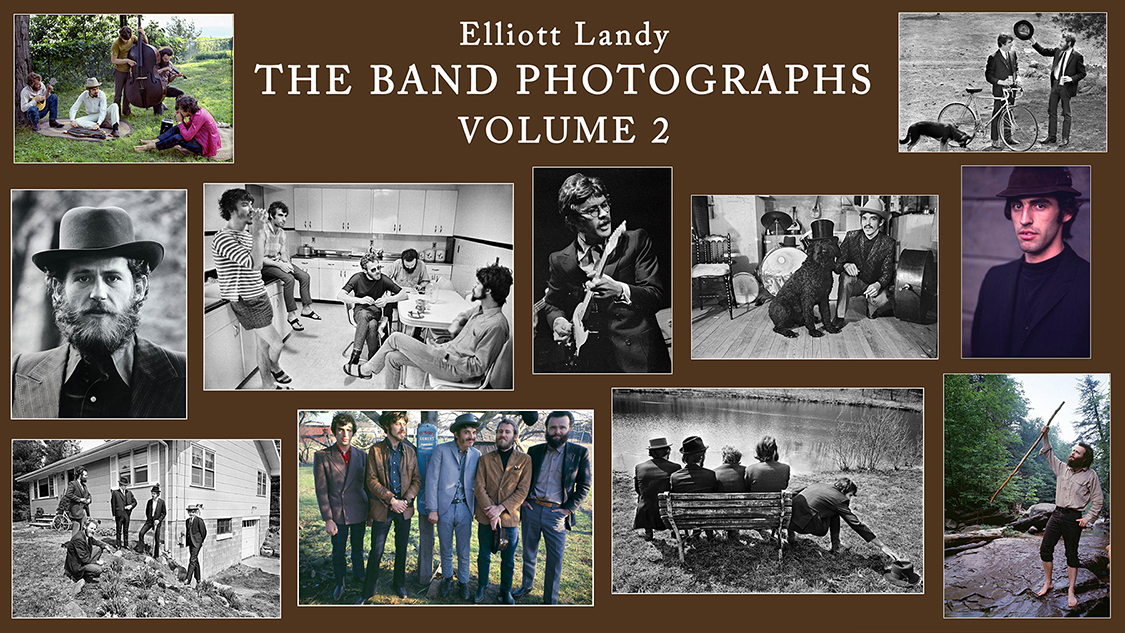

Capturing images of a unique group of musicians as they created their own genre of music.

Elliott Landy is the photographer who will be forever associated with Woodstock. One of the first music photographers to be recognised for his art, he is associated with some of the most iconic photos of the biggest acts of the 60s and early 70s. In particular, he is known for his photos of Dylan and his group of backing musicians that came to be known as The Band. In 2016 he published a volume of his photos of The Band, ‘The Band Photographs 1968–1969’. Funded by a Kickstarter campaign, it became the highest funded photographic book in Kickstarter history. Now he’s back with a new Kickstarter campaign to fund the production of a second volume of photographs from the same period. Photos that he hadn’t realised he still had until he discovered some stray boxes in his studio. The Kickstarter campaign closes on the 7th April and all information can be found here.

I know you’ve been asked this many times, but I’m going to ask it again anyway. How did you get into all this in the first place? You didn’t set out to be a music photographer, did you. Didn’t you want to, originally, do more reportage.

Yeah. So it was 1967 and I wanted to do something to help stop the Vietnam War. And my first thought was I’ll go to Vietnam, take pictures and show how bad war is. And my second thought is, I don’t want to be killed. I don’t want to be in a war. So I got the idea to photograph the peace demonstrations that were going on in New York City. And very often there would be a demonstration in Manhattan that was a fair size, and the New York Times would give it two inches in the middle of the newspaper and without any pictures at all. So, basically, there was no significant coverage of it or what the demonstrators were saying about the war. So, I started to do that. And the mainstream media was not interested in photographs of peace demonstrations, it got very little coverage. I went to the so-called underground newspapers and there was one called the New York Free Press, and another one was called The Rat. And I began working as a photo editor for The Rat. We photographed peace demonstrations and abortion rights demonstrations. And one evening when I had gotten finished with the paper, the office was on Seventh Street, off Second Avenue. I was walking along Second Avenue and I see a theater marquee that says, Country Joe and the Fish with Light Show. And I thought, what is that? What is Country Joe and the Fish? And what is the light show? But I had no idea really. So, I went over to the box office and I heard this incredible music coming out of the theater.

