Frank Turner describes his journey along the road to his 3000th solo show.

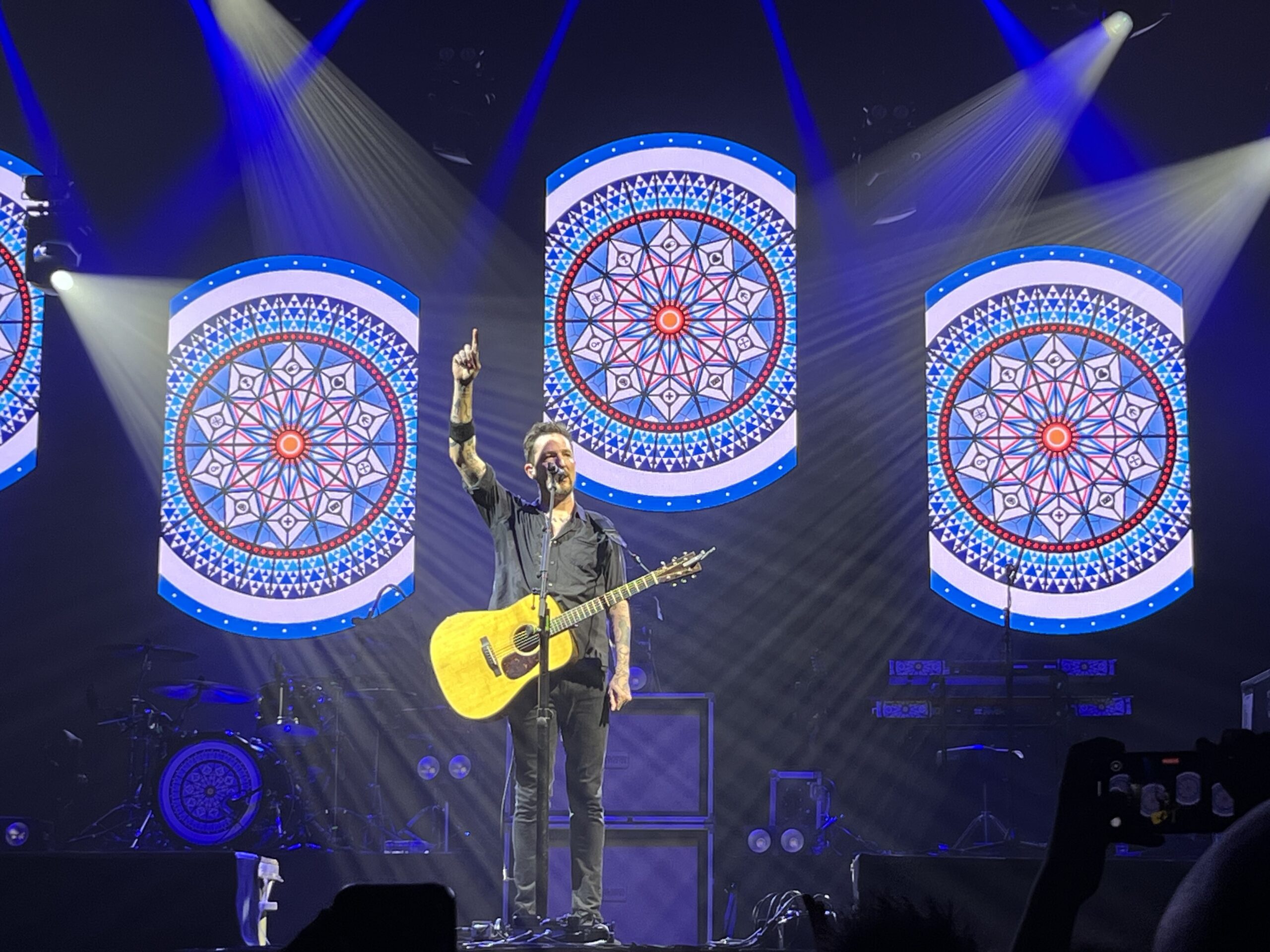

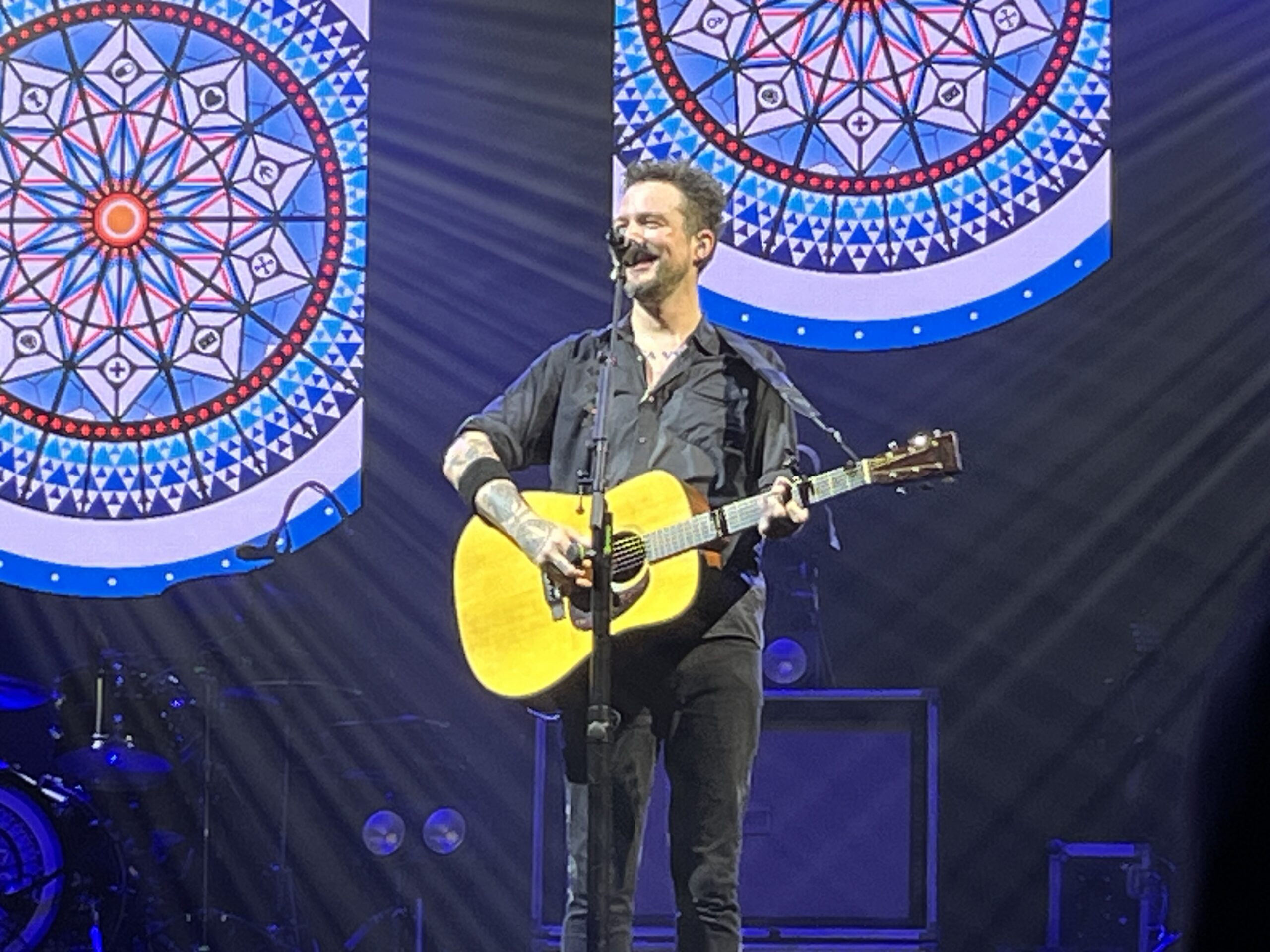

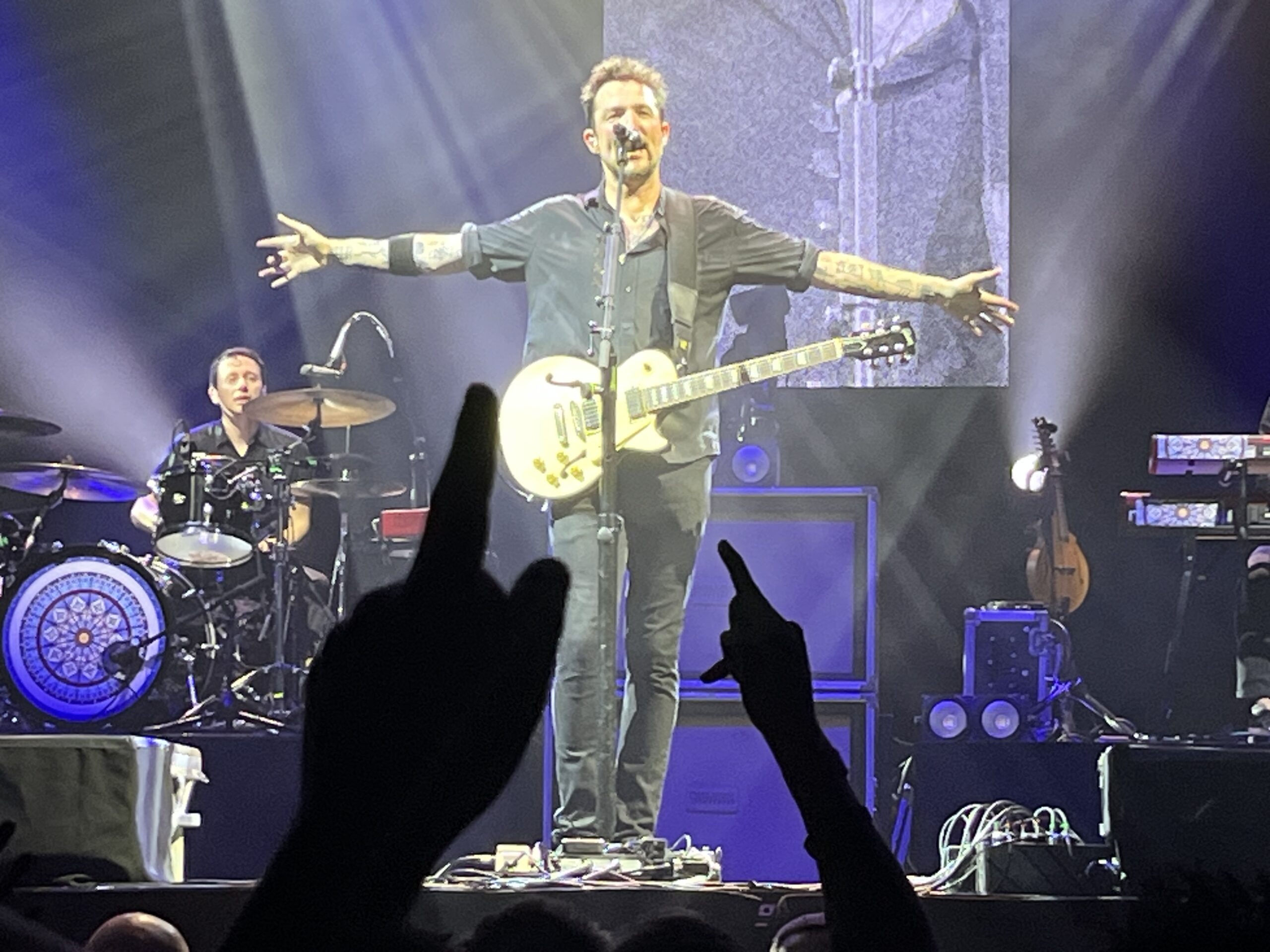

When I woke up on Sunday 23rd February 2025, my body felt absolutely battered. My ears were ringing. My head was pounding. My joints were aching. My muscles were cramping and I would not be able to walk without discomfort for the following week. But for all that physical fatigue, I was elated. The night before, over 10,000 avid Frank Turner fans had celebrated his 3000th solo show at London’s Alexandra Palace and I was feeling the effects of spending the entire gig front and centre, alternating between the crush and the mosh pit. The camaraderie in the crowd was joyous and, for those lucky enough to get tickets to this sold-out gig, it was a euphoric occasion that will remain long in the memory. Turner played 25 songs drawn from across his career, including old favourites and newer songs, barnstorming anthems with The Sleeping Souls and stripped-back solo acoustic songs. 3000 shows – it’s an incredible milestone, resulting from a relentless, non-stop touring lifestyle and a cult connection with a fan-base hungry for his energetic performances. Over the years, there have been some memorable moments, from appearing at the 2012 Olympic opening ceremony