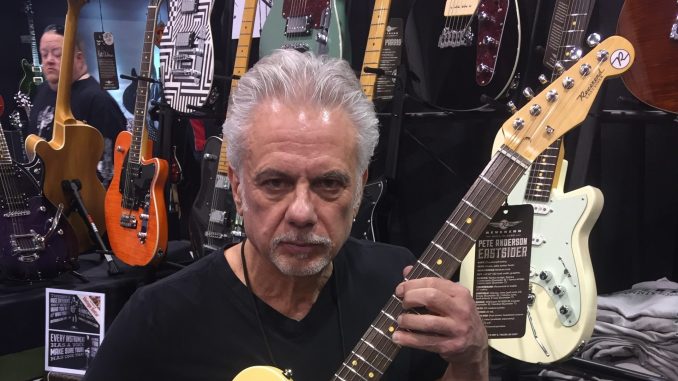

We’ve just put out a new guitar which we announced at the NAMM Show, and I requested it cosmetically, structurally, and technically, and it is called the Eastsider Custom, and I’m very happy with it. That came out in April, and I’m a happy camper. I’ve got guitars coming out of my eyeballs.

Another obvious question I’ve got to ask is, who are your guitar heroes?

Oddly enough, the thing that attracted me to the guitar was seeing Elvis Presley on television when I was a kid. It was such a phenomenon, I think it was 1956, and we had like three radio stations and three television stations. There wasn’t a lot of media, and Elvis Presley’s impact was like a comet hitting the Earth, it was gigantic. I saw him on television holding a guitar, but the sound was Scotty Moore, so I was, unbeknownst to me, attracted to Scotty Moore’s guitar playing, but I didn’t know the difference because I was just a little boy. So I think Scotty planted the first seed that made me go, Man, I love the sound of the guitar, but I associated the sound of the guitar with Elvis Presley. I was like, that man is cool, Man, and he’s got a guitar because I knew I wasn’t going to be a singer per se, but I could jump around and hold a guitar, and I thought that was a pretty good job to have.

Then as I got a little bit older, James Burton came into play, and I was a big-time, big-time B. B. King fan when I came into my teenage years when I started playing a lot of blues. I didn’t start playing country music until I was 21 or 22 when ‘Sweetheart of the Rodeo’ came out, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Taj Mahal, because they were my peers. I wasn’t savvy enough to be looking at Buck Owens and Merle Haggard at the time, I was looking at the young rock guys who were trying to play country music, of course, when I read about it, I went backwards on the records to find out who everybody else was. Wes Montgomery as an adult, hearing Wes Montgomery was it, he is my favourite guitar player of all time. So I guess Scotty Moore, James Burton, B. B. King, and Wes Montgomery are my favourite guitar players, a pretty good group.

At AUK, we like to share music with our readers, so can you share which artists or tracks are currently top three on your personal playlist?

I don’t know if people will get a kick out of listening to it, but I’ve been watching a documentary called ‘Let’s Get Lost’ about Chet Baker. Actually, the first time I came to England, I was so glad Dwight’s bass player, J. D. Foster, begged me to go with him to Ronnie Scott’s to see Chet Baker, and that was just before he died. It was amazing, and I didn’t know who he was per se, I’d heard of him, but I didn’t have any of his records. So I love Chet Baker, and if you are going to ask how a guy who plays country guitar loves Chet Baker, I love his pitch, I love his performance, I love his composition, and I love where he puts the note, it is amazing. I’ve been watching ‘Let’s Get Lock’ and listening to Chet for thirty years.

Frank Sinatra, his greatest hits record had the best versions of his songs, which seeped into my songs because of the way it swings, the way it moves across the bar line, the way the horns move, the horn arrangements, his vocal, the way he phrased because he didn’t sing on one, he waited. It is called late singing, Muddy Waters called it echo singing, he was always singing on the back part of the bar. So those are my big hit guys, I wish there was somebody super popular who I was excited about, but popular music has got so categorised that if you look at one of those satellite music stations, there are so many different genres of music it’s hard to sit down on one and explore it. So, I listen to dead guys.

Finally, do you want to say anything to our readers?

Thanks for saving our music and putting a light on it and saying to America, “Hey guys, this stuff is pretty good, you might want to reconsider listening to this music”. Every time I’ve come to the UK, the shows have been amazing. It is sort of like Mother Earth, the first time I came to England, my thoughts were this is the homeland of Anglo-Saxons, this is where it all started for Anglos in America. So, I appreciate it.