I showed the lady my press pass and she let me inside. And I’m met by this incredible wall of light and audio that goes with it. And it was a mind-boggling experience, those light shows were different, very different to what we have today. Today we have video shows which are made so that they synchronize exactly with the music at exactly the right moment. And it’s certainly very nice. However, a light show then is four or five people behind the stage, each one doing their own thing. Basically, they’re visual musicians and sometimes what they do is great and sometimes it doesn’t work. And the improvisational aspect of it is what makes it superb because there’s highs and there’s lows in your experience of it. It’s not all exactly on the same train route, so to speak.

I saw some of the early Pink Floyd gigs where they had a guy doing a kind of interpretive light show with their music.

Interpretive is a good word for it. I like that. Yeah. Yeah. And the light shows I was watching was the Joshua Light Show, for the most part, they were like four or five people who have different visual instruments. For instance, you put colored oils and colored water together and then you smash them in time to the music. And you had all kinds of weird and lovely shapes and everything and colors. And then another person would have a movie projector and another person would have a slide projector and another person would be showing news clippings from an overhead projector and so on. So, everything was mixed up and all rhythmically connected to the music. Anyway, so after the show was over, I was able to go backstage because I had cameras around my neck. I was obviously a photographer. I got into the dressing room with Country Joe and the Fish, and also Ed Sanders from the Fugs was there just hanging out to say hi. And Linda Eastman was there before she married Paul McCartney. And when I photograph, I’m very careful to be invisible. I’m very careful. I don’t want to be one of the guys with the band. I don’t want to be one of the people they know. I want to be a person just photographing, sharing what’s happening there. And so they let me stay. It was very nice, though I didn’t get friendly with them at all. I don’t even know if I talked to them, that’s not what I wanted to do. I just wanted to show what they were doing. And then two weeks later, this was a theater called the Anderson Theater, two weeks later, the next band was Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janice Joplin.

So that was, as you can imagine, mind-boggling. And I went backstage again, and I was able to take whatever pictures I wanted. I did get friendly with them at this point, I guess they reached out to me. Cause I’m not a very assertive person. If someone doesn’t talk to me, I don’t go over and talk to them usually; even now it’s like that. So, I got friendly with them and that led to going with them to Detroit to photograph them doing a gig at the Grande Ballroom. This was when Big Brother and the Holding Company had been signed to CBS, to Columbia Records, and their manager was Albert Grossman. And Albert also managed Bob Dylan. And he managed Richie Havens and Peter Paul and Mary. I had had a run in with him in Carnegie Hall, this was before the country Joe thing happened, and he actually threw me out of Carnegie Hall, not physically and all that, it’s a long story. If you’re interested you can read about it in my book ‘Woodstock Vision, the Spirit of a Generation’. That’s been published for a while now. You can get it on Amazon, or you can get it from my website. Anyway, in the book, I tell the story of Albert Grossman and Carnegie Hall and the Woody Guthrie Memorial concert. As a result, Albert had a distinct dislike for me.