to playing at the Houses of Parliament. He’s done everything from headlining Wembley Arena to performing in car parks, achieving a Guinness World Record along the way. AUK’s Andrew Frolish had the opportunity to catch up with Turner a few days before Show 3000, to mark this remarkable achievement and to gain an insight into his life on the road.

With Show 3000 coming up, I thought it would be really interesting to focus on the touring life and what it’s been like on the road. I thought I’d start by taking us all the way back in time, all the way back to your final show with Million Dead back in September 2005. What do you remember of that show and your feelings about the uncertainty afterwards?

I mean, speaking candidly, that was a pretty messy time in my life. I’m glad to say I’ve come out the other side of a drug problem in my life, but it was sort of incipient at the time and I was very unhappy about the fact the band was ending; I did not want the band to end. So, I was pretty messed up on that whole tour and, by the end of it, I was in a bit of a state. I remember being very physically incoherent. I wasn’t sleeping or eating much and all that kind of thing. I remember the sound check being utterly depressing because I knew it was our last sound check and I didn’t want it to be our last sound check, so was pissed off about that. The tour had sort of held together because there was always one more show, if you know what I mean, so every day, at least there was tomorrow. That show, specifically, when there was only one more to go, a lot of the wheels fell off, emotionally and physically, and also just in terms of inter-band relations. You know, no one was even sort of pretending to like each other anymore at that point. So, it wasn’t the happiest day in my life. I remember the show being good, except that they had just refurbished the venue and it was insanely hot. It was a very, very packed room and I remember you could barely breathe and I passed out because of that and because of the physical drug stuff earlier – I passed out, fully passed out on stage more than once during the show and another member of the band just sort of kicked me in the head to wake me up. That’s kind of how things were at that point. Yeah, not the most cheery day of my life but we got through the show and I remember, at the end, I walked off the front of the stage and just walked out the front of the venue and walked away. I went to a house party that some friends of mine were throwing and didn’t help pack up or load our gear or anything, which I am ashamed about these days. I’m pretty sure I didn’t see or speak to some members of the band for many years after that. So it was a pretty doom-laden occasion.

Of course, you were then going in a very different direction, deciding to go solo with just an acoustic guitar. What things influenced you at that time? Other artists, people who supported you?

A couple of things. My taste in music had started evolving. My journey through music was quite tough because my parents don’t listen to any kind of modern music. I discovered metal and then punk and then hardcore and I knew everything about Sick Of It All before I knew anything at all about Bob Dylan, you know? I always think about this: I knew the song “Bob Dylan Plays Propaganda Songs” by the Minutemen before I’d ever actually heard any Bob Dylan songs. So, there was a process of me educating myself because I knew that this was a little weird. I started listening to stuff like Johnny Cash’s American Recordings series, Springsteen’s “Nebraska” era and “Devils and Dust” and those kind of more acoustic, rootsy records, a lot of Neil Young, Ryan Adams, a guy called Josh Rouse, who’s an American singer-songwriter. I had this kind of slightly random collection of more acoustic-based artists that I was starting to get into and it was turning my head. I’d gone to a few shows like that, and really enjoyed them and enjoyed the different energy, you know? It’s different to a hardcore punk show. The other thing that’s worth mentioning is we did do a tour in 2004 where we were on the bill and Funeral For a Friend were headlining, but there was Jonah Matranga in the middle of the bill playing solo. Jonah had been in a band called Far, and then he did solo stuff and he was playing solo at, I’m not sure punk is quite the word for Funeral For a Friend, but let’s say emo show. It didn’t really occur to me until several years later but I think that turned my head a little bit, watching him do that every night and thinking that’s an interesting thing to be doing. The other the other thing to mention is I was really into Counting Crows since I was a kid thanks to my older sister, and I learned a lot of that songs on guitar because my sister didn’t want me to play Megadeth songs at a house party, so I played Counting Crows instead – that was kind of a string to my bow. Then, in 2004, what is listed as my show 1 was the first solo acoustic show I did under my name; it was a charity all day event organised by a record level called Smalltown America at 93 Feet East in London. I played a solo set and it was a kind of a new thing for me at the time. I wasn’t sure whether it was a good idea or not. I’d taken to wearing a cowboy hat at the time which I am not super-stoked about in retrospect! I played a set of a handful of songs that I’d written and then a bunch of covers.

One other element that led to all of this was I’d started hanging out in a bar in North London called Nambucca that was run by a guy called Jay, who still makes music as Beans on Toast these days. It was kind of an indie bar. There were a lot of bands that were around the post-Strokes thing. The Holloways were formed at the bar. We used to go there, get fucked up and stay up all night and have lock-ins when Jay would play songs on his acoustic guitar. There were other people hanging around the scene at the time like Jamie T and Laura Marling and people like that. It just turned my head a bit again into the possibility of playing music with the acoustic guitar in a live setting, playing on my own .

Million Dead had agreed to go out with a tour, so I knew the end was coming and I’d started booking a handful of solo shows. After that last Million Dead show, which was horrible and doomy, I then went out pretty quickly on the train and, I think, I played Southend Chinnerys. I think that was show number 3, from memory. I just started booking solo shows just to see how that went.

What was it like being solo, on your own without a band, both performing on the stage and also the touring life?