Well, on this occasion I was photographing Big Brother & the Holding Company in New York City in a concert hall called Club Generation, it was downstairs in a basement. Club Generation later became Jimmy Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland Studio. So, I was there photographing them, and I feel a tap on my shoulder. It was very crowded; you can’t hear anything. It’s got a low ceiling with fully amplified music playing. And Albert goes like this to me, waving me to come back with him. And I didn’t know if he was going to throw me out of the concert or what. I really had no idea. And he takes me into a utility room so we could talk to each other. And he says to me, “are you doing anything this weekend?” And I said, no, I don’t think so. Why? He said, “well, we have a new group and we need some pictures”. And I said, what’s their name? He says, “we don’t have a name yet. We’re thinking about The Crackers maybe. Or maybe they wouldn’t even have a name because they don’t want to be pigeonholed into doing the same music all the time. They want to be free to do something completely different than people who know about them would expect them to do”. So, he said, they may not even have a name, but anyway, if you can go to Toronto next weekend and blah blah blah. They’ll pay for the trip and everything and you take some pictures. And he said, “and Bob Dylan might be there”, just like that. And I said, Okay. And what it was; it was to take the next of kin photographs that were in “Music from Big Pink”. The guys from the band, when they were doing the music from Big Pink album, they wanted to talk back to the Hippie generation. Now the hippie generation was a wonderful, astounding life space to be part of. And I really cherish everything I got from being fully active during that time period, but one thing that a lot of young people were doing is they were rejecting their parents. They were rejecting their relatives. They’re saying, you were part of the war, your culture that’s creating all this war that we have, the pollution and everything that we began knowing about in those years. So the kids were saying, we’re disowning our parents and we don’t want anything to do with them anymore. And the guys in The Band said, “Hey, they’ve brought us up. They helped us be who we are today. They educated us, they love us, they’ll do anything for us and we should be honoring our parents, not dismissing them, not dissing them for the failures of a society” and so on.

So that’s why they wanted a picture of their relatives, their next of kin, in the album to make that statement. And of course, it’s a very powerful and correct statement. That was what they were about then. So I went up there and I just got along with them really well, they’re easy guys to get along with. And then they asked me to go to Woodstock a week or so later and take photographs there. And that’s how I got into it. It was just kind of a chance thing because I was, by chance walking on Second Avenue, and I saw that concert and then I photographed Janice and I showed them the pictures, and one thing led to another.

One thing I should say about this – when I was photographing, and this is the most important thing for me, I was really into photographing to try and help change the world, help the world be better, help society be better like that. And when I was showing my photographs of these musicians, Janice Chaplin and The Fugs and Frank Zappa, Jimmy Hendrix etc, I was sharing and I was sharing a culture, hoping to bring young people down to experience this new culture where you thought differently from the mainstream, and you acted differently from the mainstream culture. You were free to smoke grass, you were free to have sex, you’re free to say what you wanted to say. You tried to find a way of supporting yourself that was in harmony with your inner being and with what you felt you wanted to do in your life; not just go out and get a job and separate your job completely from what your family life was. For me, I was proselytizing with those photographs. I was saying, “Hey, come on down and see Janice Joplin and Jimmy Hendrix and just have these great experiences”. I wasn’t promoting individual artists, I was promoting a great experience. You get stoned, and you hear this wonderful music, and you find another life space to be part of. For me, it was really a political statement; I was never a music photographer. I never wanted to document musicians per se. I just kind of, I tripped into it, I guess you’d say. I accidentally fell into it.

But, as a result, you became one of the leading chroniclers of the Woodstock generation. I mean not just the festival itself, but that whole kind of artistic movement that grew up around the town of Woodstock. Were you aware at the time that it was something special? That it was something that was going to last for a long time? Your pictures document a great period in history that still resonates today.

Thank you. I never thought about the future. I never thought I did anything special. However, I did save my photographs, and you know what? I almost didn’t save them. That’s how little I thought about it at the time. But I did take good care of them, I was a pro and very good technically, so none of my prints are yellow and my film is all still existing properly. I did reach a point where I was tired of photographing musicians and music and peace demonstrations and I stopped taking pictures for a while. I realized, looking back that it’s because I never thought of myself as an artist. Of course, I came to realise that I do create art, and the priority thing about art is that it’s new, that it’s different, that it hasn’t been done before. Anything else, whether it’s beautiful or not, is besides the point, it’s important that you’re not copying something. For me, I had explored the artistic space of peace demonstration, I’d explored demonstration photography and music photography. And I was just tired of it. I just was not inspired to do it anymore.

I realize now how deeply rooted my love of art is, of expressing something beautiful in a physical form. I’ll call that art. And I see that because, at that time, it wasn’t an art for me anymore. I was copying myself, so to speak. It didn’t excite me.