There were pluses and minuses. At the time, my perception was that I had been let down. I might even have used the word ‘betrayed’ by the way things had fallen with Million Dead. I’m old enough now to recognise that I had as much responsibility for the breakdown and bad relations as anybody else, but at the time I felt like I couldn’t depend on anybody else. So, the fact of being my own was quite liberating and I enjoyed that. The actual fact of being on stage was terrifying because when you’re used to playing in a loud punk band or hardcore band or however you want to describe Million Dead, it was quite weird. It was quite naked. You can’t just sort of go into a noise solo and blame the drummer when you fuck up! A lot of this was intentional. I was very attracted to the idea of playing solo because then it’s just a good song or bad song; you can’t just say, well, the drums are good or whatever. I liked that, and the fact that it was miles out of my comfort zone was part of the attraction for me. You know, I wanted to set myself challenged to do something different. I don’t know if I thought that it would go anywhere at the time. I was a little sceptical. A lot of other people were a lot more sceptical. A lot of my friends and particularly industry people who Million Dead had worked with thought I was having some kind of psychotic episode at the time. It’s funny in retrospect! Everyone at the time thought I was nuts and I thought I had a plan. Now, looking back, everybody thinks I must have had a plan and I think I must have been nuts! I guess the thing about that period of my life is that in some ways it’s quite unrecognisable for me. I find it difficult to associate with that person. I mean, that is an issue I have in general – that association with my past. That’s a whole different conversation. But it feels like I’m remembering watching a film about somebody else when I think about that time. But I am proud of that guy because it’s unquestionable that it was me following my art. There are some people who think that I started playing this kind of music because it would be more commercially successful. In point of fact, that’s not true – I would have had a much easier time if I had formed another band that sounded like Million Dead because there were reasons those kind of bands were riding high at the time. Instead, I chose an unpopular, unfashionable root through music and the only real reason that I can think of for doing that was that I thought that it was the art that I wanted to make and there’s something quite pure about that that I’m quite proud of.

What were the venues like on the circuit around that time in those early days? What do you remember about the places and the people?

Well, the first thing to say is that I had a leg up because of my group. I remember the first time I played a show when I didn’t have ex-Million Dead written in brackets under my name and I was really stoked. But, of course, the associations with the band were helpful because we were medium-successful; we could sell five hundred tickets in most cities in the UK. That association got me gigs – not the same size gigs, it’s worth saying, but gigs nonetheless. I played some of the places Million Dead played. I was able to play smaller places because it was just me and my guitar; there were lot of independent venues, grassroots venues is the term these days – no one said that then! A lot of back rooms of pubs. I remember playing a show in, I think it was called Silks in Bournemouth, which didn’t even it didn’t have a stage and I’m not even sure it had a PA and I just stood in the corner and and yelled for like an hour or whatever! A big part of the reason that a lot of my early songs are quite vocally forceful is because I was used to trying to get people’s attention! I had to make noise to be noticed! It was the underground, DIY, independent music circuit.

Very different now! You went on a journey from those sort of house gigs and rooms in pubs to headlining Wembley Arena. How would you sum up that journey and what did you learn along the way?

It’s the most formative period of my life, really. I wrote a book about that specific journey from show 1 to Wembley, which was show 1300 or something. At the time of writing it, it seemed like a lifetime. When I think about it now, it was seven years, which as a 43 year old doesn’t actually feel like all that long, you know. It was a steady progress. It was kind of funny – a lot of my friends from the Nambucca-scene got signed and got enormous on their first records, like Jamie T being a good example. There’s no disrespect to me saying that – I think he’s a genius and he should be huge, but that didn’t happen for me. There were quite a few moments where I would sort of be standing next to somebody and they would get raptured. Do you know what I mean? They would just go ‘whoosh’ and be enormously famous and successful and I wasn’t. There were moments in time when I found that quite annoying and quite disheartening but, in retrospect, I think it was valuable because I earned my fan-base slowly, person by person, and it meant that there’s more longevity to it. By contrast, I have had friends who got very famous very quickly and then they got very unfamous very quickly as well. You know, they got kind of dumped, as it were, by the general public. So, I learned a lot about persistence and perseverance and self-belief. I learned a lot about songwriting and music and performance. I put a band together, The Sleeping Souls – they came together at that time. I learned many things and I saw a lot of the world because I started in the UK and I spread out to Europe. In 2007, I believe, I went to America on tour for the first time. It was like concentric circles that got bigger and bigger as time went by.

You mentioned The Sleeping Souls. How did that evolve and how did the addition of a band again change things?

Well, I always wanted to have other instruments on my records. I mean, there’s this weird kind of false memory going around that my early records were solo, which just isn’t true and I didn’t want it to be true. But the touring was because I couldn’t afford to take a band with me and I didn’t have a band at the beginning. In the very beginning, I was using programmed drums and stuff. I don’t think Logic even existed and can’t remember what program I was using for that. But, yeah, I wanted to play with people. Right at the beginning, towards the end of Million Dead and in-between tours, I was crewing for a band called Reuben, doing the merch. They had a support band called Dive Dive that featured Nigel Powell, Ben Lloyd and Tarrant Anderson. So, I’d met them and told them I was thinking about doing this other thing and they had a recording studio set up Tarrant’s house. They said if you ever need somebody to record your stuff and even play on it because we’re musicians, then we could do that. So the first solo EP, “Campfire Punkrock”, we did like that. The first album we did like that. So, those guys – Nigel, Ben and Tarrant – were around from day one, but tangential to the project for a while. We played our first full band show in 2007, I believe, and we had a series of rotating keyboard players. We had Jamie from Dive Dive for a while, who doesn’t play keys! Then we had Ciara Haidar, who was great, but left to play keys for The Kooks, I believe, and now writes K-pop songs and was well last time I saw her. Then we had Chris T-T playing keys in the band for about a year, and then we found Matt Nasir. That was the line-up for a while, then Nigel left and we got Callum in in 2020.

Obviously, writing songs for a sort of hypothetical band and writing songs for an actual band is quite different, both in terms of what’s going on in my head, but also actually working out parts and arrangements and stuff before you record rather than afterwards. So, they’ve definitely become a much more integral part of the sound and the style of what I do as time has gone by.

And, of course, big part of the shows now. We see those energetic shows, a couple of hours of this high-energy, party feeling, but there must be a lot of work that goes on behind the scenes. Tell us a little bit about what that’s like, the behind-the-scenes work that goes into it.

The first thing to say is that I probably do less behind-the-scenes work than most! For obvious reasons, people ask about The Sleeping Souls more often than the crew, but the crew are just as much a part of it, in my mind. I’ve had the same core crew for years and years now, and they’re as much family as anybody else. They work their arses off making the show happen and catering to my whims and making sure I’m in the right place and talking to the right people, reminding me that I had this interview, for example, and things like that! So, you know, they do a fantastic job. I mean, it’s funny, with what I do, the public facing part of my day in the two hours on stage, some people seem to think that’s all I do with my day, which is very much not the case. There are other things that get done as well: promotion, logistics, sound check, dealing with technical issues, whatever it might be. So, there is a lot that goes on behind the scenes that people don’t see, but I don’t have a problem with that. I mean, that’s the nature of the beast – we’re presenting something to the audience. There’s a lot that goes on. Keeping the show on the road is work. Keeping 13 people in sanity and food and shelter in different places every single day is an awful lot of work.

Do you have a routine on the day of a show, habits or preparation that you sort of religiously stick to?

Yeah, I do. A lot of it’s practical, but it has assumed a kind of more mystical veneer, shall we say as time has gone by. I see my voice for half an hour. I do my vocal warm-ups for half an hour. I do my physical stretching for about 45 minutes. I do the same thing every day in all of those three, and I find that very centring, you know, because that’s the thing I do before I play – it makes my mind and my body start getting ready for a show. The other night we were in Dublin and my warm routine takes just under two hours. Just before I started doing it, I was like, ‘I can’t fucking believe I’m supposed to be playing shows today – I’m completely in the wrong head-space.’ And then I started doing it and, by the time I finished, I was raring to go and we had a great show apart from the bit where I injured myself at the end, but that’s a whole other story!

There are final checks before we go on and we all high five before we go on. We talk through the set-list. There are things we do every day that have become our tour routine and I find a lot of comfort in that because we’re in a different place every day and because things can be quite chaotic and not very comfortable. The fact of having a series of routine things that you do every day is is comforting, for sure.

It must be difficult, particularly in the gaps between the things that you have to do. So, what do you do that keeps you sane along the way?

I read it a lot. A lot! I’m definitely a bibliophile, reading and collecting books. I’m currently reading a history of the reign of Henry VII, you’ll be ecstatic to hear! I tend to have breakfast on my own in the mornings. I take myself away and find a cafe or something and just have an hour or so with my book to gather myself a little bit. A lot of my day is very gregarious – that would be a polite way to put it. It’s very social and there’s people to talk to all day, every day. So, having a bit of time where I don’t have to talk to anybody is something I find very restorative. Reading’s a big part of it but I write while I’m on tour as well, not in a regulated way, but ideas arrive and I try to carve out time to do something about them. I’m in my dressing now and I have a guitar next to me should the moment strike.

It’s a relentless lifestyle.

It’s worth saying that there’s a fair amount of machismo and bravado around touring as a general rule, you know. ‘Can you hack it?’ kind of vibes. I have mixed feelings about that. I’ve definitely been guilty of indulging in that mindset at times and it is hard being on tour all the time; there are some people who cannot handle it at all. The first tour I ever went on was when I was 16 years old – about 12 of us went and about six people came back being like, ‘I will never ever do that again – that was awful.’ The other six were like, ‘When do we go again? I want to go now!’ I was in the second camp as you might imagine! But yeah, some people are much more kind of home-bound, creature comfort-bound, routine-bound, whatever it might be. I get that. There’s nothing wrong with that; there’s nothing to be ashamed of in that. It can be physically and mentally challenging on tour, for sure.

You literally took the words out of my mouth. I was about to ask if it’s tough physically and mentally? Or do you actually find it the opposite – that it’s revitalising and energising, it’s your life-blood?