I was wondering why you didn’t continue to take photos of musicians. You obviously had a feel for getting great music-related pictures and yet it didn’t hold you long-term.

Well, I just wasn’t interested in the results anymore. As I say, I’d seen plenty of photographs of musicians at microphones and people just hanging around backstage. It didn’t interest me anymore. Then my wife got pregnant and I found my new medium, I wanted to share the beauty of women, of children, of mother and baby, and the beautiful nest of raising children. We travelled around Europe in an old passenger bus and I photographed my own family, my wife and two children for the next seven, eight years. That’s all I did. my goal then was to share the beauty of children, the innocence of children, and the beauty of mother and child. And the message was to people to pay attention to what’s at home, your family, what your family is about, and the connection there more so than your business. Your business is what you have to do, but focus on your personal relationship and just look at how beautiful life is. That’s really what I was saying by showing these pictures of them. So that was my next phase. Again, I was proselytizing, but for another level of experience.

When did The Band and your connection to them come back into your life? Did your connection with The Band ever really cease? As a result of those early photos you took, your name is always connected to this group of musicians.

Yeah. Well, after I was through with the peace demonstration and music period of my life, I just wanted to leave American culture as it was then. That’s why we decided to go to Europe. And when I left, I left everything here and I left it with Magnum, the photo agency, because they represented my photographs at the time. I didn’t want to be part of photojournalism anymore. I wanted to be part of my journalism. I was moved to take the photos I wanted to take and not do assignments for other people. Anyway, I left some negatives with Magnum and also with a photography lab in the city that I used. But I didn’t see how valuable they were. I’m not speaking in monetary terms, but I mean culturally valuable. They were just something I did, and I didn’t want to throw them away. When I came back from travelling, Larry Hoppen, who was with the band Orleans, at some point he said to me, about my pictures of The Band, he said, “don’t you realize what they are, these pictures? You’ve given them their image. You’ve created this incredible image which talks about American culture and American history and its musical roots and so on. And you really made them who they were. You gave the vision and your pictures are really important”. Somehow that conversation woke me up to the value of what I had done, the historical value of what I had done.

! was totally into my new work, the photographs of my children and my wife and I would hand colour them. And it was gorgeous work, really gorgeous work. And that’s all I was interested in, trying to sell and publish those photos, and Larry said, Hey, don’t forget about this other stuff; that’s when I realized that I still loved the pictures and I got back into working with them. I print them now and I sell prints and it’s a source of income. If I didn’t like the work, I wouldn’t do it. I spend a lot of time making my prints now from that period. I care about the beauty of each print that I make, and I spend whatever time it takes to get it right and get the color or the black and white tones correct and all that.

I just really love to take pictures and I came to realize that I wanted to do a book. I looked over my Band photographs and I saw there were a lot of incredible photographs there. And I wanted to put out a book of my photographs of The Band. So I finally, I did a Kickstarter for that in 2014. It did really well.

That’s something of an understatement, wasn’t it the most successful Kickstarter campaign of its type?

For Music Photography books. Yeah, yeah.

Why did you decide to go via Kickstarter? I would’ve thought that you’d have no difficulty getting a publisher to handle a book like that.

That’s interesting. I had an agent, and I had two offers to do the book. One company even made a mock-up of the book. They actually laid out the book before talking to me. They did what they wanted to do, and they made some weird shaped book where all the pictures were cropped. They were a very big company and one I knew could get a lot of circulation and, probably, a lot of sales. Of course, their sales manager was a fan of the band. But the book wasn’t right. And I thought, well, I’ll do it. The book had to be right. For me, that’s a really important thing. I feel that I’m kind of feeding people food for their essence. Something that helps, that brings people up. I get that feedback a lot now from people. They say, your pictures have always made me feel good, and I really appreciate them. Now I see that the path I’ve chosen, to be pure with my imagery, has really paid off in terms of giving something to people that’s precious to them, which is what my goal always was in photography; to share something beautiful that I knew.

I was going to go along with this, to me, poorly laid out book. It was okay, it wasn’t bad. It was with a very high-level book publisher, St. Martin’s Press, with very skilled designers and everything like that. But I didn’t like it. And I didn’t think it presented the essence of what my work was. Well, originally, I said, okay, I’ll do it. And my thought was that a few years later, I’d do my own book. But the contract they gave me would not have allowed that. I won’t get into the business aspect of it, but they could have stretched out ownership of the rights for many years, without my being able to use the pictures in any other way, so I turned that down. And then there was another company called Abrams, also a really very prestigious photographic book publishing company. And the main guy in the company was a fan of my work. And was a fan of The Band. He brought me into the editorial meeting and I met the editor-in-chief and then the editor that was going to be in charge of my book. And they both were very effusive. “We love your stuff” and very, very nice like that. And then I told them what my vision of the book was and I sensed, as I was talking, they weren’t listening anymore. In the end, we decided not to do the book because I had a way I wanted to do it and they didn’t want to do that.

I realized I had to do it myself. That’s why I turned to Kickstarter. And I got enough money to do it exactly the way I wanted. I did something called a Wet Proof, which is much more expensive than the normal way you proof a book. I chose my own publisher, I chose my own paper. I picked out the book size. The way I got the size of the book, I like to see pictures next to each other and I wanted to see what size page is best for that. I made dummies like full size. I have a large format printer, so, I printed a 20 inch wide sheet with two pictures that would be laid out on 10 inches. I made 10 and a half inches. I made 11 inches a page. I made 11 and a half inches a page, and I made 12 inches a page. And I took these double sided cheeks and I folded them. I made believe they were the book. And I sat in a chair, an easy chair, and I put it in my lap as if I was reading a big book like that. And what came to me, the best size to have it would be 12 by 12 inch pages. So that’s what I chose to make the book. And I realized later on that 12 by 12 inches was the size of an LP album. And it was, to me, the best size. That’s why I was so happy I’d used Kickstarter; first of all, I made a lot more money than I would have through a standard publishing deal, and I had total creative control, total editorial control. And I’m really proud of that book. I don’t mean ego proud. I mean, this is a book that I wanted to share with people. I don’t apologize for it.

I don’t think you should. It’s your art. It’s about seeing it presented properly.

That’s it. I love it when people can do things better than I can. If they had shown me a terrific layout or whatever, I’d have said, wow, thank you. Cause I have other things to do. It wasn’t that I wanted to get into designing a book, but I had to do it in order to present the photographs there. And also, I see I was protected, let’s call it, by life, from making those other deals with those other publishers, which I would’ve done because I hadn’t got a lot of recognition in my life. Now it’s getting a little more, it’s gotten better since I did the book. But it is helpful to be in the hands of a large publisher, they’ve got the distribution, they have the bookstores, the work’s going to get around a lot more than it did get around when I did it myself, because I did it myself, we didn’t sell that many books. It sold out for what it was, but what was it? Around 8,000 books, which was a decent amount for a photographic book. I was willing to go with a publisher just to get the recognition, so to speak, for the marketplace to accept my book. But I wasn’t allowed to do that. The universe is saying to me, Hey, you got to be pure and you got to do it right. It kind of forced me to do it myself. And I’m so happy that I did it even though it was a huge amount of work.

Why have you decided to do a second book now and what are we going to see in the second book that wasn’t in the first one?