I would say it’s both. I mean, the important thing to say is that this is my life. I mean, I’ve done this since I was 16 years old. This isn’t like a holiday from some other life that I’m going back to once the tour is done – this is what I do. I’m used to it and in some ways in the last ten years I’ve found being off tour harder than being on tour. In the lock-downs, that whole period of time was quite challenging because I was without my usual physical and mental outlets and my routine and all that kind of thing in the world that I’m used to. I made my peace with it in time, but it was a challenge in places. But this is what I do. It can be tough. The physical thing gets harder as time goes by, for sure. Like I say, two nights ago in Dublin, I injured my ankle quite badly at one stage. As a friend of mine said when I was texting him about it, we’re now at an age where we don’t bounce, we just crunch, which I think is true. I look back now at the early tours with The Sleeping Souls and there was one tour when we did something like 28 shows in a row without a day off, which now strikes me as completely insane. I just couldn’t do it now. I couldn’t. We do play for longer than we used to, but it’s not just that. It’s that the human body slows down we get older and certain things start to hurt more and you need to be more careful about your diet and your sleep and all that kind of thing. We certainly, in quotes, party less than we used to. There was definitely more of that back in the day. I can’t get hammered every night – it’s just not an option; my body can’t do it. In particular, my voice can’t do it. I spend an inordinate amount of my day thinking about my voice, seeing what shape it’s in and how much warming up I have to do and whether we have a problem for the show and all that kind of stuff. So, it does all add up and it does get physically taxing, for sure.

Although you did manage a Guinness world record last year, of course – the most shows in 24 hours. What was that like?

It sucked – it really sucked! I mean, it was fun and we raised money and awareness for independent venues and I got a world record and we promoted my new album and all those good things that we set out to do. And I knew it was going to suck to a degree. It was harder than I thought it was going to be and the day afterwards I could barely speak. In terms of my voice, I could barely make a fucking noise! We played 16 shows, I think it was, in 24 hours and that was pretty cool. The last third of it was horrible! Horrendous. At the start of it, my crew said two things to me: first of all, this was your fucking idea so don’t go trying to blame this on somebody else and, secondly, we’re never doing this again. This is a one-shot thing. If somebody else tackles that record and beats my record, I will meet them at the finish line with a silver blanket and a mug of tea!

That was one unusual touring event amongst many. You’ve done some amazing things, from the Olympics to the Houses of Parliament. Are there any really unusual shows or events that stick in your mind that you can tell us about?

Those are two. The 50 states in 50 days thing we did in the United States was hard as well. It was hard in a slightly different way. It was a more prolonged type of suckingness! Actually, the back end of that was alright; the middle bit that got really, really grim for a while but, you know, we did it, tick – it’s on the CV! I’ve got a bit of a rep for these stunt ideas for shows. That’s fine, whatever. They’re fine but they’re challenging. Quite often, my crew are just like, ‘Can we just do a fucking normal tour?’ Obviously, the Olympics opening ceremony sticks out. I’ve played a fair few shows now in Sierra Leone. I work with a charity out there called Way Out Arts and I have played some very, very odd shows as part of that, and they definitely in the memory. Probably the weirdest show I played was in a car park by the side of the road in East Freetown. I was standing on a bunch of soap crates and playing through a reggae PA, which didn’t really have any tops, and playing to an audience of about 300 heavily-armed Sierra Leonean gangsters. That was quite odd. That made me feel very white and middle class! It was amazing. It was life-affirming and I have friends out there that I value dearly and I hope that I’ve made some sort of difference with the charity fundraising angle of that as well. That definitely sounds out!

That sounds amazing – what an experience. And all these experiences, from those early days touring on your own through to Sierra Leone via the Olympics, brings us to Show 3000. What does it mean to get to a milestone like that?

Well, arguably not much you could say! It’s funny – I started counting shows at the beginning because Ben who was the drummer of Million Dead started counting shows. At the time, I thought he was a bit weird for doing it but, by the time band broke up, I was grateful that he had because then I had a record of what we did. Even in 2005, I was starting to forget some of the details of where we’d been and what we’d done. So I was happy that he kept that list. So, I started keeping a list of solo shows, and put it up on my website from day one. When we got to show 1000, I got some friends of mine to organise a gig in a car park at Shoreditch and we had about a thousand people. I got paid in drugs. It was a benefit show for the Joe Strummer Foundation and we raised a lot of money but it was funny because when I was organising it, even on the day, I remember showing up and saying, ‘Show 1000!’ and everyone’s saying, ‘One thousand what? How do you even know that?’ and I showed them the list. Even though it was marketed as a thousand shows, I’m not sure anyone really paid very much attention or cared. By the time we got to show 2000, people did care and that was a big deal and we did a live album for that one.