Well, I’ll answer the end of that question first. You’re going to see fabulous pictures that you haven’t seen before, because I never published them. I don’t even remember seeing them myself. And I see them now 40, 50 years later. I say, oh, I remember that. But I never made a print of it. I never published it. But I did look at every piece of film I ever shot. I looked at it, with a magnifying glass that you use to look at contact sheets and it’s very painstaking. But I had a good back in those days so I could bend over and it wasn’t painful. But though you’re going to see new pictures that I think are really beautiful; the reason I’m doing a second book, I did not expect to do a second book of my photographs of the band but, maybe a year or two after the first book was finished, I looked at some boxes that were tucked away in the back of my shelves that said, Band photographs, second Band book outs, Band book thirds. Because my process of making a book is to make eight by 10, eight by 11 prints, small prints and printing them next to each other and seeing, do they work as a pair? Laying it out first like that, but with real-size photographs. So I had all these boxes of print, maybe six boxes of photographic prints. With the first book, I did whatever I needed to do. I made three or four hundred prints as proof prints. So I’d see what I was going to do. So I saw these boxes there and I opened them up and I was seeing print after print that I couldn’t believe had not been included in the first book because some of them were amongst my favorite photographs. I said, wow, how can I have left out this picture from that book, and then there were other pictures that I had never even considered printing before that I found. So, that was how the second book idea was born. I had had that idea for a few years, but the pandemic stopped me from working on it. I couldn’t have people in the studio to help me with it and so on. But that’s why we have a second book because the pictures deserve a second book. I’m doing it because I want this work to exist forever. And you make it exist forever. Not only with the paper book these days, but then with an electronic book following that. So anyone in the future can look at a photograph and get the feeling that I was feeling while I was taking it. The feeling that was there, what these guys were about. These really beautiful human beings that I knew. They were all spectacular people.

Why do you think there’s been such an enduring interest in them? They haven’t worked as a band for a long time now, but the interest is still there.

Because their music was so unique. It came out in the middle of psychedelia, first of all. And it was real. It was connected to what the United States was about. You felt the grittiness of it and you felt the purity of it. It was very simple. You heard every word and every song and what they were writing about, what Robbie wrote about. And the other guys, when they wrote some of the songs also, they were writing about everyday experiences that you could have living in this country. And the style of music was completely different. They called it Americana. They created the genre that is known as Americana now. Plus they were fabulous musicians and fabulous singers. So that’s why they are one of the greatest bands ever. I mean, at the time, Eric Clapton wanted to quit cream to try and play with the band.

I can’t think of a band that better represents Americana than The Band, it was what they were all about – the roots of American music and the storytelling that goes with that.

Thank you. They’re totally unique. There’s nothing close to them. Some bands try and imitate them here and there, but nothing close to them. And the music is fabulous. It’s real, it’s eternal. It’s not country, it’s not folk, it’s not rock and roll, it’s their own kind of music. It’s just so unique and it is so good. So that’s why they’re still known. And also, they were very special. And that’s when I want others to see, that as people, they were very special.

When I’m taking pictures, I stay away, I do not want to interview anybody. I don’t want them to explain things to me. I just want to be the fly on the wall that’s taking the pictures to share what they are about. And because I was like that, they were comfortable with me being there as much as I wanted to be there because I didn’t change anything. It wasn’t like Elliot’s here so we have to watch out or we have to do this or that. It was, “Elliot’s here, where is he?” Kind of thing. So Rick and Levon said that anytime I wanted to, I could just come over and sleep on their couch if I was up in Woodstock. I was living in New York City at the time, so I was able just to hang out and just take real pictures. We were in Woodstock, where we were walking around town. I remember this one incident really clearly. We passed this guy and they stopped to talk to him. And they were so respectful. They were so, oh, how you doing? And nice to see you, and really respectful. And I had no idea who he was. Turned out that he was a clerk in the grocery store, where they went to buy their food. And that’s what was so beautiful about them. They respected humanity, they respected human beings, human dignity. And they were gracious too, I never saw them insult people personally. Never. They were just really sweet people. And that’s important to me, to also focus on that kind of a personality, that way to be with people. That’s really a major reason why I liked daring this work still and why it’s meaningful to me, talking to pure artists.

Did you ever get a chance to photograph any of them in more recent years?

Yes. After Robbie left the band, they continued to play and they asked me to do publicity photographs for them; just to come along every so often to take pictures. So I do have quite a few different pictures from other periods of The Band. Maybe that’s the third book. We could call it ‘The Band After Robbie’ or something like that. I looked at them when I first took them, the pictures they wanted, but, after that, there was no one asking to publish them. And I didn’t have a way of doing my own books like I do now, so if magazines weren’t interested, there was no revenue, so there’s no reason for me to go through the pictures again. Of course, I have new pictures I’m taking all the time that I want to look at. But your question has set something off in me that I really should think about. Maybe at some point I’ll have the luxury of having my assistant, Caitlin Allison, look at the later band pictures. ‘The Band after Robbie’, perhaps, or maybe ‘The Band Volume 3’. I’ll tell you, I have so many nice pictures. Really beautiful. If you go to my website, Elliott Landy and look at the photography, look at the flower visions and ‘kaleidescapes’. And I think that there’s one that may say ‘Oxana’. Those are mother and baby photographs, where I took the most gorgeous photographs of them.