Now we’re at 3000 and it’s been wild. We booked Alexandra Palace, a venue that I love. It’s a big room that holds 10,500 people and various people in my organisation were a little sceptical about whether we would sell it out or not. We thought maybe we’ll get some 9,000 tickets on the day and we’ll call it sold out. Then we sold them all in 24 hours, which was shocking even to me as the optimist in the conversation. I’m very proud of that and I’m very blown away by that. I’m very grateful for that. Quantity does not equal quality. There’s no specific reason why show 3000 should be better than the show 2999 but it’s an excuse for a knees up and for a big gig and everything. We’ve got people coming from all over the world and that kind of thing, which is awesome, and I am excited about it. I do this quite often – I only really started thinking about the actual reality of the fact that we were playing that show about three days ago. I was just like, fuck! My crew, on the other hand, have been working on the logistics of it for about six months and they’re just like, ‘Welcome aboard, dickhead!’ We have some bells and whistles; we have some friends coming down and family, so it’s going to be a big deal. I’m excited for it.

I’m excited too! How on earth do you go about choosing a set list for a show like that?

I’ve been thinking about the set-list for a while and it is almost there! I have things I want to achieve and showcase, so I spend an awful lot of time thinking about this. I want to represent every record that I’ve done in every era of what I do. I want to make a cool set for a live album once it’s done. I want people in the audience to enjoy themselves. I want everybody to enjoy themselves and to feel included, but I also have messages that I wish to convey and all that kind of thing. I’ve had nine million people making requests and I’ve basically ignored them all for this particular show. I usually do take requests but, in this instance, I’m going to pick the set-list for this particular show! Hopefully, people will enjoy it. There’s still one question mark at the moment and we’re hoping to work it out tonight in Wolverhampton.

It’s obviously been a long, long road – this touring life. If you had not travelled down this road, where do you think you’d be now? I guess the ‘Somewhere Inbetween’ video gave us a hint, maybe?

Yeah, definitely. My mum’s teacher and I flourished in the academic world. I did a degree and enjoyed it. I don’t want to be quite so flippant to say, oh, I’d be a teacher as if being a teacher is a simple and easy thing to be because I don’t think it is. I think that I would probably be trying to be in that world doing something to do with history because that is my other major passion in life. But I think I’d probably still be involved in music somehow, somewhere. I don’t quite know what that would look like if it didn’t look like this. Counterfactuals! Who knows? I’m very grateful things worked out how they are. I think that you could waste a lot of time thinking about what ifs and different roads but, ultimately, I make a living playing music, and that’s a huge privilege that I wouldn’t swap for anything. So, I’m not unhappy about how it’s panned out.

It’s panned out pretty well! One final question, and this is a more general question. What about a word on the future of the live music industry in the UK and beyond and what do you see this life looking like in a few years, not just for yourself, but for new acts coming through?

This is the problem. I think those are two separate questions. I do think that I worry about how engaged with live music as a concept younger generations are, particularly after the pandemic and lock-downs. Also, I think about the enormous damage done to all of us by social media, which I think is the very devil. And that’s all of it, by the way, not just some of it, but all of it. Like most people, I’m hoping for some sort of renaissance of interest in live music, but it’s definitely the case, I think, that people my age are more acclimatised to live music as a concept than younger people are. It’s interesting – if you go back and look through all the old issues of ‘Kerrang’ from the early ’90s, live music was a much smaller affair even then; fewer people went to shows. It was a much more specialist interest. Nirvana was the biggest band in the world in 1992 and they played Brixton Academy. If they were the biggest band in the world now, they’d be doing five nights at the O2 or something. I remember Rage Against the Machine played The Astoria when they had a number 1 album. So, these things do come in waves. I hope that it remains healthier or remains a thing that people are interested in because it’s not just my living, it’s my passion. Live music is my favourite thing in the world. But it’s not really for me to dictate that either. All I can really do to contribute is to keep doing what I do, which is the plan.

It’s a good plan. I do think you’re right – it is cyclical. I think we’ve been through a real golden period for live music. Perhaps it feels like it’s more important because artists are struggling with other revenue streams in a way they didn’t in the past because of streaming.

I think that’s definitely true. Even right now, making a living out of touring is getting harder. People talk about ticket prices going up, but a lot of the time, particularly in the States you find that parking spaces cost more than the gig ticket. Thanks for that! This inanimate square of concrete is apparently more valuable than what the musician’s doing on stage. There are small things at the edges that someone like me can work on, but the broad direction of culture, I think is beyond my remit!

Very interesting interview. He’s a canny operator (I mean this in an admiring way) who knows how to put on a “show” (again meant admiringly).

One small gripe. We’re off to see him in a couple of weeks, standing downstairs at Cambridge Corn Exchange. Now, people on the rail, yes. Mosh pits, yes. Crowd surfing, yes. But circle pits, please, no. I can choose to distance myself away from moshing and crowd surfing, but circle pits can come your way without warning.