I guess that leads me to where you are now and what you plan to do next? Given that you’re just about to put out a second volume of pictures of The Band you’re clearly not set on retirement anytime soon.

So, this is a book of photographs (holds up a book proof). It’s not a published book yet, but it’s a dummy book and it’s photographs of my wife of 23 years. They’re really nice photographs. And so, it’s a book of photographs of her and then texts that she’s written. We first met each other in college in 1962 and didn’t see each other for 37 years. Then we re-met. And when we re-met it was like, okay, we both knew we were going to be together, that kind of thing. So, her text for the book is to support women of a certain age, not to be afraid to change their lives if something comes along, and just go for it. In other words, to encourage women not to be afraid to change their lives. But I did it as a photographic book to start with. The book has been ready for a while and I tried to find publishers and couldn’t find a publisher. I’ll probably do a Kickstarter for it. Great photos, great. What’s it called? ‘Love @ 60’. Then last summer in France, I took maybe 4,000 photographs and discovered this kind of new form, a new way of making photographs look like paintings. This is street photography. I call this 21st Century Street photography. You walk out on the street to see what kind of beautiful things you can find to show people. So here I’m using a digital camera with a digital filter inside it. This is how the pictures come out. I don’t Photoshop things at all. I take the picture and that’s what it looks like, period.

Do you find one of the problems of getting your other projects out there is that people bracket you, that they only see you as a music photographer?

The reason why people think I’m a rock photographer is that’s all they look at. But then that’s all the media has presented over the years. I’ve seen so many publishers about ‘Love @ 60’ for example, or our European trip when I left the U.S back in the ’70s, I call it ‘In the looking is the finding’. We left the states with literally $22 in my pocket on the airplane with our year-old baby and our dog. I expected people to send me money that they owed me in the States, and no one sent us anything. So we really were starting with zero money. And it’s such a fabulous story of helping and being helped. The story is that I couldn’t find a publisher for that book. And I’m still trying. I’m going to get back to it at some point. And because it’s a lifetime story, not about one thing that happens, about how if you put yourself out there, then the universe comes and helps you. The world comes, people come and help you, and later on, then you help the same people. It’s all true stuff. Which is what makes that book so great. So, I got a lot of stuff to do yet.

We probably ought to be wrapping this up. Just in terms of the new book; when do you hope that will come out?

Well, I hope it’ll come out by November. Realistically. I’m not sure it will, but I’m sure going to try and get it out that quickly because until it does come out, I won’t be able to think of anything else. Well, I mean, not as exaggerated as that, but it’ll always be with me. I’ll wake up in the morning thinking about it and go to sleep at night thinking about it. So I hope it’ll come out in November and then I can move on to the next thing. What I’m looking for, if someone, universe willing, is seeing this – I don’t have a distributor for the book. What I do is that I contract with the printer and I finish the book. I get the book printed and I find the right printer and get it technically correct and everything like that. And then I need a book distributor to sell it to bookshops, to sell it online, to sell on Amazon to deal with the shipping and all that stuff. Basically, I package the book and they then publish it as their own book. They put their imprint on it and so on. So I’m looking for that. I’m looking for a publisher for Worldwide, but one that will take it the way I do it; I’ll be doing it my way. And I got that with the last Band book but we haven’t gotten that far yet. So I’m open to offers folks!

Well, hopefully, someone will see this and step in. The chance to distribute the next book of The Band photographs sounds like too good an opportunity to pass up. Elliot, thanks very much for your time. It’s been a real pleasure to talk to you. I’ve really enjoyed it.

Thank you man. Me too. My pleasure. Bye